If someone suggests using years lost to death and disease as a way to measure health outcomes, it is likely to conjure up images of older adults dying a few years earlier than predicted, or living their twilight years in poor health. But the construct has lots to offer us in measuring and understanding trends in young people’s health too, even if it is not an immediately intuitive notion.

We’ve used Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in our new report looking at international differences in young people’s health outcomes, and here we explain in a bit more detail how they work for this age group.

What is a DALY?

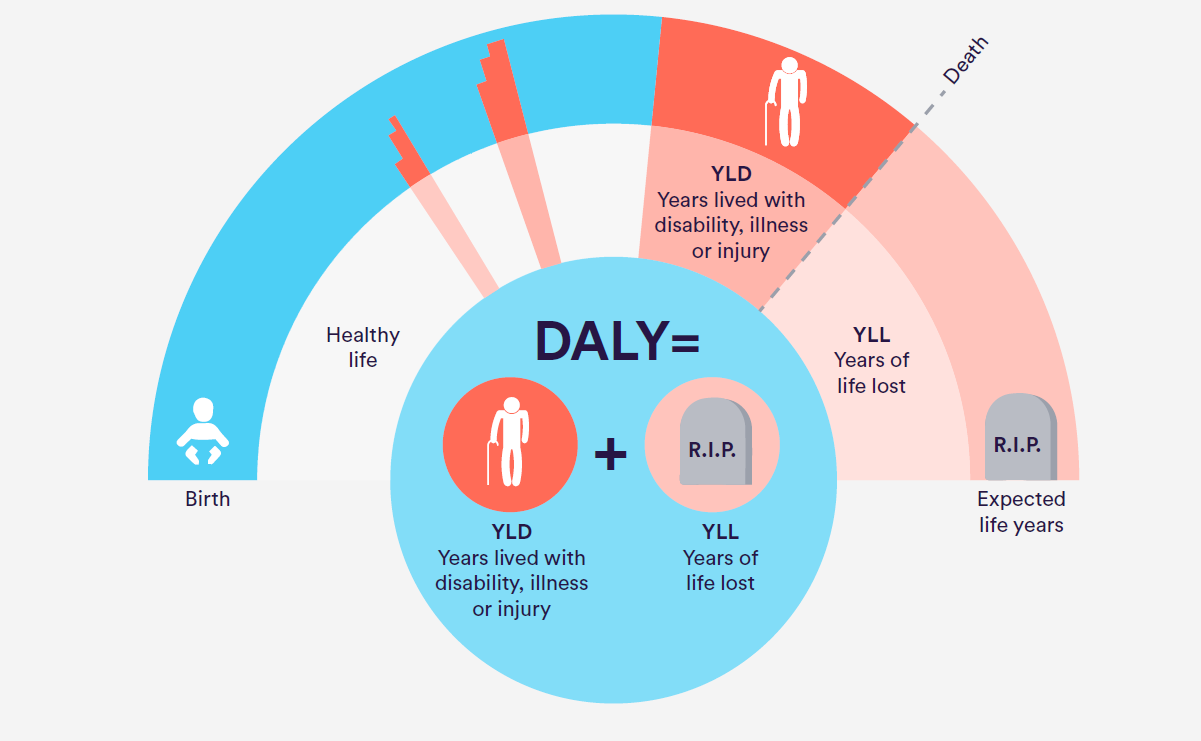

The DALY estimates how much disease affects (‘burdens’) the life of the population. It is the primary metric used by the World Health Organization to assess the global burden of disease. DALYs combine in one consistent summary measure the burden from (a) mortality: years lost because of premature death due to disease; and (b) morbidity: years of life lived adversely affected by disease.

Time lost to premature death is compared to a standard life expectancy (usually 80 years for men and 82 years for women). DALYs measure the difference between a current situation and an ideal scenario where everyone lives in perfect health up to the age of the standard life expectancy.

If we take the example of a cohort of 15-year-old boys, the ideal situation is that they all will live to 80, completely free from illnesses like diabetes, asthma, cancer or obesity. The death of a 15-year-old boy – in a road traffic accident, for example – with no years lost to disability (as the accident was sudden and he was previously in perfect health) would account for 80 minus 15 = 65 years lost, or 65 DALYs. At its simplest level, one DALY equals the loss of one healthy year of life due to death – it’s equivalent to dying one year early.

Complicating factors

Things become a little more complicated when we add in years lost to disability, which is partly because not all diseases are equal in how they affect your day-to-day life. The impact of each condition or disease is weighted differently, based on how much the average person thinks any given disease affects an individual. Years lost to disability thus relies on these ‘disability weights’.

For example, a year spent living with partially controlled asthma is estimated to be about 3.6% as ‘bad’ as a year lost to death, because the disease weighting for a year of partially controlled asthma is 0.036. To put it another way, living with asthma for 27.8 years (1/0.036) is equivalent to dying one year earlier than expected, in terms of a disease’s impact using this method. By contrast, living with schizophrenia has a disability weighting of 0.576, which is much higher than asthma. One could live with schizophrenia for the equivalent of only 1.7 years (1/0.576) to die a year earlier than expected – so a significantly bleaker outlook than for those with asthma.

A 15-year-old boy who lives for five years with an incapacitating disease such as severe epilepsy, which is weighted at 0.4, might be judged to have lost the equivalent of two years of healthy life overall because of this disability (five x 0.4). If he then dies of it at the age of 20, the DALY rating will be a combination of all the years lost (80 minus 20 = 60), plus the equivalent of two years lost to illness, giving a DALY of 62 years of healthy life lost due to the condition.

When do DALYs come into their own?

DALYs are most useful for measuring the burden of disease for the population. The whole population of young people aged 10-24 has millions of healthy life years ahead of them, and death or even severe incapacitation are rare. So we need a summary measure that helps us to visualise how big the impact of disease is across all young people, compared with them all living to their 80s in perfect health.

That is usually done by giving the DALY rate for 100,000 healthy life years. If we took a sample of 100,000 of all the possible healthy years that today’s 10–24-year-olds are going to live, we would expect around 10,000 years to be lost to all causes of ill health (“all-cause DALY rate”). DALYs can be calculated in this way for all diseases together, or separately for each individual disease so they can be compared.

And it is their use in comparisons that is most helpful. By using DALYs that are comparable across populations, we were able to show in our new report that the UK’s young people lose more years than they should to long-term health conditions such as type 1 diabetes.

That kind of information is critical in helping us to focus our attention on improving health services for this age group, and – ultimately – increasing the years they live without death or disability.