Chronology: the third decade

1968

Background

Czechoslovakia uprising

Moon orbited

NHS events

Ministry of Health and Ministry of Social Security form

Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) – Richard Crossman, Secretary of State

Hong Kong influenza epidemic

Royal Commission on Medical Education (Todd)

Seebohm Report

First Green Paper on NHS Reorganisation

Designation of regional hospital board (RHB) hospitals for medical education

Prices and Incomes Board no. 60 on Nurses

Heart transplants

Royal College of Nursing (RCN) admits student nurses

1969

Background

Man on the moon

Age of Majority reduced from 21 to 18

British troops in Northern Ireland

Woodstock

Boeing 747 in service

NHS events

Bonham-Carter Functions of the DGH

Ely Hospital report published

Hospital advisory service

Royal Commission on Local Government

1970

Background

Conservative government (Edward Heath)

Simon and Garfunkel ‘Bridge over troubled water'

Alvin Toffler’s Future shock

NHS events

Second Green Paper on NHS Reorganisation

Peel Report on domiciliary midwifery and maternity bed needs

RCN pay campaign; admits State Enrolled Nurses (SENs) and pupil nurses

1971

Background

Decimalisation of currency

Increase in pop music festivals

NHS events

Consultation on NHS reorganisation

Briggs (Nursing)

Coronary artery bypass surgery

Better services for the mentally handicapped

Harvard-Davies ‘Organisation of Group Practice’

1972

Background

Watergate burglary

‘Bloody Sunday’

NHS events

NHS Reorganisation White Paper

Ancillary staff on strike

Hunter on Medical Administrators

‘Grey Book’ on Management arrangements for the reorganised NHS

Computerised tomography (CT)

Faculty of Community Medicine formed

1973

Background

Yom Kippur war; OPEC rise in oil price

Publication of Small is Beautiful

School leaving age raised to 16

UK joins EEC

Miners’ strike

Ancillary staff in hospital strike

NHS events

NHS Reorganisation Act

Health Service Commissioner

Accounting for health (King’s Fund Report)

1974

Background

Three-day working week

February election: minority Labour government

October election: Labour government with majority of three

Microsoft established

Aerosols reported as depleting ozone layer

NHS events

NHS reorganisation

Control of Pollution Act

Consultant industrial action over private practice

Democracy in the NHS

Halsbury Committee on pay and conditions of nurses and professions supplementary to medicine (30 per cent rise)

Lalonde on health promotion

Health and Safety at Work etc. Act

1975

Background

First North Sea oil

Peak inflation 26.9%

US withdrawal from Vietnam

NHS events

NHS Planning System

Whole body CT scanning

Moorgate Tube disaster

Controversy over pay beds

Merrison: Regulation of the Medical Profession

Better services for the mentally ill: White Paper

London Coordinating Committee

1976

Background

International Monetary Fund Loan

Concorde in service

James Callaghan Prime Minister

NHS events

Health Services Board (private practice)

Priorities for health and personal social services

Royal Commission on NHS established

The NHS Planning System

Sharing resources for health in England (the RAWP report)

Legislation for mandatory GP vocational training (from 1982)

Normansfield mental handicap hospital scandal

Prevention and health: everybody’s business

Fit for the future (Court Report on child health)

Cimetidine for stomach ulcers

UK Colleges’ criteria for brain-stem death

Hospital Advisory Service becomes Health Advisory Service

1977

Background

NHS events

The way forward (Priorities for the NHS)

Health for All by 2000 declaration

London Health Planning Consortium

Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre formed

Twenty years on

The 1960s had started with optimism, austerity had ended, economic growth seemed assured, poverty was receding and life was improving. From 1964 the situation deteriorated as the international balance of trade swung against the UK and long-range economic forecasts proved wrong. There was severe deflation in 1966, devaluation of the pound in 1967, and the third decade of the NHS began in financial crisis. The time had come to rethink the pattern of the NHS. Alvin Toffler’s book Future Shock described the shattering stress and disorientation induced in people experiencing too much change in too short a time. Clinical development and activity was certainly increasing inexorably.1 There had been few organisational changes in the first 20 years of the NHS which was ‘administered’, rather than ‘managed’. Resources had been tight and there were many service problems to be resolved. Central planning was in vogue and solutions were now sought in changing the management and structure of organisations. Small was not considered beautiful and there was a deep belief in the wisdom of management consultants. The arguments and assumptions about the NHS were changing. No longer was it merely a question of whether the nation could afford a health service, and what form of cost control was required. New questions required a more political solution. Were the resources of the NHS correctly deployed, north and south, and between acute and chronic care? What form of management was appropriate? What were the implications of community care? Should the education of doctors and nurses be matched less to acute disease and more to longer-term needs? Was there too great a disparity in the income of the high earners in the NHS and the ancillary staff? What was the place of private practice? How far should union power extend?

The future relationship of health and local authority services became a key issue. The closely related reports of the Royal Commission on Local Government and the Committee on the Provision of Personal Social Services (Seebohm) appeared. Seebohm recommended bringing together all personnel concerned with any aspect of personal social care into new social services departments within major local authorities. It argued for ‘generic’ social workers, which meant the transfer of highly skilled medical social workers from the hospitals to the local authorities and the destruction of bridges that were being developed between social workers and doctors.2 At the close of 1967, Kenneth Robinson, the Minister, had announced that the government’s views on the structure of the NHS would be set out in a Green Paper. After 20 years, said the British Medical Journal (BMJ), the structure was out of date, but at least modernisation and reform might be in sight. There had been widespread demand for a new service designed to meet the requirements of modern medicine. Delay in making the necessary changes had been a major cause of the emigration of medical people. The whole welfare state, and not just the NHS, needed to be recast for the changing needs of the community. The BMJ concluded that the integration of the management and financing of the NHS was necessary.3

The future relationship of health and local authority services became a key issue. The closely related reports of the Royal Commission on Local Government and the Committee on the Provision of Personal Social Services (Seebohm) appeared. Seebohm recommended bringing together all personnel concerned with any aspect of personal social care into new social services departments within major local authorities. It argued for ‘generic’ social workers, which meant the transfer of highly skilled medical social workers from the hospitals to the local authorities and the destruction of bridges that were being developed between social workers and doctors.2 At the close of 1967, Kenneth Robinson, the Minister, had announced that the government’s views on the structure of the NHS would be set out in a Green Paper. After 20 years, said the British Medical Journal (BMJ), the structure was out of date, but at least modernisation and reform might be in sight. There had been widespread demand for a new service designed to meet the requirements of modern medicine. Delay in making the necessary changes had been a major cause of the emigration of medical people. The whole welfare state, and not just the NHS, needed to be recast for the changing needs of the community. The BMJ concluded that the integration of the management and financing of the NHS was necessary.3

Challenges for the future

Kenneth Robinson chaired a conference to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the inception of the service in 1948. Jennie Lee, Aneurin Bevan’s widow, opened it.4 Bevan, she said, believed that local government could not have coped with the establishment of a health service in 1948 along with all its other responsibilities. The acceptance by the state of total responsibility for a comprehensive health service for everyone was an essential first step. Nevertheless, Bevan had seen that a time might come when the relationship between health and local government would need re-examination, particularly if the units of local government were to become larger.

At the conference, Professor John Butterfield, a physician from Guy’s Hospital, traced the way patterns of disease and health care had changed. The population had increased by 10 per cent and was better housed. Technological advance had taken place, with developments in electronics and laboratory automation and an explosion in the number of drugs available. Acute and infectious diseases were on the wane, but disability caused by chronic and degenerative and debilitating diseases was increasing. John Reid, the Medical Officer of Health (MOH) for Buckinghamshire, talked of the growing interest in medical care in the community, and the development of group general practice with the attachment of local authority health visitors, social workers, nurses, midwives and auxiliaries. Artificial barriers between the three parts of the service were being removed. Henry Yellowlees, Deputy Chief Medical Officer at the Department of Health, spoke of planning and information, and the effects of different medical policies on the use of resources. JOF Davies, the Oxford Regional Hospital Board’s senior administrative medical officer (SAMO), said that reviewing clinical performance and taking advantage of operational research and statistics was important. Desmond Bonham-Carter, Chairman of the Board at University College Hospital, looked at personnel issues. Some people had suggested that the health service was on the verge of general management following an industrial model. General managers would then have authority over medical and nursing directors. His view was that, even if such a manager were paid more than leading consultants and top posts were open to all, a general manager would be unable to dictate to medical, nursing and other disciplines, because their decisions depended on clinical and professional judgements. Trades union representatives raised the need to value the many skills required in the NHS; the problem of recruiting, training and retaining staff; the problems of a tripartite service; and ensuring involvement of the staff side in proposals for change. The unions saw increasing government involvement in negotiations on pay and conditions of service, incomes policies and the pursuit of productivity. They did not believe that any change of government in the next 20 years would alter this fundamentally, because government was increasingly involved in the national economy.5

Much of the agenda for the next decade had been outlined. “Forward into the 1970s,” said Kenneth Robinson, closing the conference. An economic crisis in January 1968 again forced the government to cut public expenditure. Faced with the alternative of reducing hospital building or re-imposing prescription charges, Labour maintained the building programme and introduced a charge of 2s 6d (12.5p) per item, with certain categories of patient exempted.

Medical progress

Health promotion

People were living longer and the major causes of death were changing. Public health measures needed a new perspective. On 10 September 1973, Marc Lalonde, the Canadian Minister of National Health and Welfare, addressed the PanAmerican Health Organization conference in Ottawa. His talk, subsequent working papers and a report published the following year, modestly claimed to unfold a new perspective on the health of Canadians and to thereby stimulate interest and discussion on future health programmes for Canada. The report focused attention on four main factors: human biology, environment, life style and the organisation of health care. Much premature death and disability was preventable.6 Some hypotheses might be sufficiently valid to warrant taking positive action. Being slim was better than being fat; it was better not to smoke cigarettes; alcohol was a danger to health, particularly when driving a car; and the less-polluted air and water were, the healthier we were. The report received international acclaim and led to publications in the USA, Australia and the UK. In November 1975, in response to concern about the disparity of spending on curative as opposed to preventive services, a parliamentary subcommittee began a special inquiry into preventive medicine. David Owen, then Minister of Health, wished that a major effort to bring health promotion to the forefront of NHS through the planning system would mark his time in the Department. In 1976, the government published Prevention and health: everybody’s business.7 The main killer diseases – coronary heart disease, lung cancer and bronchitis – were largely caused by people’s behaviour. Both individuals and government must accept responsibility for health. Cigarette smoking, lack of exercise, the fats in the diet, and obesity were part of the life style of advanced, urban, industrial high-consumption societies. The various government publications sparked debate, for resources were limited and had to be focused on where they would do most good. Some saw the accent on life styles as only half the story, blaming the victim instead of dealing with underlying socio-economic factors affecting health. Government accepted that it had a role to play through fiscal policy, environmental controls, education and housing. But, as there was a class gradient in diet, exercise and smoking, had not the trades unions a role as well?8 Government could not move too far ahead of public opinion, but no single measure would have done more to prevent disease than making tobacco and alcohol progressively more expensive – instead of cheaper – in terms of the labour required to buy them, save perhaps the prohibition of advertising of tobacco. In April 1977, shortly before the 30th anniversary of the NHS, David Ennals, Secretary of State for Social Services in the Callaghan administration, commissioned a review of the available information about differences in health status between the social classes, the possible causes, the implications for policy, and the further research required. Sir Douglas Black, Professor of Medicine in Manchester, chaired the review and was helped by CS Smith, Secretary of the Social Science Research Council, Professor JN Morris, Director of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Social Medicine Unit, and Professor Peter Townsend, from Essex University.

Causes of increased mortality 1968–1978

|

Cause of death |

% increase |

Cause of increase |

|

Cancer of the oesophagus |

12 |

Alcohol |

|

Cancer of the lung |

48 |

Cigarettes |

|

Cancer of the pleura |

43 |

Asbestos |

|

Cancer of the breast |

11 |

? |

|

Cancer of the cervix |

59 |

Multiplicity of sexual partners |

|

Skin melanoma |

37 |

Partly UV light |

|

Alcoholism |

141 |

Alcohol |

|

Drug dependence |

263 |

Addictive drugs |

|

Cirrhosis of the liver |

54 |

Alcohol |

|

Motorcycle accidents |

58 |

Motorcycles |

Source: R Doll (1983)9

Although everyone eventually succumbs to one condition or another, it was commonly argued that redistributing funds in favour of prevention could reduce the burden of disease and the cost of the NHS. A series of reports from the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) on smoking, atmospheric pollution, fluoridation, dietary fibre and coronary thrombosis had encouraged interest in prevention. Health promotion, Richard Doll argued, was primarily about the identification of measures proven to prevent the onset of disease, implementing them and measuring what was achieved. Many diseases that were increasingly taking their toll were amenable to prevention, in particular, cancer of the lung and heart disease. Prevention of trauma had been successful; in spite of the enormously increased number of vehicles and the rise in population, a series of regulations had held deaths on the road to around 6,000 per year for the past 50 years. Sometimes the public would resist a measure that would reduce the toll of disease greatly, while pressing for action that would not only be costly but also produce minimal benefits.10

The contribution of acute medicine to health

Thomas McKeown believed there had been undue concentration on acute medicine and the hospital services. He disagreed with the idea that improvement in health must be based on understanding the structure and function of the body and the processes of disease. At a symposium in 1970, and in his Rock Carling monograph of 1976, he examined the causes of death, the reasons for improvement in human health over the past two centuries, and the parallel development of medical science and the hospitals.11 He thought that past improvement had mainly been due to changes in behaviour and the environment, better food, cleaner water and an improved standard of living. One must look to these for further improvement. He thought that medical science and medical services were misdirected. Society’s investment in health was not well used because it rested on a false assumption about the basis of human health. It was assumed that the body was a machine whose protection from disease and its effects depended primarily on intervention. The patient’s demand for acute care and the physician’s wish to provide it were the result. The requirements for health were simple: to be born healthy, to be adequately fed, to be protected from a wide range of hazards in the environment, and not to depart radically from the pattern of personal behaviour under which people evolved by smoking, over-eating or leading a sedentary life. Environmental change, personal preventive measures and therapeutic intervention had to be brought together.12 It was a critique echoed by others. McKeown’s conclusion, that until the beginning of the twentieth century, it was unlikely that immunisation or therapy had a significant effect on the mortality of the population, was a foundation of what became known as ‘the new public health’.

McKeown played down the contribution of clinical medicine. He hunted for evidence for his theory, ignoring the dubious nature of statistics a century old. Henry Miller, the neurologist, now Vice-Chancellor of Newcastle University, believed that public health doctors in general discounted the clinician’s contribution because much of medicine was aimed at the reduction of suffering and the improvement of function, and it was hard to identify a substantial impact on mortality rates.13 During the previous 30 years, clinical medicine had been transformed – the conquest of poliomyelitis and syphilis being examples. An effective accident service would also make a major contribution to public health. Miller had no doubt that the hospital system would survive as the functional and intellectual hub of the NHS. Julian Tudor Hart, a GP at Glyncorrwg in Glamorgan deeply committed to a socialist analysis of society, also thought clinical medicine helped people, but he thought that resources were distributed in an inefficient way. In his article, ‘The inverse care law’, published in The Lancet, he said that the availability of good medical care tended to vary inversely with the need of the population served. Those doctors most able to choose went to work in middle-class areas. Places with the highest mortality and morbidity got the rest – often doctors from abroad who had difficulty obtaining the most sought-after jobs. In the areas with the most sickness and death, GPs had more work, larger lists, less hospital support and ‘traditional’ but ineffective ways of working. The hospital doctors in these areas shouldered heavier caseloads with fewer staff and less equipment, more obsolete buildings and a shortage of beds. Tudor Hart was worried by calls on the right for a return to an insurance-based system and the marketplace. He believed that the NHS had brought a substantial improvement in access to health care for those previously deprived, chiefly as a result of the decision to remove the NHS from market forces.14

The quality and effectiveness of health care

Archibald Cochrane’s Effectiveness and efficiency stimulated much thought. Quality was a major theme underlying many aspects of health care rather than an isolated topic of its own, and was the topic of a Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust symposium.15 The direction of the quality movement in health care was affected by the country’s social and economic culture. In the UK, the NHS tended to insulate people from the need to consider costs and quality together.16 In the USA, rising costs led to the introduction of ‘utilisation review’ and a demand for more information about costs and quality. Professional Standards Review Organisations (PSROs) were introduced in 1972. Money went into research projects. Dr RH Brook and his colleagues at Baltimore City Hospital, evaluated the quality of care of patients treated for urinary tract infection, uncontrolled hypertension and ulcers, all conditions in which it was relatively easy to define adequate investigation, treatment and follow-up.17 They found a wide variation in quality. David Rutstein, at Harvard, suggested that the occurrence of an unnecessary disease, disability or untimely death was a sentinel event requiring search for remediable underlying causes. He believed that such an approach could be used more widely than deaths in childbirth or during surgery.18 Avedis Donabedian, an American academic and perhaps the most influential theorist in the field of quality assurance in health care, provided a framework that clarified thinking.19 Quality could be looked at from three standpoints:

|

Structure |

The adequacy of facilities and equipment, the qualifications of the medical staff and their organisation, ‘proper’ settings for health care |

|

Process |

Whether what was thought to be ‘good’ care was given, the appropriateness and completeness of the history and examination, justifiable diagnosis and therapy, co-ordination and continuity of care |

|

Outcome |

What the result was in terms of patient satisfaction, quality of life, illness and death (morbidity and mortality) |

Two features, said the BMJ, must underlie any worthwhile system of medical audit: first it must be effective, and second, it must be totally independent of the state. That said, the profession should not only be concerned about its standards but also be seen to be.20 The Maternal Mortality inquiry was an example of an outcome study that revealed problems with the structure and processes of care. Disquiet at the conditions in long-stay hospitals had led to reviews. Surgeons took an increasing interest in their results.21 A call for the widening of audit came from doctors and public alike, and increasingly it was felt that people had the right to reassurance that there was monitoring of clinical standards, as there was in education and child care. Audit systems were developed. A standard of care, perhaps based on published research work, would be established. Professional activity would be compared with the standard, and the results of the evaluation used to modify clinical conduct. The audit might be conducted by the professionals themselves or by an external agency.

Enquiries into the structure, the processes and the outcome of care revealed that resources were not always used to the best purpose. In 1969, the British Medical Association (BMA) Planning Unit drew attention to the unaccountable variations in the frequency of some routine operations from city to city and hospital to hospital, in the mortality from standard surgical procedures, and the duration of stay in hospital of patients with similar diseases. Did patients with hernias or varicose veins who stayed in hospital a couple of weeks really do better than short-stay or outpatient cases? Did patients with coronary heart disease do better under continuous monitoring in hospital or at home with simple nursing care? At what point did population screening cease to pay dividends and become counterproductive? Such questions required answers that could only come from the professions; a government department could not furnish them.22 The Planning Unit also considered the complex and expensive forms of treatment being introduced, in particular organ transplantation. Some argued that these should be discouraged, in the dubious expectation that this would in some way lead to improvement in the quantity or quality of existing services. The Planning Unit thought that to slow research activity would be incompatible with professional freedom and with the enterprise expected of NHS staff.

The interests of staff and public might conflict; the medical profession was prepared to consider quality within an educational framework. People who had reason to question the quality of the care they had received looked for something with more bite. In 1976 there were 17,000 complaints about hospital treatment, one for every 300 patients admitted. Hospitals, said the BMJ, should have a simple system for handling complaints. But care was needed – the medical profession was beginning to look at ways of improving standards through voluntary medical audit, and an open-ended complaints procedure including matters of clinical judgement might postpone audit for another generation.23 In any case, financial problems were also a threat to quality. At a BMA Council meeting, Dr Appleyard, a paediatrician, said that the profession should tell Mr Ennals (then the Secretary of State) that it was no longer prepared to cover up the inadequacies of the health service. What was the position of a consultant who decided that staffing levels were insufficient and patients were at risk? A small group of the Joint Consultants Committee was appointed to consider a way to identify hospitals that were becoming dangerous to patients.24

A parliamentary commissioner on administration (ombudsman) had been appointed in the late 1960s, and the parliamentary select committee reporting in 1971 recommended the inclusion within his remit of complaints about hospitals.25 The medical profession had no objection to complaints about the failure of an ambulance to arrive or the squalid condition of a casualty department. The difficulty arose, however, if a patient died and relatives thought he might have survived had the treatment been different – a matter that could already be pursued through the courts. The Health Service Commissioner, Sir Alan Marre, opened his doors in October 1973, and there were several no-go areas. Patients who had appealed to a tribunal or had gone to court, or had the right to do so, normally could not take their grievance to the Commissioner. Neither were actions that were the result of clinical judgement included.26

Changes in society

Changes in life style were affecting health and the health service. Overseas package holidays became widely available, skiing became more popular, and eating patterns altered. Increased car ownership altered leisure activities; exercise became fashionable and aerobics was introduced. The Woodstock festival was held in 1969; the young were urged to “turn on, tune in and drop out”. The following year, a festival on the Isle of Wight attracted 200,000 people over a period of a few days. As nobody knew how many would come, the catering and sanitary facilities were strained. Festivals became a regular occurrence and initially there was much goodwill, although the personal conduct of those attending attracted media interest. Local doctors and voluntary organisations gave their time generously and little drug misuse was apparent. Those attending were said to have a natural dignity, grace and happiness that were difficult to credit unless seen.27 The BMJ was less enthusiastic.28

If the festivals are not the degraded orgies that they are sometimes made out to be, nor are they quite the care-free wandervögel, healthful communing with nature that their admirers have occasionally supposed. They are commercial ventures which can succeed financially or fail, and the people who attend them pay for their entertainment – apart from the considerable number of gate crashers. A fully satisfactory public health service for the occasion should therefore be included in the cost of it.

Advances in technology

Ever more complex diagnostic techniques, multitudes of drugs, and highly complex surgery were changing the face of medical practice. Sub-specialisation increased. Some orthopaedic surgeons tended to deal with fractures, others with joint replacement. Increasingly, the treatment of a single patient required the co-operation of different specialties, as in the case of cardiac and pulmonary resuscitation, renal dialysis and transplantation. Medical laboratory work was expanding. Computers, initially linked to analytical equipment, were increasingly built into laboratory systems. The fibreoptic endoscopes, developed in Japan by Olympus and other companies, could now be used to look at the oesophagus, stomach, duodenum and colon, and to take samples for pathological examination (histology and cytology).29 ‘Spare-part’ surgery was growing, as metal, plastic or dead tissues were used to replace parts of the body with a relatively inert mechanical function, such as arteries, valves and joints. Transplants were increasingly successful.30 Most acute hospitals had intensive care units, where patients who had had heart attacks could be continually monitored by nurses watching electrocardiogram (ECG) displays, and resuscitated when necessary.31 No wonder, wrote a physician, that sympathy seemed less of a priority, for doctors were human and there was a limit to the capacity to absorb and transmit all this and sympathy too. Reversion to the gentler manner of a bygone age seemed unlikely.32

The drug treatment of disease

Genetic engineering slowly began to influence the development of new drugs. Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer at Stanford University combined their knowledge of enzymes and DNA, and in 1973 published a method of inserting foreign genetic material into bacterial plasmids.33 The Cohen-Boyer patent, which earned Stanford an ever-increasing amount ($15 million in 1995), was one of the first steps in developing recombinant techniques.

In spite of the many new antibiotics, ward infections by strains that were difficult to treat became more common.34 The drugs that remained effective had to be used with caution and in the knowledge of the changing patterns of resistance. During the 1950s, staphylococci were increasingly found to produce penicillinase that inactivated the antibiotic. The production of penicillinase-stable penicillins such as methicillin gave clinicians a temporary respite, but then methicillin-resistant strains appeared. It seemed as if the main classes of antibiotics had now been identified, and henceforth discoveries were little more than additional members of an existing group.

The traditional treatment of stomach and duodenal ulcer had been based on diet, alkalis and, if these failed, surgery (partial gastrectomy or vagotomy and drainage). Relapse after medical treatment was almost invariable and recurrence after surgery was common.35 Now there was a new answer. Histamine had long been known to stimulate gastric acid secretion but antihistamine drugs did not relieve ulcer symptoms. In 1964, James Black examined several hundred chemicals with a slightly different pharmacological action and found some that did reduce gastric acid secretion. The first compounds to be tried were not effective by mouth, or had unacceptable side effects. However, in 1976 cimetidine, and later ranitidine, which required fewer daily doses, proved a breakthrough, helping duodenal and gastric ulcers to heal. They were so effective, and adverse reactions so few, that some GPs – instead of waiting for X-ray examinations – made a diagnosis by seeing if the new drugs gave relief. Long-term administration seemed necessary, which helped these drugs become the first products to generate US$1 billion revenue.36

Advances also occurred in the treatment of asthma. An entirely new agent was introduced – disodium cromoglycate (Intal) – which inhibited a bronchial reaction to inhaled allergens. It was best used as prophylaxis by regular administration of the dry powder in a special inhaler. Better bronchodilators, which made breathing easier, became available. For example, salbutamol partly replaced isoprenaline, which had been used for many years.37 The treatment of high blood pressure was also improved. Many people could not tolerate the side effects of the earlier drugs, but the introduction of beta-receptor blocking drugs (such as propranolol in 1969) that were effective and easier to take improved compliance.38 In 1974, Peter Ellwood and collaborators at the MRC Epidemiology Unit in Cardiff published a paper on the possible use of aspirin to prevent myocardial infarction; the result was suggestive but statistically inconclusive.39

The ‘non-steroidal anti-inflammatory’ drugs were a major advance in the management of arthritis. Aspirin, the mainstay of treatment, was a discovery of the nineteenth century chemical industry. In the 1950s, alternatives such as phenylbutazone became available, followed in the 1960s by other drugs including indomethacin, and a range of propionic acid derivatives including ibuprofen and naproxen.40 The way in which they relieved symptoms remained a mystery until 1971, when John Vane offered an explanation of their activity in blocking prostaglandin synthesis and release. Parkinson’s disease was also helped by the introduction of levodopa in 1970.

By 1968, a million women were on the contraceptive pill, and there was growing concern about its side effects. A strong relationship was reported between the use of the pill and death from pulmonary embolus or cerebral thrombosis (a stroke caused by a clot forming in a major artery to the brain).41 The Committee on Safety of Drugs recommended the use of low-dose preparations. The thalidomide disaster of 1961 was casting a long shadow. Manufacturers now had an entirely rational fear of adverse publicity and expensive litigation, and might only undertake costly research and testing on drugs that had a potentially large market.42

Misuse of drugs steadily increased. There were few, if any, valid indications for the use of amphetamines, but the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry was opposed to a ban. Several groups of doctors, including the Inner London Medical Committee, overrode the industry and recommended a prohibition of their use.43 Barbiturate abuse was also common. Young addicts found them lying around the home, and sometimes stole prescription pads from surgeries or burgled pharmacies. A campaign to restrict their use was also launched; benzodiazepines were just as effective and their addictive properties still seemed low.44

Drug interaction and ‘bioavailability’, the extent to which a product administered can be used by the body, became important. Digitalis had been one of the few effective cardiovascular drugs, although determining the ideal dose for an individual patient had always been difficult. It became possible in 1968 to measure plasma concentrations accurately by tests using radio-isotopes (radio-immune assay). The research workers developing the technique were the first to notice that batches of digoxin manufactured after May 1972 produced twice the previous plasma levels, although the tablets had the same content. What had changed was the formulation, the fillers, buffers and stabilisers used. A warning was immediately issued about this first major example of a bioavailability problem. Drugs might interact with each other. Anticoagulants had been used widely in the treatment of heart attacks. However, careful control was needed. Indomethacin, salicylates and sulphonamides enhanced their effect; sedatives and tranquillisers might inactivate them.45

The pattern of suicide changed. Suicide from coal gas and barbiturate poisoning had been common but became less so, because natural gas had a lower carbon monoxide concentration and barbiturates were less commonly prescribed. Potential suicides chose from the ever-widening range of sedatives, tranquillisers and antidepressants; suicide from prescribed drugs increased.46 Accidental overdosage could also occur, particularly in children, so protective packaging began to be introduced. Even coffee had hazards; too much produced symptoms indistinguishable from those of anxiety neuroses. Sudden withdrawal might also produce severe headaches. To what could one turn for relief?47

Radiology and diagnostic imaging

Advances in surgical treatment imposed new diagnostic demands on X-ray departments – for example, a series of pictures in rapid succession to give a moving image. More films meant more radiation and greater risks for both patients and staff. However, it became possible to cut radiation exposure by three-quarters when rare earth intensification screens, which produced a brighter image, were introduced. Simultaneously, new contrast media were introduced that were safer and less unpleasant for the patient. Image intensifiers were developed further and produced clearer and more detailed images. Coupled to TV systems and cine equipment, they were rapidly applied to studies of the oesophagus, gut and heart. Because images could be recorded in digital form, they could be compared and manipulated using the ever-increasing computer power that was becoming available.

Sometimes new methods of producing pictures did not use X-rays. Another name was therefore found for X-ray departments – diagnostic imaging. Radio-isotope imaging systems were becoming better and gamma cameras were increasing in efficiency. Unlike rectilinear scanners, they could detect radiation all over the area being examined at the same time, so they were quicker in use and could show radio-isotopes moving from one part of an organ to another. Ultrasound was widely available and the quality of sensors and computing improved rapidly. Moving images could now be seen using ‘real-time’ ultrasound, and the newer scanners were smaller, easier to install and easier to use. Already widely used in obstetrics, cardiology also benefited. Blood flow and valve movement could be measured as new techniques were used, such as the Doppler effect.

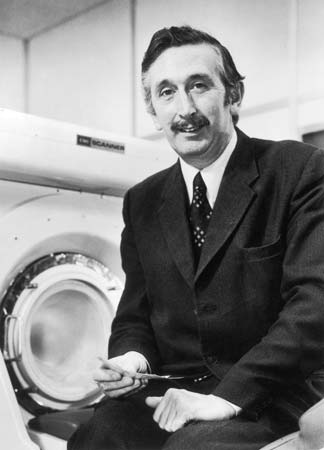

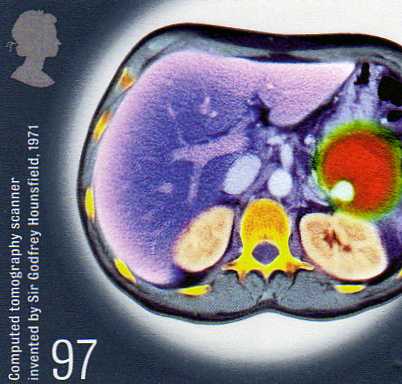

The most important advance of the decade was the introduction of X-ray computed tomography (CT). Since the first x-rays in 1895, all radiographs had shared the same constraint – a two-dimensional image. The limit on progress was thought to lie in the systems producing radiation. Now orthodoxy was challenged. Interest shifted from the source of the radiation to the detection of the image. Advances in detection, combined with a finely collimated beam, allowed a 1,000-fold increase in the power of systems. Godfrey Hounsfield, an engineer at EMI (Electrical Musical Industries), announced the development of X-ray computed tomography at the British Institute of Radiology Congress in 1972.

The most important advance of the decade was the introduction of X-ray computed tomography (CT). Since the first x-rays in 1895, all radiographs had shared the same constraint – a two-dimensional image. The limit on progress was thought to lie in the systems producing radiation. Now orthodoxy was challenged. Interest shifted from the source of the radiation to the detection of the image. Advances in detection, combined with a finely collimated beam, allowed a 1,000-fold increase in the power of systems. Godfrey Hounsfield, an engineer at EMI (Electrical Musical Industries), announced the development of X-ray computed tomography at the British Institute of Radiology Congress in 1972.

Hounsfield modestly wrote that the technique of CT scanning might open up a new chapter in X-ray diagnosis. Tissues of near similar density could be separated and a picture of soft-tissue structure within the skull or body could be built up. It was a fundamental advance in diagnostic medicine. Instead of film, X-rays registered on sensitive crystal detectors. The patient was scanned by a narrow beam that was moved across the body and also rotated around it. A huge number of readings were fed into a computer that mathematically worked out the values of density of each ‘pixel’ of the image. It displayed cross-sectional images in an entirely new way.48 Ian Isherwood, Professor of Diagnostic Radiology at the Manchester Royal Infirmary, said the new process opened the brain of the patient and the mind of the doctor.49 One could not only look at an image but could also formulate questions to ask of it.

Hounsfield modestly wrote that the technique of CT scanning might open up a new chapter in X-ray diagnosis. Tissues of near similar density could be separated and a picture of soft-tissue structure within the skull or body could be built up. It was a fundamental advance in diagnostic medicine. Instead of film, X-rays registered on sensitive crystal detectors. The patient was scanned by a narrow beam that was moved across the body and also rotated around it. A huge number of readings were fed into a computer that mathematically worked out the values of density of each ‘pixel’ of the image. It displayed cross-sectional images in an entirely new way.48 Ian Isherwood, Professor of Diagnostic Radiology at the Manchester Royal Infirmary, said the new process opened the brain of the patient and the mind of the doctor.49 One could not only look at an image but could also formulate questions to ask of it.

Hounsfield worked with Dr James Ambrose, at the nearby neurosurgical unit at Atkinson Morley’s Hospital where the earliest clinical images were created. On 1 October 1971, Ambrose made medical history by carrying out the first CT scan on a live patient, revealing a detailed image of a brain tumour. It was the improvement of computer processing that made the early scans possible, but 15 minutes of computing was needed to create a single picture. Hounsfield recognised its significance in radiology but was unable to interest his company in its development; EMI was more used to marketing the Beatles’ music and did not have the infrastructure to support major medical instrumentation. Visiting radiologists understood the potential and Ian Isherwood encouraged the Department of Health to support the new technology. The Department funded the development of a head scanner and the second prototype was installed in 1971 at the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases, Queen Square. The development was commemorated on a postage stamp in 2010.

Scanners revolutionised the diagnosis of stroke and intracranial haemorrhage (bleeding within the skull). At first the new technique was used only by neurologists because the part being scanned had to be surrounded by a water jacket and remain completely still. Normal structures of the brain were beautifully shown, and the position and nature of space-occupying lesions could be seen with great accuracy.50 The scanner that neurologists required was small and the images were so good that they rapidly displaced older examinations such as cerebral arteriograms and air encephalograms that were painful and risky. With the development of larger whole-body scanners in 1975, first used by Louis Kreel of Northwick Park, the results (particularly from scanning the chest and pelvis) opened new diagnostic possibilities.51 International interest in the new technology was keen and firms based outside Great Britain with long experience in radiology (such as Philips and Siemens) developed new generations of equipment. CT scanning, unknown at the beginning of the decade, was an ambition of every district general hospital (DGH) by its end. Initially introduced to regional and neurological centres, many DGHs began to appeal for charitable funds, even though each scanner carried with it high running costs. The images from the new techniques were digital and it became possible to record digital images from conventional X-ray equipment. Magnetic disks could now store them, opening the possibility of doing away with a silver-based photographic process.52

Interventional radiology

The trend in diagnostic imaging had been towards less-invasive procedures, yet imaging and surgery began to converge as a new sub-specialty, ‘interventional radiology’, developed. Image intensifiers allowed radiologists to work in normal room lighting. The improved ability to pass fine catheters along blood vessels into the smallest branches, and to see precisely where they were, meant that it was possible for radiologists to carry out quasi-surgical procedures under radiographic control. Interventional radiology became the umbrella term covering many therapeutic and diagnostic procedures. Catheters could be manipulated to reach most parts of the body, and a wide range of lesions could be treated. The principal techniques were the obliteration of abnormal blood vessels such as angiomas with materials including gel-foam or polyvinyl alcohol foam, increasing blood flow in narrowed vessels, and dissolving blockages formed by thrombosis with clot-dissolving agents.53

Infectious disease and immunisation

Communicable diseases could still produce a surprise. What was true of one microbe, said James Howie, Director of the Public Health Laboratory Service (PHLS), was not necessarily any guide to the life style of another. The diseases displayed the versatility of the microbes that caused them.54 Viruses were generally associated with acute illnesses; now evidence was accumulating that they were also responsible for a variety of subacute or chronic degenerative conditions such as Creuztfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), and two diseases in animals, scrapie in sheep and mink encephalopathy.55 Though rare, the extraordinary nature of their agents that were highly resistant to normal methods of sterilisation made them of interest.

Countermeasures could be developed only by slow and often tedious methods. There were three main methods of control: immunisation, hygiene and chemotherapy. Immunisation had substantially reduced the common diseases of childhood. Measles immunisation became public policy in 1968, but the levels of cover were often disappointing. For whooping cough there had usually been more than 100,000 notifications a year before immunisation was introduced in the 1950s. This had fallen to around 2,400 by 1973 when the vaccination rate was over 80 per cent. In 1974/5 public concern followed presentation of data about the problem of neurological complications associated with immunisation. Cover fell from 80 per cent to 30 per cent, and major epidemics of whooping cough followed in 1977–1979 and 1981–1983. It took ten years for balance to be restored.

From 1968/9, the UK was affected by a world pandemic of influenza – Hong Kong ‘flu, named because of the location of the earliest cases. Though it was estimated that some 30,000 people died in the UK (about a million globally), and the workload of general practice rose greatly, there was no widespread alarm. It returned in a lesser form in 1970 and 1972.

Hygiene remained important. Salmonella food poisoning, often following the consumption of cold or partially heated chicken, milk and eggs, could be traced back to poultry-processing plants, to their suppliers, to the breeding stock and to the food mixtures that were often heavily contaminated. Was there an effective system of inspection? asked the BMJ. Animal carcasses, environments, infected raw material fed to animals, processing plants and slaughterhouses were the source of human infections, and it was improbable that salmonellosis was the only example of an animal infection important to humans and animals, and to the economics of farming and food processing.56 A major achievement of the PHLS was the discovery that many cases of diarrhoea, for which no other bacteriological cause could be found, were due to Campylobacter jejuni, which was difficult to grow in the laboratory. It soon became apparent that such infections were even more common than those due to Salmonella.

Blood transfusion had long been known to be responsible, on occasion, for jaundice. This was especially so when large donor pools were used as the starting material for dried plasma. In the late 1960s, a test had become available for hepatitis B antigen, and blood donor screening was introduced. Worldwide elimination of smallpox was now in sight and the World Health Organization (WHO) intensified its campaign. In the UK, the risks from rare but serious complications of immunisation were much greater than from the disease itself.57 Routine smallpox immunisation in childhood ceased in 1971. In 1973, however, when smallpox was no longer considered to be a risk in the UK, an outbreak originated from a laboratory at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.58 There was a failure to follow up contacts, and secondary cases were initially missed. Spence Galbraith, a London area medical officer, had long argued the case for a centrally financed and co-ordinated national epidemiological service. There had been a lack of a centre for epidemiology in the NHS, unlike the case in the USA where the Communicable Disease Centre had existed in Atlanta since 1946. Following the report on the handling of the outbreak, the Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC) was established in 1977 under Galbraith, as part of the PHLS, to handle outbreaks that crossed organisational boundaries. The value of the CDSC was proved in 1978, when a technician in Birmingham also contracted smallpox from a laboratory.

Marburg fever was the first of several new viral haemorrhagic fevers to be reported. In 1969 another was recognised, Lassa fever, named after the place in Nigeria where it was first seen. It was related to a reservoir of infection in sub-Saharan Africa. In 1976 a further one erupted in Zaire and southern Sudan, with appallingly high mortality. Hundreds died, including 40 hospital workers. The causal agent, resembling Marburg virus but serologically distinct, was called Ebola virus. Such untreatable and apparently easily communicable infectious diseases caused great anxiety. The risk that people might travel by air during the incubation period led to plans for high-security infectious disease units. Travellers returning to Britain with a temperature were sometimes suspected of Lassa fever, though the diagnosis was rarely confirmed. A laboratory worker at Porton Down accidentally pricked his thumb while working with Ebola virus and six days later became ill and was transferred to an infectious disease unit at Coppetts Wood Hospital in north London where a plastic isolater, developed by Trexler, was available for use.59 A permanent high-security unit was planned for Coppetts Wood but was delayed interminably while there were public protests and arguments about the design. The hospital was next to an infants’ school and the area medical officer said that the proper place for swamp fevers was swamps – not Haringey.

Malaria had been eradicated from Britain long before the start of the NHS, with the exception each year of a few hundred imported cases, usually in tourists, business people, children visiting parents who were stationed overseas, immigrants returning home for a visit and, to a lesser extent, new immigrants. In the 1960s, the number of cases had been low, probably because of worldwide mosquito eradication programmes. The number of cases in Britain reflected the changes taking place in the tropics. There were great hopes that DDT and other insecticides would make possible the control of malaria by eradicating or reducing mosquito populations. It was a bitter disappointment to find that mosquitoes could develop resistance to insecticides, and that organophosphate residues from the insecticides were entering human food cycles.

In 1976, an outbreak of 180 cases of severe respiratory disease with 26 deaths occurred in the USA among people who had attended an American Legion convention. The bacterium responsible for ‘Legionnaires’ disease was rapidly isolated. The first British outbreak occurred in Nottingham in 1977. The infectious agent was subsequently found in water from cooling towers and air-conditioning systems, and the infection might therefore circulate throughout buildings.60 Further British outbreaks included one in London, near the BBC in Upper Regent Street. Some episodes of illness many years previously could now be attributed to the same cause, for samples of patients’ blood had been kept.

Sexually transmitted disease

Syphilis was under control, but gonorrhoea and non-specific urethritis were still increasing. A hundred years previously, the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) had argued that venereal disease (VD) was a just retribution for sin. Now it was seen as a penalty of ignorance in the young, for which their elders were responsible.61 Ambrose King, the venereologist at the London Hospital, warned about the possible failure of the VD services. The public was ill-informed, doctors were poorly educated in the subject, the facilities for treatment were often in the poorest buildings in the hospital, laboratory standards varied, and contact tracing was inadequate. King wrote that VD did not appeal to tender hearts and swayed no votes. Most money went into researching the complex problems of a few, little into really big medical problems affecting large numbers of people.62

Orthopaedics and trauma

Moorgate

On 28 February 1975, at 8.46am, a tube train failed to stop at Moorgate and ploughed on into a brick wall, compacting the first three coaches into a tangle of metal. Why the driver did not stop was never fully understood; there seemed nothing wrong with the train. At 9am, St Bartholomew’s Hospital was asked by the London Ambulance Service to send a doctor to the site. A casualty officer left in an ambulance with a medical student and a small first-aid bag and, on arrival, called for a resuscitation team. It was hard to know the magnitude of the disaster or to reach the casualties. Death was difficult to diagnose; heart sounds were inaudible because of the noise of pneumatic drills close by. Cutting equipment, lighting and ventilation were needed in the confined area of the rescue; but 74 live patients were evacuated in 13 hours. Because of the problem of getting to the wounded, it was 24 hours before it was clear that no one else was living.

Forty-three people died from head injuries and traumatic asphyxia, and two later in hospital from crush syndrome.63 Forty-one were admitted, and the slow but steady arrival of the injured meant that the small accident department at St Bartholomew’s Hospital was not overwhelmed. Barts was flooded with people wishing to give blood as a result of appeals on the radio, and while the hospital’s accident plan worked well, it was apparent that disaster planning should cover more than a single hospital. It was clear that there was no national system of approaching major accidents, or giving the recently developed specialty of accident and emergency (A&E) surgeons a centre place in disaster planning. Even a system of clearly marking dead victims was missing, to avoid time being wasted by the rescuers on repeatedly confirming death. Moorgate brought the need for wider disaster planning to be taken seriously.

Fractures

Organisations such as Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) continued to develop systems of fixation, improving the design of tapped screws to fix bone fragments, and developing the use of implants to span fragments and maintain length and alignment. Road traffic accidents remained a major feature of the work of orthopaedic departments. Because of the high incidence of head injury among motorcyclists, crash helmets were made compulsory in 1974; paradoxically the enforcement of their use meant that more motorcyclists survived their head injuries, and presented orthopaedic units with severe multiple injuries that formerly would have been seen only in the mortuary.

Hip replacement had emerged as one of the most important developments of modern surgery. A wide range of less-sophisticated operations (hip fusion, arthroplasty and new femoral heads) were now superseded by total replacement as the treatment of choice. In 1972, John Charnley reported long-term follow-up of 379 operations, carried out between 1962 and 1965, with excellent results.64 The need for surgery of the knee was at least as great as in the hip, but the mechanics of the joint were much more complex. Caution was needed because, if the operation went wrong, putting matters right was difficult. In the 1950s and early 1960s, hinge joints had been used, but they tended to loosen or break. Major effort went into development; Michael Freeman introduced a prosthesis in 1968 in which the joint surfaces alone were replaced, the upper with metal and the lower with polyethylene – the condylar knee replacement.65 It depended upon the patient’s own ligaments for stability and was not suitable in cases of gross destruction of the joint, but the design was progressively improved. In the 1970s, a two-piece prosthesis with a mechanical link was introduced. The failure rate remained higher than with the hip and, although the relief from pain was substantial, a walk across uneven ground was seldom possible.66 Initial experiments were undertaken with other joints, the shoulder and the elbow. All operations had the potential to produce problems – infection, loosening of the components or the wearing out of the prosthesis.

Cardiology and cardiac surgery

With better forms of treatment, the prevalence of heart failure, particularly from high blood pressure, fell. Heart attacks, most dangerous in the first minutes, presented an increasing problem. A big reduction in the mortality of the disease depended on prevention rather than technology. Evidence incriminated high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, a high intake of saturated fat from dairy products and physical inactivity. Many common foods seemed ‘super-saturated’– from roast beef to bangers and mash.67

In 1971, Brighton followed Belfast in the introduction of mobile coronary care ambulances, staffed by specially trained personnel who could recognise abnormalities of heart rhythm from the ECG, and correct them by the use of a defibrillator.68 Because there might be a delay before a call was received, there were doubts about the effectiveness of such services. In hospital the technology of coronary care units steadily improved, with automatic preset alarms warning nurses if the patient’s heart beat became too fast or slow, and indwelling cardiac catheters to monitor heart function. From six weeks’ bed rest in hospital, the norm in 1948, treatment had moved on. By the 1970s, experience showed that rapid mobilisation could be advocated confidently. In an uncomplicated case, the patient could be out of bed in a day or two and discharged in a week to ten days. It was now known that, within a month, the damage to the heart had largely healed and a normal life could be resumed.69 Archibald Cochrane was responsible for a study from Bristol, which revealed that selected patients treated at home did as well as those treated in hospital, and raised a question about the effectiveness of hospital care. However, the groups studied differed in their characteristics, and the study did not alter policy on hospital admission.

After a slow start, ultrasound (echocardiography) was increasingly important in cardiology, particularly in the assessment of valve disease. Heart valve damage because of rheumatic fever had been a major problem. By the 1970s, the scene had changed for two reasons. First, there had been an astonishing fall in the incidence of rheumatic fever, probably related to better housing that reduced overcrowding, and possibly a diminished virulence of the alpha-haemolytic streptococcus or better control of infections.70 Second, the surgical treatment of damaged heart valves had improved and was now a routine procedure. The death rate during operation for valve replacement was about 10 per cent and, although patients never regained the heart function of a healthy young adult, most were well satisfied with the improvement. The valves might be mechanical, for example, the Starr-Edwards caged-ball type that proved highly durable, or tissue, human ‘homografts’ or pig aortic valves, both of which were widely used but less durable.71

Infants and children with congenital heart disease and a poor chance of survival had been among the earliest cardiac surgical patients. Initially, because of the limited techniques available and the complexity of the abnormalities, full restoration of normal anatomy and function was seldom possible. Now major abnormalities were increasingly tackled in units such as Great Ormond Street, the Brompton and Guy’s hospitals, where there was great expertise in the care of small and sick infants.

The acceptance that surgery had a place in the treatment of coronary heart disease was largely the result of work at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio. In 1962, selective coronary angiography was introduced, which showed the position of blocked arteries, and by 1967 a surgical technique was developed to use a graft to bypass obstructed coronary arteries. The ability to stop the circulation and use a heart-lung machine (perfusion) gave the surgeon enough time to perform the operation. Surgery was found to improve angina better than medical treatment. By 1971/2, increasing numbers of operations were performed in Britain and the procedure began to dominate cardiac surgery.72 By 1974, the mortality was as low as 3 per cent in patients with severe stable angina.

Surgeons had been doing experimental heart transplants in animals for some years. A human heart transplant was carried out by Christiaan Barnard in South Africa in 1967. Norman Shumway then performed two at Stanford, California. Early in 1968, the Board of Medicine of the American National Academy of Sciences issued guidance on the experience, laboratory facilities and ethical safeguards that should be in place in cardiac surgical centres considering transplantation.73 The first heart transplant in Britain was carried out at the National Heart Hospital by Donald and Keith Ross on 3 May 1968. There was a second, but both resulted in the patients’ death. The UK surgeons had underestimated the need for careful patient selection and the problems of tissue typing, and they lacked the laboratory and pathology services that Shumway had. They misjudged the media interest, and some senior members of the medical profession were highly critical of the operations and thought them attention seeking. The third UK transplant took place at Guy’s in 1969 and the Daily Telegraph published the name and biographical details of the donor, a nurse killed in a road accident. An unrepentant newspaper rejected the hospital’s protests. The BMJ thought it breathtaking that the paper thought it knew better what was good for the patient than the doctors or relatives.74

Worldwide, many hospitals undertook a few heart transplants, but few of the patients survived. Almost all units rapidly stopped heart transplantation and a voluntary moratorium seemed to come into force. The transport of brain-dead donors in ambulances was leading to widespread distaste. Concerned about the ethics of the operation, the adverse publicity and the costs, Sir George Godber convened a group of experts, including those involved with the London patients, to ensure that the medical profession acted on a matter of public concern. Sir George said that clinical decisions about the treatment of individual patients were for the consultants concerned, but the diversion of resources from other hospital work was a matter that involved management. The expert group advised that heart transplantation was still largely experimental and there was no advantage in replicating work being done elsewhere. Regions were told not to make special resources available to support programmes and, as a result, heart transplants ceased for the time being in Britain.75 Shumway and his team in Stanford quietly continued their clinical work and their long-standing research programme. In 1971 they described their first longer-term results and success rates were improving. Of 26 patients, 13 left the hospital, of whom seven were alive a year later. A further report of 150 consecutive patients between 1968 and 1978 showed a one-year survival rate of 70 per cent – comparable with that of renal transplantation. The success was the result of teamwork with full immunological, pathological and microbiological services. In 1977, the UK Transplant Panel defined the conditions required in cardiac surgical units planning heart transplantation, and the ban was rescinded in 1979.76

Organ transplantation

Organ transplantation began as laboratory research on animals, was used experimentally in humans by a few clinics, and became accepted as a form of treatment of general application.77 Sometimes, as in liver transplantation, the mortality was extremely high at the beginning, but with experience it diminished substantially. The search for new and more specific immunosuppressive agents proved frustrating. Roy Calne, an English surgeon then in Boston, investigated the use of a derivative of 6-MP, azathioprine, used in the treatment of leukaemia, and showed that it prevented the rejection of kidney grafts in dogs. Subsequently, the introduction of cyclosporin in the late 1970s, combined with steroids, changed the whole picture.78 Getting excellent results in many patients, even with kidneys transplanted from unrelated donors, was now possible. Liver transplantation, first reported in 1963, was more difficult, particularly as the liver was sensitive to interruption of its blood supply, and had to be cooled rapidly and perfused if it was to survive until reimplantation.79 Nevertheless, the procedure was increasingly successful and a joint programme began at King’s College Hospital and Addenbrooke’s in 1968. By 1979 there had been 83 liver transplants, with steadily improving results.80 Research in basic immunology and tissue typing allowed clinicians to select donors with theoretical expectations of better results. The improvements in immunology also made bone marrow transplantation possible and, in the late 1960s, a role for it was identified in aplastic anaemia (failure of the bone marrow to produce blood cells) and leukaemia.81 Although these techniques were effective, they were costly. Clinicians did not always discuss the financial consequences with hospital management before beginning programmes locally.

Renal replacement therapy

It was now well established that active life could be prolonged in renal failure by maintenance dialysis and renal transplantation, but lack of facilities meant that most of those who would benefit still died.82 Home dialysis did little to relieve the pressure, although two-thirds of patients on dialysis treated themselves in their own homes. This was, in part, because of slow opening of new dialysis units and partly because of the risk of hepatitis B, although the control measures that were introduced in 1970 were largely effective.83

In the 1970s, outbreaks of encephalopathy and bone disease occurred in various dialysis units, and bone disease became a major problem. It often seemed that not a week went by without a dialysis patient sustaining a fracture. Alfrey and colleagues in the USA associated the encephalopathy in dialysis patients with aluminium toxicity. A geographical variation of toxicity that was associated with levels of aluminium in the water supply was found.

After five years’ effort, dialysis units were accepting only 500 patients a year out of an estimated potential three times that size. Once patients were on treatment, they were there for years, blocking the units for new cases. Expansion of transplant facilities was urgently required, for a successful transplant removed the need for regular dialysis, made a place available for another patient and was probably cheaper in the long run. Kidneys were scarce. A national organ-matching and distribution service was established in 1972, and it was found that many first transplants rapidly failed, probably reflecting the low quality of donor kidneys.84 Increasingly, kidneys from living donors, often relatives, were used. The results were better and the effect of removal of a kidney from an otherwise healthy person was negligible.85 Antony Wing, a nephrologist at St Thomas’ Hospital, produced a graph showing a relationship between the total number of renal patients on programmes in different countries and the gross national product of each. The prospect of survival apparently depended on the economic productivity of the country of residence.86 Dialysis and transplantation were now both established procedures and were interrelated. Neither could stand alone, for patients might need to move from one treatment to another, for example, if a transplant failed.87

Ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery

A new surgical approach to the internal auditory canal was introduced by Ugo Frisch in Zurich. Hopkins had developed his fibreoptic lens system in 1954, but it was not until the mid-1970s that fibreoptic endoscopy revolutionised the examination of the nose and sinuses, also making possible the development of endoscopic sinus surgery.

Ophthalmology

Developments in operating microscopes, instruments and lasers were applied to the diagnosis and treatment of eye disease, leading to operative procedures that were often time-consuming for the surgeon but made earlier discharge possible. Better anaesthesia and less-traumatic surgery led to successful surgery on older patients than ever before, and they were operated on at an earlier stage of disablement.88 Phacoemulsification, a method of breaking up the opaque lens followed by aspiration to remove the lens fragments, was introduced into cataract surgery by Kelman in 1967.89 Increasingly, lens implants were the treatment of choice.90 Once, a cataract operation had been followed by three weeks in bed. Now early mobilisation was the order of the day. Sometimes surgeons extracted both cataracts at once, not generally regarded as good practice. Patients could expect to be up and watching television two days after operation. Some diseases had previously been untreatable, for example, the retinal damage found in most diabetics after 10–20 years. The Birmingham Eye Hospital reported a controlled series showing that photo-coagulation by laser destroyed the growth of abnormal new blood vessels, and could arrest the development of the disease.91

Cancer

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw a breakthrough in cancer chemotherapy. Gordon Hamilton-Fairley, at St Bartholomew’s, saw what was happening in the USA and had the vision and drive to fight for chemotherapy and oncology in the UK. In the 1950s, acute lymphatic leukaemia had proved to be curable. In the 1960s, it was the turn of Hodgkin’s disease, which had usually been fatal, though treated for many years by radiotherapy and the early cytotoxic drugs such as nitrogen mustard. In early cases, radiotherapy had cured a few patients. Combination therapy was discovered almost by chance. In 1964, the National Cancer Institute put together four drugs, each of which had some therapeutic effect but different toxic effects. The combination they chose to use was hard to better, and consisted of nitrogen mustard, oncovin (vincristine), prednisolone and procarbazine (MOPP). There were apparent cures, which led to a redoubling of effort. The combination of vinblastine and chlorambucil raised the remission rate to 63 per cent.92 The radiological technique of lymphography, which made it possible to see affected lymph glands in the abdomen, and biopsy of spleen, bone marrow and liver, showed that the disease spread progressively. The spread could be accurately staged (assessed), and improved irradiation facilities made it possible to treat larger volumes of tissue. With increasing success, it became imperative that patients, often young adults, were handled from the outset at centres of expertise. Between 1972 and 1977 there was also a dramatic improvement in the remission rate of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.93 Cisplatin, introduced in 1972, had been discovered accidentally after Rosenberg, studying the effect of electrical currents on bacterial growth, found that bacteria did not separate properly. It was the platinum electrode that was responsible and the guess that something that stopped bacteria dividing might do nasty things to cancer cells led to further work. It proved useful for several tumours, including testicular cancer.

Openness with patients was now required, for the new patterns of chemotherapy were not compatible with reticence about the diagnosis.94 On both sides of the Atlantic, enthusiasm grew among oncologists. Perhaps all that was necessary was to discover the right combination of drugs and each cancer in turn would be cured. A campaign in the USA to ‘conquer cancer’ painted a rosy picture of the outlook, with little stress on the poor prognosis of the more common cancers such as breast, lung and stomach. The mortality for cancer of the breast had altered little in 50 years. Since the 1950s it had been known that some breast cancers were hormone dependent. Anti-oestrogens provided a possible line of attack but most had severe side effects, making them unacceptable to most doctors and patients. In the early 1970s, several compounds, such as tamoxifen, were reported as arresting or reversing tumour growth. They became widely used, first in advanced breast cancer, subsequently at earlier stages, and to stop recurrence in the other breast.95 Chemotherapy was already well established in advanced and inoperable disease and was used to reduce tumour size and make radiotherapy easier. With the discovery that tamoxifen and cytotoxic treatment improved the results, there was a swing away from radical surgery, partly because of a growing belief that treatment influenced survival less than the behaviour of the tumour and the extent of the disease at the time of presentation.96

The results of screening for cancer of the cervix began to be analysed and there was debate over its effectiveness. In 1976, the Canadian government published a report of its experience with mass screening. The incidence of the disease had fallen alongside the introduction of the programme, and, although it was not possible to prove that screening was responsible, the report concluded that many cases of carcinoma that were still localised to the cervix would have spread had they not been treated.97

A further report on smoking was published in 1971 by the RCP. Some 50,000 deaths a year could conservatively be attributed to it, and the list of associated diseases now extended to chronic bronchitis, coronary artery disease and cancers of the mouth, pharynx and larynx.98 Cigarette consumption continued to rise, although the prevalence of smoking was beginning to fall. Three factors were recognised as affecting consumption: health publicity, tax increases, and controls on smoking in the workplace.

Obstetrics and gynaecology

The number of maternal deaths had fallen from 67 per 100,000 in 1952 to 19 per 100,000 in 1969. The causes remained the same: abortion (other than termination of pregnancy), pulmonary embolism, haemorrhage and toxaemia.99 The improved results were not due to any one factor but to higher standards of surveillance, earlier detection of complications, and more effective preventive action and treatment.100 A healthier population played its part as well.

Hospital deliveries were rising; by 1968, the figure was 80 per cent. The average length of stay after delivery, however, continually decreased and an increasing number of maternity beds opened. As hospital confinement increased, GPs increasingly restricted their involvement to antenatal and postnatal care.101 Babies were generally delivered by midwives both at home and in hospital, but there was little contact between the two branches of the profession. In 1967 a committee was established, chaired by Sir John Peel, to consider the future of the domiciliary midwifery service and the need for maternity beds. The findings of the Perinatal Mortality Survey undertaken by the National Birthday Trust Fund influenced the Peel Report, published in 1970.102 Cranbrook had recommended a 70 per cent hospital confinement rate, Peel now advocated 100 per cent, and both assumed that hospital delivery was safer without actually establishing this. It became policy to concentrate obstetrics in properly equipped and staffed units, and to discourage isolated GP units. It was the death knell for the domiciliary midwife, who found that the work she had chosen and which she enjoyed was now branded as unsafe and inappropriate.103 District midwives were retitled community midwives and became part of the primary health care team, working with GPs. Home birth was barely viable. As the numbers fell, neither GPs nor domiciliary midwives had enough experience to give them the confidence and the skills required.