The ‘devolution revolution’ is well under way, with 38 bids from groups of local authorities submitted to Whitehall for consideration under the Cities and Local Government Devolution Bill.

The Bill allows the Secretary of State to create devolution schemes for local authorities of all types, including counties. Successful areas will be granted devolved powers to address local economic development, transport, employment, housing, policing, and health and social care – depending on what regions have specifically asked for in their bids.

On the face of it, devolution has the potential to address the environmental, social and economic determinants of health, and has been welcomed in some quarters as a golden opportunity to improve population health.

However, it would be wise to try to take a balanced view here. Consideration of the practicalities reveals that, taken in isolation, the Bill alone may not provide workable solutions for local populations.

A real revolution?

Under the Bill, some of the most powerful tools to improve health would not be available to authorities, such as taxation on cigarettes and alcohol, regulation of limits on sugar and salt content in children’s foods. The power to change drink-driving limits would require more fundamental devolution of parliamentary powers, as was given to the Scottish Government under the 2012 Scotland Act. The same is true of commercial determinants like minimum unit pricing.

Furthermore, the Bill would not increase the legal powers of devolved areas to tackle environmental issues in addressing the public’s health over and above current legislative powers, which have enabled some areas to change the environment to improve health.

For example, there are already measures which can be used to limit planning applications for betting shops, place restrictions on alcohol licensing (such as a ban on irresponsible promotions), refuse planning applications for fast food outlets (achieved in Waltham Forest and Barking and Dagenham councils) and ban outdoor smoking (considered in Brighton).

In the rush to devolve power, it must not be forgotten that population measures to improve health are often more effective and cheaper than measures targeted at individuals. Some issues will be more appropriately and effectively addressed at a national level, rather than by individual devolved areas.

For example, the legislation banning smoking in workplaces and enclosed public places introduced across England in 2007 reduced bar workers’ exposure to second-hand smoke by 73-91 per cent and improved their respiratory health. In the year following the introduction of the legislation, the number of emergency hospital admissions for myocardial infarction (heart attacks) fell by 1,200 (2.4 per cent).

Perhaps, then, the Bill does not go far enough. Making powers available at a local level that complement national action on prevention could surely achieve significant benefits:

“To effect change local authorities may require the support of complementary national-level initiatives to make the most of their own strategies, powers and influence. House of Commons Review (2013).

The case in favour

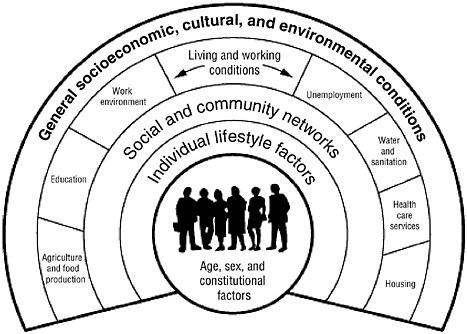

Yet the Cities and Devolution Bill has piqued the interest of those working in public health for good reason. The devolved powers promised – to be used in addressing local economy, transport, employment, housing, policing, and health and social care – are closely aligned with the determinants of health outcomes developed by Dahlgren and Whitehead on the ‘wider determinants of health’.

The Dahlgren-Whitehead model

Devolved areas will have the opportunity to tailor local solutions to local problems and use new powers to address these wider determinants and ultimately improve health and reduce inequalities. As the National Audit Office has described, addressing the wider determinants of health can change the lives people lead, the services people use and, ultimately, their health.

Furthermore, the devolution agreement in Greater Manchester is poised to obtain powers over the local economy, employment supports, housing and infrastructure that are only currently available to London, all of which are clearly intertwined with a social model of health. The Memorandum of Understanding between Greater Manchester partners, Public Health England and NHS England is impressive in its aims to focusing on preventative and targeted work to help the population stay healthy, be able to work and have better family life.

Indeed, Manchester offers a clear example of the potential for devolution to unite services to improve public health; those opportunities should be recognised more widely.

Interestingly, a Local Government Association review suggested that just 19 of the bids submitted for consideration under the Bill included a focus on health and wellbeing, which suggests that not all areas have made the connection to health as yet. This is the case despite the fact that the wider determinants of health are a key priority in the top tiers of local government, following the transfer of public health professionals, and a chunk of the public health budget and functions to local government.

The outlook

The momentum behind the devolution revolution has the potential to encounter pitfalls. There is a serious question to be answered over just how ‘local’ governance needs to be. The Bill’s proposed governance arrangements include “mergers of councils, moving to unitary structures or change the democratic representation of the area with different electoral cycles and fewer councillors”, which may result in greater distance being placed between local communities and decisions (exercisable at combined authority level).

Moreover, local regeneration does not come without its challenges - not least the gentrification of local areas or increased inequalities as a result of increased housing costs leading to a reduction in disposable income, and subsequent poor mental and physical health.

However, I’m an optimist, so I’m hopeful that the potential within the Bill to improve the health of local populations will be achieved. But it is unlikely that this alone will deliver the relationships needed to address the complexities of population health, along with the tools to achieve change.

Suggested citation

Davies A (2015) ‘Can the Devolution Bill revolutionise population health?’. Nuffield Trust comment, 20 November 2015. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/can-the-devolution-bill-revolutionise-population-health