Hospital readmissions – where patients return to hospital shortly following a first admission (30 days is the most widely used timeframe) – have been used as an indicator of hospital care quality for some years now.

If you took your car to be repaired, and it had to be returned to the garage a short time later, it’s probably because the mechanic didn’t do a good enough job the first time around. But in health care, it’s a lot more complicated than that and hospital readmissions are not always as straightforward as they seem.

As part of my studies at Radboud University (Nijmegen, the Netherlands), I looked at how readmission rates in English hospitals compared to those in my home country. In my analysis of the data available, I found rates to be higher in England than the Netherlands, especially for certain more vulnerable groups. So is there something England can learn from the Dutch system?

Findings

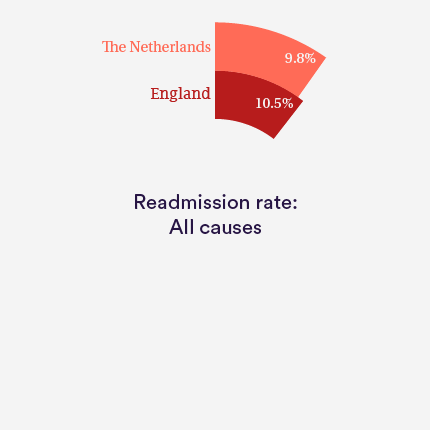

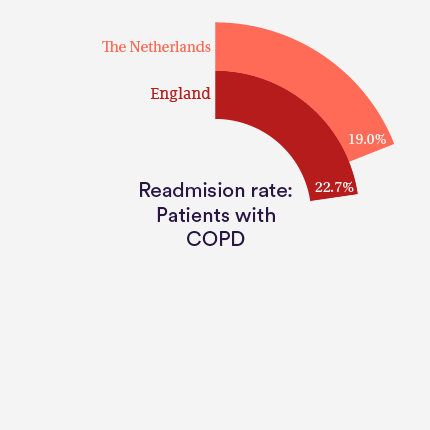

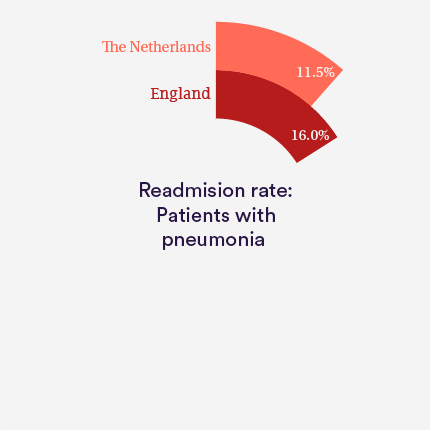

The all-cause readmission rate within 30 days of discharge in England is 10.5%, compared to 9.8% in the Netherlands. While this is a fairly modest gap overall, England has a higher readmission rate for certain patient groups, such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or pneumonia. Readmission rates for these patients are 22.7% and 16.0% in England, respectively, compared to 19.0% and 11.5% in the Netherlands.

Are emergency readmissions a reflection of quality of care?

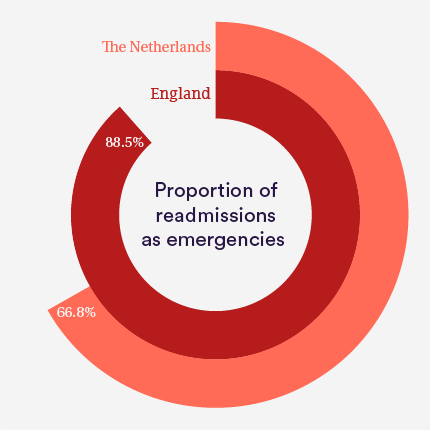

Of all readmissions within 30 days in England, 88.5% were people being readmitted as emergencies. In the Netherlands, the figure is 66.8%.

This could be a sign of poorer quality care in English hospitals, but there are other possible reasons. For instance, it could partly be explained by a difference in how each country organises its elective care. Accessibility of elective care (such as a scheduled hip replacement operation) continues to be a problem in the NHS as waiting lists are long, whereas the Netherlands has some of the lowest waiting times of all OECD countries. Because of this, the Netherlands has more planned readmissions, which may cause the relative proportion of emergency readmissions to decrease.

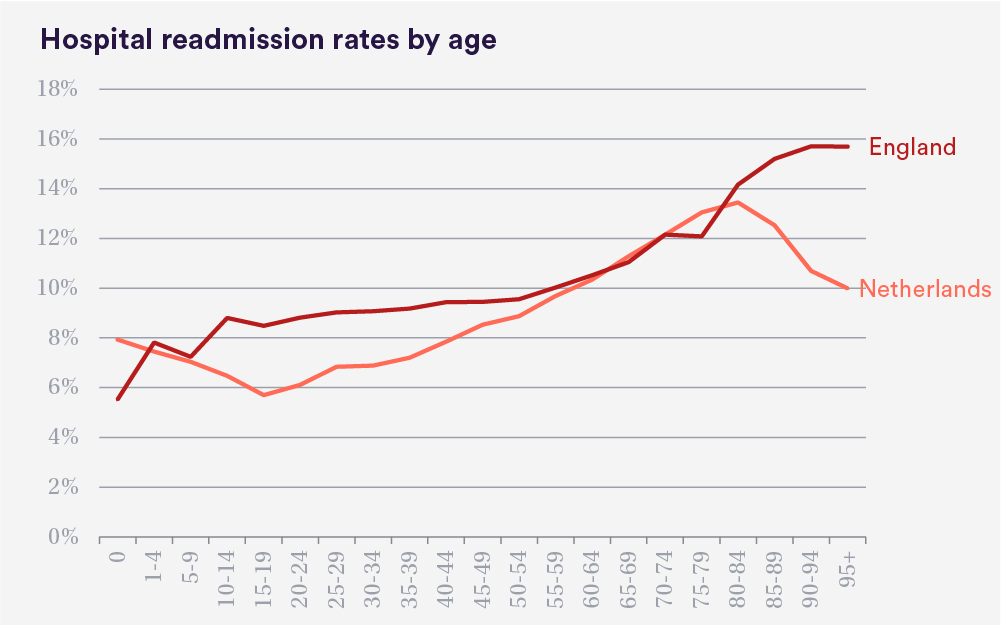

Are older people in England getting readmitted more often than they should?

The differences become especially striking when we look closely at readmission rates per age group. After the age of 80 years, readmission rates quickly go up in England, whereas in the Netherlands they drop.

These pronounced differences may be partly explained by differences in end-of-life care between the two countries. In the Netherlands, a third of all deaths occur in hospital, whereas in England the figure is well over half. And for the oldest old, the gap is even greater. Only one in six people aged 90 and over die in hospital in the Netherlands, compared to more than half in England.

Towards the end of their life, patients in England are therefore more likely to be readmitted to hospital. Since most people prefer to die at home, a target to decrease emergency readmissions in their final years may be appropriate.

Length of initial stay in hospital

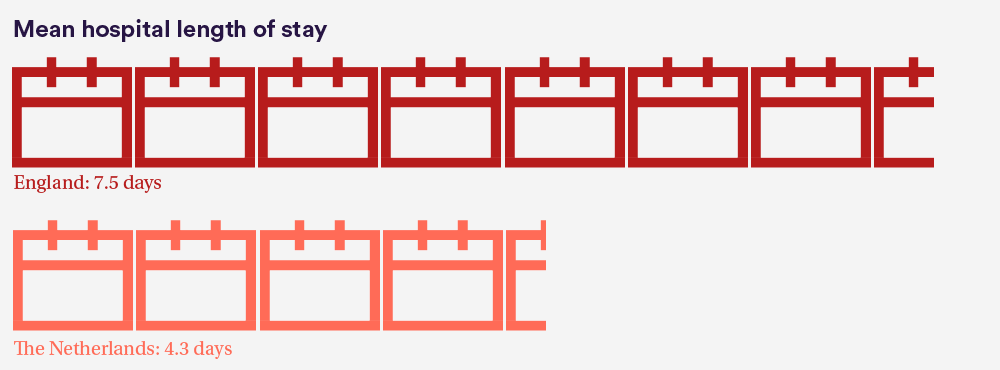

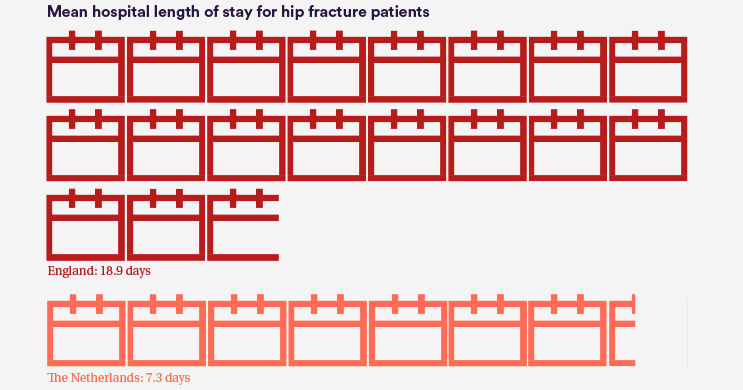

One possible hypothesis for the lower readmission rates could be that patients in the Netherlands are kept in hospital for longer during their initial stay, reducing the need for them to be readmitted. But the evidence does not support this.

In fact, the Netherlands has a shorter mean length of stay than England – 4.3 days versus 7.5 days, respectively. And this discrepancy becomes especially prominent for certain conditions. The mean length of stay for hip fracture patients in the Netherlands is only 7.3 days; in England, it is over double that (18.9 days).

Shorter hospital stays in the Netherlands may reflect differences in the organisation of social care and intermediate care facilities in the two countries. The Netherlands has good provision of intermediate care facilities where patients can recover after they have been discharged from hospital, or they receive care at home after discharge. In England, these facilities are less prevalent, resulting in people needing to recover in hospital if they are unable to be discharged home.

Conclusions

While readmission rates seem to be similar in the Netherlands and in England, it is telling that England has more emergency readmissions and a much higher readmission rate for elderly patients and those with certain types of conditions. Length of stay in England is also higher than in the Netherlands.

There are multiple factors that could explain why England performs worse than Netherlands on these measures.

Health spending should not be overlooked. Health expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product is higher for the Netherlands than for England – 12.9% versus 9.3% – which makes the Netherlands the most expensive health system in Europe and among the top 10 in the world. It is to be expected that paying less for health care may result in worse quality care in some cases.

Wider systemic problems in England, such as waiting times for elective care and shortages in community and social care, can all exacerbate issues with hospital discharge – contributing to hold-ups in bed availability and readmissions back into hospital.

However, it is also worth noting that readmissions and length of stay cannot provide a complete picture of quality. Overall quality of care must take into account a broader array of indicators.

The Dutch health care system

The Dutch health care system is different from England’s. Most importantly, the system in the Netherlands consists of a single compulsory insurance scheme with multiple private health insurers. Health insurers can negotiate to a certain extent with health care providers on price, volume and quality of care, and are allowed to make a profit and pay dividends to shareholders. The government has a role of “watchdog” that keeps an eye on progress rather than a direct steering role. Both the Netherlands and England have general practitioners whose core function is to act as gate-keepers.

Method

This study uses anonymised person-level Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data from the Health & Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC), and LBZ (Rural Basic Registration Hospital Care) data from Dutch data organisation DHD to compare the UK and Dutch health systems. We compared hospital-wide readmission rates from England and the Netherlands – specifically for the following diagnosis groups: hip fracture, acute myocardial infarction, coronary atherosclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, biliary tract disease, pneumonia and urinary tract infections. Readmissions were classified and compared between the countries.

Femke completed a research internship at the Nuffield Trust in July 2016, as part of her Bachelor in Biomedical Sciences at Radboud University (Nijmegen, the Netherlands).

Suggested citation

van der Bruge F (2017) 'Readmission rates: what can we learn from the Netherlands?' Nuffield Trust comment, 11 January 2017. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/readmission-rates-what-can-we-learn-from-the-netherlands