Bed occupancy rates – the percentage of beds available in hospitals that are occupied by patients – are a clear marker of the additional pressures experienced by hospitals during winter. Rising occupancy rates are associated with worsening A&E performance. Over the winter months, hospitals usually increase the number of general and acute overnight beds, but this is normally matched by an increase in the percentage of beds occupied.

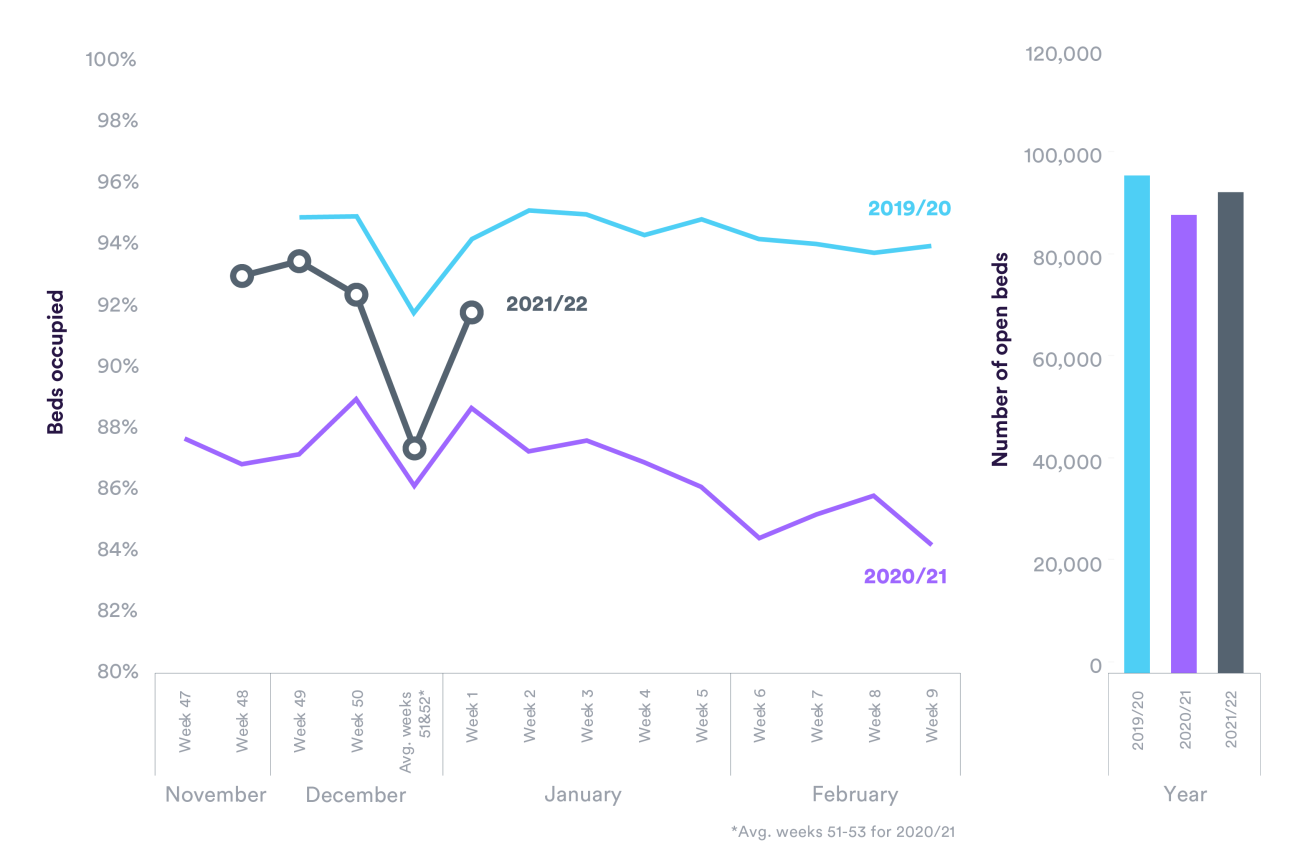

Bed occupancy rates this winter are currently lower than they were in the winters before the pandemic, although they are more similar to pre-pandemic years than to last winter. In the latest data, for the week ending 9 January, the weekly average bed occupancy rate in English hospitals was 92%, compared to 94% two winters ago. On the face of it, this would suggest that hospitals this winter are so far in a slightly better position than in pre-pandemic years. But is that really the case?

Last winter, despite soaring Covid-19 hospitalisations and a lower number of beds available compared to the year before, bed occupancy rates were consistently lower. This was down to less planned care being carried out and fewer A&E attendances. This winter, although so far there are fewer Covid-19 admissions, there hasn’t been the comfort of the lower A&E visits seen 12 months ago and there are more expectations on the amount of elective work carried out.

The pandemic also means that hospitals have been organised in new ways, such as separating out Covid-19 and non-Covid-19 patients, and putting in place other enhanced infection control measures like additional cleaning and using PPE. There is also the challenge of “incidental Covid”, where patients are hospitalised for non-Covid-19 related conditions but also have a Covid-19 infection. Along with the need to separate patients, this can complicate care and worsen existing conditions, which creates the potential for additional treatment requirements. All of this combined reduces capacity, both in terms of staff time and other resources. Hospitals will experience capacity pressures at lower overall occupancy rates than would previously have been the case.

Staff shortages have also been particularly bad so far this winter due to the high number of sickness and self-isolation absences since the spread of the Omicron variant, all at a time when staff are already burnt out and exhausted after nearly two years of grappling with Covid-19.

How all this combined will manifest itself this winter compared to last winter and winters before the pandemic is yet to be fully seen, but patient safety may be further put at risk and there will be more challenging weeks ahead for patients and staff.