The ambition to move care out of hospitals has been on the policy agenda for many years. Most recently, it has shaped the 44 Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) designed to transform local health systems across the country. NHS leaders and policy-makers alike hope that care in the community can stem rising levels of hospital activity (see chart below), while helping to save the NHS billions.

But while there is general consensus that care closer to home is often better for patients, doubts are beginning to emerge about the feasibility of these aspirations to save money. Just last week The King’s Fund warned that savings from STPs were not credible without extra investment to stabilise the NHS and social care.

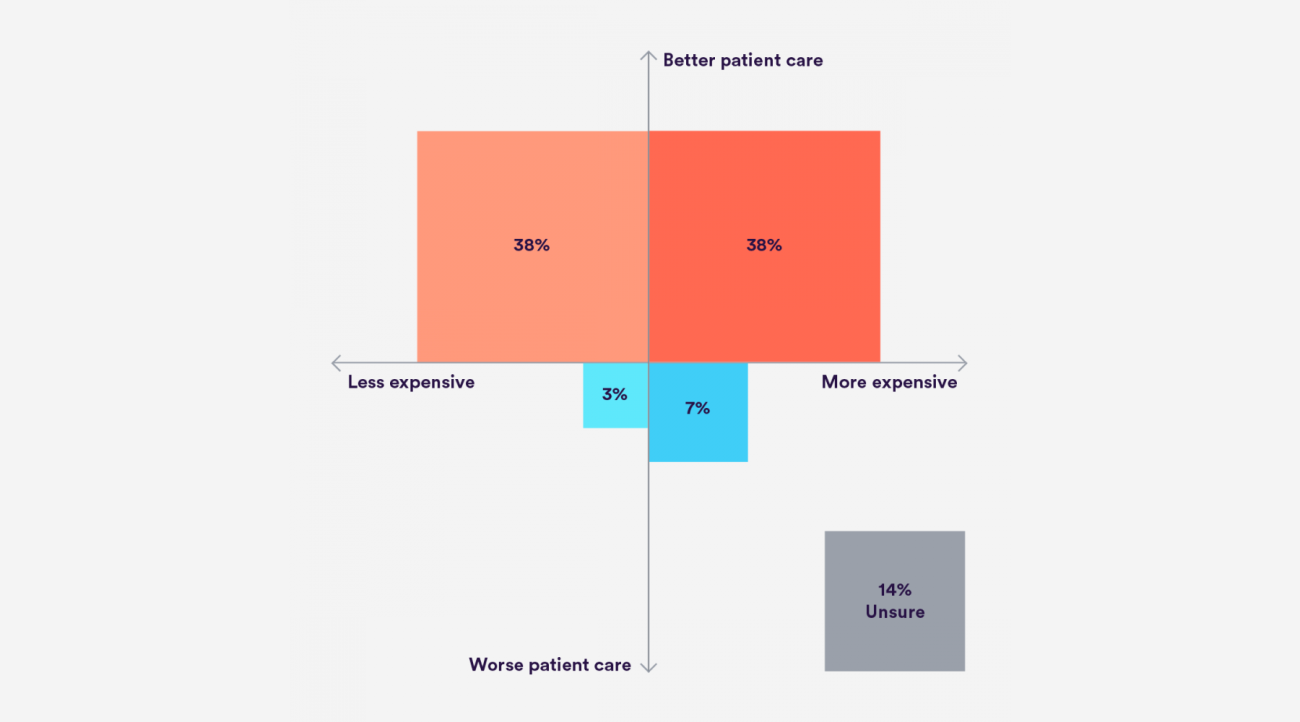

Our recent survey of 63 health leaders across hospitals, clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), local authorities and others encapsulates this dichotomy of optimism and doubt. While the respondents were almost unanimous in their belief that community intervention would improve patient care, when asked if it would save money, there were conflicting views. Around 40 percent believed it would, and the same number that it wouldn’t. A not insubstantial remainder didn’t know.

So what does the evidence tell us?

We reviewed the evidence around 27 schemes to reduce hospital activity, which we categorised into five areas: elective care; changes in urgent and emergency care pathways; avoiding hospital admission and accelerating discharge; managing ‘at risk’ populations; and supporting patients to care for themselves. We found that the health leaders were right: the vast majority of initiatives have the potential to improve patient experience, and in some cases outcomes.

For example, hospital at home – a scheme where patients are cared for in their own home, rather than in a hospital setting – has consistently resulted in improved levels of patient satisfaction compared to ordinary care. Care is structured around the patient and is provided by multi-disciplinary teams according to their needs.

Similarly, where patients are able to access specialist advice closer to home through, for example, consultant clinics in the community or GPs with Special Interests (GPwSI) patients tend to highly value the services.

Some initiatives have also improved outcomes. Remote monitoring, for example, where those with long-term conditions transmit their health information such as blood pressure or blood sugar levels to their healthcare team has resulted in reduced mortality for heart failure patients and improved glycaemic control for those with diabetes.

But the evidence is much less clear on cost – partly because robust economic evaluations are lacking in several areas. Nevertheless, we did find a minority of schemes can be cost –effective in the right circumstances. For example, where GPs can access specialist advice via e-mail or other means, a reduction in outpatient referrals and more timely access to treatment can make the service cost-effective. The majority of initiatives that have been the subject of an economic evaluation though, were cost neutral or actively increased costs. The reasons are varied and context specific, although there are a few cross-cutting factors. One such factor is that services delivered in a central location like a hospital usually have a lower per-unit cost than those in the community, which can play a big part in making them cost-effective.

Implementing change

Of course the way in which schemes are implemented also affects their overall impact. To get them right many are resource intensive or place unrealistic burden on other parts of the system. In particular, many of the schemes we reviewed require those in general practice to take on new responsibilities or to work in ways they are not used to. This is a big ask when general practice is already stretched to the limit.

If general practice is going to take on more, it will require more resource – not only for additional personnel but also for improved infrastructure, additional training and greater collaboration with specialist and community services. In some cases revised payment structures and incentives are also likely to be required to formally reflect the shift in responsibilities from secondary to primary care.

Similarly, social care desperately needs additional resource to make initiatives intended to accelerate hospital discharge feasible and effective. For the health leaders we surveyed, these were the primary obstacles to successfully transitioning care out of hospitals (see chart below).

So what does this mean?

Moving care out of hospitals can deliver holistic, patient-centred care closer to home, improving patient experience. But in most cases it is unlikely to deliver savings. In the context of growing activity, and an absence of additional resource to support transformation, the long standing ambition to shift the balance of care from hospital to community may still prove to be elusive.

Suggested citation

Castle-Clarke S (2017) 'Hitting home: the evidence on care in the community'. Nuffield Trust comment, 1 March 2017. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/hitting-home-the-evidence-on-care-in-the-community