Overview

- Although people in prison are deprived of their liberty, their right to health care is unaffected. But prisoners tend to be of poorer health than the general population and have complex health care needs.

- Addressing inequalities between people in prison and the general population is a key policy goal, but there are challenges to making this work in practice. Prisons are overcrowded, they face particular challenges with staffing and funding has decreased since 2010. Security concerns can also have a profound impact on how health care is delivered in prisons.

- Since 2013, prison health care has primarily been the responsibility of NHS England, which directly commissions primary, hospital and public health services for people in prison. However, from April 2022, prison health care commissioning could in theory become the responsibility of integrated care systems.

- All prisons have some health care services (such as primary care and mental health support) on-site and some also have dedicated health care wings where people can go to receive care and treatment. The exact set-up depends on the characteristics of the prison itself; there is wide variation in the services available across the prison estate.

- On arrival at prison, people should receive a health care assessment. During their stay, they should be able to access primary care services, and if they need to attend an appointment off-site, at least two escorts will need to accompany them. People in prison should also get access to the same public health programmes as the general population.

- But there are concerns about prisoners’ access to and quality of health care. The Covid-19 pandemic has also had an impact on this and current evidence suggests there has been wide variation in people’s experiences.

Key figures1.

- There are 117 prisons in England and Wales. As of 2019, around 4% of the prison population were female. 2

- The proportion of people in prison aged over 50 increased from 7% in 2002 to 17% in March 2020. Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) uses age 50 to describe ‘old age’ in prisons, given the significant health needs of people in prison. 3 Of the people in prison, 27% identify as minority ethnic, compared with 13% in the general population. 4

- The average age of death of people dying in prison is 56, compared with 81 in the general population. 5

- As of 31 August 2021, 18,442 prisoners or children in custody have tested positive for Covid-19 since the start of the pandemic and 223 prisoners, children in custody and supervised individuals have died within 28 days of testing positive or where there was a clinical assessment that Covid-19 was a contributory factor in their death. 6

Context

Prison health care is based on the principle of equivalence. 7 The Royal College of General Practitioners has published a position statement 8 setting out what this means for all secure settings in terms of the delivery of services. Meanwhile, HM Government and NHS England 9 have set out what equivalence means at a strategic level. The aim is to ensure:

… that people detained in prisons in England are afforded provision of and access to appropriate services or treatment (based on assessed population need and in line with current national or evidence-based guidelines) and that this is considered to be at least consistent in range and quality (availability, accessibility and acceptability) with that available to the wider community, in order to achieve equitable health outcomes and to reduce health inequalities between people in prison and in the wider community. 10

However, people in prison are one of the most deprived groups in society. For example, they are more likely to have been taken into care or have experienced abuse as a child, been homeless or in temporary accommodation, or been unemployed.11 People in prison also have significantly poorer health than the general population.12 Prison therefore provides an opportunity to address existing health care needs that may have gone unmet in the community.13

Addressing inequalities between people in prison and the general population, particularly regarding timely access to health care, is a policy ambition.14 But security concerns, difficulties with staff recruitment and retention, a lack of trained staff, overcrowding and an old-fashioned environment all represent distinct challenges to the delivery of health care in prison. As a result, the aim is not to provide exactly the same services as those in the community, but that equivalence reflects the need for health care in prison to be ‘at least’ consistent in range and quality with what is available in the community.15 In some cases, people in prison are provided with additional services, such as testing for blood-borne viruses.

Prison funding has fallen dramatically since 2010. The House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee, in its inquiry into prison health care16, highlighted the reduction in funding and consequent reduction in prison staff, which has had an impact on access to health care services and their quality. Analysis from the Institute for Government (2019)17 noted that only recent investment has begun to reverse this trend, with additional funding announced in 2016 and 2018 to improve prison safety and increase the number of prison officers.

This briefing provides an overview of what health care should be provided to people in prison. It does not go into detail on every service. What is available in practice varies between prisons. Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has also had an impact on prison health care, and current evidence suggests there has been wide variation in people’s access to and quality of health care. Even before the pandemic, there were concerns about prisoners’ access to health care services. But understanding the impact of the pandemic on the health of people in prison and health care services is essential to addressing the current and future health care needs of the prison population.

Key organisations, commissioning and regulation

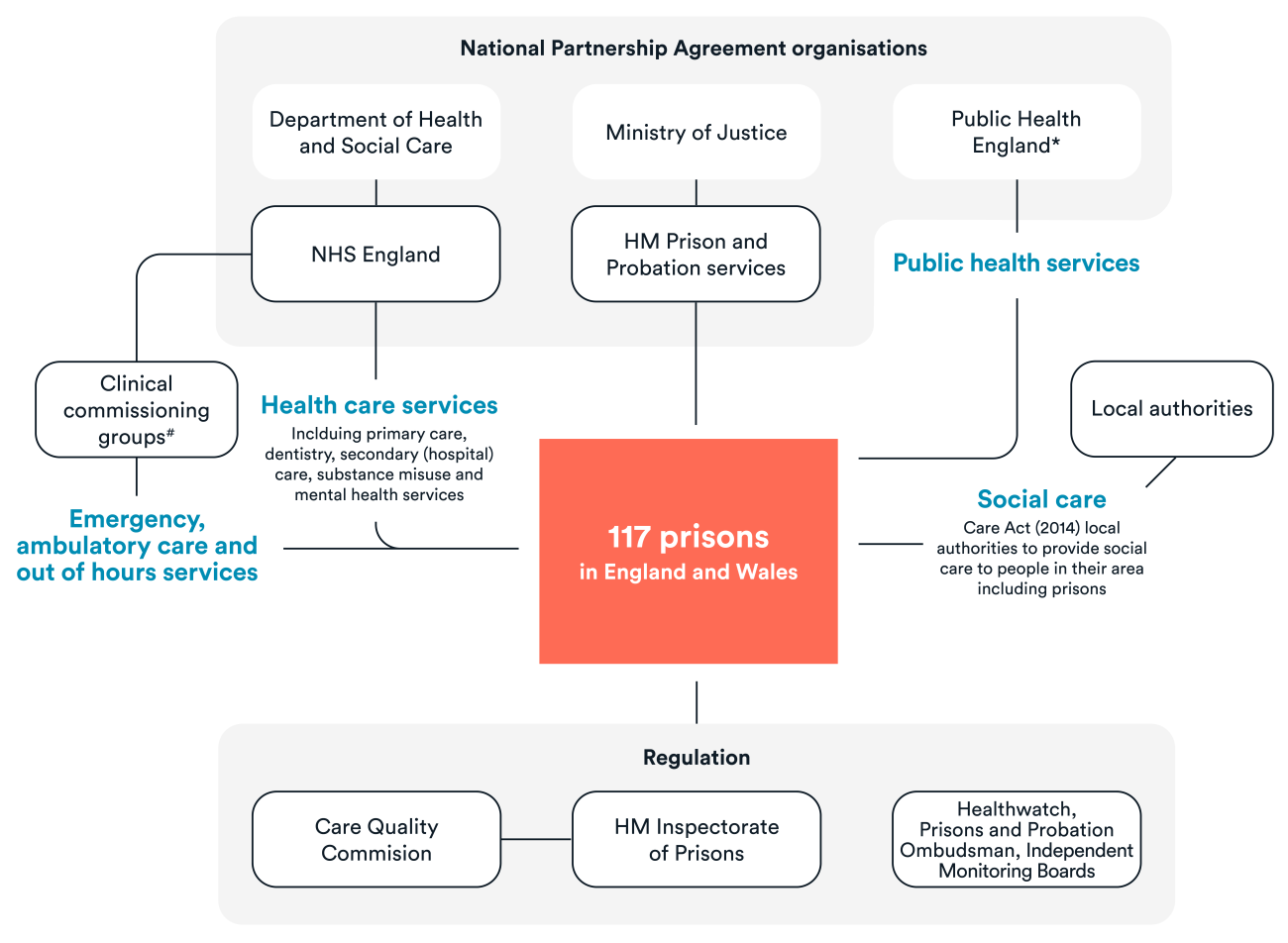

The Department of Health took over the responsibility of commissioning prison health care from the Prison Medical Service in 2006. Following the Health and Social Care Act 2012, responsibility for the direct commissioning of health care services in prison then transferred to NHS England in 2013. This includes primary and hospital care, public health and eye, dental and mental health services.18 The clinical commissioning group in which the prison is located, meanwhile, commissions emergency and ambulatory care and out-of-hours services. NHS England works closely with other government departments and arm’s-length bodies, including Public Health England and Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS).

The roles and responsibilities of these organisations are outlined in the National Partnership Agreement for Prison Healthcare in England 2018–2021.19 This also sets out the following three key strategic objectives:

- to improve the health and wellbeing of people in prison and reduce inequalities

- to reduce reoffending and support rehabilitation by addressing health-related drivers of offending behaviour

- to support access to and continuity of care through the prison estate, pre-custody and post-custody into the community.

The agreement signifies the importance of collaborative working between the organisations in order to improve prison health care in England.20 The National Prison Healthcare Board provides oversight of the agreement.

From April 2022, legislative changes will mean that commissioning health care services in prison could in theory become the responsibility of integrated care systems.21 Exactly what this may entail is still to be determined.

Our previous research into prisoners’ use of hospital care noted that the move away from the Prison Medical Service being responsible for prison health care is believed to have improved the quality of prison health care.22 In 2016, Public Health England conducted a rapid review, which aimed to understand how this move had affected it. It found that the consensus was that the move had resulted in significant improvements to quality of care through, among other factors, improved partnership working, professional development of the health care workforce and increased.23

The impact of the role of integrated care systems in commissioning on the quality of prison health care will be important to monitor, but it may provide an opportunity for services to more closely match the needs of the local population, and to be commissioned in a more integrated and collaborative way. There is a particular opportunity for this move to improve continuity of care when people are transferred from prison into the community.24 It will be important for integrated care systems to develop expertise in the health care needs of prisoners (both before and during their prison stay and on release), and the services they require.

Regulation

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) and HM Inspectorate of Prisons jointly inspect health care services in prisons.25 Since April 2015, the Care Quality Commission has also been responsible for inspecting adult social care services in prisons.26 HM Inspectorate of Prisons’ inspections are guided by the principle of ‘healthy establishments’, which includes a number of expectations concerning safety, respect and rehabilitation.27 The role of HM Inspectorate of Prisons in conducting regular inspections is important for fulfilling the UK’s obligation under the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT), which requires action to prevent the ill-treatment of people in prison.28

The key bodies, and commissioning and regulation responsibilities, are set out in the infographic below.

What health care services should be provided to people in prison?

Although there is guidance outlining the health care services that should be provided to people in prison29, in practice prisoners can experience challenges accessing health services and there is variation between prisons over what services are available.30 In this section we provide an overview of what services should look like and then, in the following section, we highlight some of the longstanding challenges surrounding access to and quality of health care.

All prisons have some health care services on-site and some also have dedicated health care wings where people can go to receive care and treatment.31 NHS England32 sets out the core services that should be provided in prisons and these should be evidence-based, person-centred and delivered by appropriately trained staff. However, the exact set-up should be tailored based on the characteristics of the prison itself and the needs of the particular prison population.33

On arrival

Within 24 hours of arriving in prison, people should receive an initial health care assessment from a health care professional to identify their immediate needs such as ongoing medication requirements for physical or mental health problems or treatment linked to drug or alcohol withdrawal.34 This should also include an assessment of any other medication needs, physical injuries and chronic health conditions (such as diabetes or asthma), as well as any recent medical appointments requiring follow-up.35 People in prison should also be screened for tuberculosis within 48 hours of arrival.36 Numerous templates exist to help with these assessments, including tools specific to identifying health needs in young people, such as the Comprehensive Health Assessment Tool (CHAT). From April 2021, prisoners should also be screened for brain injury sustained through domestic violence.37

A follow-up health care assessment should take place within seven days to address any issues raised at the initial screening that require ongoing input, as well as meeting more general health care needs and giving health promotion advice.38 People should be told how they can access ongoing medical support, such as how to book a GP appointment. This secondary assessment should also include screening for blood-borne viruses such as hepatitis C.39 Opt-out blood-borne virus testing was introduced in a pilot project in the prison estate in 2013, and it was rolled out across the whole adult estate in England in 2018.40

Information-sharing between prisons and the community

Collecting, storing and sharing data across services is a key commitment of the Digital, Data & Technology Strategy, recently published by HMPPS41, and the importance of data-sharing to support meeting the needs of people in prison is also noted in the overarching draft data strategy for health and social care.42 On arrival at prison and with their consent, the person’s medical records should be transferred from the community to the prison to ensure continuity of care.43 But historically, transferring records between prison and the community has been challenging. The Health and Justice Information Services is a national programme, commissioned by NHS England, which aims to bring the information technology (IT) system in place within the secure estate in line and up-to-date with other clinical systems used in the community.44 Successful implementation would enable sites to access the NHS national spine and services such as e-referrals and e-prescriptions. Patients will also be able to select the secure estate health care provider as their registered GP, enabling the electronic transfer of information between the prison and the community. The programme is intended to improve information-sharing between prisons and the community, including on the person’s release.

During prison stay

Primary care

People in prison should have access to primary care, as well as services such as dentistry, podiatry and ophthalmology. People can request to see a GP if they need to and some prisons have GPs on-site. Services should have staff from a range of disciplines, appropriate to the particular setting and prison population.45 At a minimum level, services are expected to:

- provide emergency (within two hours) and urgent (within one day) referrals

- provide an opportunity for people to book appointments up to 48 hours in advance

- have a system in place whereby people in prison can consult a GP where these are not available on-site.46

Secondary care

Some prisons may have access to diagnostic equipment such as portable fibro scanners, to assess liver cirrhosis, or dialysis machines. If someone needs to attend an appointment off-site (such as at a hospital), they require at least two escorts and may require restraint such as handcuffing, based on an individual risk assessment.47

Social care and end-of-life care

Through the Care Act 2014, social care remains the remit of local authorities and they are responsible for providing social care services to people in prison living within their area. People in prison who have a terminal illness may be eligible to apply for the compassionate early release scheme – the most common reason for early release is cancer.48

Public health

People in prison are entitled to access all appropriate cancer and non-cancer screening programmes for their age, sex and other risks factors, as well as the NHS Health Check programme.49 Eligibility for Health Checks in prisons starts at age 35 (as opposed to age 40 for the general population), recognising the higher prevalence of risk factors in the prison population.50 This is important given that cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for people in prison.51

It is estimated that around 80% of prisoners are smokers on arrival to prison52, compared with just under 15% of people in the general population.53 The extent to which prisoners are still smoking despite the smoking ban is unclear. A smoking ban was introduced in prisons in 2018 and smoking cessation services should be provided.

People in prisons should also be offered advice on diet, exercise, sexual health and contraception.54 Provision of these services should be tailored to need and exactly what this entails varies across the prison estate. People in prison should also be offered vaccinations such as the flu vaccine, in line with the clinical at-risk groups identified in the community.55

Substance misuse services

Integrated substance misuse services are an important part of health care within prisons. How services operate varies between prisons but NHS England has set out a framework highlighting the key aspects and principles, including the importance of focusing on recovery, partnership working and a comprehensive understanding of the needs of the particular population.56

Although drug-taking is banned in prisons, the use of novel psychoactive substances such as ‘spice’ is a particular challenge within the prison estate.57

Mental health

NHS England is responsible for commissioning mental health services. Many people in prison experience mental health problems – 71% of women and 47% of men58 – and they should receive care that is person-centred, provided by appropriately trained staff and be regularly reviewed to ensure they are given the right treatment and interventions. NHS England outlines a ‘stepped care’ model, with self-help at the bottom and specialist mental health services for those with marked mental illness at the top.59 People in prison may also meet the criteria for assessment and treatment under the Mental Health Act 1983. Importantly, mental health care should be integrated with other prison services, such as substance misuse services and care for physical health, and have a focus on rehabilitation.60

Guidance states that mental health services should also recognise the significance of trauma in the lives of many people who require a prison stay and its relationship with mental health (NHS England, 2018a). Some prisons have an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service and some also have ‘in-reach’ teams, which are multidisciplinary teams of health care professionals who support the mental health needs of people in prison. NHS England and NHS Improvement have recently commissioned a mental health needs analysis of services in order to attempt to quantify the level of need and service availability in the prison estate.61

The Centre for Mental Health has recently published The Future of Prison Mental Health Care in England, a review commissioned by NHS England and Improvement.62 Although it found that the current model of mental health care is working well and there are examples of innovative good practice, it also identified a number of challenges and areas for improvement. It also noted that, in reality, there is wide variation regarding what services are available across the prison estate (Durcan, 2021). The review also highlighted concerns about the screening process for people arriving at prison with mental health needs, continuity of care for people on release and delays in transferring people under the Mental Health Act 1983.63

The review put forward a number of recommendations to improve the provision of mental health care in prison, with a particular focus on:

- enhancing training for staff

- reducing short sentences and finding alternatives to prison for people with mental health problems

- fostering peer support programmes

- enhancing digital capability.64

The review also emphasised the importance of enacting the recommendations of the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act65, such as ensuring prisons are never used as a ‘place of safety’ for people who meet the criteria for detention under the Mental Health Act.66

Mother and baby units

The experiences of pregnant women and babies in prison have been highlighted due to two tragic deaths of new-born babies within 18 months, both of which are subject to ongoing investigation.67

Mother and baby units exist to support women in half of the 12 women’s prisons in England. The national operational capacity of these units is 64 mothers and 70 babies (to allow for twins and triplets).68

A recent review by the Ministry of Justice69 identified a number of reforms that needed to be made to improve the treatment of pregnant women in prison, including publishing more detailed data to inform care. A dedicated perinatal pathway is also due to be rolled out nationally across the women’s estate to support continuity of care for mothers and babies, but the Covid-19 pandemic has delayed this.70

On release

Transition into the community is a significant time for people in prison and steps must be taken to ensure continuity of care, particularly where people have begun programmes or treatment within prison. Continuity of care for people in prison is a key ambition within the NHS Long Term Plan, particularly through the RECONNECT programme.71 People with complex needs should have a pre-release health assessment at least one month before the release date, led by primary health care but involving multidisciplinary team members.72 People should be provided with a care summary and support for ongoing medication needs, and steps should be taken to liaise with relevant community services such as substance misuse, mental health and social services.73 Not all people in prison are registered with a GP when they enter prison and so they should be supported to do so on their release if that is the case. The Health and Justice Information Services should help to facilitate this.

What do we know about access to and quality of health care in prison?

In this briefing we have described what people in prison should theoretically receive with regards to health care. But, in practice, there are concerns about people’s access to and quality of health care in prison.74 The literature review we conducted for our previous research into and accompanying analysis of prisoners’ use of hospital services identified a number of issues.75

Natural causes are the main cause of death for people in prison, with the leading cause being disease of the circulatory system (43%) followed by cancer (32%).76 However, the Independent Advisory Panel on Deaths in Custody has suggested that many are preventable and a result of failings in health care management, such as a failure to recognise deterioration or poor management of long-term conditions – this is a particular concern for older prisoners.77 The charity INQUEST (2020)78 conducted a review of inquests and coroners’ reports and identified a number of areas of concern, including cancelled or delayed appointments, poor communication between health care and prison staff, and poor understanding of appropriate procedures.

Some studies have explored prisoners’ perspectives on their access to health care. Quinn and others (2018)79 conducted a qualitative study exploring offenders’ perspectives on factors that contributed to, or worked against, enabling and sustaining their access to health care. This highlighted the significant role of GPs in facilitating access, including the value of trusting relationships, flexibility and good communication.80 Edge and others (2020) explored the role of security constraints in prisoners’ access to secondary care and identified a number of challenges, including the need for escorts, stigma arriving handcuffed and a lack of confidentiality when prison officers are present at consultations.81

Access to and quality of prison health care must be understood within the wider context of prison policy and practice. Ismail (2019) used a qualitative study to understand the impact of austerity on prison health by conducting interviews with a number of international policy-makers.82 This identified a number of issues, including the ‘disappearing chain of accountability’, an increase in prison instability and longer waiting times.83 Another study looked at the impact in England specifically and found that a reduced workforce, increased availability of drugs, a prevalence of violence and political turnover all had an impact, among others.84 This wider instability has an effect on the prison’s ability to deliver health care services, for example by contributing to staff shortages, increasing waiting times and increasing security concerns.

Furthermore, staff shortages (such as not enough escorts) or security emergencies can affect how services are prioritised and who can access them. Security concerns also play a significant role in people’s experiences of secondary care services, including not being able to be told in advance when their appointment will be and impeding privacy during the appointment.85 The Covid-19 pandemic has also put extensive pressure on health care services, including within prisons, with changes to the wider prison regime impacting both the services people in prison have been able to receive as well as their long-term health care needs.

Our report on prisoners’ use of hospital services published in early 2020 described this use and some of the associated challenges with access and quality – for example, people in prison miss around 40% of outpatient appointments. Our accompanying report provides a comprehensive update on this work, as well as describes the services people used before they entered prison. Understanding how prisoners use health care services both before and during their prison stay is vital to ensuring that services are commissioned and organised to meet their needs.

Concluding thoughts

This briefing has described the services that should be provided to people in prison and highlighted some of the well-established challenges regarding access and quality. Our accompanying analysis of prisoners’ use of hospital services gives a fuller description of what this looks like in practice.

The context of prison health care is constantly evolving – the impact of the pandemic within the prison estate and wider society, and the changing nature of commissioning, are likely to influence the management of health care services as well as prisoners’ experience of these services. Monitoring the impact of these changes is vital to understanding the experiences of people in prison with regards to their health care and ensuring that services meet their needs.