Chronology

2008

Background

Gordon Brown PM

Global financial crisis

Burma cyclone/Chinese Earthquake

Beijing Olympics

Russian/Georgian conflict

NHS events

Alan Johnson SOS

Regional (Darzi) reviews

Final Darzi Review Report, High Quality Care for All

2009

Background

Israeli invasion of Gaza strip

Barack Obama President of USA

Parliamentary/MP financial scandals

UK Population 61 million

Copenhagen climate conference

NHS events

NHS Constitution

Mid-Staffordshire Report on poor-quality health care

Care Quality Commission takes over from Healthcare Commission

Andy Burnham Secretary of State for Health

Financial stringency – Nicholson Challenge to save £20 billion

Swine flu concern and mass immunisation

Prime Minister’s Nursing Commission

2010

Background

Haiti earthquake

Obama’s historic US health care plan

Election – LibDem/Conservative coalition, David Cameron PM

Gulf of Mexico BP Oil spill

iPad launched

NHS events

Andrew Lansley SOS

Equity and Excellence, liberating the NHS

Healthy Lives, Healthy People – public health White Paper

Royal Centre for Defence Medicine (Birmingham) replaces military hospitals

2011

Background

‘Arab Spring’ uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Syria and Libya

Japanese earthquake/tsunami/nuclear power station problems

Widespread riots in English cities

Euro/Greek financial crisis

NHS events

Health and Social Care Bill

“20 Trusts with major cash problems”

2012

Background

London Olympics

NHS events

Passage of Health and Social Care Act

Jeremy Hunt Secretary of State for Health

2013

Background

Cyprus financial problems

NHS events

New structure introduced in April

111 emergency phone system introduced

2014

Background

Russia annexes the Crimea

Scots vote to remain in the UK

Multiple Middle East conflicts & emergence of ‘Islamic State’

UKIP make progress in polls

Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act

NHS events

Simon Stevens new Chief Executive of NHS England

NHS England 5-year view

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

2015

Background

Conservative election victory

‘Islamic State’ & European migration crisis

NHS events

Greater Manchester decision to merge health and social care budget

2016

Background

UK votes to leave the EU (Brexit)

USA elects Donald Trump as 45th President

NHS events

DevoManx inaugruated

Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs)

2017

Background

General election. Conservative majority eliminated

NHS events

Jeremy Hunt Secretary of State for Health

Move to explore Accountable Care Organisations

The seventh decade

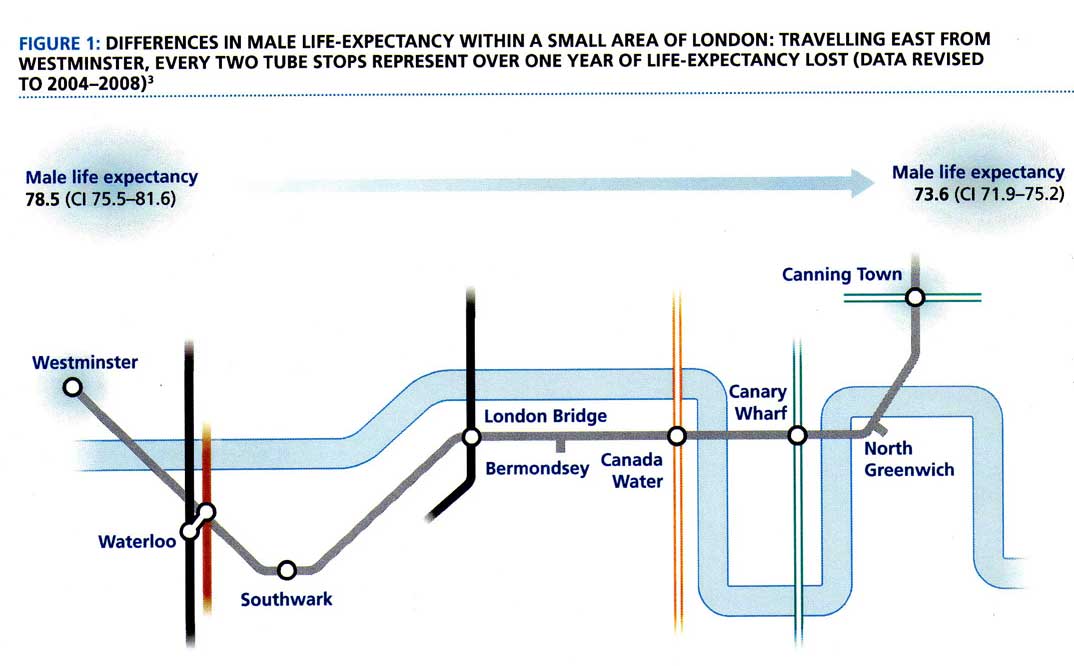

In the seventh decade of the NHS, the costs of healthcare continued to rise, fuelled by an ageing population, greater public expectations, the high cost of new treatments, air pollution and, in the view of many, worsening social determinants of health.

Yet, at a time of rapidly escalating demand, a disruptive, demoralising and distracting reorganisation was imposed during a period of economic crisis. A worldwide financial problem in 2008 had rapidly escalated. A crisis in the USA caused by ‘sub-prime’ mortgage loans, repackaged as ‘derivatives’ on which there was default, escalated into global economic recession. Tax revenues fell and social security payments rose. The housing market was depressed for a while, though in the south properties were increasingly unaffordable while appreciating partly because of an influx of foreign property investors. Labour’s control of the NHS ended in May 2010 when the party polled just a few seats fewer than the Conservatives who, in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, formed the new government. The Coalition imposed economic stringency to reduce the deficit and, five years later, the Conservatives won a surprise majority as the country emerged slowly from recession, Jeremy Hunt remaining Secretary of State. In his first major speech, David Cameron, again Prime Minister, pledged improvement of care outside the hospitals and, for the hospitals themselves, a full seven-day service. His decision to call a referendum on membership of the European Community led to a majority for ‘Brexit,’ triggering his resignation and a new Prime Minister, Theresa May. The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) increased its strength and had attained its main objective.

The life pattern of the technological younger generation differed from that of their parents. If in work, they were insecure; they married later and had fun in the meanwhile. Social media multipled. Family responsibilities were postponed. With the rise of cohabitation, the ‘single never married’ showed the greatest rise of any census category, 35 per cent of the over-16s. The population of the UK was increasing by some 400,000 a year, half because of an excess of births over deaths, half an excess of immigration (some 500,000 a year) over emigration. London was the most popular destination, with an increase of about 100,000 a year, for it provided employment for a myriad of European citizens facing unemployment in their own, often Southern, European countries.

Public sector workers took strike action against the cutbacks imposed by a governments dealing with the recession. Social attitudes were changing; there should be “no more something for nothing”. The United Nations’ eight millennium development goals, for example, combating hunger, child mortality and AIDS, were unlikely to be met as rising food prices and the cost of oil pushed millions more into poverty. In 2011, the Arab Spring culminated in uprisings against autocratic regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. The radical ‘Islamic State’ emerged as Syria and Iraq experienced a full-scale and frightful civil war, culminating in mass migration. Russia annexed the Crimea. Natural disasters, such as an earthquake in Haiti with 200,000 dead, and an Ebola crisis, stretched aid agencies.

A historic decision under Obama set in train a continuing process of extending health coverage by the Affordable Care Act to almost all of the legally resident USA population, and created incentives to contain the unaffordable growth of US health care costs. The attempts by his successor, President Trump, to overturn the plan largely failed.

If, in the sixth decade, the NHS seemed dominated by the turmoil of Labour’s multiple reorganisations, the seventh was worse. The five years of the coalition government fell into two halves. The first was devoted to the debate on, and passage of, the Health and Social Care Bill, designed to increase competition and devolve decision-making. The second was a damage-limitation exercise following Andrew Lanlsey’s disastrous reforms, with attempts to handle increasing financial problems, a process continuing under the Conservatives after election. Continuing stringency and the knock-on effect of cuts in local authority social services exacerbated problems.

Public satisfaction with the NHS was, however, stable.1 The National Centre for Social Research had conducted annual surveys since 1983.2 When Labour had entered office in 1997, only a third of people (34 per cent) were satisfied with the NHS. By 2009, satisfaction stood at 64 per cent and was 70 per cent in 2010, the highest level since the survey began. The reduction in waiting times for hospital inpatient and outpatient services was primarily responsible and the increased allocations to the NHS had probably helped. In 2016, public satisfaction with the NHS was 63 per cent, still high by historic standards. Satisfaction was broadly the same as in 2015, and could be split into three phases: ‘steady growth’ from 2002–2010, ‘a sudden drop’ in 2011, and ‘little change’ from 2012–2016.

Health services internationally were hit by a ‘perfect storm’. Money was tight but people’s expectations were increasing in a ‘me too’ society. Technology was providing a growing number of expensive treatments, radiotherapy was far more precise and effective, imaging of a quality unbelievable only a few years previously, and some 40 new drugs for cancer were in the offing, each costing some £2,000–3,000 a month. The population was ageing, bringing increased costs, and death was seen as ‘optional’ – to be postponed if enough money was spent. How could one pay for the triumph of medicine? Increasingly problems in the elderly, which required both health and social care, led to the idea of unifying the system and, in 2015, the Coalition (in a surprise decision) decided to implement this in Greater Manchester using regulations rather than an Act to make it possible.

The 60th anniversary in 2008 was widely commemorated. Health Service Journal listed the 60 people considered most influential, Bevan being the winner.3 Few publications celebrated clinical developments or the improving service to patients, and most dealt with macro issues of politics and funding. Parliament’s The House magazine produced a supplement on the Secretaries of State of the previous 30 years, and articles by each one.4 Frank Dobson attacked the health policies of his party and its accent on the marketplace. Alan Milburn believed that devolution had not proceeded far enough and suggested that the better local authorities might undertake health service purchasing. The King’s Fund produced an analysis of changing workload, finance and waiting times over 60 years. 5 The Nuffield Trust published Rejuvenate or Retire, in which senior figures mused on the past performance and future possibilities and agreed that the NHS should remain taxpayer-funded and free at the point of use.6 When radical alterations had been raised 20 years previously with Mrs Thatcher, Sir Kenneth Stowe, then Permanent Secretary, recalled her saying, “There is no constituency for change”. Most agreed with the purchaser–provider split, that the private sector offered important competitor services within the NHS, and that more decisions should be taken locally. None predicted the financial crash only months later, which had a massive effect on the NHS and all public services.

The four UK Health Ministers restated the principles of the NHS: a comprehensive service available to all; access to services based on clinical needs and not on the ability to pay; aspiration to high standards of excellence and professionalism; NHS services reflecting the needs and preferences of patients, their families and their carers; working across organisational boundaries with other organisations in the interests of patients, communities and the wider population; commitment to the best value for taxpayers’ money; making the most effective and fair use of finite resources; and accountability to the public, communities and patients that the NHS serves.

Labour had followed the Conservative’s Patients’ Charter with a ‘Constitution for the NHS’, pulling together existing rights, responsibilities and pledges, the right to make choices about their care and “to expect local decisions on funding of other drugs and treatments to be made rationally following proper consideration of the evidence”.7 When published in January 2009, the response was lethargic.

Reviewing Labour’s reforms

Throughout the previous decade, Labour had introduced one reform after another. Now it was stocktaking time. There had been four important innovations: Foundation Trusts; greater NHS use of the independent sector; patient choice; and payment by results. RG Bevan wrote that “healthcare systems had three main goals, to control total costs, to achieve equity in access by need and to achieve excellence in performance (short waiting times, satisfied patients, and good outcomes)”.8 The problem was improving the performance of providers. Before 1991, the NHS had a hierarchical integrated model in which the same organisations were responsible for determining the needs of their populations and for running providers. Such organisations could be funded equitably for their populations or for the performance of providers, but not both. The internal market with a purchaser–provider split, in which purchasers were funded for their populations and contracted with independent providers, was an attempt at an answer. England had tried four variations of this model to improve provider performance: competition between 1991 and 1997; partnership between 1997 and 2000; publishing performance in ‘star ratings’ between 2001 and 2005; and again competition from 2006, changing the methods of payment. In June 2008 the Audit Commission published Is the Treatment Working?.9 The development of Foundation Trusts and patient choice was behind schedule, and the scale of independent sector treatment centres was limited.

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland had different systems as a result of the devolution of health service management to the four nations of the UK. Marked differences were emerging in hospital services. Policies led to different incentives. In England, targets to improve performance, payment by results and the increasing emphasis on the provider/commissioner split and patient focus had driven change. Scotland had abolished the internal market and had integrated boards, purchasing and providing primary and secondary care; Wales did not separate purchasers and providers either, was looking at the Scottish model but was experiencing major waiting list problems; and Northern Ireland continued with its integration of health and social services. Several studies showed that, compared with the others, England had shorter waits in Accident and Emergency (A&E), even though the reduction of waiting times seemed associated with a greater rise in attendances than elsewhere. Proportionately, more patients were discharged rapidly, within a day of admission, in England.

In 2010, Nuffield reviewed their experiences, suggesting that England was comparatively more efficient, spent less on health care, had fewer doctors, nurses and managers per head of population, and was making better use of the resources it had in terms of higher levels of activity, crude productivity of its staff, and lower waiting times. Three years later, a follow-up report revised this view, suggesting that the different policies adopted by each country appeared to have made little difference to long-term national trends.10 The King’s Fund, in Understanding New Labour’s Market Reforms (2011), felt that Labour had gone much further in introducing changes and encouraging market competition than the Conservatives in the 1990s, the fears then voiced had largely not come to pass, but their impact was also more limited than their proponents had hoped.11 The NHS “was still some distance away from functioning as a fully-fledged provider market for publicly financed care. The system continued to be run by a closely managed hierarchy, while operating in a more market-like way in specific respects.” Hawkes wrote that the reforms had emerged piecemeal for, while there were policy statements, a clearly articulated plan was never put before Parliament or the electorate, in part because it avoided a showdown in the Labour Party ranks, not least between Blair and Brown who differed substantially on issues such as patients’ choice. “The reforms worked but the politics of the reforms was a disaster.”12

Before losing power, Labour still had shots in its locker. In May 2008, Lord Darzi published Leading Local Change:The Next Stage Review.13 His final report, High Quality Care for All, appeared at the time of the 60th anniversary.14 It was followed by separate strategies on primary and community care, workforce issues and informatics. The key effects of the clinical slant of the Darzi proposals were to press the quality agenda and to raise the profile of service configuration in hospital and community services. The King’s Fund summarised this final report.15

|

London Reports |

National Darzi reports |

|

The case for change (2006) |

|

|

Saws and Scalpels to Lasers and Robots – clinical change (2007) |

Our NHS, Our Future (interim report, October 2007) |

|

A Framework for Action (July 2007) |

|

|

A local hospital model for London (November 2008) |

High quality care for all – Final report (June 2008) |

|

The Shape of Things to Come – Stroke & Trauma consultation (February 2009) |

Andy Burnham (2009–2010), the last of Labour’s five secretaries of state, was a cast-back to Frank Dobson and the old Left. Different parts of the Department of Health now did not seem to speak to each other, and policies seemed increasingly chaotic. The use of competition to drive innovation, quality and choice as espoused by Paul Corrigan,16 a special adviser to Alan Milburn and Tony Blair and later a director in the London Strategic Health Authority (SHA), had become unappealing to No 10. Speaking to the King’s Fund in September 2009, Andy Burnham said that the NHS, not the independent sector, was the “preferred provider”.17 Unite, Britain’s biggest union and a major funder of the Labour Party, had petitioned the government to “roll back the privatisation of the NHS” and claimed a major victory. Burnham argued that reform meant working to improve existing services where they were “good enough”. When the 2010 election came, Labour reaped little advantage from its undoubted achievements.

Health policies under the Liberal/Conservative government

The 2010 election produced a Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition. Andrew Lansley became Secretary of State and, during the previous six years as Shadow Health Secretary, he had given much thought as to how to achieve his vision of a service in which private, not-for-profit and public providers competed against each other, and GPs commissioned services on behalf of their patients. Lansley arrived with a draft White Paper in his pocket: he had written a Conservative paper NHS Autonomy and Accountability Proposals for Legislation in 2007.18

Coalition government being unusual, joint policies had to be agreed. Danny Alexander and Oliver Letwin worked on a programme for government and had to square the Conservatives’ belief in markets as the way to reform the NHS, and the Liberal Democrats’ manifesto commitment to elected health boards and belief in democracy.19 As far as the NHS was concerned, the outcome, (on which Andrew Lansley had not been consulted), was a muddle. Nick Timmins explored the political manoeuvres as the original attempt to build on Labour policies became revolutionary changes.20 Lansley didn’t like it. His reaction was, “let’s find a way round it. Let’s show how it is unworkable and we can deal with it”. He wished to make his changes hard to reverse. Some of Lansley’s 2007 document was cut and pasted into the White Paper, with proposals such as the abolition of SHAs that had been in the Liberal Democrats’ manifesto.

Many were shocked by the scale of changes, which involved a huge Bill, complicated legislation, major administrative upheaval and a pitched battle with professional interests. It was not clear what the ‘reforms’ were designed to achieve, since public satisfaction was at an all-time high. Many seemed unrelated to the problems facing the NHS: demographics, technology, increasing demand and the financial crisis.21 They were complex, involving complicated and obscure legal provisions. Launched at a time of unparalleled financial problems, they were a distraction from the main task and never secured support from the people on whose agreement they depended. So began a two-year process, perhaps the messiest reorganisation the NHS had ever undergone, although the events prior to the 1974 reorganisation came a close second. Following the longest period of sustained spending increases in NHS history, stringency now struck so the NHS had enough to handle without major structural changes. Though the health service budget was ring-fenced, finances would be tight and management costs had to be reduced. Lansley was no believer in strategic planning and wished to reassess the Darzi-inspired London NHS restructuring. The chair of NHS London, whose vision of the future of London’s NHS had been painstakingly worked out and differed from Lansley, resigned in protest as much useful work was halted.

Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS

In July 2010, Andrew Lansley published his White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS.22 The major themes built on the internal/social market model. It had taken 50 days to bring forward proposals, compared with ten years for the Conservative administration in 1990 and six years for Labour in 2002. David Nicholson, the Chief Executive of the NHS, said “nothing in the system is left untouched”. 23 There had been no warning in speeches, manifestos or even the Coalition agreement of the scale of the change. They were immediately criticised by some as creating unnecessary turbulence, but early opinion was unconventionally split, with some ex-Labour advisers supporting the proposals and right-wing think tanks opposing them.

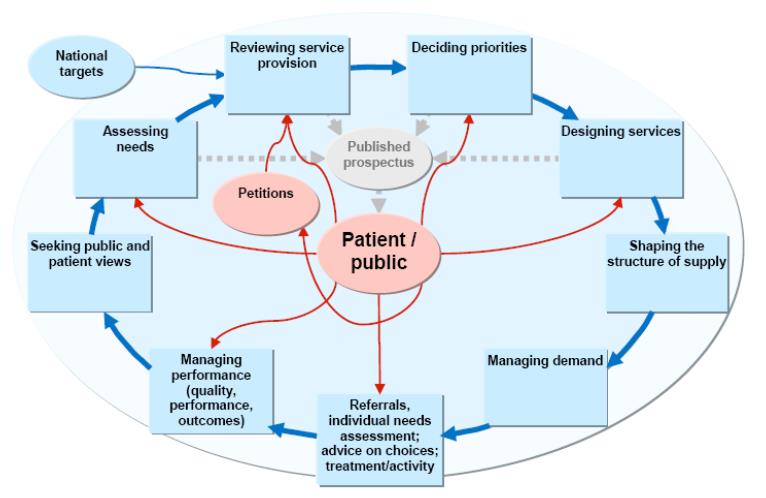

The Bill’s stated aims were to strengthen commissioning of NHS services, increase democratic accountability and public voice, liberate provision of NHS services (that is, make it easier for private organisations to provide services), strengthen public health services and reform health and care ‘arm’s-length bodies’. The ‘vision’ was a service delivering good outcomes and devolving decision-making to the front line. The encouragement of “any willing or qualified provider” led to concern that competition and “privatisation” of the health service were in Lansley’s mind and the regulations that ultimately came into force, increasingly opened up the NHS to competition from private providers. The abolition of the SHAs and the Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) removed all the bodies that had a responsibility to plan in a strategic way in accordance with a population’s need. National and regional specialist services would be commissioned by a new NHS Commissioning Board – NHS England – taking over many SHA functions.

On the commissioner side, 500–600 consortia of GPs would take responsibility for most of the NHS budget, transferred from PCTs. No other country had placed such emphasis on GP purchasing. A £20 billion efficiency saving by 2014, a reduction of 45 per cent in management costs, and a reduction in the number of management bodies was promised. Lansley’s 2007 paper had said: “We support the return of powerful, clinician-led commissioning in primary care – like that engendered by GP fundholding in the 1990s.”

On the provider side, NHS Foundation Trusts would have greater autonomy and independent sector providers were encouraged to compete for patients. There would be no cap on the income NHS Trusts could generate from private practice. The operation of the market would be overseen by an economic regulator, a new role for Monitor. Monitor would promote competition, regulate the prices paid to providers and ensure continuity of service provision. Public health functions would move to local authorities who would employ a director of public health and have a ring-fenced public health budget. Local authorities would also be given control over local health improvement budgets, and the power to agree local strategies to bring together the NHS, public health, and social care. Council-based public health teams would provide commissioning consortia with information, evidence, needs assessment, and the quality improvement support needed to commission integrated health services. Local authorities would establish Health and Wellbeing Boards to lead on improving the strategic co-ordination of commissioning. Patients would get more choice and control, so that services were more responsive and designed around patient needs. They would be able to choose their GP practice regardless of where they lived, and choose between consultant-led teams. More comprehensive and transparent information would help them. Management costs would be reduced so that as much resource as possible supported front-line services. The NHS would aim for outcome measures of quality rather than process measures or targets; GPs and hospitals would have to publish detailed outcomes of their care, including medical errors. Those commissioning care had to consider bids from well qualified private providers, and an increasing number of contracts subsequently went to the private sector – sometimes for clinical services, including community health services, out-of-hours GP services and (in the case of Hinchingbrooke), an entire hospital. Many changes did not need legislation. PCTs could and were merged. Separate commissioning and provider functions were established within the Department and within the SHAs to guide implementation.

The King’s Fund believed the extent of change was substantial and the pace rapid. Its Chief Executive, Chris Ham, wrote that the changes took forward reforms set out by Labour in 2002 and developed by Ara Darzi in 2008, and were both ambitious and risky.24 Following consultation, the Bill was published in January 2011. It was long and complex. Labour and health trade unions including the British Medical Association (BMA) and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) were strident in their criticism as was the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). In April 2011, the all-party Commons Health Select Committee, in a thoughtful review, demanded significant changes to accountability and that commissioning bodies should “reflect the range of other (clinical and non-clinical) considerations, including nurses and hospital doctors”.25 Commissioners must be able to facilitate necessary service reconfigurations. The reforms lacked a “strong narrative about why the inevitable upheaval they involve will be worthwhile”. The arguments often seemed either highly complex and technocratic or vague. In retrospect, senior Tories regarded them as the greatest mistake they had made in government.26 Reducing bureaucracy was a popular idea, but not strong enough, and the argument that the NHS had poor outcomes had often unravelled. The government had not made the case that this particular set of reforms was the answer.

Opposition mounts

An increasing wave of opposition, the report of the Select Committee and the views of some Liberal Democrats, led Andrew Lansley and David Cameron to “pause, listen and engage”. An NHS Future Forum was appointed under Stephen Field to examine the key issues. The process was becoming messy and many felt that Andrew Lansley, by attempting major reorganisation at the time of financial crisis, was living in a parallel universe described unkindly as “la la land”. The Forum reported in June 2011 with “deep seated concern”, believing that the Secretary of State should remain ultimately responsible for the NHS, commissioning consortia should include hospital doctors and nurses, their board meetings should be public, and stress should be placed on an integrated service.27 It doubted whether the correct place for public health in England was within the Department of Health. In their response, Ministers accepted most of the suggestions.28 The Right suggested that easing back on competition made it harder to achieve efficiency and the Left that the earlier proposals had been ill-conceived. Alan Milburn, the reforming erstwhile Labour Secretary of State, saw the modifications as unfortunate. The Times thought that the creation of clinical senates, health and wellbeing boards and other new machinery represented a victory for bureaucratic process and would slow change, rather than open the way to more efficient care.29 Many amendments were made to the Health and Social Care Bill in the Lords and it was referred back to Parliament for reconsideration. The British Medical Journal (BMJ) outlined the main remaining controversial issues such as privatisation, the role of Monitor and the responsibilities of the Secretary of State.30 The Future Forum remained in existence for another year, considering education and training, public health, information and integration.

An increasing wave of opposition, the report of the Select Committee and the views of some Liberal Democrats, led Andrew Lansley and David Cameron to “pause, listen and engage”. An NHS Future Forum was appointed under Stephen Field to examine the key issues. The process was becoming messy and many felt that Andrew Lansley, by attempting major reorganisation at the time of financial crisis, was living in a parallel universe described unkindly as “la la land”. The Forum reported in June 2011 with “deep seated concern”, believing that the Secretary of State should remain ultimately responsible for the NHS, commissioning consortia should include hospital doctors and nurses, their board meetings should be public, and stress should be placed on an integrated service.27 It doubted whether the correct place for public health in England was within the Department of Health. In their response, Ministers accepted most of the suggestions.28 The Right suggested that easing back on competition made it harder to achieve efficiency and the Left that the earlier proposals had been ill-conceived. Alan Milburn, the reforming erstwhile Labour Secretary of State, saw the modifications as unfortunate. The Times thought that the creation of clinical senates, health and wellbeing boards and other new machinery represented a victory for bureaucratic process and would slow change, rather than open the way to more efficient care.29 Many amendments were made to the Health and Social Care Bill in the Lords and it was referred back to Parliament for reconsideration. The British Medical Journal (BMJ) outlined the main remaining controversial issues such as privatisation, the role of Monitor and the responsibilities of the Secretary of State.30 The Future Forum remained in existence for another year, considering education and training, public health, information and integration.

By January 2012, medical and nursing professional organisations had become implacably opposed to the Bill, mainly because of the increased role that competition would play, but also because of the turmoil engendered when management effort was needed to handle major financial problems and the possibility that some changes could reduce the comprehensive nature of the NHS. Changes in NHS pension schemes were also significant. “The upheaval had been unnecessary, poorly conceived, badly communicated, and a dangerous distraction at a time when the NHS was required to make unprecedented savings” said the BMJ.31 Opposition increased, even within the Cabinet, the Prime Minister threw his authority behind the Bill, organisations such as the BMA, RCN and RCGP found themselves excluded from meetings, the Liberal Democrats sought more and more modifications, but eventually after over 2,000 amendments, the Act was passed in March 2012. Andrew Lansley was known to have commented that he could have achieved most of what he had wanted without legislation.

The Health and Social Care Act

Main legislative changes

- PCTs and SHAs abolished as part of a radical structural reorganisation, with new health and wellbeing boards being established to improve integration between NHS and local authority services.

- Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) to take over commissioning from PCTs and work with the new NHS Commissioning Board, NHS England, in doing so.

- Monitor to regulate providers of NHS services in the interests of patients and prevent anticompetitive behaviour.

- The voice of patients to be strengthened through the setting up of a new national body, Healthwatch, and local Healthwatch organisations.

- A new body, Public Health England, to lead on public health at the national level, and local authorities to do so at a local level.

- The secretary of state retains ministerial accountability to Parliament for the provision of the health service.

- New duties emphasised the need to promote research within the NHS and strengthen requirements to promote education and training.

Source: Health and Social Care Act32

The continuing development of health policies

Unstable, complex and obscure in its hierarchical relationships, the NHS did its best to make an inherently unworkable system work. The appointment of Jeremy Hunt as Secretary of State for Health in September 2012 marked the beginning of a slow process of restoring practicality to the service without an apparent U-turn. The creation of NHS England in 2013 was intended to distance the NHS from the political landscape. In practice problems landed on the desk of the Secretary of State as they had always done, and the Department intervened.33 New policy concepts emerged from many quarters. Announced in 2013, the Better Care Fund earmarked £3.8 billion to create a single pooled budget between health and local authorities. It was to improve the care of vulnerable individuals aiming to keep them out of hospital. It was expected to save a £1 billion and provide an opportunity for improvement, but assessment by the Public Accounts Committee in 2015 suggested mismanagement and found the savings achieved to be derisory. Early on the scene was Labour whose Shadow Health Secretary, Andy Burnham, announced a Whole Person Care approach, in line with the Michael Marmot health inequalities agenda. The vast majority of NHS funding would be handed to local authorities as an integrated budget for most health and social care − perhaps £90 billion. Health care would return to local authorities and their new Health and Wellbeing Boards. National services and primary care would still be commissioned centrally, but most spending would be under council control. In September 2014, the King’s Fund published its final report on the Future of health and Social Care in England. Chaired by Kate Barker, who came from a background of economics and finance, it drew attention to the apparent injustice of care costs for some conditions being free, and others (such as dementia) being costly to the patient. It suggested a ring-fenced budget unified for health and social care, free social care for those with critical or substantial needs, a variety of tax increases and a flat rate of prescription charges with no exemptions to meet the expense. A new dogma was unification of health and local authority care services, which seemed at odds with the purchaser–provider split.

Repeatedly it was said that the NHS had to change. But change into what? Some argued for the closure of many hospitals and a major transfer of care into the community. In July 2013, David Nicholson then Chief Executive of NHS England announced a major review of strategy over the long term – was the purchaser–provider split really appropriate when organisations such as Kaiser-Permanente did well without it? Did every Trust have to be a Foundation Trust? His review was overtaken by events. Financial stringency was still needed and the ‘Nicholson Challenge’ was rolled forward in The NHS Belongs to the People, which set out the problems, quality, patient experience, dementia and the increasing number of the elderly.34 A funding gap of £30 billion by 2020 was identified. David Nicholson had long had an ambivalent relationship with Andrew Lansley, and resigned as Chief Executive of NHS England. In his exit interview in 2014, he gave a damning account of how current NHS rules and structures were obstructing vital changes. “It’s not clear now who makes the decisions… If you’re going to make a big and ambitious change, who actually does it? That’s a real problem.35 To replace David Nicholson, an international search led to the appointment of Simon Stevens. Stevens was a fascinating appointment for he had been central to Labour’s earlier reforms. He had been plucked from obscurity years before by ‘Old-Labour’s’ Frank Dobson, but it was with Alan Milburn that he flourished. He had been a policy adviser to both Tony Blair and Alan Milburn, and he subsequently had extensive international experience. He had largely written The NHS Plan, introducing Primary Care Groups (PCGs) and later PCTs, then moved to become Tony Blair’s health special adviser.36

Stevens’ views differed from those of his predecessor. Speaking to the Commons Health Committee in April 2014, he said that he was a pragmatist, and saw advantages in competition. He thought that the merger and closure of small hospitals in the already centralised NHS might not always be wise, and that CCGs might take more responsibility for commissioning primary health care. Did all acute hospitals need a full complement of trainee doctors? Many European hospitals had consultant provided health care. Was there a case for multi-specialty groups uniting specialist, primary, community and social care with a population-based budget? As economic growth returned, he expected NHS funding to increase in real terms. In October 2014, NHS England published a Five Year Forward View.37 Even with savings on a massive scale, above-inflation rises in funding would be required. Wanless had pointed 12 years previously to the need for full engagement of people in maintaining their own health. They had not done so. The cost of obesity, smoking and alcohol misuse had to be cut. The NHS and the private sector should assist in health promotion.

The traditional divide between primary care, community services, and hospitals – largely unaltered since the birth of the NHS – is increasingly a barrier to the personalised and coordinated health services patients need. And just as GPs and hospitals tend to be rigidly demarcated, so too are social care and mental health services even though people increasingly need all three. Over the next five years and beyond the NHS will increasingly need to dissolve these traditional boundaries.

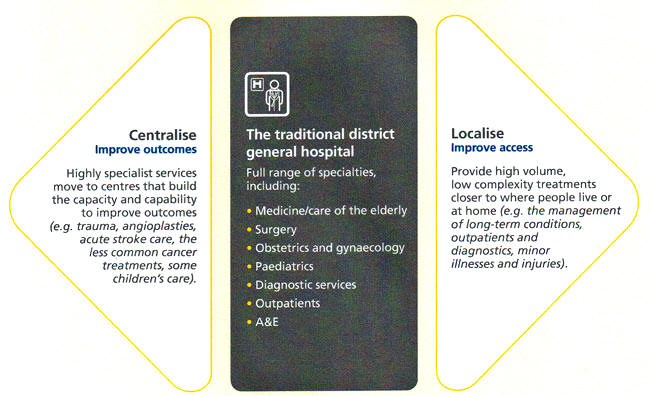

Barriers between primary and secondary care could be reduced by specialists working in proximity with GPs in the latter’s facilities (a multi-specialty community provider), or by hospitals taking over GP clinics and A&E departments uniting with out-of-hours services (as a primary and acute care provider). A standard pattern across England, such as the district general hospital (DGH) concept, was outdated, and a ‘one size fits all’ policy was no longer ideal. More investment in primary care was needed.

In 2014 the Secretary of State asked Sir Stuart Rose, from Marks and Spencer, to advise on how to attract and develop talent from inside and outside the health sector into leading positions in the NHS. His report – Better Leadership for Tomorrow – was critical; there was insufficient management and leadership capability to deal effectively with the scale of challenges faced. He also asked Sir David Dalton to look at how to end the isolation of failing hospitals from good management and practice, and how to enable the best-performing NHS organisations and most successful chief executives to establish national groups of hospitals or services as beacons of excellence. His report in 2014 saw the need for fast action to maintain providers, and felt that ambitious organisations with a proven track record should help others. Organisations should be part of a local ‘health economy’ and not remain in isolated independence.38 Jeremy Hunt was attempting to mitigate some of the worst of the problems of the Lansley changes. An additional £2 billion was announced for the service. PCGs were looking more like the erstwhile PCTs. Hunt, in an interview with Health Service Journal (HSJ) on 29 November 2014, said that “the market will never be able to deliver in the top priority area of integrated (care) out of hospital”... “choice was not the main driver of performance improvement, contrary to the emphasis placed on it by various governments and senior NHS leaders since the early 2000s... there are natural monopolies in healthcare, where patient choice is never going to drive change”. Emergency services and integrated care were among these.

His Five Year Forward View (2014) and follow-up documents encouraged the development of different models of the provision of care, the consideration of local “health care economies” that spread wider than individual providers and a “success” regime for those in great difficulty. There would be no single nationwide pattern. A dramatic example was the dissolution of boundaries in 2015 in Greater Manchester. From 2016, as part of a move towards devolved government in England, by the deft use of existing regulations and a delegated authority, Greater Manchester would be given control of their entire £6 billion health budget. The tariff and Monitor would be redundant, and CCGs would become budget administrators. Such a unified system had been a gleam in Labour’s eye. The Coalition, and later the Conservatives, rather than Labour would bring it to fruition at least in Greater Manchester.

Gradually, however, the Lansley dream of local autonomy and competition faded. Increased centralisation of guidance and finance, and the financial imperative of keeping within budgets in a harsh climate, brought it to an end.

Organisational structure in 2013

On 1 April 2013, the massive reorganisation of the NHS took place as a result of the Health and Social Care Act. Progressive revisions had increased the complexity and the number of bureaucratic bodies. New ones and old ones overlapped. SHAs and PCTs had been clustered and then abolished. Sir David Nicholson had moved in advance from the Department to become Chief Executive of NHS England, the Commissioning Board. It provided for the first time a statutory division between Ministers and the Department of Health and the commissioning and provision side of the NHS. The new NHS structure was incredibly complex.

The organisations

NHS England

See Parliamentary briefing March 2016 – The Structure of the NHS in England – a factual document with diagrams and some history.

Also NHS England Guide 2014 – Understanding the New NHS – with good organisational diagrams.

Andrew Lansley had designed the NHS Commissioning Board, NHS England, to distance politicians from the day-to-day management of the service and had legislated to remove them from detailed operational matters by restricting their powers under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. Nigel Edwards said that Lansley “appeared to believe that planning – or strategic commissioning – was not just unnecessary but positively bad and viewed SHAs’ planning as being close to a Bond villain in a dormant volcano stroking a cat – it was the sort of top down intrusion against which he had set his face”.

The Act established NHS England as independent and accountable, limiting the power of the Secretary of State, though the concept that government would draw back was soon shown to be nonsense. When any significant problem arose, such as failure to meet A&E targets, Ministers were quick to take charge, leaving NHS England high and dry. Government published a mandate setting out what the Secretary of State expected NHS England to deliver, initially by 2015.39 Five priorities included: improving standards of care; care of the elderly; dementia; multiple long-term diseases; and preventing deaths from the main killers. There were also a raft of subsidiary priorities. Could this be delivered at a time of retrenchment?

The chair, Professor Malcolm Grant, published its manifesto in The Times in April 2013 as NHS England assumed responsibility for the NHS £80 billion commissioning budget.40 NHS England set NHS funding of subordinate commissioning groups, and what the service was expected to deliver in the short and medium term. It had designed the new clinical commissioning system and tried to reinvent the strategic planning function by getting CCGs to work together, by using its muscle as a major purchaser of specialist care or more radically by pushing Academic Health Science Networks as market-shapers. It had four regional branches for London, the North (North West, North East and Yorkshire and the Humber), the South (South Central, South West and South East Coast) and the Midlands (East and West Midlands and East of England.) It operated under a mandate from the Secretary of State, setting out the objectives and policies for the NHS. A more peripheral tier of local area teams later changed to 12 subregions, with functions around the development of CCGs, emergency planning, quality and safety, and service configuration. There were three in London, a north east, a north west and a south London area team, working in a more integrated way. Nationally, ten area teams would undertake specialised commissioning. Once in power, NHS England began to establish policies that seemed to centralise rather than decentralise decision-making. According to the King’s Fund, the system now included many “largely autonomous bodies over which our new chief executive will not have control.”41 It issued much ‘guidance’. Intended to be a lean body, within a couple of years it had 15,000 employees. Monitor, before its merger with NHS Improvement, accused it of “imperial over reach”, as it flexed its muscles over issues such as the control of capital spending by Foundation Trusts.

In a further modification of central management in 2018, NHS England and NHS Improvement planned to work more closely together, with seven regional branches of each, jointly managed by a single regional director.

Public Health England (from 2013)

To “protect and improve public health and reduce inequalities,” Public Health England was established as a central organisation with four regional branches to lead public health initiatives. While not directly commissioning services, it related to the 152 top-tier local authorities which took over the public health budget (£5.45 billion over two years). It established surveillance systems and advised NHS England on campaigns that should be centralised, for example, on smoking and dementia. It supported local government, the local public health system and Directors of Public Health, providing leadership in responding to emergencies where scale was necessary. There had been arguments about whether it could mount an effective public health challenge to policies, being directly responsible to government. It became apparent that it was neither a campaigning body, nor equipped to evaluate policies for which evidence was weak or non-existent, such as annual health checks.

PCTs (ceasing in 2013)

The 2006 mergers had reduced the number of PCTs in England to 151, mostly coterminous with local authorities. They had been responsible for managing around 80 per cent of the NHS budget. PCTs divested themselves of community nursing services and, in roughly equal numbers, these were merged or amalgamated with acute hospital trusts, mental health trusts or aspirant community Foundation Trusts, although a few services went to private sector bidders, two in Surrey to Virgin Care. PCTs and the comparatively few Care Trusts were wound down and often clustered into groups with a single management team before their abolition in 2013.

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) (from 2013)

‘General practitioner-led commissioning’ had been a policy since 1991. GPs had a good idea of patients’ needs, their influence might shift care from hospital to the community, reduce the emergency admission rates, and involving clinicians in management was, in any case, a good thing.42 While PCTs had ultimately been responsible for all residents in a geographical area, CCGs would be responsible only for patients registered at practices within that group.

There were already models, (for example, in Northamptonshire) and, by 2012, 257 ‘pathfinder’ groups with populations of 150,000–250,000 covered 97 per cent of the country. General practitioners agreed the membership and representational structure and there was good involvement of most practices. In many cases, the boundaries that emerged were those of the previous PCT.

NHS England determined when the CCGs could take on commissioning and, by March 2013, 211 CCGs covered the country. From 1 April 2013, they became statutory NHS budget holders in their own right. CCGs tended to appoint managers, rather than doctors, as ‘accountable officers’. Initially they were quite small organisations employing 20–30 people, sometimes using commissioning support units to help, but they grew and often merged. Support units could be, but seldom were, private sector organisations – the profit margin available was too small. In most localities, many GPs had a financial interest in a local provider, for example, the organisation delivering out-of-hours care. The risk of a conflict of interest therefore arose. In general, they established themselves remarkably well and developed good relationships with their local providers, and though GPs viewed them more favourably than the erstwhile PCTs, the influence of general practitioners on commissioning was less than most had imagined. The way in which commissioning was organised – dispersing budgets formerly held by PCTs between CCGs, NHS England and local authorities – meant that there was no longer single population-based budgets for health care. A split between primary care and other services at a local level, and between specialised commissioning and general services, created divisions and significant problems. Simon Stevens was supportive of there being increasing commissioning by CCGs and flexibility including co-commissioning by CCGs that were rather too small for some forms of care. NHS England began to devolve the commissioning of the core general practitioner contracts to CCGs in 2017.

Foundation Trusts

First established in 2005, by 2010 there were 130 Foundation Trusts (FTs) and by 2014, 147. The number increased steadily but many Trusts were not well enough governed or in good enough financial shape to achieve Foundation status. William Moyes, the Executive Chairman of Monitor, felt that the performance of FTs had been impressive. A small élite was now exploring the full limits of their potential, with a handful aspiring to be truly world class. They had probably performed significantly better than other Trusts because they were already better managed.

The Health and Social Care Act had only modest effects on FTs. It changed the title of the board of governors to the council of governors. Their management boards would meet in public. Governors were given a duty to hold non-executives to account for the board’s performance and to represent the interests of FT members and the public. Governors could require one or more directors to attend a meeting to provide information on the directors’ performance of their duties, and annual reports must include information on any occasions where this power had been exercised. FTs would also have a duty to ensure that governors had the skills and knowledge to carry out their role.

Much more significant was the increased central direction of all Trusts and the amalgamation of Monitor into NHS Improvement. The accent on competition lessened, and central planning across all providers became more dominant. The difference between FTs and other Trusts was narrowing.

Non-Foundation Trusts

Weaker Trusts could not meet the financial criteria for Foundation status and 99 did not do so by April 2014, the target date for all Trusts to become FTs. Often these had major Private Finance Initiative (PFI) problems. Many more had internal management issues which might not show in the statistics but, because of poor leadership, might be an accident waiting to happen. Some 50 Trusts hoped to become FTs if they received transitional financial support. In 2011/12 they asked for at least £352 million to help them meet Monitor’s financial requirements. Andrew Lansley said such applicant Trusts would have to demonstrate that their problem was: “exceptional and beyond those faced by other organisations”; “historic and that they have a clear plan to manage their resources in the future”; “that they were delivering high levels of annual productivity savings”; and that “they delivered clinically viable, high quality services”. The biggest demand, for £93.5 million, came from a group of non-FTs – Barts and the London, Whipps Cross and Newham Trusts.

The NHS Trust Development Authority (TDA) later subsumed into NHS Improvement

Established in 2013 as a special health authority, the NHS TDA was responsible for those Trusts unable to achieve foundation status and for helping those who might. It grew rapidly, staffed largely by people who had commissioned services rather than by ex-managers. The TDA believed that, of the remaining non-FTs, many were unlikely to be able to stand alone.

Laggard Trusts were groomed to apply. The process was streamlined and included an early inspection by the Care Quality Commission (CQC); a ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ report was mandatory and the bar to FT status was perceived to have been raised. A rump of nearly 100 Trusts were unlikely ever to be shepherded to FT status and it became increasingly likely that a significant number would end in “special measures” – a failure regime. The TDA became essentially a performance manager mobilising outside staff to assist Trusts whose performance was deficient. Every failing Trust had a different problem requiring different types of assistance.

Bail-out funding continued to be needed and became a function of the TDA, which received bids from non-FTs for £370 million in 2012/13. A significant proportion of such Trusts had no clear plan for sustainability. David Nicholson, on leaving the post of Chief Executive in 2014, said that the policy that all Trusts should become FTs was not going to work. Alan Milburn who, as Secretary of State for Health had introduced FTs, thought that all Trusts should be authorised within three years, and Monitor and the TDA should be combined and charged with helping them. In 2015 it was announced that the TDA and Monitor would be merged and jointly led as NHS Improvement, chaired by Ed Smith and with Lord (Ara) Darzi as a non-executive director. Within this would be a new Patient Safety Investigation Service, based on the principles of the airline industry, and subsuming existing patient safety systems.

Monitor (subsumed into NHS Improvement in 2015)

Monitor’s traditional role had been to authorise FTs, ensure compliance with their terms of authorisation, and to aid ‘provider development’. Following the passage of legislation, Monitor’s core duty expanded to become a regulator for all NHS-funded providers, not just FTs, regulating prices for NHS services, and preventing anti-competitive behaviour against patients’ interests by absorbing the National Cooperation and Competition Panel (CCP). Monitor would ensure that Trusts remained financially sound and well governed.

Monitor not only licensed and regulated NHS FTs, but also licensed not-for-profit and private organisations providing NHS-funded care. It looked at potential breaches of the principles of co-operation and competition – for example, proposed mergers to ensure that a monopoly situation did not arise. When PCTs were told to give up the management of community health services, it examined the bids, and proposals to merge Trusts were examined to see whether alternatives existed within 30–40 minutes driving time. Reviewing in 2013 a proposed merger of head and neck services in Bristol, Monitor felt that the clinical advantages did not outweigh the loss of patient choice.

Whenever commissioners are considering proposals which would reduce the number of providers they should consider the impact that might have for patients. For some services there will be clear clinical evidence to support limiting the number of providers. In other circumstances there may be advantages to having a number of providers. Where the number of providers is limited the process for choosing the providers should be designed to achieve the highest quality and most efficient services for patients and taxpayers, and should ensure that the incentives for improving quality and efficiency are maintained in the longer term. (para 342)

Similarly the merger of two FTs, (Bournemouth/Christchurch and Poole) was blocked because it would reduce patients’ choice, although the Trusts felt it essential to maintain sustainability. In retrospect, both the Department of Health and Monitor thought the outcome unsatisfactory. Stephen Thornton, Deputy Chairman of Monitor, said the competition arrangements were a “bonanza for lawyers and consultants”.

To simplify FT authorisation, the CQC and Monitor integrated their requirements. The Department of Health had powers to direct Monitor should the need arise, and the CQC could direct Monitor to put a Trust into special administration on the basis of quality of services. Where competition between providers was impracticable, as in the case of community and mental health services, competition might exist to provide the service, rather than to provide a second and competitive one. Monitor would guarantee the provision of essential services if providers failed. In 2016, Monitor was integrated with the TDA to become NHS Improvement.

NHS Improvement

Inaugurated in April 2016, NHS Improvement integrated the main functions of Monitor and the TDA. Chaired by Ed Smith, NHS Improvement rebranded, changed the board and chief executive, re-laid the landscape of health care, remodelled regulation, redesigned care delivery along the lines of new models of care, restructured their supporting mechanisms on a subregional basis, merged two organisations, reappraised their workforce, and cut their budget.

Local authorities

Local authorities once again had a significant role in the provision of health care, for example, they were responsible for screening programmes. Because of the inter-relationship of health and social care, £1 billion was transferred from the NHS to them. There were three key areas where the Department of Health wanted to see transferred funding targeted: the protection and development of preventative services; programmes that brought health, economic and social benefits to communities; and the integration of social care and NHS services. Suspicion that this money was used by some local authorities to plug other holes in their budgets led to the examination of this policy.

Healthwatch

A new statutory body called Healthwatch England, an operationally independent committee of the CQC, would have responsibility for strengthening the voice of patients. Local branches of Healthwatch replaced Local Involvement Networks (LINks) and were funded by local authorities.

Health and Wellbeing Boards (new bodies from 2013)

Health and Wellbeing Boards aimed to improve the co-ordination of commissioning across NHS, social care, and related children’s and public health services. Their core membership was defined, and the Department of Health left it to local authorities to decide how they established the boards. They would be public health oriented, developing their own statistical basis. The boards involved local authorities, CCGs, the local patient-based organisation, Healthwatch, public health, social care and children’s services leaders joining together to assess what health and care services local people need, and agree on how they could best work together. Widely welcomed, their impact and influence was variable and generally limited.

Arms-length bodies

Liberating the NHS, Report of the Arms Length Bodies Review reviewed the functions of many bodies and confirmed the continuing existence of some, for example, Monitor and the CQC.43 Others were scheduled for run-down. The Health Protection Agency and the National Treatment Agency for Substance Abuse became part of Public Health England, an executive agency of the Department of Health.

Health and social care sharing

For several years, think tanks and political parties had seen joint working between health and social care services as essential if people, in particular the aged and those with chronic problems, were to be kept well and independent as long as possible. Small experiments had taken place locally as in Torbay. But in February 2015, a radical Memorandum of Understanding was signed by NHS England, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority and the 12 local CCGs and was supported by NHS providers. (document). It would cover the entire health and social care system in Manchester, a combined £6 billion budget. It included adult, primary and social care, mental health and community services, and public health. Coming into partial effect in April 2015 and full effect in 2016, Simon Stevens said that the landmark Memorandum required no legislation and charted a path to the greatest integration and devolution of funding since 1948. Supported by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the agreement was welcomed on all sides.

Part of a far wider devolution of planning, from April 2016, power to manage the £6 billion budget to manage the health and social care budget was devolved. FTs surrendered their autonomy. GPs were no longer independent businesses but part of locality focused hubs, and GPs would be leaders in local care organisations running primary, community, social and mental health care services. Manchester would do things differently, but national strategies for health services would still apply. The changes would be evaluated and NHS could take back control if necessary. The mergers of CCGs and the establishment of ten local care organisations responsible for delivering primary and community services, built around populations of 30,000–50,000 people, showed it was practicable to change organisational models. While substantial annual transformation money of £150 million for five years was available, the providers were on course for a deficit of £34 million in 2017/18.

A series of smaller pilots announced in 2015 would permit some local authorities and CCGs to integrate particular services within a common budget.

Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs)

In 2014, against the background of falling resources, Trusts increasingly in deficit, and fragmented commissioning responsibilities, NHS England began a quiet reorganisation possible within its remit, without legislation or publicity. The NHS Five Year Forward View was published, emphasising prevention, integration of services and putting people in control of their health, and describing new care models. Most models involved closer and different relationships between providers, NHS Trusts, and local authorities. The two principles now appeared to be collaboration, rather than competition, and a move towards integration of health and social services to aid the care of the elderly and those with disabilities and long-term problems. While the 2012 Act had removed Strategic Health Authorities as regional-level planners, a work-around without legislation was introduced in the form of Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs). In December 2015, the NHS Shared Planning Guidance 16/17–20/21 outlined a new approach to “ensure that health and care services are built around the needs of local populations”. STPs were to be produced by the end of 2016, using plans and financial templates, with the triple aim of improving health, improving care and saving money. Forty-four ‘footprints’ were defined, the areas and local leadership often being determined by NHS England and its four regional divisions. The coterminosity that might have been expected in a joint enterprise was not apparent. STP footprints varied in size from 330,000 to over 2 million, and involved many different organisations, each with its culture and priorities. There had been limited public involvement in the process, but there had also been limited involvement of GPs and local authorities in some areas.

STPs had no legal framework or formal accountability and their development was hindered by the lack of a budget, or of free managerial time at the senior levels required. As a driver of strategic planning, STPs were the ‘only game in town’. It was assumed that they would feed into operational planning, though they had been created outside any structural framework. The STP process was reviewed by the King’s Fund in 2016 and their further analysis of 44 of the plans in 2017 fleshed out the nature of the proposals. Most included changing the role of acute and community hospitals to reduce the number of hospital sites and beds, centralise some emergency departments and acute services on fewer sites, and reconfigure the way that specialised services are delivered. STPs describe ambitions to improve care in maternity, mental health, learning disabilities, and children and young people’s services – depending on local needs and priorities. A wide variety of measures to improve productivity and efficiency were included. Many were dependent on capital spending when there was little money to be had. Some proposed shared governance of health and social services. Among the challenges faced were the problems of change in the absence of capital to develop community services or new centralised hospital facilities. There was little evidence that reconfigurations saved money. The ‘footprints’ covered by the STPs were encouraged to appoint a single accountable officer, a difficult position as such officers had neither the authority nor (in most cases) the funds to change matters.

The Department implied that the services covered by an STP might evolve into an Accountable Care Organisation (ACO), a term derived from US attempts to improve health system efficiency. ACOs were characterised by an alliance of providers that collaborate to meet the needs of a defined population. These providers take responsibility for a budget allocated by a commissioner (or alliance of commissioners) to deliver a range of services to that population. They work under a contract that specifies the outcomes and other objectives they are required to achieve within the given budget, often extending over a number of years. The King’s Fund, whose definition this is, published a series of reports – Making Sense of Accountable Care – on pilots as they developed. ACOs might cover social and local authority services, bringing into the system some of the known systemic causes of ill health – housing and education.

Finance and the emerging crisis

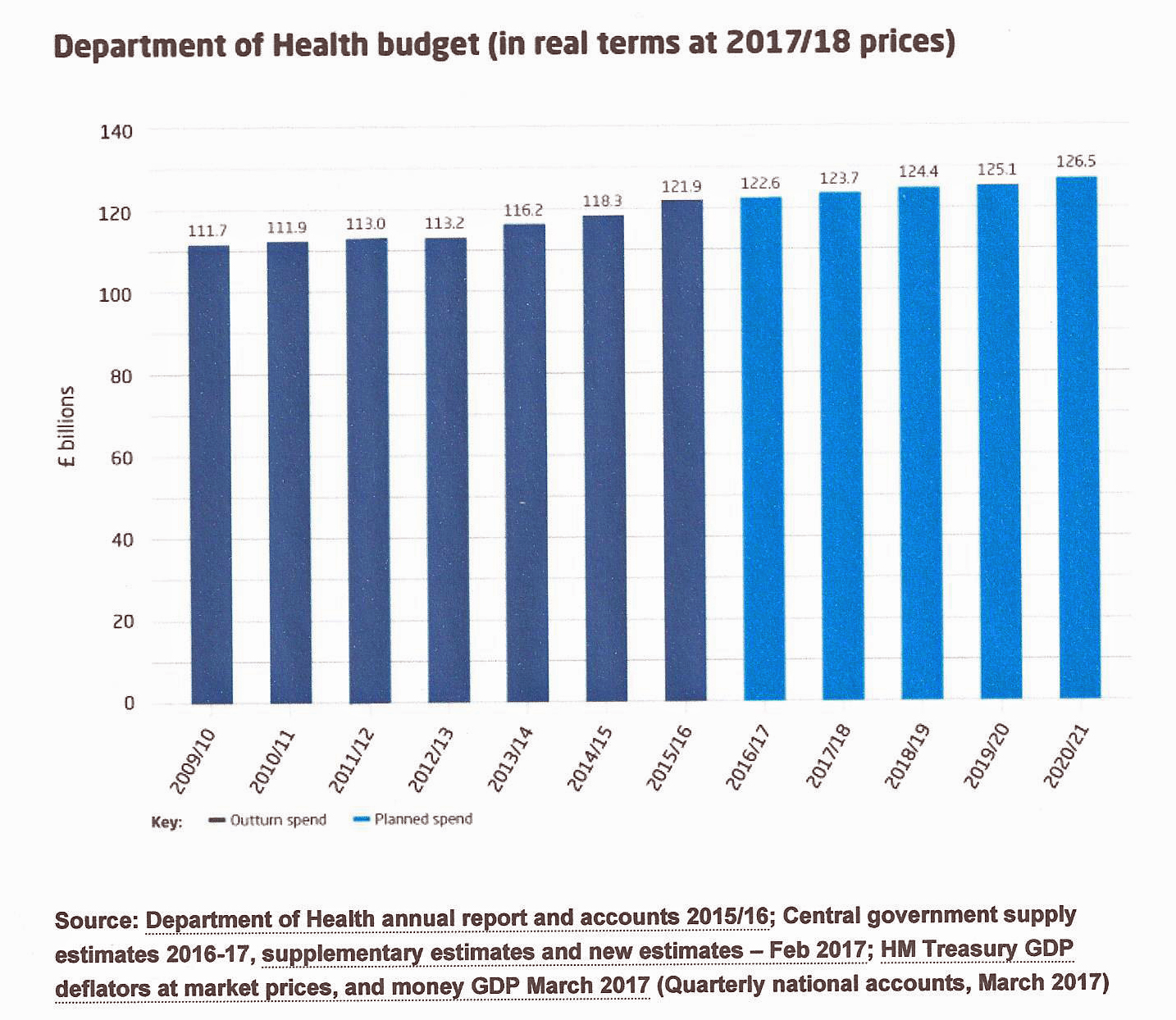

Money has often driven change in the NHS. After the Blair ’Breakfast with Frost’ (2000) the growth rate accelerated dramatically. When the economic crisis struck in 2008, the growth rate was cut. This triggered financial crises in the service and the future outlook was bleak.

After the previous high growth rate, the projected rise in the NHS budget in real terms from 2008/0 to 2010/11 had been 1.9 per cent a year but, as the financial crisis bit, and billions were poured into banks, projections were reduced to 1.2 per cent between 2011/12 and 2013/14. Public debt would overhang services for ten years or more. David Nicholson wrote:

I first set out the broad challenge the NHS was facing in May 2009 in my publication, The Year: NHS Chief Executive’s Annual Report 2008/09. At that stage we estimated that efficiency improvements of £15–20 billion would be required in the three years between 2011 and 2014. This was based on a broad comparison between the pressures facing the NHS (for example, from pay, prices and growth in underlying demands) and likely levels of funding growth. The range was deliberately a broad one at that point, given the uncertainties, particularly around the level of funding the NHS would receive. Subsequently the Spending Review of 2010 confirmed funding levels for the four-year period of 2011/12 through to 2014/15. Following this we therefore refined the efficiency challenge as up to £20 billion over this four year period.44

The ‘Nicholson challenge’ implied an increase of 4 per cent in productivity annually, and no real-terms increase in NHS budgets. It reflected independent analysis that suggested the NHS would need to sustain large annual productivity increases in order to maintain the quality of its services when health spending was bound to rise more slowly.45 Never had such productivity increases been achieved before. Four chief executives in the London area resigned within a week for financial reasons, including the Royal London and West Middlesex hospitals.

A report for the Department of Health from McKinsey in March 2009 was leaked to Health Services Journal in September and ultimately published by the Conservative/LibDem government in June 2010.46 McKinsey implied that, to achieve its planned £20 billion savings by 2014, the NHS in England would need to slash its workforce by 10 per cent – 137,000. The report revealed the brutal reality of the cost to the NHS of the collapse of the banking system. It recommended a range of “potential actions in the next six months” including a recruitment freeze, an immediate reduction in medical school places to avoid oversupply and an early programme to encourage older GPs and community nurses to make way for “new blood/talent”. Acute services would take the brunt of the cuts. Some savings could come from clinical efficiencies, but not enough. The report (that took the form of a slide series) had the Department of Health’s support and had been shared with SHAs and senior management. McKinsey recommend a nationally-enabled programme delivered through the SHAs and PCTs to drive through efficiency savings. When leaked, the Department attempted to disown the recommendations. Andy Burnham, then the Secretary of State, said “the McKinsey work… is not in any sense an NHS plan of action. They are just making some suggestions which will be looked at with many other ideas.”

Some calculations of the scale of cutbacks – over 50 per cent of London acute hospital work – seemed infeasible. Many hospitals had historic difficulties in balancing their books and this put the quality of care in jeopardy. Over five years, almost a billion pounds was spent keeping some 18 Trusts afloat.

In June 2010, the government appointed an Independent Challenge Group (ICG) of civil service leaders and external experts, to examine the spending review process. In September the group warned that NHS savings might not be achievable and government might face either a growth in waiting times or the need to inject billions more into the NHS.47 Following the Spending Review in October 2010, it was announced that the NHS budget would rise in real terms by 0.1 per cent, keeping the promise to protect the NHS budget, (just).

It was suggested, with little evidence, that massive savings could be achieved by the transfer of care from hospital into the community, polyclinics or federated practices. Small sums were made available for the Transforming Community Services (TCS) programme. Trials showed that telemedicine might make it safe to transfer care of respiratory disease into the community, but there was no evidence of cost saving. Staff of a higher quality might need to be employed in the community setting. The operating framework for 2010 had required a substantial reduction in management costs in PCTs and SHAs, and Acute Trusts would be paid only 30 per cent of tariff costs above the agreed activity level of the previous years. Nor would tariffs be increased for inflation. Health Minister, Mr O’Brien, told Parliament in March 2010 that blaming the economic situation for the cuts was “nonsense”. A manager responded:

Ministers say you must save £20 billion. Ministers then get upset when the NHS puts forward plans to save £20 billion because it involves shutting beds and reducing staff numbers. How else does one save substantial sums of money in a labour-intensive industry? We could of course keep all the beds open and just cut staff – but only if they want a Mid Staffs to pop up every other week.

A pay-freeze for consultants, GPs and senior managers was imposed in 2010, and subsequently for all staff. Financial directors were optimistic that savings targets would be reached in the early years but, when the pay freeze ended, another £500 million would be added to costs. Savings in management costs with restructuring would not be recurrent. Patient care was at risk. Yet the Nicholson challenge was likely to extend for many more years and inevitably this would lead to major reductions in staff. Roy Lilley, in his blog, said that the NHS had been hit with the double whammy of unprecedented and unpredicted demand and the need, like all public services following the credit crunch, to live within its means. The NHS was making its money work at least as hard as the staff on the front line. For 20 years, Jack Wennburg, in the USA, had suggested that reduction in the variations in service provision would save money – though there was little sign of major success in altering the differences, even in his home states. The Dartmouth Health Atlas identified conditions where the rate of surgery differed greatly, for example, osteoarthritis of the knee.48 If there was a £20 billion shortfall in a labour-intensive service, what was the answer? The BMJ published articles on savings that could be made without harming services.49 They did not amount to much.

Evidence of stringency soon appeared. The proposed North Tees Hospital was cancelled. PCTs increasingly controlled the elective admissions for which they would pay, and reviewed procedures, including IVF and reversal of sterilisation and vasectomy and endoscopic procedures of the knee joint, lumbar spine procedures for back pain, removal of breast implants and breast reduction to relieve symptoms.50 When commissioners imposed strict criteria for payment, Trusts might allow patients to purchase care that did not qualify as “self-funded patients”. Such services might include IVF, inguinal hernia and varicose vein removal. The Trusts charged a sum lower than normal private care, perhaps standard NHS prices.

A pay freeze on NHS staff and tariff cuts of 1.5 per cent in 2011/12, a further 1.5 per cent in 2012/13, 1.3 per cent in 2013/14 and 1.5 per cent in 2014/15 was designed to achieve target savings. There was no longer money to reduce waiting lists and they might be allowed to get longer to save money – PCTs sometimes imposed minimum waiting list times. Most Acute Trusts predicted the loss of a substantial number of posts. Whipps Cross in east London, facing a £4.5 million deficit, urged staff to “sacrifice” some of their annual leave or do unpaid work to save money.51 When the reconfiguration of services was seen as a financial salvation, it took time, and the savings did not always materialise. Some hospitals might appropriately close their A&E and move from an acute role to elective work – a regular stratagem to save money – but a temporary embargo on reconfiguration by Andrew Lansley, political pressure from MPs, and public objections made change near impossible.

Between 2009/10 and 2014/15 English NHS funding rose by £14.9 billion from £98.4 billion to £113.3 billion, an increase of around 0.8 per cent in real terms on average, an additional £890 million per year. Yet a looming ‘black hole’ of perhaps £30 billion by 2020 was emerging; Both Trusts and FTswere increasingly in deficit. In the first quarter of 2014, 86 out of 147 FTs reported one and in December 2014 an additional £2 billion annually was found for the service. The Trusts that did not have FT status also reported a combined deficit. Approaching the 2015 election, both parties promised that there would be more money for the NHS; neither could say whether it would be “adequate”. In 2014/15 providers had an aggregate deficiency of over £800 million and predicted worse to come. The King’s Fund reported on the performance of the service under the coalition, finding that it had held up well for the first three years, but had now deteriorated with waiting times higher, and several key targets missed. Public satisfaction, however, remained high.

By 2015 the number of Trusts predicting annual deficits rose – almost half were in deficit. In an autumn spending review, the government made an additional £4 billion available but the National Audit Office (NAO) believed that Trusts as a whole being in deficit, additional money should be used to restore solvency, not to embark upon new initiatives (for example, the 7-day hospital). By early 2016, the proportion of Trusts probably in deficit, some four out of five, and the total deficit likely, led to warnings that, even after Mid-Staffs, head counts could not be regarded as inviolable, and remaining within budget was not ‘optional’. We had moved from a post-Francis accent on quality to recognising that a balance had to be struck between finance and quality. NHS Improvement, the successor to Monitor and the Trust Development Authority, said that “quality and financial objectives cannot trump one another” and that the task of providers was to “deliver the right quality outcomes within the resources available”. In 2015/16 the aggregate deficiency was £2.45 billion and 85 per cent of Trusts were in deficit. In November 2016 the NAO repeated its view (Financial Sustainability of the NHS) of the severe problems faced, and that the short-term measures employed were not a sustainable answer. The pay freeze on NHS staff started to be relaxed in 2018. As the 70th anniversary of the NHS approached in 2018, the government promised an increased growth rate for the NHS over the coming five years, something a little below 4 per cent.

The allocation system

Each year the Department of Health traditionally stated the resources for the NHS and national priorities in its Operating Framework.52 From 2010, this was supplemented by the Outcomes Framework, part of government’s intention to move the NHS away from focusing on process targets to measuring health outcomes. Subsequently a ‘funding envelope’ was agreed between NHS England and the Department of Health alongside the mandate that outlined what the expectations were. For 2013/14 this was £95.62 billion.53 NHS England had to determine how to allocate funds between the main areas of commissioning spend (public health, primary care, CCGs, specialised/health and justice/armed forces and the integration-transformation fund), how to allocate funds within each stream, that is, the distribution between localities, and the pace of change associated with any change in allocation policy. A parliamentary note gave figures for allocations since 1974.54