Chronology: the first decade

1948

Background

Railways and electricity nationalised

State of Israel proclaimed

Marshall Plan

Transistor invented

Berlin airlift

Empire Windrush arrives

New town designation starts

NHS events

5 July 1948 NHS established

Development of specialist services: RHB(48)1

Medical Research Council (MRC) Social Medicine Research Unit (Central Middlesex)

1949

Background

Pound devalued to $2.80

NHS events

Powers to introduce prescription charges

Aureomycin, chloromycetin, streptomycin/PAS

Antihistamines

Cortisone and ACTH

Vitamin B12

Nurses Act creates regional nurse training committees

1950

Background

Korean war (1950–54)

NHS events

Link between smoking and lung cancer

Ceiling on NHS expenditure imposed

Bradbeer Committee appointed on internal administration of hospitals

Collings Report on general practice

1951

Background

Election: Conservative victory

Festival of Britain

NHS events

John Bowlby’s Maternal and child health care

Helicopters used in casualty evacuation in Korea

1952

Background

Death of King George VI

Harrow rail disaster

Barcode invented

NHS events

Danckwerts award for GPs

Watson and Crick establish the double helical structure of DNA

Chlorpromazine

London fog – thousands of deaths from pollution

College of General Practitioners formed

Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Death

1953

Background

Korean armistice

Elizabeth II crowned

Everest climbed

NHS events

Nuffield report on the work of nurses in hospital wards

Gibbon uses a heart-lung machine in heart surgery

Jerry Morris study of heart disease related to activity

1954

Background

Food rationing ends

First business computer (IBM)

NHS events

Cohen Committee on general practice

First kidney transplant (identical twin)

Daily visiting of children in hospital encouraged

Bradbeer Report

Beaver Committee on air pollution reports

1955

Background

Credit squeeze

Election: Conservative victory

Independent Television launched

NHS events

Acton Society Trust papers on NHS

Ultrasound in obstetrics

Group practice loan funds

1956

Background

Suez crisis

Hungarian rising

Dr John Bodkin Adams arrested

NHS events

Polio immunisation

Clean Air Act

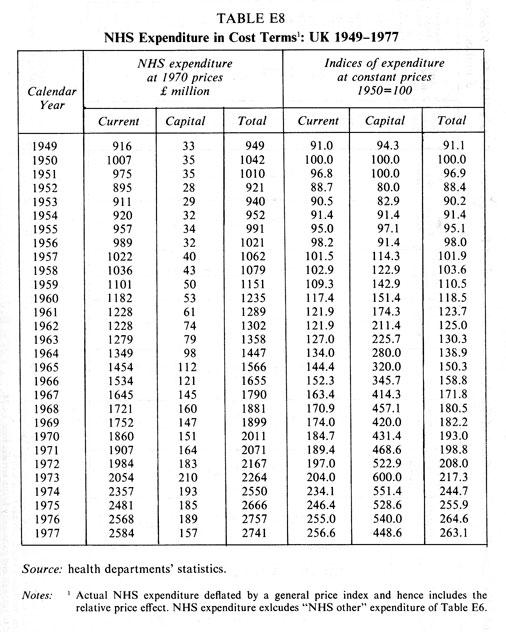

Guillebaud: Cost of the NHS

Large-scale trial of birth control pills

Working Party on health visiting (Jameson)

1957

Background

Macmillan Prime Minister

First satellites, Sputnik I and II

Royal Commission on Mental Illness reported

Treaty of Rome

NHS events

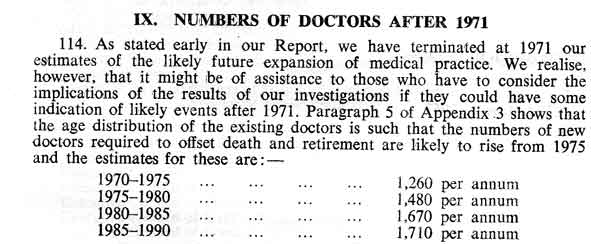

Willink report on future number of doctors

Royal Commission on doctors’ pay announced

Hospitals to complete the Hospital Inpatient Enquiry

Percy Commission on Mental Illness

On 5th July we start together, the new National Health Service. It has not had an altogether trouble-free gestation! There have been understandable anxieties, inevitable in so great and novel an undertaking. Nor will there be overnight any miraculous removal of our more serious shortages of nurses and others and of modern replanned buildings and equipment. But the sooner we start, the sooner we can try together to see to these things and to secure the improvements we all want . . . My job is to give you all the facilities, resources and help I can, and then to leave you alone as professional men and women to use your skill and judgement without hindrance. Let us try to develop that partnership from now on.

Message to the medical profession. Aneurin Bevan1

Preparing for the new service

For almost a century the government’s Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) had often begun their annual reports with an account of the year’s weather. It was a tradition going back to the Hippocratic view of its effect on health. Sir Wilson Jameson described the problems of 1947, the year before the NHS began.2

The eighth year of austerity, 1947, was a testing year. Its first three months formed a winter of exceptional severity, which had to be endured by a people who in addition to rationing of food were faced with an unprecedented scarcity of fuel. These three months of snow and bitter cold were followed by the heaviest floods for 53 years, which did great damage, killed thousands of sheep and lambs, delayed spring sowing and threatened the prospect of a good harvest which was so urgently needed. Immediately after these four months of disastrous weather there followed a period of economic crisis with an ever-increasing dollar crisis. So acute was the crisis that restrictions more rigorous than any in the war years became necessary. Bread had to be rationed for the first time late in 1946; in September 1947, the meat ration was reduced; in October the bacon ration was halved; and in November potatoes were rationed. A steep rise in the prices of foodstuffs and cattle food followed disappointing harvests in many European countries, due to the hard winter and hot dry summer, and in certain crops, notably corn for animal food, in America. Affairs abroad were as depressing as conditions at home.

The second world war had created a housing crisis. Alongside post-war rebuilding of existing cities, and the designation of overspill areas, the New Towns Act 1946 led to major new centres of population. The boundaries were drawn generously, land reclamation figured prominently and the problems of high-rise living were avoided. Most were clustered in the southeast. The planners covered thousands of acres of farmland, but they avoided tower blocks and the devastating results of the simultaneous redevelopment of the centres of older towns. The ethos and the pattern of the NHS had much in common with the newly nationalised state industries, railways, steel and the utilities. Beveridge, in his report in 1942, had proposed state funding but not how the NHS should work in practice.3 In 1944, before victory in Europe had been achieved, a committee within the Ministry had considered how the emergency hospital service would be ‘demobilised’. Bevan had worked out the details and the NHS had a command structure, a ‘welfare state’ ideology and was heavily dominated by those providing the services. On the appointed day, 1,143 voluntary hospitals with some 90,000 beds and 1,545 municipal hospitals with about 390,000 beds were taken over by the NHS in England and Wales. Of the ex-municipal beds, 190,000 were in mental illness and mental deficiency hospitals. In addition, 66,000 beds were still administered under Public Assistance, mainly occupied by elderly people who were often not sick in the sense of needing health care. Among the residents were some with irrecoverable mental illness, with a generous addition of ‘mental defectives’ and many old people who would now be regarded as having geriatric problems.

Designation of new towns

|

Crawley |

1947 |

|

Hemel Hempstead |

1947 |

|

Harlow |

1947 |

|

Newton Aycliffe and Peterlee |

1947 |

|

Welwyn Garden City and Hatfield |

1948 |

|

Basildon |

1949 |

|

Bracknell |

1949 |

|

Corby |

1950 |

Source: The Times 11 October 1996

Just before the service started, Aneurin Bevan sent a message to the medical profession. He spoke of the profession’s worries about discouragement of professional freedom and worsening of a doctor’s material livelihood – and said if there were problems they could easily be put right. He referred to a sense of real professional opportunity. In the same issue of the British Medical Journal (BMJ) on 3 July 1948, the editor was not so sanguine. While seeing the logic of spreading the high cost of illness over the whole of the community, it saw dangers in a state medical service, dogma, timidity, lack of incentive, administrative hypertrophy, stereotyped procedure and lack of intellectual freedom. However, much had been gained in negotiation over the previous months and now the medical profession would co-operate with the government. There was an opportunity to mould the service in partnership with the Ministry of Health. The service would have to evolve and there would be much trial and error. But the opportunity of building a healthy Britain would be grasped eagerly. “The pattern of events was clear,” said the BMJ, “The medical man, intensely individual, was becoming more and more aware of his responsibility to the community”.

Additional resources were negligible. The appointed day, 5 July 1948, brought not one extra doctor or nurse. What it did was change the way in which people could obtain and pay for care. They ceased to pay for medical attention when they needed it, and paid instead, as taxpayers, collectively. The NHS improved accessibility and distributed what there was more fairly. It made rational development possible, for the hierarchical system of command and control enabled the examination of issues such as equity.4 The Times pointed out that the masses had joined the middle classes. Doctors had become social servants in a much fuller sense. It was now difficult for them to stand aside from their patients’ social difficulties or to work in isolation from the social services.5 The Ministry, having worked for the establishment of the NHS, now became passive.

In making allocations to the regional hospital boards (RHBs) the Ministry of Health worked from what had been spent in the previous year. The boards took major decisions without fuss. Ahead of them lay the task of ‘regionalisation’, the development and integration of specialist practice into a coherent whole.6 Many reports were to hand, including the Hospital Surveys and the Goodenough Report on medical education.7 Bevan held a small dinner party on the first anniversary of the service to thank those who had been concerned with the preparatory stages. He toasted the NHS, and coupled the NHS with the name of Sir Wilson Jameson.

NHS managing bodies, 1948

- 14 regional hospital boards (RHBs)

- 36 boards of governors for teaching hospitals (BGs)

- 388 hospital management committees (HMCs)

- 138 executive councils (ECs)

- 147 local health authorities (LHAs)

There was uncertainty about who was in charge at region level. In most regions there was a viable partnership with no single boss. The senior administrative medical officer (SAMO) was university educated, but this was not necessarily true of the secretary, who drew a lower salary. Regional organisation varied and could be complex. In April 1956, Sheffield RHB had seven standing committees, six standing subcommittees, some chairman’s and many other advisory committees, 23 committees of consultants and a nursing advisory committee. There were also nine special committees, five ad hoc building committees, liaison committees with teaching hospitals and the university, and joint committees with other authorities on matters such as the treatment of rheumatic disease. The East Anglian region was simplicity itself: its last remaining committee (finance) had ceased to meet and the board did everything! The subordinate hospital management committees (HMCs) ran the hospitals and sometimes started to rationalise their facilities, but they had little influence on wider issues. Power increasingly lay at the RHB.

The Central Health Services Council

Standing advisory committees

The standing advisory committees remained in existence for over 50 years. There were four, each statutory and uni-professional: the Standing Medical Advisory Committee (SMAC) and its equivalents for nursing and midwifery (SNMAC), pharmaceutical services (SPAC) and dentistry (SDAC). They advised ministers in England and Wales when requested but also ‘as they saw fit’. Members were appointed by the Minister from nominations by the professions and included the presidents of the Royal Colleges. Their precise role changed over the years; initially they prepared guidelines on general clinical problems, usually through subcommittees.

The Central Health Services Council (CHSC), constituted by the 1946 NHS Act, was the normal advisory mechanism for the Ministry of Health. It had a substantial professional component alongside members representative of local government and hospital management.8 It was large and, after the first few years, met only quarterly, although several of its subcommittees remained influential. The Lancet believed that the Ministry never encouraged the CHSC to be a creative force. In its first 18 months, a host of novel and difficult problems faced the service and Bevan remitted 30 questions to it. He received advice from the Council on these and 12 other topics. At its first meeting, a committee was established to examine hospital administration, chaired for most of its existence by Alderman Bradbeer from Birmingham. Other issues included the pressure on hospitals and emergency admissions, the care of the elderly chronic sick, the mental health service, wasteful prescribing in general practice, and co-operation between the three parts of the NHS. Ten standing committees were established, some exclusively professional, and others to examine specific services such as child health, and cancer and radiotherapy.9 Over the first 20 years of the NHS, they produced a series of major reports that altered clinical practice, for example, on cross-infection in hospitals, the welfare of children in hospital, and human relations in obstetrics. The main committees were SMAC and SNMAC. Henry Cohen chaired SMAC for the first 15 years of the NHS. A general physician from Liverpool, his intellectual gifts made it possible for him to remain a generalist at a time when specialisation was becoming the order of the day.10 To begin with there was anxiety in the Ministry that SMAC would prove an embarrassment in its demands, but soon the members had exhausted the issues about which they felt strongly. George Godber found it best to provide SMAC with background briefing on an emerging problem and only then to ask for its advice. The Ministry could not give doctors clinical advice, but SMAC could and did – for example, that when drugs were in the experimental stage, or scarce, they should be restricted to use in clinical trials. Later they should be available solely through designated centres, and only when they were proven and in unlimited supply should control be no more than that necessary in patients’ interests.

Professional and charitable organisations

The introduction of the NHS affected many organisations that had taken part in the debates preceding the NHS. The British Hospitals Association, which had represented the voluntary hospitals, ceased to have a role and was rapidly wound up. The British Medical Association (BMA) continued at the centre of serious medical politics. For historic reasons GPs had always been powerful within it; they were many and they provided much of its money. When in 1911 Lloyd George’s national health insurance gave working men a doctor, GPs had to become increasingly active. The GPs’ Insurance Acts Committee was continued after 1948 as the General Medical Services Committee (GMSC), a standing committee of the BMA with full powers to deal with all matters affecting NHS GPs. The local medical committees elected it, as panel committees had done previously. It was not until 1948 that consultants had to enter the medico-political arena, which was new and unfamiliar to them. The consultants formed the Central Consultants’ and Specialists’ Committee, with powers analogous to the GPs’ committee as far as terms of service were concerned. The Joint Consultants Committee (JCC) succeeded the earlier negotiating committee, federating the BMA and the medical Royal Colleges, and represented hospital doctors and dentists in discussions with the health departments on policy matters other than terms of service. This complex system did not make for unity of the medical profession, particularly on financial matters.

The three Royal Colleges maintained powerful positions as a source of expert opinion and also in political matters. Charles Moran, Winston Churchill’s personal physician, (known familiarly as Corkscrew Charlie), was President of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) from 1941 to 1950. Alfred Webb Johnson led the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS), and their relationship was a little prickly. William Gilliatt, the Queen’s obstetrician, was President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). As his college dated only from the twentieth century it was regarded as the junior partner. The colleges were London dominated, and their presidents were usually southern; Robert Platt was the first provincial President of the RCP. The RCS had been damaged in the war and there was a chance of getting a neighbouring site so that all three Royal Colleges could be rebuilt together. Alfred Webb Johnson had a vision of a medical area in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, perhaps grandiose but it could have created a broad-ranging academy of medicine and a chance to develop methods of reviewing clinical practice.11 Moran stopped it, fearing that the RCP would become subsidiary. The RCS continued to encourage its own sub-specialties to develop and form close links with the parent organisation.

King Edward VII’s Hospital Fund for London (King’s Fund) had previously provided about 10 per cent of the income of London voluntary hospitals, but the state now funded these. It began to look at new fields, for example, the training of ward sisters, and catering.12 The Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust had fought for regionalisation, the pattern of organisation Bevan had adopted. It rapidly developed into a think tank on health service matters, but neither the Fund nor the Trust could maintain their direct influence on policy, although they were valuable sources of expertise.

More informal groups had existed before the establishment of the NHS. Wilson Jameson had his ‘gas-bag’ committee at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine where he was Dean. The same institution spawned the Keppel Club, in which young doctors from many disciplines came together from 1953 to 1974.13 A small society with a tight membership, it was entirely apolitical and met monthly for freewheeling and uninhibited discussion. There was an opportunity to discuss new methods and systems at an intellectual level. Membership was by invitation, and included Brian Abel-Smith, John Brotherston, John Fry, Walter Holland, Jerry Morris, Michael Shepherd, Stephen Taylor, Richard Titmuss and Michael Warren. Until it ended in 1974, when its members were busier and more senior, the club discussed such issues as child health, the care of the adolescent and the aged, general practice, hospital services, mental illness and the collection of information in the NHS.

The Royal College of Nursing (RCN), founded in 1916 as an association to unite trained nurses, emerged as a powerful body now that all nurses were working for the NHS. A decision was taken to discourage membership of mental illness nurses, who stayed with the Confederation of Health Service Employees (COHSE). COHSE hoped to become the industrial union for the NHS but other unions recruited nurses (the RCN), ancillary workers (the National Union of Professional Employees and the Transport and General Workers Union), administrative staff (the National Association of Local Government Employees), and laboratory and professional staff (the Association of Scientific Workers, later the Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs).14

National medical charities generally acted as pressure groups and they continued their work, now with the NHS in their sights. For example, there was the National Birthday Foundation that campaigned for the extension and improvement of maternity services, the National Association for Mental Health (Mind) promoting the interests of people with mental health problems, and the Association of Parents of Backward Children (later Mencap).

Medicine and the media

Newspaper and magazine articles on professional issues were uncommon. Medical authors were suspected of advertising, an offence for which they might be struck off the register. Doctors and nurses had mixed views about the media. Some believed that there would be widespread hypochondriasis if it was no longer possible to keep people in ignorance of hospital care and their treatment. Television was slowly spreading from London throughout the country, but as late as 1957, only half the households had a set, and among the professional classes there were even fewer. Educated people often talked about television without actually having seen it. ‘Emergency – Ward 10’, one of the earliest popular programmes, was thought to help nurse recruitment but was creating a modern mythology about nurses and hospital treatment.15 When BBC TV ran a programme on slimming and diet, the BMJ was alarmed by “this somewhat curious experiment that approached the public over the heads of the practising doctor”.16

Medical progress

Health promotion

Health education had been pursued during the years of war. The approach remained mass publicity on all fronts. Messages were didactic and concentrated on the dangers in the home, infectious disease, accident prevention and, in the 1950s, the diagnosis of cancer of the breast and cervix.17 There was little evidence that this technique, largely modelled on the advertising world, worked. Many doctors felt that the less patients knew about medicine the better, as Charles Fletcher, a physician at the Hammersmith Hospital, discovered to his cost when he advocated pamphlets for patients, explaining the causes of their illnesses and what to do about them.18 In 1951 the BMA launched a new popular magazine, Family Doctor. Primarily a health magazine, its aim was to present simple articles on how the body worked, the promotion of health, and the prevention of disease. The editor believed passionately that education and persuasion to adopt a different life style could improve the health of the nation. He felt that the time was past when medicine could be regarded as a mystery. Some subjects, however, were taboo, contraception being one of these.19

Jeremy Morris, (1910–2009), a life long socialist and epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, laid foundations for the promotion of exercise as important for health. In a study with London Transport which lasted many years, he found that the drivers of London’s double-decker buses were more likely to die suddenly from “coronary thrombosis” than the conductors, and that government clerks suffered more often from rapidly fatal cardiac infarction than postmen.

Incidence of ischaemic heart disease in bus drivers and bus conductors

|

Age(years) |

Conductors Incidence rate per 100 men in 5 years |

Drivers Incidence rate per 100 men in 5 years |

|

40–49 |

1.6 |

7.6 |

|

50–59 |

5.1 |

9.8 |

|

60–69 |

7.4 |

7.9 |

|

Total |

4.7 |

8.5 |

Source: Morris JN, Kagan A, Pattison DC and Gardner MJ. Incidence and prediction of ischaemic heart disease in London busmen. The Lancet 1966; 2(7463): 553–9.

Bed rest

One of the most important clinical developments was simplicity itself. Richard Asher was a physician at the Central Middlesex Hospital who combined clarity of thought, deep understanding of the everyday problems of medicine and sparkling wit. It was he who gave Munchausen’s syndrome its name, after the famous baron who travelled widely and told tales that were both dramatic and untrue. In 1947 he was among the earliest to identify the dangers of institutionalisation and going to bed.20

It is always assumed that the first thing in any illness is to put the patient to bed. Hospital accommodation is always numbered in beds. Illness is measured by the length of time in bed. Doctors are assessed by their bedside manner. Bed is not ordered like a pill or a purge, but is assumed as the basis for all treatment. Yet we should think twice before ordering our patients to bed and realise that beneath the comfort of the blanket there lurks a host of formidable dangers.

Asher pointed to the risks of chest infection, deep vein thrombosis in the legs, bed sores, stiffening of muscles and joints, osteoporosis and, indeed, mental change and demoralisation. He ended with a parody of a well-known hymn:

Teach us to live that we may dread

Unnecessary time in bed.

Get people up and we may save

Our patients from an early grave.

The medical profession, although not immediately convinced, recognised that here was an issue to be explored. Francis Avery Jones, a gastroenterologist at Asher’s hospital, later said that early ambulation saved the health service tens of thousands of beds, and many people their health and lives. Doctors had previously equated close and careful post-operative supervision with keeping people in bed; once they were out of bed there was a danger of premature discharge, and fatal pulmonary embolus might occur. For example, the BMJ said that a surgeon would be in a difficult position if he allowed a patient to be discharged the fourth day after appendicectomy or the seventh day after cholecystectomy (as happened in the USA) and developed a fatal embolus in the second week.21 The probability that the embolus was the result of the closely supervised bed rest was not appreciated.

Surgeons were concerned that incisions would not heal if patients got up too soon, but Farquharson, at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, wrote that the cause of morbidity and mortality after an operation was usually remote from the actual wound. He believed that there was little evidence that wounds needed bed rest to heal. He proved his point by operating on 485 patients with hernia under local anaesthetic and discharging them home before the anaesthetic had worn off. Only one patient out of 200 needed readmission. The patients liked early discharge, they waited only a few days for operation, and the financial savings were considerable.22

The quality and effectiveness of health care

Doctors seldom looked at their clinical practice and its results. When, around 1952, a paper was put to the JCC that included lengths of stay, one physician loftily said: “all that is needed is that a consultant should feel satisfied that he has done his best for the patient. This arithmetic is irrelevant.” Death was the clearest measure of outcome, and infant and maternal mortality were studied – but comparisons of the results of different types of treatment were rare. On occasion clinicians might seek Ministry support for medical review projects, but it had to be covert and not an attempt to impose a central system. The use of randomised controlled trials now provided a way of validating clinical practice and the effectiveness of treatments. Matching cases by human judgement was open to error; randomisation involving large numbers provided an even dispersion of the personal characteristics likely to affect the outcome. The principles were established by D’Arcy Hart and Austin Bradford Hill. Austin Bradford Hill crashed three aircraft without injury while serving in the first world war but subsequently developed tuberculosis, which barred him from clinical medicine. He read economics, got a grant from the Medical Research Council (MRC), moved to the London School of Hygiene and determined to make a life in preventive medicine. An inspiring writer, many of his ideas passed into common usage; he understood the ethical and clinical problems that doctors faced, and could convince senior members of the profession that they should adopt controlled trials. A friend of Hugh Clegg, Editor of the BMJ from 1947, Hill chose that journal for his publications because of its wide circulation among doctors of all specialties. Clegg wanted good scientific papers and accepted long summaries because many doctors would not be prepared to read the entire papers.23 Hill fed Clegg the MRC’s report on the randomised trial of streptomycin in the treatment of tuberculosis, the trials of cortisone and aspirin in rheumatoid arthritis and the trial of whooping cough vaccine. Though a powerful tool, randomised trials were not always applicable; in surgery, for example, randomisation was not always practicable.

The MRC worked with the Ministry of Health and began to establish clinical research units. The provincial universities developed academic units more rapidly than London; for example, Robert Platt, Professor of Medicine in Manchester, and Henry Cohen, Professor in Liverpool. The medical press and contacts between doctors had always helped the dissemination of new clinical ideas. Now the NHS provided a new mechanism. It was said that those in the Ministry could achieve anything if they did not insist on claiming credit. Many doctors would take up a good idea when it was drawn to their attention, if the approach was tactful. SMAC could be asked to look at specific clinical problems. Regions could then be given guidance that would be adopted throughout the country if it was seen to accord with professional thinking. Once a new idea was spotted, it could be nurtured. Doors could be opened to let people through. Organisations such as the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, the King’s Fund and the Ministry worked quietly together. Some doctors were natural originators, others born developers, and both could be supported. Those seeing the way ahead would try to get others to follow. Postgraduate education, statistical methods, the use of controlled trials, group general practice and the development of geriatric and mental illness services were all ideas fostered and given a platform.

The drug treatment of disease

Before the second world war, many drugs had no effect, for good or ill. Placebo prescribing was commonplace, with a reliance on the patient’s faith. The first decade of the NHS saw the discovery of a staggering array of new and potent drugs. The drugs that were being developed were expensive and sometimes difficult to produce. Usually they were not immediately released for general use. The tetracyclines and cortisone were not available on GP prescription until 1954/5 when industrial-scale production facilities had been created. Inevitably costs rose. At the end of the 1949 parliamentary session, power was obtained to levy a prescription charge.24 It was not used immediately but was invoked by the next government and used almost continuously and increasingly thereafter.

Penicillin and streptomycin were available when the NHS began but it was not known how they worked. Biochemistry and cell biology had not developed sufficiently for the underlying mechanisms to be understood.25 Syphilis and congenital syphilis were among the diseases conquered. Within the next year, aureomycin, the first of the tetracyclines, was discovered and proved to be active against a far wider range of organisms. The response of chest infections to antibiotics rapidly revealed a group of non-bacterial pneumonias, previously unsuspected, caused by viruses and rickettsial bacteria. Chloramphenicol was isolated from soil samples from Venezuela and soon synthesised; it worked in typhus and typhoid. In 1950 terramycin, another tetracycline, was isolated in the USA from cultures of Streptomyces rimosus. In 1956 a variant of penicillin, penicillin V, became available that could be given by mouth, avoiding the need for painful injections.26

The clinical exploitation of a new antibiotic usually passed through two phases: first, over-enthusiastic and indiscriminate use, followed by a more critical and restrained appraisal. Some strains of an otherwise susceptible organism were, or became, resistant to the drug. An early example was the reduction in efficacy of the sulphonamides in gonorrhoea, pneumonia and streptococcal infections. Penicillin withstood the test of time more successfully, but Staphylococcus aureus slowly escaped its influence and became resistant. Resistance of the tubercle bacillus to streptomycin was quickly acquired, and resistance was also a problem with the tetracyclines.27 Erythromycin was discovered in 1952, resembled penicillin in its action, and by general agreement was reserved for infections with penicillin-resistant bacteria.28 It became policy to use antibiotics carefully and to try to restrict their use.29

Cortisone, demonstrated in 1949 at the Mayo Clinic, did not fulfil all early expectations. It had a dramatic effect on patients with rheumatoid arthritis and acute rheumatic fever, but this was often temporary.30 Supplies were limited because the drug was extracted from ox bile and 40 head of cattle were required for a single day’s treatment. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was even more difficult to obtain, being concentrated from pig pituitaries. Quantities were therefore minute and costs were high, so more economic methods of production were sought. By 1956 prednisone and prednisolone, analogous and more potent drugs, had been synthesised and were in clinical use. Like cortisone they were found to be life-saving in severe asthma. Few effective forms of treatment had been available to dermatologists. Now there were two potent forms of treatments: antibiotics for skin infection and corticosteroids that had a dramatic effect on several types of dermatitis.

The outcome of patients with high blood pressure was well known because there was no effective treatment. Four grades of severity were recognised, based on the changes in the heart, the kidneys, and the blood vessels in the eyes. In severe cases, grades three and four, the five-year mortalities (death within five years of diagnosis) were 40 per cent and 95 per cent. Surgery (lumbar sympathectomy) might prolong survival but in 1949 hexamethonium ‘ganglion-blocking’ drugs were introduced, and the era of effective treatment had begun. At first, drugs had to be given by injection but preparations that could be taken by mouth were soon available. None of the alternatives approached the ideal: surgery was not particularly successful; dietary advice and salt restriction made life miserable; reserpine made patients depressed; and ganglion-blocking drugs had severe side effects, including constipation, fainting and impotence. Only people with the most severe hypertension were therefore considered for treatment.31

Vitamin B12 was synthesised and liver extract was no longer required in the treatment for pernicious anaemia.32 Insulin had been used in the treatment of diabetes since the 1920s but a new group of drugs suitable for mild and stable cases, the oral hypoglycaemic sulphonamide derivatives, were developed. They simplified treatment, particularly in the elderly, and reduced the need for hospital attendance.33 The antihistamines were introduced mainly for the treatment of allergic conditions. They were associated with drowsiness which, in drivers, caused traffic accidents. Reports from the USA that they cured colds were examined by the MRC; the drugs were valueless. The common cold had again come unscathed through a therapeutic attack.34

Chlorpromazine was introduced in 1952 for the treatment of psychiatric illness. It produced a remarkable state of inactivity or indifference in excited or agitated psychotics and was increasingly used by psychiatrists and GPs.35 The tranquillisers, for example, meprobamate, also represented a substantial advance. Barbiturates had been used for 50 years, but they were proving to be true drugs of addiction and were commonly used in suicides.36 The new drugs undoubtedly had a substantial impact on illnesses severe enough to need hospital admission, but whether they helped in the minor neuroses was less certain.37 William Sargant, a psychiatrist at St Thomas’, referred to the extensive advertising and the shoals of circulars through the doctor’s letterbox. Big business was beginning to realise the large profits to be made out of mental health. All that was necessary was to persuade doctors to prescribe for hundreds of thousands of patients each week.38

Halothane, a new anaesthetic agent, was carefully tested before its introduction, although repeated administration in a patient was later shown to be associated with jaundice.39 It was neither inflammable nor explosive. Explosions during ether anaesthesia, often associated with sparks from electrical equipment, occurred and inevitably killed some patients.

For many years there had been concern about adverse reactions to drugs and the best way to recognise them. As the pharmaceutical industry developed an ever-increasing number of new products, anxieties increased.40 The problem came to a head in the USA in 1951, when a few patients were reported in whom chloramphenicol had produced fatal bone marrow failure (aplasia). The American Medical Association appointed a study group to examine all cases of blood disorders suspected of being caused by drugs or other chemicals. The problem was thought to be rare, because chloramphenicol had been widely used, yet it was found that there had in fact been scores of cases of aplastic anaemia and it had taken three years to appreciate the potential toxicity. There was rapid agreement that its use should be limited to conditions untreatable by other means.41

In 1956, Dr John Bodkin Adams was arrested for murder following the death of many of his patients, often elderly ladies who had left him substantial sums in their wills. Between 1946 and 1956, 160 died under suspicious circumstances. He was acquitted but later convicted of false statements on cremation forms and offences under the Dangerous Drugs Act. Opinion remains divided as to whether he was a mass murderer or an early proponent of euthanasia. He was restored to the Medical Register in 1961.

Radiology and diagnostic imaging

Tests and investigations were playing an increasing part in the diagnostic process. Radiology revealed the structural manifestations of disease, but the basic technology had not changed greatly since 1895 when the first films were taken. An X-ray beam produced a film for later examination, or the patient was ‘screened’ and the image was examined directly in a darkened room. The radiation exposure was higher with screening and the radiologist had to become dark-adapted before he could work. From the 1930s radiology developed rapidly, but hospital services were handicapped by a shortage of radiologists.

Three developments gave radiology a new impetus. First, in 1954 Marconi Instruments displayed an image intensifier, which produced a much brighter image, although the field was only five inches (12.7 cm) wide. It was visible in subdued light and good enough to photograph. The technique was immediately applied to studies of swallowing. Secondly there were improvements in contrast media, used to visualise blood vessels. They were often unpleasant and sometimes risky. From the 1950s new ‘non-ionic’ agents were introduced. Cardiac surgery was developing fast and catalysed developments in radiology; for example, angio-cardiography in which contrast medium was injected into the blood vessels leading to the heart before a series of X-rays.42 The third development, in 1953, was the introduction of the Seldinger technique. This made possible percutaneous catheterisation, the introduction of a fine catheter into a blood vessel, thus avoiding the need for an incision. A tracer guide wire could be inserted and imaged, and when in position a catheter slid over it. Contrast medium could be injected selectively into blood vessels, under direct vision using the image intensifier, just where it was required.43

The availability of radioactive isotopes (radio-isotopes) led to the development of nuclear medicine and a new method of imaging. Radio-isotopes could be introduced into the body, sometimes tagged to tissues such as blood cells. As they were chemically identical to the normal forms, they were handled by the body in the same way. It was possible to measure the presence and amount of the radio-isotope, its spatial distribution and its chemical transformation. The new techniques provided a way of studying, at least crudely, some of the body’s functions, as opposed to its structure. Isotopes were chosen to minimise the radiation dose as far as possible. At first, radioactive tracer work was the province of the pathologist, as in studies of blood volume and circulation. The development of gamma cameras and rectilinear scanners, however, meant that images could be produced as well as ‘counts’, and radiologists came to the fore.44

Early in 1955 the MRC, at the request of the Prime Minister, established a committee chaired by Sir Harold Himsworth to report on the medical aspects of nuclear radiation. Its report, a year later, contained the unexpected finding that exposure of the gonads to diagnostic X-rays significantly increased the irradiation received, by some 22 per cent.45 The fall-out from testing nuclear weapons was less than 1 per cent. Shortly after, Dr Alice Stewart published a report suggesting that childhood leukaemia was associated with irradiation of the fetus (and also with virus infection and threatened abortion).46 Her findings were not accepted until a second study from the USA confirmed a connection with irradiation during pregnancy. Although radiologists were already concerned about the dangers of radiation exposure, there was some delay in taking greater precautions during pregnancy.

Infectious disease and immunisation

Deaths in England and Wales from infectious disease

|

Tuberculosis |

Diphtheria |

Whooping cough |

Measles |

Polio |

|

|

1943 |

25,649 |

1,371 |

1,114 |

773 |

80 |

|

1944 |

24,163 |

1,054 |

1,054 |

243 |

109 |

|

1945 |

23,955 |

722 |

689 |

729 |

139 |

|

1946 |

22,847 |

472 |

808 |

204 |

128 |

|

1947 |

23,550 |

244 |

905 |

644 |

707 |

|

1948 |

23,175 |

156 |

748 |

327 |

241 |

|

1949 |

19,797 |

84 |

527 |

307 |

657 |

|

1950 |

15,969 |

49 |

394 |

221 |

755 |

|

1951 |

13,806 |

33 |

456 |

317 |

217 |

|

1952 |

10,585 |

32 |

184 |

141 |

275 |

|

1953 |

9,002 |

23 |

243 |

245 |

320 |

|

1954 |

7,897 |

8 |

139 |

45 |

112 |

|

1955 |

6,492 |

12 |

87 |

174 |

241 |

|

1956 |

5,375 |

3 |

92 |

28 |

114 |

|

1957 |

4,784 |

4 |

87 |

94 |

226 |

|

1958 |

4,480 |

8 |

27 |

49 |

154 |

The decade saw the end of smallpox as a regular entry in public health statistics, the decline of diphtheria and enteric fever to around 100 cases per year, the greatest ever epidemic of poliomyelitis, and a substantial rise in food poisoning and dysentery, possibly related to better diagnosis now available through the Public Health Laboratory Service (PHLS). It is hard nowadays to appreciate the misery and deaths caused by infectious diseases, which were common and potentially lethal. In 1948 there were 3,575 cases of diphtheria with 156 deaths. Tuberculosis remained a major problem, although notifications to the Medical Officer of Health (MOH) and deaths were steadily getting fewer. There were 400,000 notifications of measles with 327 deaths, and 148,410 of whooping cough with 748 deaths. The USA had introduced diphtheria immunisation in the 1930s, but it was not until 1940/1 that local authorities, spurred by Wilson Jameson, launched a major campaign in the UK. A long-forgotten clause in a Public Health Act gave local authorities the power to do so. Whooping cough, tetanus and polio immunisation followed. As new vaccines were introduced, each was usually given three times; the schedule for infants became increasingly complex until ‘triple’ vaccines improved matters.

There had been small sporadic outbreaks of poliomyelitis for many years, but the disease assumed epidemic proportions in 1947. Thereafter the numbers fluctuated, but remained at a historically high level for several years with 250 to 750 deaths annually. It was the custom for cases to be admitted to isolation hospitals, and then transferred to orthopaedic hospitals for the convalescent and chronic stages. Oxford established a team including specialists in infectious disease, neurology and orthopaedics so that patients with severe paralysis could be assessed jointly from the start. Respiratory support with ‘iron lungs’ was available and passive movement of the limbs reduced the risks of later deformity. The tide turned when Jonas Salk developed an inactivated vaccine in the USA and reported the success of field trials in 1955.47 Manufacture began in Great Britain under the supervision of the MRC, and immunisation of children started in 1956.

Bacterial food poisoning was an increasing problem. Imported egg products from North and South America and, after the war, from China, sometimes contained Salmonella. Synthetic cream was associated with many outbreaks of paratyphoid fever, and spray-dried skim-milk was responsible for outbreaks of toxin-type food poisoning.

Cases of smallpox occurred intermittently. In 1950 there was an outbreak in Brighton, introduced by a fully vaccinated RAF officer recently returned from India. There were 26 cases, 13 of which were among nursing and medical staff, domestics and laundry workers at the hospital to which the earliest cases were admitted, and ten deaths.48 In 1952, an outbreak in Rochdale led to 135 cases with one death, and there were further importations in succeeding years.

The death rate from tuberculosis had begun to decline after the first world war, but the incidence was still high, and primary infection occurred in nearly half the children before they were 14. When the NHS began, there were 50,000 notifications a year and 23,000 deaths. Before streptomycin, doctors relied on the natural resistance of the patient, aided by bed rest and the indirect effect of ‘collapse’ therapy. To reduce the movement of diseased lung tissue, in the hope that this would assist healing, sections of the rib cage were removed (thoracoplasty), air was introduced to collapse the lung (artificial pneumothorax) or the phrenic nerve would be divided to paralyse the diaphragm. Antibiotics attacked the tubercle bacillus directly. There was insufficient streptomycin to treat everyone who might benefit, and supplies went to those in whom the best results could be expected, young adults with early disease. A rigorously controlled investigation run by D’Arcy Hart and the MRC confirmed the effectiveness of streptomycin. In a second trial, the newly discovered para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) was proved to prevent the development of bacterial resistance, and a third trial examined the level of dose required.49 In 1952 isoniazid was introduced. Given alone it was no better than streptomycin and PAS, and patients could rapidly develop drug resistance. However MRC trials and the work of Professor Sir John Crofton (1912–2009) in Edinburgh showed that it was not which drugs were given that mattered, but in what combination and for how long. As success could only be assessed by the absence of a relapse in subsequent years, it took time to establish the best options. Triple-drug therapy over 18 months to two years greatly reduced the problem of the emergence of resistant strains of tubercle bacilli, but some clinicians were slow to adopt the protocols that gave such excellent results. The results were so good that collapse therapy and surgical methods of treatment were used far less frequently.50 An MRC trial in India showed that, even under the worst social conditions, patients rapidly ceased to be infectious if they took their treatment. There was no need to admit patients for long periods to reduce the risk of infection to families and the community. For the first time, early treatment of tuberculosis had major benefits, yet there was an average delay of four months between the first consultation and a diagnostic X-ray; GPs were urged to refer patients more rapidly.51

In the drive for early treatment, disused infectious disease wards were used, a good example of the new opportunities open to the NHS. In 1948 the waiting list figures had convinced the Manchester Regional Hospital Board that a new sanatorium was urgently required. By 1953 it had not been built, but it was now no longer needed because the waiting time for admission had fallen from nine months to a few weeks.52 Within a few years, beds for tuberculosis and the fevers were being turned over to newly developing specialist units, for example, neurosurgery. After a successful trial of the tuberculosis vaccine BCG (bacillus Calmette-Guérin) by the MRC, immunisation at the age of 13 was introduced, reducing further the number of new infections. Mass mobile radiography units were important tools in ‘case-finding’. The vans would visit centres such as colleges and hospitals where there were many young people, and 35mm pictures were taken of images produced by fluorescent screening.

There was a major influenza outbreak in 1951/2. From 5 to 8 December 1952 ‘smog’ (fog filled with smoke) of unusual density and persistence covered the Greater London area. People piled coal onto their fires to keep warm. To most, smog was no more than an inconvenience. Those with chronic heart and lung disease were less lucky. Their illnesses got worse and many died. Dying people, their lips blue from lack of oxygen were forced to walk to the hospital because ambulances stopped running. For some years an ‘emergency bed service’ had operated in London, finding beds for emergency admissions by phoning round the hospitals. It came under pressure and immediately restricted non-urgent admissions, but the media were first to spot the severity of the problem. Florists ran out of flowers for funerals. Newspaper articles drew attention to the death of prize cattle at the Smithfield show. Not until the death certificates had been assembled was the full severity of the episode apparent; there were 3,500–4,000 excess deaths.53 St George’s (Hyde Park Corner), like all London hospitals, admitted many victims of bronchitis and heart failure; as it was not possible to see from one end of a ward to the other, they were divided in two so that patients could be properly observed. A committee chaired by Sir Hugh Beaver was set up in July 1953, which rapidly identified the importance of pollution from solid fuels. Its recommendations, (which smoke abatement groups had been suggesting for almost a century), formed the basis of a single comprehensive Clean Air Act on 5 July 1956. Emission control was required; industry had to change and methods of manufacturing had to alter. It became an offence to emit dark smoke from a chimney, and local authorities could establish smoke control areas. Following the legislation, the age-specific death rates of men in Greater London fell by almost half. The opposition to the control of atmospheric pollution, for example, from industry, was slight. This was not the case with smoking; although its hazards were far greater, there were issues of individual choice and liberty, and much more antagonism from industry.

Rheumatic fever, associated with streptococcal throat infection, was another common disease of childhood normally requiring admission to hospital. More frequent among the poor, there would be fever, pain and stiffness in the larger joints. Although some children might die of the acute illness (700 in 1949, falling to 174 in 1957), the main problem was that about half developed rheumatic disease of heart valves, which became incompetent (they leaked) or stenosed (they obstructed blood flow). The result was progressive heart failure in adolescence or later in adult life.

Milder infections were not ignored. At Salisbury, the Common Cold Research Unit had been established before the war to examine this difficult problem. Volunteers turned up every fortnight to help the scientific work. By 1950 they numbered more than 2,000, including 253 married couples, several being on their honeymoon.54

The incidence of venereal disease had increased in both world wars. After 1945 the level began to fall and many venereologists thought seriously of leaving what seemed to be a dying specialty. Venereal disease responded to antibiotics: syphilis was rapidly cured, and cases of congenital syphilis fell steadily as antenatal testing became routine, followed by treatment where necessary. The reduction in gonorrhoea, however, levelled off and drug-resistant strains became apparent. By 1955 the levels were rising again, and they continued to do so. Dr Charles, the CMO, said that sexual promiscuity was as rife as it had ever been in times of peace, and while this was the case, the venereal peril would be ever with us.55

The PHLS expanded as ‘associated laboratories’ were incorporated into the main network. Increasingly the laboratories were located on the site of acute hospitals and came to provide bacteriological services to the hospital as well as to the local authorities responsible to assist the control of infectious disease. The PHLS was becoming involved both in the care of individuals and in the health of ‘the herd’. From the early days the PHLS wanted to recruit epidemiologists, but this was opposed by the Ministry and the medical officers of health (MOsH). From 1954 its weekly summary of laboratory reports contained hospital as well as community data, and became a comprehensive account of the prevalence of infection. The PHLS was also deeply involved in the study of hospital-acquired staphylococcal infection, for patients in surgical wards were increasingly infected by resistant strains. First detected in 1954, the problem spread rapidly and led to the appointment, in most hospitals, of infection-control nurses. The management of the service was reviewed in 1951 and the MRC was asked to continue to run it.

Orthopaedics and trauma

War has always produced medical innovations. The Korean War (1950–54) saw the introduction of helicopter evacuation, which in turn led to a reappraisal of the early treatment of injury. Within days of the Air Force choppers’ arrival, the US Eighth Army’s surgeon general asked for their help in evacuating critically wounded soldiers from the front. Thereafter, when they were not flying search-and-rescue missions, they pitched in to get the wounded to hospitals. In the first month alone, the Air Rescue choppers evacuated 83 critically wounded soldiers, half of whom, the Eighth Army surgeon general said, would have died without the airlift. The system was soon formalised and the infantry came to see that, if not killed outright, their chance of survival was now good. During their first 12 months of operation in 1951, Army helicopters carried 5,040 wounded. By mid-1953 Army choppers evacuated 1,273 casualties in a single month. “Costly, experimental and cranky, the helicopter could be justified only on the grounds that those it carried, almost to a man, would have died without it,” an Army historian concluded. It was many years before the lessons learned were applied to civilian trauma care.

Image: Barbara Hepworth painted a series of 60 images of surgeons and nurses, circa 1947.

The 1939–1945 war had given orthopaedic surgery impetus. During the latter part of the war, orthopaedic surgeons began to encounter, among prisoners of war repatriated from Germany, fractures treated by inserting a nail throughout the length of the marrow cavity. The method, originally described by Küntscher, was soon seen to be a success, making possible a shorter hospital stay.56 British surgeons, for example Sir Reginald Watson-Jones, were also developing and using internal fixation for fractures of the femoral neck. In 1949 Robert Danis of Brussels described a system of rigid internal fixation that allowed anatomically accurate reduction, compressing the fracture surfaces. This made it easier to get patients up and moving. Because of early rehabilitation, complications of treatment were reduced and there were far fewer bed sores and deaths from thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.57 At first the plates and screws used were copied from those familiar in joinery; later they were redesigned for the specific needs of fracture surgery. As understanding of fracture healing improved, there was growing recognition that stable fixation of a fracture had immense benefits in terms of restoring the soft tissues for which the bone serves as a scaffold. In addition to the techniques of internal fixation, putting strong inert screws into the fragments of bone and holding them with a light but rigid external fixation system made it possible to correct major damage to soft tissue, vessels and nerves.

The other major pressure on orthopaedic departments was osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis of the hip was a common and painful condition. Several operations had been devised that relieved pain at the cost of mobility, for example, arthrodesis that fused the femur to the pelvis. Among the more successful was Smith-Petersen’s procedure, involving the reshaping of the joint surfaces and the insertion of a smooth-surfaced cup of inert metal between the moving parts. Re-operation was sometimes required. Arthroplasty, the total replacement of the joint by an artificial socket and femoral head made to fit each other, gave patients a new and mechanical joint. The procedure was first carried out by Kenneth McKee in Norwich around 1950, using cobalt-chrome components.58 No great attention was paid to the surface finish or fit, and the method of fixation proved inadequate. Friction in the joint was high and there were both failures and successes. Some of his patients were seen by John Charnley at a meeting of the British Orthopaedic Association, who considered that the procedure might be improved. The Manchester RHB funded him to develop a new unit near Wigan to refine it. The engineering problems were substantial and the results, to begin with, were not always predictable.

In 1952, 112 passengers were killed and 200 were seriously injured in a three-train collision at Harrow. There was chaos. By modern standards, the fire and ambulance services were hopelessly inadequately equipped, and were untrained to keep trapped people alive. All that could be done was a little bandaging and to take people to hospital as fast as possible. Edgware General Hospital learned of the crash when a commandeered furniture van arrived with walking wounded. Among those responding to the disaster were US teams from nearby bases, who were trained in battlefield medicine. They were disciplined, brought plasma and undertook triage – sorting casualties into those needing urgent attention, those who could wait, and those who were beyond help. It was a new experience for the rescue services; they were amazed and full of admiration.59 Yet the lessons were not learned for many years. In December 1957, another train crash occurred in thick fog near Lewisham. The ambulances moved 223 people, and 88 died in the accident. The SAMO, James Fairley, called for reports. As at Harrow, there were failures in communication, difficulty in identifying senior staff at the site, inadequate supplies of dressings and morphine, a shortage of ambulance transport, and difficulties in creating records and documenting the injured.60

Major trauma was also increasing on the roads as traffic was becoming denser. By 1954 there were more than one million motorcycles on the road, and over 1,000 deaths among their riders. Crash helmets were seldom worn and the neurosurgical units picked up the problems.61 Roughly 50,000 people required admission for head injury annually, and three-quarters of road fatalities were the result of this. The few neurosurgical units whose primary concern had been with tumours were increasingly asked to care for patients with head injury. More units were opened, improving accessibility. Walpole Lewin, in Oxford, argued for regional planning in close association with a major accident service.62 Research work at the Birmingham Accident Hospital improved the treatment of injury immeasurably. It was widely recognised that severe collapse after major injury was associated with a vast fall in blood volume, far greater than could be accounted for by external loss. Where had the blood gone, and what should the treatment be? Blood volume studies after accidents made it clear that huge amounts of blood were lost from the circulation into the swelling around fractures. Major burns led to a similar depletion of circulating blood volume. Rapid and large blood transfusion saved lives. Lecturing to the St John’s Ambulance Brigade, Ruscoe Clarke appealed for the re-writing of first-aid textbooks. The hot cup of tea and a delay while patients got over the shock of injury had to go; time was not on the patient’s side and recovery would only begin after transfusion and surgery.63 He provided the Association with new text for its handbooks.

Cardiology and cardiac surgery

In the 1940s the only methods available for the diagnosis of heart disease, other than bedside examination, were simple chest X-rays and the three-lead electrocardiograph. The effective drugs were morphia, digitalis and quinidine.64 The management of heart disease was about to change out of all recognition. It was a subject that attracted the cream of the profession; Paul Wood at the National Heart Hospital was only one among a number of clinicians who educated a new generation of doctors about valvular, ischaemic and congenital heart disease, taught new ways of listening to the heart and interpreting what was heard, and opened new pathways in treatment.65 Were he to have a heart attack, Wood did not wish to be resuscitated. When he did, some years later, he was not.

Infective disease of the heart had been a major problem but the effectiveness of antibiotics in streptococcal infections, which might otherwise have been followed by acute rheumatism, began to change its incidence. Syphilitic heart disease with aortic incompetence (valve leakage) was yielding to arsenicals, heart damage as a result of diphtheria to immunisation, and infection of heart valves following rheumatic fever to antibiotics.66

There was little effective treatment for coronary artery disease, an increasing problem. Coronary arteries might slowly become narrowed, and a heart attack (myocardial infarction) would occur if arteries suddenly became blocked. Losing its blood supply, heart muscle would be damaged, abnormal rhythms might develop, the patient might suffer great pain and death often occurred rapidly. In 1954, Richard Doll and Bradford Hill reported that there was a high incidence of coronary disease among doctors who smoked, a finding supported a few months later by the American Cancer Society. Its vice-president said that the problems raised by the effects of smoking on the heart and arteries were even more pressing than the more publicised linkage of smoking and lung cancer.67 An association with high fat consumption was also suggested, for populations with the highest consumption also seemed to have the highest death rate from coronary heart disease. The greater incidence in the better-off countries could, however, be due to other factors such as a low level of physical exercise and other features of high standards of living.68

It being an axiom in medicine to rest damaged structures, prolonged immobility was traditional for people with heart attacks. A few specialists, however, suggested that the abrupt and grave nature of the disease, when coupled with long-continued bed rest, devastated the morale of people who had previously been active and healthy. ‘Armchair’ treatment was introduced without any apparent problems.69 Anticoagulation by heparin had been used for deep vein thrombosis since the 1930s, and their value in treating life-threatening pulmonary embolus was beyond dispute. Heparin could be given only by intravenous injection but a family of coumarin derivatives that could be taken by mouth was developed in the 1940s. Control was difficult, and regular estimates had to be made of the ‘clotting time’. In heart attacks, the evidence of their value was weaker, largely based on a trial in New York in which patients were treated or not according to the day of the week on which they were admitted. Although there was less evidence of effectiveness, a vogue developed for their use.70 Cardiac arrest, the ultimate danger in a heart attack, was sometimes treated successfully with a new piece of equipment – the external cardiac defibrillator.71 Cardiac surgical development was an example of how progress in clinical medicine is the result of developments by many workers in many fields. These included cardiac catheterisation, new methods of measurement, studies on the coagulation of blood, hypothermia, perfusion techniques (the heart-lung machine), pacemaking, the use of plastics, new design of instruments and studies of immune reactions.72 It was the development by Magill and Macintosh of endotracheal anaesthesia (in which a mask was replaced by a cuffed tube inserted into the trachea) that made surgery inside the chest practicable. Cardiac catheterisation was devised in Germany in the 1930s but was not commonplace until the 1950s when it became the tool used to explore the right side of the heart, to measure atrial, ventricular and pulmonary artery blood pressures and to take blood samples. Combined with arterial blood sampling, it became possible to determine the nature of heart valve damage, for example, after rheumatic fever. This permitted good case selection and carefully planned heart surgery. Twenty-four-hour electrocardiography was introduced in the USA by Norman Holter, improving the diagnosis of abnormality of heart rhythm.

Progress in England centred on Guy’s, the National Heart Hospital, Leeds and the Hammersmith, and was led by people such as Russell Brock at Guy’s, Cleland at the Hammersmith, and Thomas Holmes Sellors at the Middlesex. The heart operations undertaken before 1948 had included surgery to repair congenital defects that could be undertaken rapidly without stopping the heart or opening it, for example, operation for patent ductus arteriosus (in which a connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery remains open after birth). ‘Blue babies’ with congenital heart disease would seldom outlive their teens without surgery.73 Brock operated on some, but several of his earliest cases died. The coroner was alarmed and Brock had to explain the risks of surgery and the way the children selected for operation were already near the point of death. Unless surgeons could develop the necessary operative techniques, all such patients were doomed. Wartime experience with the treatment of bullet wounds of the heart had given surgeons courage to challenge the long-held belief that operating on the heart was dangerous. It was commonly believed that rheumatic heart disease was a disorder of heart muscle and not primarily due to valve damage. Some surgeons, however, believed that valve damage was the crucial lesion; in 1948 three surgeons, Dwight Harken and Charles Bailey in the USA, and Brock at Guy’s, independently performed successful mitral valvotomy for mitral stenosis, widening the opening of valves that had become partially fused and were restricting blood flow. Brock attempted three operations within a fortnight. The surgeons were entering unknown territory and their work proved that the problem of chronic rheumatic heart disease was primarily mechanical. Brock’s work was followed by Thomas Holmes Sellors at the Middlesex in 1951.74 There was a backlog of seriously sick people in or approaching heart failure. The first operations had a high mortality, seven in the first 20 of Brock’s series. This rapidly improved to about 5 per cent for mitral valvotomy, and more difficult lesions such as pulmonary stenosis were tackled.75 Many of the patients were young men and women doomed to an early death without surgery. Sometimes the type of repair needed was beyond the techniques available. Yet risky though the attempts were, particularly on pulmonary and aortic valves, there was often no alternative.

The introduction of hypothermia in the early 1950s was the next advance. It was found that, at a body temperature of 30°C, the heart could be stopped for ten minutes. The commonest method was immersion in a bath of cold water. It proved possible to repair some atrial septal defects (openings in the division between the two atria) and make an open direct-vision approach to the pulmonary and aortic valves. Hypothermia could also be used in the resection of aortic aneurysms (absence of the aortic valve opening).76 Perfusion came next. The technique of producing temporary cardiac arrest using potassium was worked out by Melrose, a physiologist at the Hammersmith Hospital. Heart-lung machines were developed by the Kirklin unit at the Mayo Clinic in the USA, and in England by Melrose and Cleland at the Hammersmith. There was much to be learned; Kirklin reported six deaths in his first ten cases, and a further six in the next 27. But, by the time he had reached 200 cases, deaths from the procedure were rare.77 British cardiac surgeons deliberately held back and waited to see what the outcome of Kirklin’s work would be. When he had developed reliable procedures, three British units at the Hammersmith, Guy’s and Leeds began work. All were well equipped, well staffed and expertly run departments. A pattern was set; cardiac surgery became established in regional centres, usually in association with a university teaching hospital. Only near such surgical facilities could advanced cardiology develop effectively.

Cardiac arrest was not necessary for operations on large blood vessels such as the aorta. Coarctation of the aorta, in which the vessel became narrowed, and aortic aneurysms also became manageable surgically.78 After the introduction of angiography, in which solutions that were opaque to X-rays were injected into blood vessels, the frequency of atheromatous obstruction of the internal carotid artery was realised. Angiography was an uncomfortable and sometimes hazardous investigation. Urged on by George Pickering, Rob and Eastcott performed the first carotid endarterectomy at St Mary’s Hospital in 1954, on a woman with transient episodes of hemiplegia and difficulty with speech. Although an increasing number of patients were treated, it remained a risky operation.79

Renal replacement therapy

Life-threatening kidney disease might be either acute or chronic. Acute renal failure, from the crush injuries of the blitz, a mismatched blood transfusion or a prolonged low blood pressure from blood loss, might get better if the patient could be kept alive long enough. If great care was taken with fluid intake and diet, some survived. In 1943, it was shown by Kolff in Holland that patients with terminal renal failure could be kept alive by artificial haemodialysis. Few were thought to be suitable for this, and it was mainly used for those in acute renal failure from which spontaneous recovery was to be expected. It was not offered to patients who had an irreversible condition from nephritis associated with streptococcal infection, diabetes or high blood pressure.80 Indeed it was thought unethical to offer dialysis to those with chronic disease, as it would only delay an inevitable and unpleasant death. However, in 1954 a successful renal transplant was undertaken in the USA. The patient, who had chronic renal failure and would otherwise have died, received a kidney from an identical twin. While only one in 100 would have the chance of a sibling’s kidney that the body’s immune system would not reject, asking everyone with chronic renal disease whether he or she was a twin was now important.

Neurology and neurosurgery

The great developments in descriptive neurology and neurosurgery largely preceded the NHS, under the influence of North American surgeons such as Harvey Cushing and Wilder Penfield, and British neurologists such as Francis Walshe. The central nervous system, once damaged, did not regenerate, neither could it be repaired surgically. The specialty centred on the accuracy of diagnosis. Seldom was there any treatment available; only three out of 100 papers published in Brain held out any hope for the patient. Shortly before the NHS started, the RCP committee on neurology, seeing a need to develop the specialty outside London, recommended the development of active neurological centres in all medical teaching centres, in which neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry should work together.81 At least one such centre, in Newcastle, equalled anything in the south. There, Henry Miller was followed by John Walton and David Shaw. Miller, who was interested in immunological disease, pointed out the advantages of the neurologist working in a hospital providing district services, who would see local epidemics, deal with people who were at an early stage of their disease and were often acutely ill, and be in close contact with other physicians.82 Miller, and Ritchie Russell in Oxford who was interested in poliomyelitis, began to reorientate neurology and link it more closely to general medicine. Attitudes began to change, with concentration on the prevention of damage in the first place, altering the biochemistry of the nervous system, and on rehabilitation. Developments elsewhere in medicine, in clinical pharmacology, imaging and later genetics, drove neurology and neurosurgery, which advanced steadily as specialties rather than experiencing sudden and major developments.

In the 1950s, neurosurgery dealt with head injuries, brain tumours, prefrontal leucotomy for mental illness, destruction of the pituitary for advanced cancer of the breast and precise surgery deep in the brain for Parkinson’s disease (stereotaxic surgery). New diagnostic investigations, in particular cerebral arteriography, helped it. Seeing the circulation of the brain was possible by taking a series of radiographs in rapid succession after the injection of contrast medium. Cerebral tumours and intracranial haemorrhage, cerebral aneurysms and cerebral thrombosis were all revealed, making diagnosis more accurate and operation more successful.83

Ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery

Three main developments – antibiotics, better anaesthesia and the introduction of the operating microscope – underpinned advances. Until the introduction of antibiotics, the main function of the ENT surgeon was to save life by treating infection, acute or acute-on-chronic, affecting the middle and inner ear, the mastoids and the sinuses. Untreated infection could spread inside the skull, leading to meningitis and brain abscesses. By 1950 such catastrophic diseases were rare. The work of ENT surgeons altered substantially and those mastoid operations still being carried out were usually for long-standing disease.84

Zeiss produced the first operating microscope specifically for otology in 1953, revolutionising ENT surgery. Surgeons began to turn their attention to the preservation of hearing, the loss of which they had previously accepted as inevitable. Chronic infection of the middle ear prevented the movement of three minute bones that transmitted sound. Some operations that were now popularised had been attempted 50 years previously, but without magnified vision and modern instruments and drills they had been abandoned. Though simple in conception, the operations demanded scrupulously careful technique and great patience.85 Among the first to become widespread was an operation for otosclerosis, to free-up certain small bones in the middle ear (mobilisation of the stapes), or to remove them (stapedectomy). Tympanoplasty (repairing damage to the middle ear) was described in Germany in 1953. Under the influence of surgeons such as Gordon Smyth of Belfast, the procedure was rapidly introduced into the UK.

The commonest ENT operation, indeed the commonest operation, was ‘tonsils and adenoids’ (Ts and As). Surgeons seemed most convinced of the benefits, whereas the MRC regarded the procedure as a prophylactic ritual carried out for no particular reason and with no particular result. John Fry, a Beckenham GP, in a careful analysis of his patients, concluded that although nearly 200,000 operations were carried out annually, the number could be reduced by at least two-thirds without serious consequences. Operation was usually carried out for recurrent respiratory infections, problems that tended to natural cure at around the age of seven or eight. The operative rates seemed to depend entirely on local medical opinion. A child in Enfield was 20 times as likely to have an operation as one in nearby Hornsey; the children of the well-to-do were most at risk of operation.86 From the mid-1940s there was dramatic growth in the incidence, or recognition, of ‘glue ear’ in children, a condition that made them deaf. Thick gluey mucus remained in the middle ear, usually after upper respiratory tract infections. It was uncertain whether this was related to the widespread use of antibiotics, but an operation for inserting a grommet through the eardrum after removing the mucus by suction succeeded Ts and As as the commonest operation worldwide.

In the non-surgical field, the MRC had designed a hearing aid shortly before the NHS began, the Medresco aid. It was developed by the Post Office Engineering Research Station at Dollis Hill, assembled by a number of radio manufacturers instead of the hearing aid industry, and issued free of charge on the recommendation of a consultant otologist. The market was a large one, but the Medresco aid, though cheap, was behind the times. It consisted of a body-worn receiver connected to an ear-piece. Transistors, incorporated into commercial aids from 1953, were not used in the aids issued free by the NHS until several years later.

Ophthalmology