The current NHS pay disputes are increasingly looking like a lose-lose situation. While we can only speculate on how they might conclude, there is a real risk that the outcome is bad for staff, bad for patients, bad for NHS employers, and bad for government. So, with trust rapidly draining from the pay review process, we present what we believe are long-overdue and workable recommendations aimed at ensuring that the pay review decision-making process is fit for purpose.

These recommendations focus first on the timing of the whole process; that there are live arguments over an existing pay deal when a new one should come into effect in around two months is muddying an already murky negotiation. Thereafter, the recommendations focus on ensuring that the process is based on a good understanding of the effect of pay, affordability, and fairness. Given the questions being asked about the independence and competence of the pay review bodies, a final action focuses on the composition of the review bodies and their secretariat.

A quick recap

The role of the two NHS pay review bodies is to consider evidence submitted to them before making recommendations to the UK governments on pay increases for most NHS staff. The NHS Pay Review Body covers around 1.4 million staff, including nurses, allied health professionals, clinical support staff, administrative staff and managers, while the Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration covers a further quarter of a million. In recent years, the Scottish government has chosen not to use the NHS Pay Review Body and instead negotiated directly with unions and employers.

The recommendations are not always implemented in full. The Health Foundation highlighted that even before the pay restraint of the 2010s, around one in three NHS nurses’ pay recommendations made by the body between 1984 and 2007 were either delayed or implemented in a staged manner. There have also been further deviations from the recommendations with, for example, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (but not England) providing one-off payments to health care (as well as social care) staff during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Our eleven-point plan

Timing

1. The UK governments should publish the pay review body recommendations and their pay offers in advance of the start of the financial year. In England, the most recent pay deal was published 110 days after it should have taken effect, and just two days before parliament rose for summer recess. The pay deals in Wales and in Northern Ireland were confirmed later still. This year, the higher salary levels have been backdated but – given rising inflation – such delays can cause very real cost-of-living challenges for some staff.

2. Pay deals should typically have a force majeure clause whereby they are reviewed if economic or service conditions fall outside set parameters. In setting pay deals, the review bodies and governments have to forecast levels of, for example, vacancies, labour market conditions and costs of living. These predictions will never entirely match the reality, but in some cases they can be far off. The current four-year pay deal for junior doctors (at 2% per annum) was agreed in 2019, so before the pandemic and also when inflation was predicted to be running at around 2% per annum.

Having a process for reviewing pay deals if the landscape significantly changes will also support the use of longer-term pay offers, which have been suggested by others as a way to “free up space for creative, longer-term thinking on pay”.

Evidence base

3. The pay review bodies should be funded to conduct or commission independent, in-depth research on the effect of pay on domestic and international recruitment, retention and participation. The current evidence base on the effects of pay is generally poor. However, the existing data on overseas recruitment, domestic supply, numbers leaving, and levels of part-time working are, while not perfect, sufficient to support evaluations of the outcomes of changes in pay. Such analysis should also capture – through, for example, discrete choice experiments and observed trends and variation – the effect of pay compared to other factors that affect working conditions and gain a robust, qualitative understanding of the relationships. The outputs should be peer reviewed and published in a timely manner.

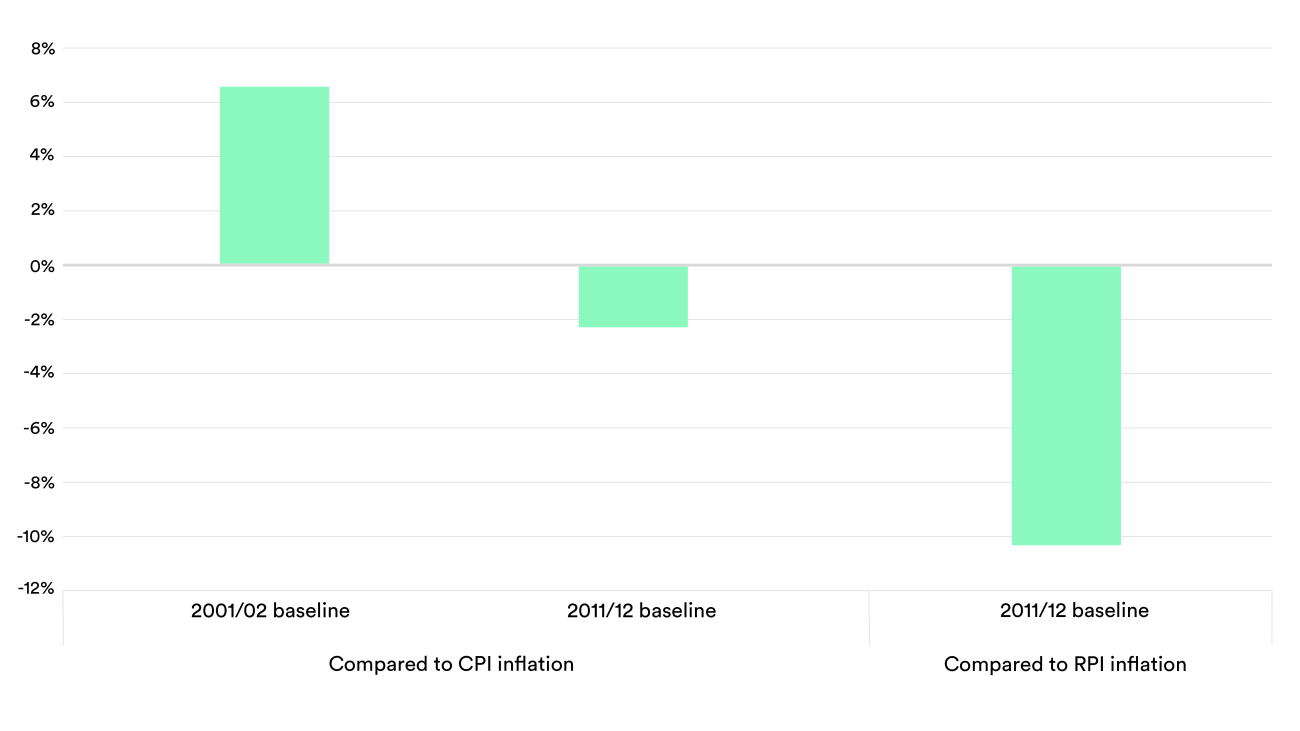

4. All parties – unions included – should commit to using appropriate measures of inflation and baseline years when calculating real-terms pay trends. In the current debate about pay, unions have often used Retail Price Index (RPI) as the measure of inflation, despite it not meeting the required standards for designation as a National Statistic and being widely considered to overstate inflation. RPI increased by 31% in the decade to 2021/22 compared to, for example, 20% for the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Similarly, all organisations need to be transparent about their choice of baseline. For example, to the last complete financial year (but before the recent spike in inflation), average nurse pay rose by 7% compared to two decades ago but fell by 2% over the last decade (see the chart below). That said, any historical comparisons need to recognise changes within professions with, for example, nursing now being graduate-only entry and these starters having greater levels of student debt. To support a shared understanding, the pay review bodies could publish various estimates of real-terms pay trends – along with other key resources – in advance of the call for evidence.

Affordability

5. Affordability should be considered in the context of the public purse rather than narrowly in terms of individual department budgets. Importantly, a significant proportion of any additional pay is returned to HM Treasury through income and other employment-related tax. On top of this, there are potential gains to the Exchequer through wider receipts from increased consumption and student loan repayments, as well as savings from potentially improved recruitment and retention. Given the public interest in having a fair pay settlement, siloed thinking around individual department budgets cannot be an excuse for not taking a balanced view on affordability to the public purse as a whole.

6. The pay review bodies should be explicit if any affordability envelope restricts them from recommending a pay deal which is sufficient to support a sustainable workforce that meets expected staffing and minimum service levels. Governments’ remit letters typically stress the importance that pay recommendations are affordable, while they separately also submit evidence on what their stated affordability limits are. Given this, the pay review bodies should state, as a minimum, which national workforce targets are most at risk given any constraints to the level of their pay deal imposed by the governments’ limits on the funding available.

Fairness

7. The governments’ remit for pay review bodies should explicitly cover the importance of fair pay between professions. An individual’s pay satisfaction is often determined by both its absolute and relative level. Given the move towards multi-disciplinary teams and changing skill mix, the review bodies should better consider the relative pay of different staff groups, particularly when covered by different contracts. Of note, only South Korea appear to have a higher pay difference between specialist doctors and nurses (3.7 times more) than England (3.3 times higher), with the average across the 26 countries with broadly comparable data being 2.3 times more.

Given that recommendations on the Agenda for Change contract cover over 20 times as many staff as recommendations for those on the consultant contract, there is a risk that affordability considerations are given more weight to the former, so biasing against their chances of higher pay increases.

8. The pay review bodies should take more explicit attention of the impact of the pay deals on pay inequalities between staff characteristics. Compared to nurses, consultants are three times more likely to be male but a third as likely to be Black or Black British. However, they received a more generous pay deal (4.5%, worth between £3,805 and £5,130) than nurses (4.3%, worth between £1,400 and £1,834). The review bodies’ remits include taking account of the legal obligations on the NHS, such as anti-discrimination legislation around protected characteristics such as race and disability. They have not, however, published assessments on how the effect of their recommendations vary between characteristics.

Pay distribution

9. The departments of health, employer representatives, pay review bodies and unions should conduct an in-depth but time-limited study on how the existing pay frameworks can be better used to allow greater and fair pay progression. Previous analysis has shown that graduates of nursing – as with creative arts and social care – typically see relatively small differences in median earnings between the ages of 30 and 40. The latest pay deal in England, Wales and Northern Ireland sought to retain some senior staff with a higher increase, but for many this is worth just an additional 43p a day.

Given higher average career earnings in medicine, for doctors the review body should revisit the relative levels of basic salary for new doctors (£29,384) to experienced consultants (£119,133), including the value of clinical excellence awards (up to £77,320). The influence of the NHS pension on recruitment and retention, including the balance between immediate pay versus contributions towards future earnings, should also be further explored.

10. The departments should urgently revisit the existing mechanisms for supplementing staff pay who live in areas of high cost. In England, around £986 million was spent on ‘London weighting’ in 2021, with these high-cost area supplements currently worth up to £7,377 a year for individual staff. However, such payments have not been comprehensively reviewed for nearly two decades. We previously noted that further work should be done to understand what the appropriate level of compensation would be for living and/or working in or around London, as well as in the other areas of the country that face the highest living costs. The changes in levels of remote working for some staff groups that precipitated from the pandemic makes this assessment even more necessary.

Governance

11. Governments – in collaboration with NHS employer representatives and unions – should review the current structure and resources of the pay review bodies. While there is potential value in independently produced pay recommendations, a review of the current arrangements appears to be well overdue. Such work should be informed by lessons from other, similar bodies, such as the Advisory Committee on Resource Allocations (the independent, expert advisory committee on how funding is distributed across the NHS).

The review should cover how the chair and members are appointed, the funding required to commission and conduct the needed research and evidence generation, and the expertise of the bodies and the secretariat which is provided by the Office of Manpower Economics. The review might also consider whether having separate pay review bodies, as currently the case, is still preferable.

Pulling it out of the fire

We have recently witnessed the first nurse strikes in England for nearly 50 years. While the current dispute largely centres on the actual pay deal rather than the mechanisms that surround it, moving forward NHS staff, patients and employers deserve a fit-for-purpose pay review process. This paper sets out some actionable recommendations – for the UK governments, pay review bodies and unions – intended to improve the current arrangements.

Such action should be taken urgently but must not stop there; indeed a recent systematic review found that increased pay alone was not sufficient to maintain staff retention and did not compensate for poor working conditions. Certainly, without being able to provide attractive roles for people to work in, the NHS will continue to spiral deeper into crisis.