Key points

- Regional variation in NHS staffing levels can lead to inequalities in people’s ability to access services, care quality and health outcomes. For example, the number of patients per GP varies more than two-fold between local areas, from 2,804 in Hull to 1,318 in Wirral as of June 2021.

- Supplementary payments (or ‘recruitment and retention premia’) have been used by NHS organisations across England over the last few decades and can be designed to attract or keep staff working in certain services, locations or specialties. They present an opportunity to ensure a fairer distribution of staff. We found that 1 in 174 hospital and community staff currently receive specific recruitment and retention premia, accounting for some £28 million annually.

- NHS funding allocations are adjusted to reflect increased reliance on agency staff, higher vacancy and turnover rates and differences in staff productivity in areas with more challenging labour markets. We estimate that this staffing adjustment had the effect of redistributing £1.5bn of trusts’ total operating income in 2016/17, with Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust receiving £37m (3.4%) less and Barts Health NHS Trust receiving £107m (7.8%) more than they would without these adjustments.

- Pay supplements such as ‘London weighting’ can also be considered a form of recruitment and retention premia. Some £986 million was spent on staff who received a ‘high cost area’ supplement such as this in 2021.

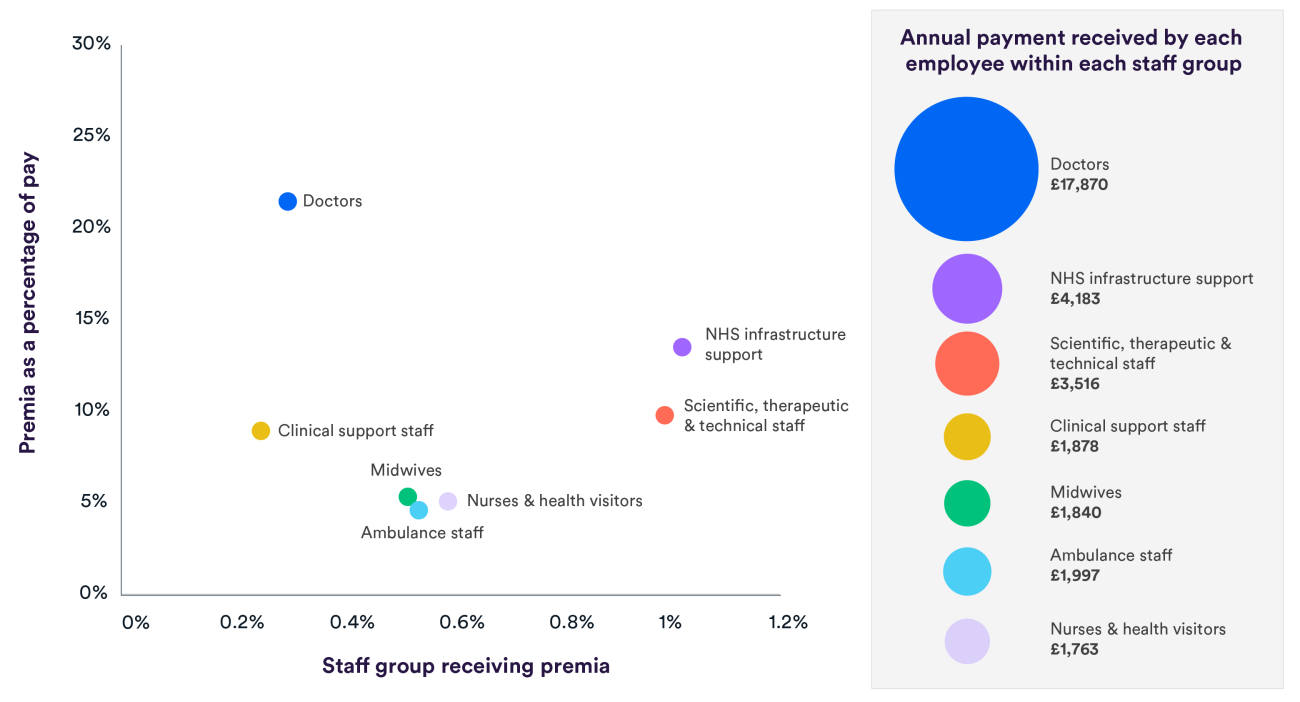

- Some staff groups are much more likely to receive recruitment and retention premia, and the average level of those premia also varies considerably across groups. On average, doctors receiving premia get nearly £18,000 in premia payments – that’s 21% of their mean annual earnings. In contrast, clinical support staff receive around £1,900 a year, or 9% of their mean earnings. There is no evidence to suggest that this variation is optimal.

- There is a lack of published evaluations on how cost-effective pay supplements have been for recruiting and retaining NHS staff, and ‘London weighting’ has not been reviewed in nearly two decades. Further work should be done to understand what the appropriate level of compensation would be for living and/or working in or around London, as well as in the other areas of the country that face higher living costs.

We identified some key questions which should inform any further evaluations of pay supplements:

- Are premia schemes attractive for prospective applicants in the short-term?

- Do they increase staff retention in a given area in the longer-term?

- Do the benefits of these schemes outweigh the costs (including in comparison to non-pay benefits)?

- What are the unintended consequences of premia on other areas, staff groups and characteristics?

What are recruitment and retention premia?

Recruitment and retention premia are additional pay designed to attract or keep people working in certain services, locations or specialties. They are used across different parts of the public sector in the UK, including local government, education, justice, and the health sector. Despite this prevalence, little is known about the impact of premia schemes on staffing levels.

While NHS workforce gaps can be filled temporarily, this can be a significant financial drain, with some £2.5 billion spent on agency staff in 2019/20 (NHS Workforce Alliance, 2021; NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021). The exact extra cost of using agency staff is unclear, but others have suggested that it is around 20% more than directly employing staff (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2018) – equating to around £420m per year. Meanwhile, some general practices regularly pay up to £800 per day for locum GPs.

Recruitment and retention premia present an opportunity to ensure a fairer distribution of staff. This in turn could reduce inequalities and improve patient care. However, there are risks to their use, such as the potential to create unhelpful competition between providers. They could simply shift staffing shortages to other regions – or, if they don’t change behaviours, they may even waste money. Localised premia also risk creating a “cliff-edge”, which can influence employers to either underpay or overpay in neighbouring areas (Department of Health, 2012).

Staff who are not employed on NHS contracts with defined pay structures, such as locum GPs, may receive variable payment rates depending on local market conditions, but in this briefing we focus on pay supplements given to those employed on the Agenda for Change contract, NHS medical contracts or the very senior manager NHS contract. Pay is just one of the mechanisms that can incentivise staff to join or stay in their role. Other, non-financial incentives such as offering flexible working patterns are also important.

How are recruitment and retention premia used in the NHS, and how much do they cost?

National and local recruitment and retention premia are used across NHS organisations in England (box 1) to help solve issues of the undersupply of staff in specific areas (NHS Pay Review Body, 2020; NHS Employers, 2021).

Box 1: Description of some key current recruitment and retention premia

High cost area supplement (‘London weighting’)

All Agenda for Change staff in ‘inner’, ‘outer’, and ‘fringe’ London at maximum rate of 20% of basic pay, up to £7,097. Supplement for doctors and dentists up to £2,162. First introduced in 1974

Local recruitment and retention premia

Offered by individual trusts with value of up to 30% of basic salary (or starting salary for consultants) for medical consultants (since 2003), Agenda for Change staff (2004), and very senior managers (2013)

Flexible pay premia

For doctors in training on specific programmes (specialties) up to a value of £7,146, introduced in 2016

Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme

GP trainees in hard-to-recruit, deprived or rural/remote areas, since 2016. £20,000 one-off payment

New to Partnership Payment

Offered nationally to healthcare professionals taking up a partnership role in primary care since 2020 and worth up to £27,000

Notes: See Appendix 1 for a more detailed table. The Agenda for Change contract includes all staff groups with the exception of doctors, dentists, very senior managers and staff employed in general practice.

While there is no comprehensive figure for the costs of such premia, it is clear that some represent a significant expense, although levels vary considerably across mechanisms. The largest form of premia by far are high cost area supplements, which are in place to reflect the higher cost of living in London and its surrounding areas – costing £986 million.1 Recruitment and retention premia across hospital and community health staff costs considerably less, at around £28 million2 per year, with these premia and supplements comprising 2.3% of all trusts’ expenditure on salaries and wages. Although there is a lack of comparable data in primary care, premia given to GP trainees cost up to an estimated £37 million a year.3

However, recruitment and retention premia expenditure is low compared to the amount of funding allocated to reflect different local labour markets. Funding received by NHS trusts and commissioners is adjusted to reflect local, unavoidable costs of providing services (known as the market forces factor), with around two-thirds (63%) of this adjustment attributable to staff costs. The stated purpose is to account for variations in employment costs, including indirect costs such as higher turnover and vacancy rates (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021b).

For non-medical staff, the adjustment is based on the pattern of wages within geographies (Travel to Work Areas) as defined by the Office for National Statistics, which is intended to reflect local market conditions. For medical staff, the adjustment accounts for the additional cost of London weighting only, implying that there are no further unavoidable costs from staff turnover and vacancies. The range of effects of this adjustment on income is equivalent to a £37m (3.4%) decrease for Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and a £107m (7.8%) increase for Barts Health NHS Trust.

Barts Health NHS Trust also experience the largest increase in relative terms, while Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust have the most significant decreasing effect compared to total operating revenue, receiving 6.9% (£27m) less than would be the case without the adjustment.

A similar resource allocation adjustment – the Carr-Hill formula – exists under the main general practice contract (General Medical Services). This also accounts for geographical variation of staff costs.

Who makes decisions on when premia should be used in the NHS?

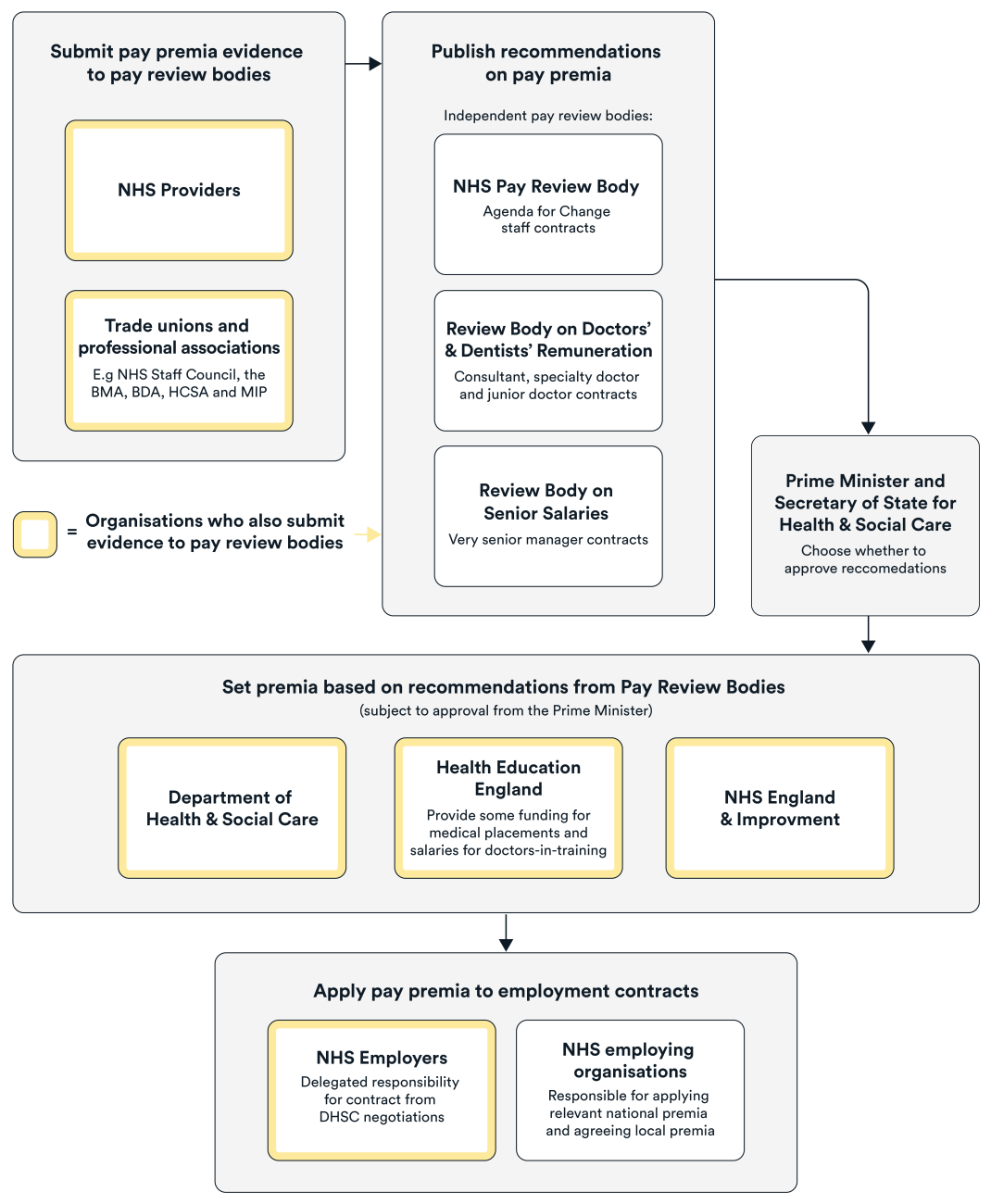

Those in charge of making decision on premia use in the NHS varies for the different contracts that staff are employed under. The NHS pay review bodies analyse evidence and provide pay recommendations to the government, which can include recommendations on pay supplements relating to the contracts that cover all directly employed staff (Figure 1). However, the NHS pay review bodies do not make recommendations on pay supplements unless specifically invited to do so by the government. Depending on whether recommendations are accepted by the government, these are then fed into the contractual terms and conditions. In addition to these national arrangements, individual NHS employers have the employment freedom to use local premia.

Decisions can also be made outside of the annual pay review process. For example, the Agenda for Change contract (used by most NHS employing organisations) was developed by employers, membership organisations and government through nationally or locally agreed changes to employment contracts.

Although the design of national and local premia has largely remained the same for all staff since their introduction, the proportion of staff receiving such payments has fallen. This decline is largely attributable to the withdrawal of all national schemes for Agenda for Change staff in 2011 and their conversion, where deemed appropriate, to local pay supplements (NHS Pay Review Body, 2020). Moving to a local premia model was supported by NHS bodies, who argued that employers should use such payments in response to local market pressures (Department of Health, 2012; Brown and others, 2017). While most decisions to use premia are made locally, there are still nationally led schemes in place, such as the Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme for GP trainees (see Appendix 1).

How do recruitment and retention premia vary between staff groups?

As at June 2021, 0.6% of all NHS hospital and community staff received national or local recruitment and retention premia, whereas 1 in 5 (20%) staff received high cost area supplements. However, the proportion of those currently receiving recruitment and retention premia varies by staff group. For example, infrastructure staff are three times as likely to receive national or local premia (excluding London weighting) than clinical support staff (1.0% compared to 0.3%).

The amount afforded to staff also differs, both in absolute terms and relative to annual earnings. While doctors earn the most out of all staff groups in absolute terms (with mean earnings of £83,266 per year), the mean premia as a proportion of their mean earnings afforded to this group is also the highest (21% of mean earnings, equivalent to £17,870) (Figure 2).

In addition, consultant doctors and dentists and academic GPs are eligible to receive performance-related bonuses known as national Clinical Impact Awards (CIAs). Although not strictly considered a form of premia, one of the aims of this mechanism is to retain staff (Department of Health & Social Care, 2022), though there is little evidence that these awards have improved retention. Both national and local schemes (known as Local Clinical Excellence Awards) exist, with up to 600 national awards offered to eligible consultants, ranging from £20,000 to £40,000 a year. The value of local awards varies depending on when they were granted, but there is an expectation that employers will spend a minimum amount on these awards. This is a significant amount of money being offered to consultants – with CIAs and LCEAs costing £500m in 2011/12 (National Audit Office, 2013), yet no other such scheme exists for other NHS staff.

Premia payments should be set at a level that is sufficient to attract and retain staff, and that does not place unnecessary cost on the public purse. We would expect decisions to be made based on factors including staff shortages, retention issues and the cost of living. That said, there are other reasons why premia levels might vary, including differing attitudes towards pay incentives between staff groups. International evidence has shown that income was an influencing factor among doctors that signed up to receive premia in order to fill less popular specialty places (Vaughan, 2019). In contrast – although not directly comparable to the evidence cited on doctors – research into pay incentives for nursing shows that there was no evidence that the use of pay supplements would help solve recruitment and retention problems, nor has pay been a key motivator for nurses, although this may be changing (Brown and others, 2017; The Open University, 2019).

Differences in the terms and conditions set out in different staff employment contracts also affect how premia are applied between staff groups. Although high cost area supplements (also known as London weighting) in the English NHS were initially paid equally across staff groups, at £877 per year in 1986 (£2,324 in 2021/22 prices) (Hansard, 1986), the rationale behind its use and amount allocated is now different.

There are limits on premia set and defined by different pay review bodies (Table 1). All staff on an Agenda for Change contract are subject to a London weighting uplift – for example, a band 9 director of estates and facilities in an inner London trust is given an uplift of £7,097 per year. The NHS Pay Review Body states that this is due to the higher cost of living (NHS Pay Review Body, 2020). But the review body for doctors’ and dentists’ pay believed that London weighting should be in place only as a response to labour market shortages (Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration, 2007).

The Review Body on Senior Salaries went further and concluded that geographical pay differences were not appropriate for very senior managers in the NHS because recruitment and retention premia of up to 10% of basic pay can be applied to these posts. However, average earnings for these staff working in London was below the national average across all regions (Review Body on Senior Salaries, 2012; Review Body on Senior Salaries, 2021).

Contract |

Basic pay range (2021/22) |

London weighting (2021/22) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Agenda for Change |

£18,546–£108,075 |

£1,066–£7,097 |

Varies from 5% to 20% of basic salary, depending on location of organisation |

|

Doctors in training |

£28,808–£56,077 |

£38–£2,162 |

Rate varies depending on location of organisation and whether residence is provided |

|

Specialty doctors |

£45,124–£77,519 |

||

|

Specialists |

£79,894–£90,677 |

||

|

Consultants |

£84,559–£114,003 |

||

|

Very senior managers |

£89,500–£265,000 |

n/a |

n/a |

| Sources: NHS Employers (2021); NHS Employers (2021); Review Body on Senior Salaries (2021). Note: See Appendix 1 for a more detailed table. | |||

Some variation is to be expected, with previous research (albeit needing revisiting and updating) supporting the provision of area cost adjustments to help with nursing recruitment, but not for doctors (Health Economics Research Unit, 2009).

Given the differences between funding decisions and contractual conditions regarding premia for different staff groups, further work must be done to understand whether these differences are optimal, considering the labour market challenges for each staff group. This must be coupled with the consideration of the cost of living, particularly noting the large differences in absolute basic pay, as well as premia, between staff groups. Given that research has found that public sector employers are only up to 40% as responsive to area differences in costs compared to the private sector (Bell and others, 2007), and higher costs of living lead to increased leaver rates in acute trusts (Propper and others, 2021), there should be further research into whether pay supplements sufficiently compensate the various staff groups for these higher living costs.

How do supplementary payments vary between and within geographies?

Regional variation in staffing levels can give rise to inequalities in patients accessing care, the quality of that care, and health outcomes. These regional differences are starkly observable – for example, the number of patients per GP, even after accounting for need, varies more than two-fold between local areas, from 2,804 in Hull to 1,318 in Wirral as of June 2021 (Rolewicz, 2021). Given the well-established variation in NHS staff shortages between regions (NHS Digital, 2021), the use of premia to attract staff to different areas is also expected to vary. As previously mentioned, decisions to use premia are usually made locally in response to a specific labour shortage in that area. However, nationally funded schemes can also be used to target certain areas (such as the Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme for GPs). There are also some premia that apply across the whole country, such as the New to Partnership Scheme for GPs (see Appendix 1).

Although the current evidence is limited, just over a decade ago the proportion of staff receiving premia (excluding high cost area supplements) was particularly high in the South East (18.7% of all staff) and South Central England (15.7%), although this was mainly because a high proportion of nurses and maintenance staff were receiving premia. This was likely to be due to providing pay protection to some staff, which aimed to lessen the impact of changes to salaries after the introduction of new employment contracts (Department of Health, 2012). While not strictly focussed on premia, more recent research has found that the use of allowances and premiums – again, excluding London weighting – for nursing posts varies between regions, with those in London receiving the highest proportion (34%) (Propper and others, 2021).

There may also be differences in the use of national and local premia within regions, owing to, among other things, differences in attitudes of trust leaders towards paying for them. While all trusts are given the same flexibilities to use local payments, some may feel unable to justify their use, especially in the context of general funding pressures in trusts (Gainsbury, 2021). Different providers within regions will also face their own, unique recruitment and retention issues due to differences in size and type of trust, which will influence decisions on whether to use premia .

Geographical differences in supplementary pay also have a bearing on the distribution of high cost area supplements. Since the whole purpose of this type of payment is to provide compensation for those living in high cost areas, it is expected that this supplement would vary by location (see Appendix 3 for a detailed breakdown). However, geographical uplifts for the majority of hospital and community staff have not been reviewed in nearly two decades (NHS Pay Review Body, 2020). The cost of living has changed substantially during this time, and given that the rationale for this payment is based on high living costs, we would expect the payment to consider areas outside of London and its outskirts (ONS, 2021).

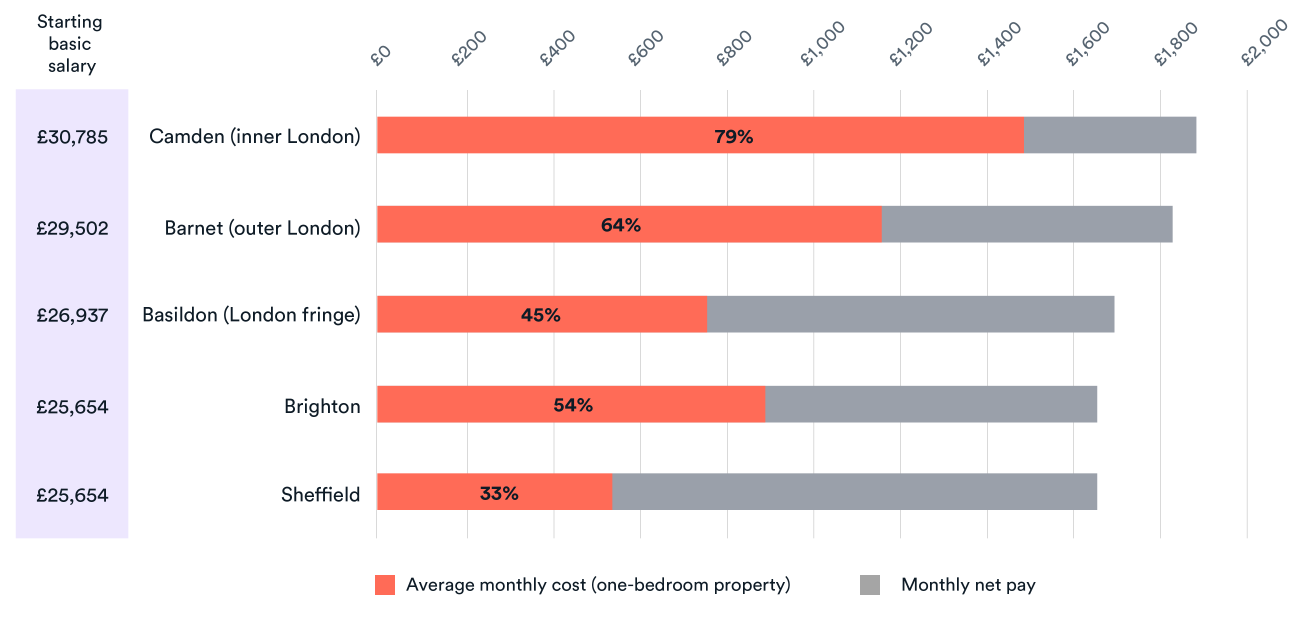

There are, of course, many factors affecting cost of living and the financial incentives and disincentives of working in an area. However, as an indication of how cost of living may vary, Figure 3 illustrates the differences in the geographical uplifts for a new nurse compared to the average monthly rent cost for a one-bedroom property. Such comparisons should be treated with caution given, among other things, the different accommodation options actually available.

Uplifts to salaries in inner and outer London, as well as the fringe areas, do not appear to offset the cost of living relative to areas without a high area cost supplement, such as Sheffield. Some staff in London, such as nurses, have a higher share of their earnings accounted for by allowances and premia, which provides some amount of additional compensation for the cost of living (Propper and others, 2021). However, the offer to those looking to join the NHS in London at lower-paid bands may still not be an attractive one. On top of this, recent graduates are more likely to have a student loan repayment plan (Bolton, 2021), which would further reduce their take-home pay once in employment. An additional problem is that other areas of the country with relatively high average rent prices (such as Brighton) are not eligible to receive additional payments based on the cost of living. Interestingly, the broadening of high cost area supplements to other regions was considered under a previous government, though with little supporting evidence and without any intention to increase funding – implying that money would be taken from those receiving the supplement in London and distributed more widely (Lazou, 2012).

Further work should be done to understand what the appropriate level of compensation would be for living and/or working in or around London, as well as in other areas that face higher living costs. However, the importance of local labour markets should not be underestimated, as different regions may respond differently to changes in pay (Crawford and others, 2015). Nonetheless, any increases or broadening of eligibility for high cost area supplements would need to be backed by funding from HM Treasury.

How effective are pay supplements at recruiting and retaining NHS staff?

While there have been numerous schemes in the NHS that have made use of premia over the last few decades, little is known about the impact and cost-effectiveness of these initiatives. These policies vary in complexity, scope and nature, as shown in Figure 4 below.

This lack of evaluation is true across the public sector; if anything, the scarce existing research casts more doubt over whether such pay supplements are effective (Brown and others, 2017). This is often demonstrated in the literature (albeit in North American settings) when looking at teacher bonus retention schemes, where studies have shown that salary supplements are often insufficient to incentivise teachers for other factors such as working in an area of high deprivation (Clotfelter and others, 2008).

It would be useful to know the extent to which financial incentives help solve NHS staff shortages in areas that historically struggle to recruit. This is particularly important given the ‘levelling up’ agenda, through which there is a likely expectation for the NHS to eliminate the unwarranted variation in staffing levels between areas (Hutchings, 2021). In evaluating the impact of a scheme, there are a number of different interim outcomes that we discuss below.

Firstly, we need to know whether premia schemes attract enough people. In some cases, we do know that – at the very least – people took up places which had premia attached. For example, Health Education England’s report encouraging fill rates for TERS (Health Education England, 2020). However, it is not always clear the extent to which funding changed behaviours, for instance, how many medical trainees would take up training posts in the absence of TERS. In Scotland, the influence of TERS was not as strong as other motivators, such as the location of family or a partner and pre-existing geographical preferences. This suggests that pay packages may not be a sufficient offer on their own (Lee and Cunningham, 2019). Indeed, London has the highest vacancy rates in NHS acute, community and mental health settings, despite offering supplementary payments (NHS Digital, 2021).

Secondly, it is important to understand whether premia help with staff retention in the long term. Over the last 20 years, several premia schemes have focussed on growing the GP workforce (Department of Health, 2002; 2005), with a particular focus on improving GP supply in more deprived areas. Research suggests that these policies may have had an impact in increasing GP numbers in the most deprived areas and reducing inequity of supply relative to need – although this is only indicative rather than definitively measuring the success of the schemes (Fisher and others, 2022). In some cases it is still too early to tell; for example, TERS and the New to Partnership payment are relatively new programmes.

Thirdly, there should be comprehensive understanding of the effects of using local payments on neighbouring areas and other staff groups. For instance, one (albeit old) study highlighted that the use of sign-on bonuses was associated with nurses feeling that financial incentives were unfairly distributed, and increased the likelihood of losing experienced staff (Mantler and others, 2006). It is particularly important for neighbouring trusts to regularly review their use of premia to lower the risk of inadvertent competition in a given area, prevent wage spiralling, and strike the right balance between pay and non-pay benefits. There is also a risk that focussing on the needs of one specific group of staff may unintentionally have a knock-on effect for other staff groups, whose membership organisations could make the case for their staff to also receive premia.

On top of this, there are historic differences in the characteristics of staff who do and do not receive premia. One example is the previous uptake of consultants receiving national Clinical Impact Awards, where black and minority ethnic were underrepresented in the pool of those applying to receive an award, as well as having lower success rates than their white counterparts (Advisory Committee on Clinical Excellence Awards, 2021). That said, there has been a consultation on broadening access to CIAs among the consultant workforce, including encouraging more applications from female staff, people of colour, and those working part-time (NHS Employers, 2022; Department of Health & Social Care, 2022). The process of offering other forms of premia to staff should also consider how fairly they are distributed with respect to the demographics of staff.

Are recruitment and retention premia worth it?

The limited evidence available presents arguments for and against the use of premia. Fundamentally, there needs to be some clarity from policymakers on the purpose and eligibility of such payments, including the high cost area supplement.

The situation is complex: there are multiple employment contracts for different NHS staff, which all have differing approaches to premia. On top of this, variation in attitudes to premia exist between trusts, which can create unhelpful competition between them. While one trust may advertise pay supplements to fill a post, another may offer existing staff promotions to higher bands. As NHS trusts increasingly have responsibility for some premia schemes, this is likely to create more ambiguity and inconsistency in the application and impact of premia, which will need careful monitoring and evaluation going forward.

As a starting point, for each scheme it would be helpful to know:

- whether they are attractive for prospective applicants

- whether they increase staff retention in a given area

- if the benefits of these schemes outweigh the cost

- what, if any, are the unintended consequences of premia on other areas, staff groups and characteristics.

Independent evaluations should be commissioned to understand their effectiveness. There also may be value in the government identifying and sharing best practice of the use of premia across different sectors, as well as drawing on examples from other UK nations.

There must also be further research to understand the motivations behind staff taking up these payments. It is also important to recognise non-financial incentives that are valued by NHS staff that could be used instead of, or in addition to, premia. This better understanding should help design the future mechanisms for recruitment and retention that the NHS so clearly needs.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Recruitment and retention premia schemes in the English NHS

Appendix 2: Number of staff receiving premia and estimated cost by staff group

Appendix 3: Areas eligible for the high cost area supplement for NHS Agenda for Change staff

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to those in the Department for Health & Social Care, NHS England and NHS Improvement, Health Education England and the BMA and the Health Services Management Centre who took the time to provide valuable insights for this project – in particular, we would like to thank Angie Walsh OBE, Dr Sharon Harrison and Professor Mark Exworthy for reviewing an early version of this briefing. Thanks also to David Gunner for helping us with our analysis of Market Forces Factor data, and to Professor Roger Seifert for his help with our recruitment and retention premia policy timeline. We would also like to thank our colleagues Sally Gainsbury, Helen Buckingham, Rowan Dennison and Eleanor Martin for providing feedback on a draft version.

Methodology

This project had three research components: a literature review, analysis of quantitative data and scoping interviews.

Literature review

We conducted a rapid literature review, developing search terms with the Health Services Management Centre, a specialist centre based at the University of Birmingham. We ran the terms across several academic and ‘grey’ literature databases, including the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts (ASSIA), Web of Science, and Scopus.

The literature review inclusion criteria required that the papers were in the English language only, and that they were either policy papers, ‘grey’ papers or academic papers. The initial search focussed on studies based in the UK only, but this was then broadened to include literature from other countries.

The search term was as follows:

[NHS OR healthcare OR health care OR health services] + [recruitment OR retention OR RRP] + [premia OR premium OR golden hello OR money OR budget OR finance] + [incentive OR salary supplement OR bonus]

We also conducted a manual search to identify wider literature not picked up by the search strategy.

Quantitative data analysis

We analysed data on NHS staff earnings estimates published by NHS Digital. We also reported the ranges of basic and supplementary pay as set out in the most recent employment contracts for NHS staff. We also used Trust Accounts Consolidation data as a means to estimate the cost of recruitment and retention supplements as a proportion of total spend on salaries and wages.

To calculate the effects of the staffing adjustment (in the market forces factor (MFF) formula) on funding allocations to NHS trusts, we moved the weightings attributed to staffing adjustments in the formula, with the weights reapplied in the ‘Other’ category, which created modified MFF values. We then calculated alternative operating income values for NHS trusts by dividing the original income values by the original MFF values, which was then multiplied by the modified MFF values. We then normalised the income values by multiplying each trust’s alternative income value by the sum of the total original operating income divided by the sum of the alternative operating income. To calculate the absolute differences in resource allocation, we subtracted the original operating income value from the normalised operating income value.

We used private rental market statistics from ONS as a crude measure of the cost of living.

We also used information on the number of Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme places for GPs to estimate the cost of the scheme per year, assuming that all places are filled and all postholders work full-time.

Scoping interviews

We spoke to stakeholders from NHS England and Health Education England in order to draw out additional insights about decisions to use premia and what they are intended to achieve.

References

ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON CLINICAL EXCELLENCE AWARDS 2021. 2020 ACCEA Annual Report. GOV.UK.

BELL, D., ELLIOTT, R. F., MA, A., SCOTT, A. & ROBERTS, E. 2007. The Pattern and Evolution of Geographical Wage Differentials in the Public and Private Sectors in Great Britain. The Manchester School, 75, 386-421.

BOLTON, P. 2021. Student Loan Statistics. House of Commons Library.

BROWN, D., REILLY, P. & RICKARD, C. 2017. Review of the Use and Effectiveness of Market Pay Supplements – Project Report. Institute for Employment Studies.

CLOTFELTER, C. T., GLENNIE, E. J., LADD, H. F. & VIGDOR, J. L. 2008. Teacher Bonuses and Teacher Retention in Low-Performing Schools: Evidence from the North Carolina $1,800 Teacher Bonus Program. Public Finance Review, 36, 63-87.

CRAWFORD, R., DISNEY, R. & EMMERSON, C. 2015. The short run elasticity of National Health Service nurses' labour supply in Great Britain. IFS Working Papers.

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 2002. NHS GP "Golden Hello" Scheme. In: DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (ed.).

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 2005. Framework for the primary care development scheme to replace the GP Golden Hello scheme. In: DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (ed.).

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 2012. NHS Pay Review Body - Market Facing Pay: Written Evidence from the Health Department for England – April 2012 In: DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (ed.). GOV.UK.

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & SOCIAL CARE 2022. Reforming the national Clinical Excellence Awards scheme In: DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & SOCIAL CARE(ed.). GOV.UK.

FISHER, R., ALLEN, L., MALHOTRA, A. M. & ALDERWICK, H. 2022. Tackling the inverse care law. The Health Foundation.

GAINSBURY, S. 2021. Checking the NHS’s reality: the true state of the health service’s finances. Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/checking-the-nhs-reality-the-true-state-of-the-health-services-finances [Accessed 21 December 2021].

HANSARD. 1986. Written Answers to Questions [Online]. UK Parliament. Available: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1986-12-17/debates/e3a3658c-1c23-4d33-818d-4a55b412a2f3/WrittenAnswers [Accessed 17 December 2021].

HEALTH ECONOMICS RESEARCH UNIT 2009. Distributing public funding to the NHS in England: taking account of differences in local labour market conditions on NHS recruitment and retention. University of Aberdeen.

HEALTH EDUCATION ENGLAND. 2020. Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme to support GP trainees [Online]. Health Education England. Available: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/news-blogs-events/news/targeted-enhanced-recruitment-scheme-support-gp-trainees [Accessed 21 December 2021].

HUTCHINGS, R. 2021. What might ‘levelling up’ mean for the NHS? Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/what-might-levelling-up-mean-for-the-nhs [Accessed 21 December 2021].

LAZOU, J. 2012. Independent Pay Review Body? Maybe next year. Mental Health Nursing (Online), 32, 19-20.

LEE, K. & CUNNINGHAM, D. E. 2019. General practice recruitment - a survey of awareness and influence of the Scottish Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme (TERS). Education for Primary Care, 30, 295-300.

MANTLER, J., ARMSTRONG-STASSEN, M., HORSBURGH, M. E. & CAMERON, S. J. 2006. Reactions of Hospital Staff Nurses to Recruitment Incentives. Western Journal of Nursing Research.

NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE 2013. Managing NHS hospital consultants. National Audit Office.

NHS DIGITAL 2021. NHS Vacancy Statistics England April 2015 – September 2021 Experimental Statistics. NHS Digital.

NHS EMPLOYERS 2021. NHS Terms and Conditions of Service Handbook. NHS Employers.

NHS EMPLOYERS 2022. Local clinical excellence awards 2021-2022: how to calculate the minimum funds for investment [Online]. Available: https://www.nhsemployers.org/publications/local-clinical-excellence-awards-2021-2022 [Accessed 12 May 2022].

NHS ENGLAND AND NHS IMPROVEMENT. 2018. NHS could free up £480m by limiting use of temporary staffing agencies [Online]. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2018/08/nhs-could-free-480m-limiting-use-temporary-staffing-agencies/ [Accessed 2 March 2022].

NHS ENGLAND AND NHS IMPROVEMENT 2021a. Consolidated NHS provider accounts 2019/20.

NHS ENGLAND AND NHS IMPROVEMENT 2021b. Consultation on 2021/22 National Tariff Payment System: A guide to the market forces factor. NHS England and NHS Improvement.

NHS PAY REVIEW BODY 2020. Thirty-Third Report 2020. GOV.UK.

NHS WORKFORCE ALLIANCE. 2021. Supporting the NHS to eliminate off-framework spend and helping build a sustainable workforce for the future [Online]. NHS Workforce Alliance. Available: https://workforcealliance.nhs.uk/supporting-the-nhs-off-framework/ [Accessed 24 January 2022].

ONS 2021. Inflation and price indices. ONS.

PROPPER, C., STOCKTON, I. & STOYE, G. 2021. Cost of living and the impact on nursing labour outcomes in NHS acute trusts. Institute for Fiscal Studies.

REVIEW BODY ON DOCTORS’ AND DENTISTS’ REMUNERATION 2007. Thirty-Sixth Report 2007. GOV.UK.

REVIEW BODY ON SENIOR SALARIES 2012. Report on Locality Pay for NHS Very Senior Managers 2012. GOV.UK.

REVIEW BODY ON SENIOR SALARIES 2021. Forty-Third Annual Report on Senior Salaries 2021. GOV.UK.

ROLEWICZ, L. 2021. Chart of the week: Which areas of England have the highest number of patients per GP? [Online]. Nuffield Trust. Available: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/chart-of-the-week-which-areas-of-england-have-the-highest-number-of-patients-per-gp [Accessed 21 December 2021].

THE OPEN UNIVERSITY 2019. The Open University: Breaking Barriers in Nursing 2019. The Open University.

VAUGHAN, L. 2019. Should we use pay incentives for shortage specialties? The evidence suggests it’s worth a try. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2019/04/30/louella-vaughan-should-we-use-pay-incentives-for-shortage-specialties-the-evidence-suggests-its-worth-a-try/.