Public sector pay settlements can often be difficult to digest, and this year’s NHS pay deal is no different. Yet the context of this year’s settlement – with a general cost-of-living crisis and rising wage competition from the private sector – means it is perhaps more important than it has ever been.

With strike ballots pending, it is too early to tell what the immediate, let alone medium-term, effect will be. That said, our analysis suggests there are some striking implications. For instance, it will if anything accentuate our already large pay differences between some professions. Also, while pay progression to reflect years in service means that average salaries of existing staff will increase above the headline settlement, it will still typically be a real-terms cut. We discuss these and other insights below.

What is the pay settlement for 2022/23?

First, a recap on what has been agreed. The government accepted the recommendations of the independent NHS pay review bodies in full. Starting with doctors, this meant that for 2022/23, hospital consultants get a 4.5% uplift to their pay framework (up to £5,130 in basic pay annually), as do salaried GPs. Some were absent from the pay review bodies recommendations, with the majority of doctors-in-training covered in an existing deal worth 2% – as little as an additional £576 a year – which they will argue was agreed in a very different economic landscape.

For the majority of the 1.2 million hospital and community staff employed on the NHS terms and conditions of service (Agenda for Change), there was a flat-rate annual increase of £1,400. The exceptions to this being the lowest pay band, which retains an additional £324 living wage uplift, and a handful of pay levels where the increases were between £161 and £434 above the flat-rate (equivalent to 4%).

What are the implications for different staff groups?

Analysis of disparities in pay between groups is complex and typically seeks to measure between groups doing the same work. But at a crude level it is perhaps striking that, for example, the absolute increase to basic pay for consultants (up to £5,130) will be far greater than that for nurses (up to £1,834) and clinical support workers (up to £1,724). These latter groups have more female and more Black and Black British representation. Given the review bodies’ remits include taking account of the legal obligations on the NHS, including anti-discrimination legislation, it is important to be mindful of the risk of the pay settlements contributing to direct or indirect discrimination.

The risk of accentuating pay differences between staff groups is also potentially problematic given the intention for these different staff groups to increasingly work together in multidisciplinary teams. Across the Agenda for Change contract – which covers the majority of staff – the effect of the pay deal will be to close the relative difference between the highest and lowest, given the flat rate of £1,400 extra represents a larger proportional increase for the lowest paid (up to 9.3%) than those at the very top (1.3%).

However, as already alluded to, this is not the case across the different contracts. In fact, the data suggest we already have one of the largest differences between fully qualified hospital doctor and nurse pay across developed countries health services.

Of the 26 countries with broadly comparable data, only South Korea reportedly has a higher difference in pay between the two professions (with salaried specialist doctors paid on average 3.7 times that of hospital nurses) than England (3.2 times), with the median across the countries far lower (2.3 times). While we don’t know exactly how average salaries will be affected in England, the disparity will likely increase in absolute terms (with basic pay of consultants increasing by between about £2,000 and £3,700 more than nurses) and do little if anything to decrease the gap in relative terms.

There are many reasons why these pay differentials between staff groups have developed. But without considering pay deals in the round, there is a risk that deals covering a smaller number of staff are more likely to receive increases as they may look more affordable in terms of overall cost implication.

How will the settlement affect the pay of existing staff?

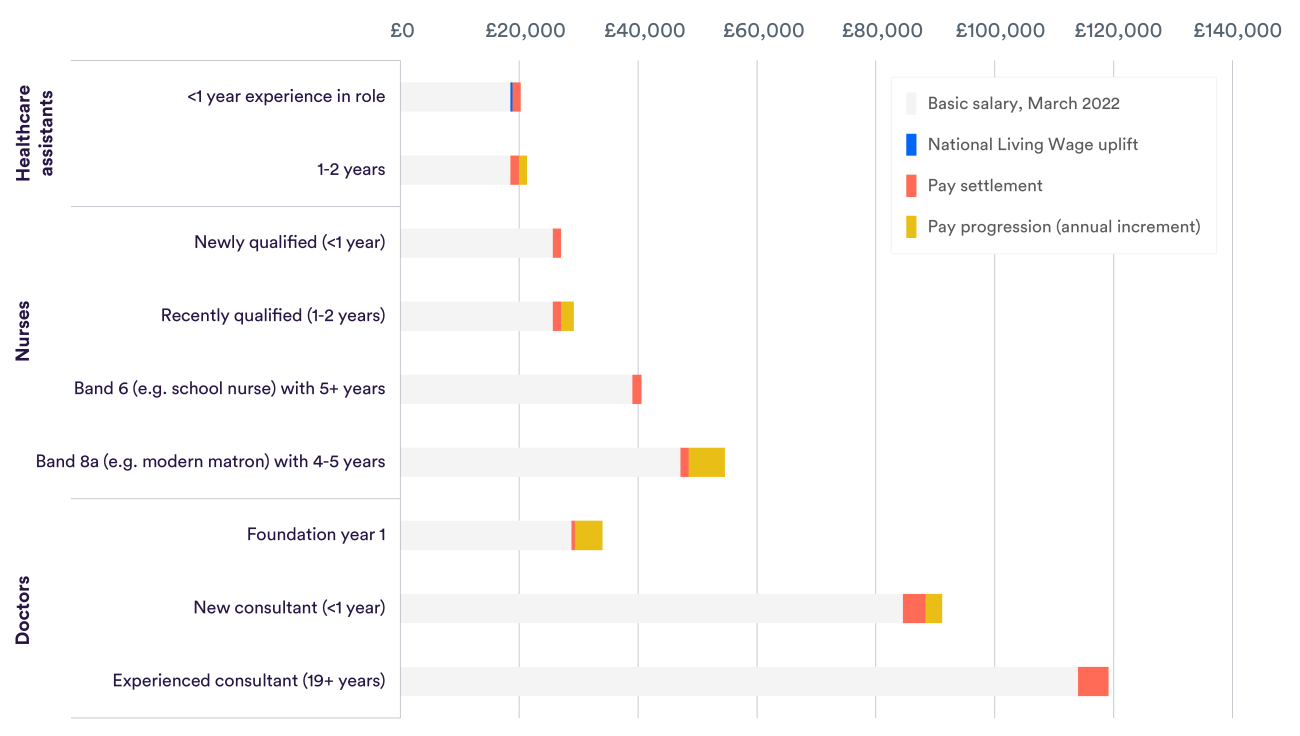

Particularly in the context of rising living costs, it is worth reflecting on how the pay settlement affects actual pay packets as opposed to the underlying pay frameworks. The figures above – as with those presented around the publication of the pay deal – do not account for the pay progression that some existing staff are due, to reflect their years of service. To demonstrate this, we have charted the likely change in basic pay for existing staff in selected groups, which shows pay progression can be substantial compared to the effect of the pay settlement.

Our own analysis using detailed workforce data from NHS Digital gives further insights for those employed on Agenda for Change. In particular, we found that only around one in seven staff on this contract (14% across all staff groups and 16% of nurses) are due an annual increment this year, which are worth between 5% and 17% (or £1,048 to £14,340).

Overall this means that, while the pay deal was equivalent to, on average, 5.2% for staff on Agenda for Change, factoring in these annual increments means that the basic pay of existing staff by March 2023 will likely be an estimated 6.4% higher than a year before. The figures are slightly lower for qualified nurses, with the pay deal worth 4.3% on average, which rises to 5.8% after accounting for annual pay increments. It’s also worth noting that these figures on the average percentage uplifts, even after considering pay progression (e.g. the 6.4% across Agenda for Change), are higher than the related cost to the public purse (5.8% across Agenda for Change), given the higher percentage increases are typically received by those on the lower salaries.

With spiralling costs – the UK’s annual inflation rate (CPI) stood at 10% in July – even accounting for pay progression, existing staff will on average be worse off this year.

What else?

Some of the adjustments are curious. In particular, for the 121,000 of those with at least five years’ experience at Band 6 (which includes long-standing school nurses and experienced paramedics), getting the higher 4% being offered – as opposed to £1,400 – is only worth an extra £161 annually pro rata, pre-tax. The intention of having higher increases is presumably to help retain some of the NHS most experienced staff, given that no staff with more than five years’ experience at their current pay band benefit from further pay progression. But, at around 43p a working day in additional take-home pay, it is not clear at all whether such an amount is in any way sufficient.

It is clear that the implications of the pay deal are complex. Publishing a pay deal 110 days after it should come into effect and just two days before the House of Commons rose for their summer holidays is not helpful in this regard, even if the pay increases are backdated to April. In fact, others have noted how the pay review process could be improved. While pay may not be the only way in which the workforce can be valued, it is important – particularly with rising living costs – and staff deserve a transparent and fair agreement, as do the public as taxpayers and service users.