2022 will mark a quarter of a century since voters in Wales chose to move powers over many public services from London to Cardiff. Health and social care have become the giants among these responsibilities, accounting for almost half of the devolved government’s budget, and seen by the public even before Covid-19 as by far the most important area for which Wales is responsible.

The Welsh government has exercised its powers to determine a distinct structure for the health service. At the same time it has faced emerging problems seen across the developed world, from rising costs, to an ageing population and a historic global pandemic, and tried to address the health and social issues specific to areas of Wales.

The BBC asked the Nuffield Trust to review a wide range of data to examine what this has meant for patients. In particular, they asked how waiting times, the issue of the moment across the United Kingdom, compared with other UK countries and with historic trends. Comparable data is in troublingly short supply across the UK health services, as we and the Institute for Government have consistently warned. However, we were able to examine headline waiting time figures as well as some data on the Welsh population, health resources available, and efficiency to put them into context.

Waiting times

All parts of the UK have struggled with waiting times over the past decade – missing their targets as financial constraints were followed by workforce shortages and Covid-19. In general, patients in Wales wait longer on average than their English counterparts.

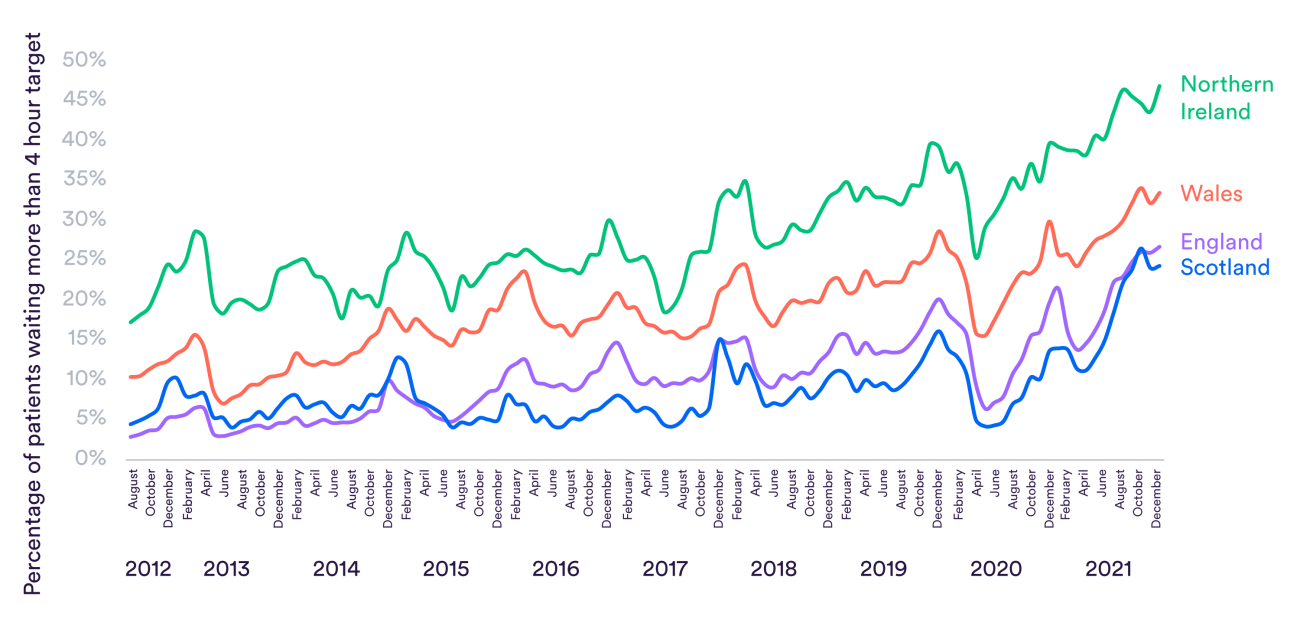

The graph below shows the proportion of patients who wait more than four hours in A&E departments before either being admitted to a ward, or being checked over and cleared to leave the hospital. Each country has a target that this should be less than 5%. The patterns are similar in each country, as they struggle with cold winters, the drop in attendance at the start of Covid-19 and then the return of patients as the pandemic ebbed.

Patients in Wales have been more likely than their Scottish or English counterparts to wait four hours in every single month since 2012 – though they fared better than those who turned to the struggling Northern Irish health care system. People waiting longer in A&E is often a sign that a health care system is struggling to free up enough bed space and staff inside the hospital to admit people.

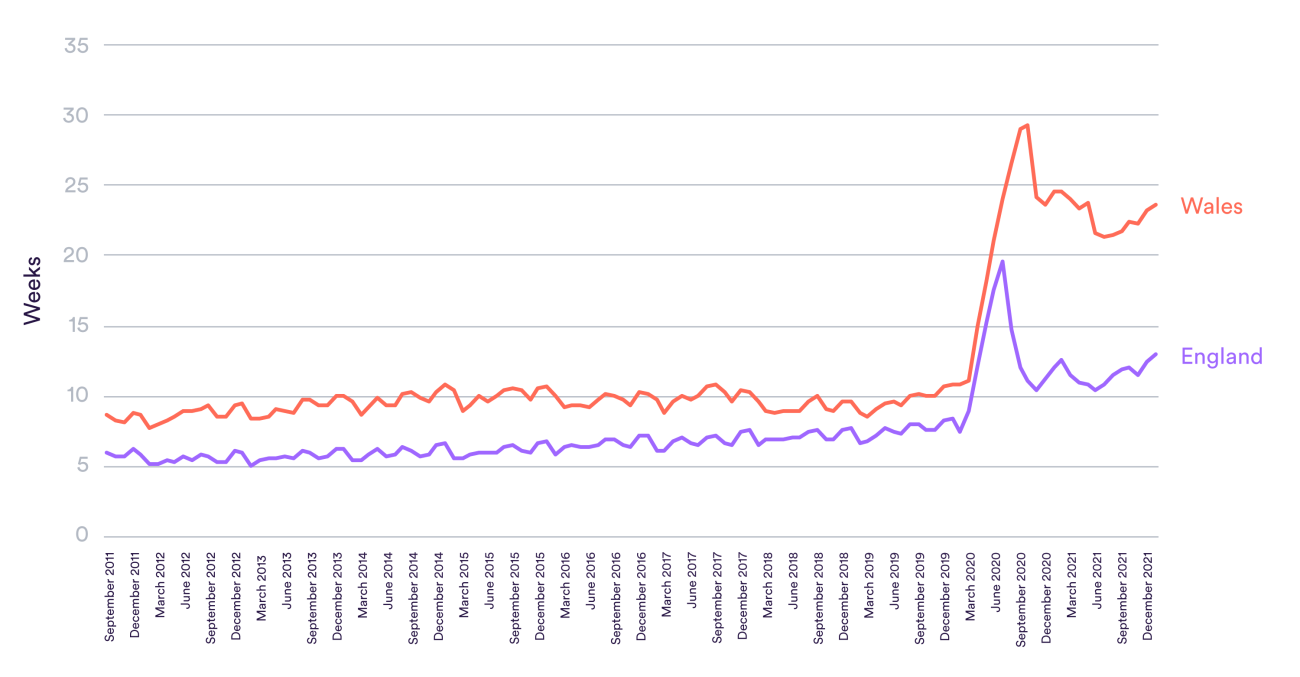

Each of the countries of the UK has different measures and targets for people waiting for planned care. The chart above shows one that can be compared between Wales and England – the median wait. This measures how long the person exactly in the middle of the queue has been waiting to receive treatment. Again, patients in Wales have consistently waited longer. The gap had been slightly closing before Covid-19, but median waits spiked further in Wales during the pandemic and did not recover as much.

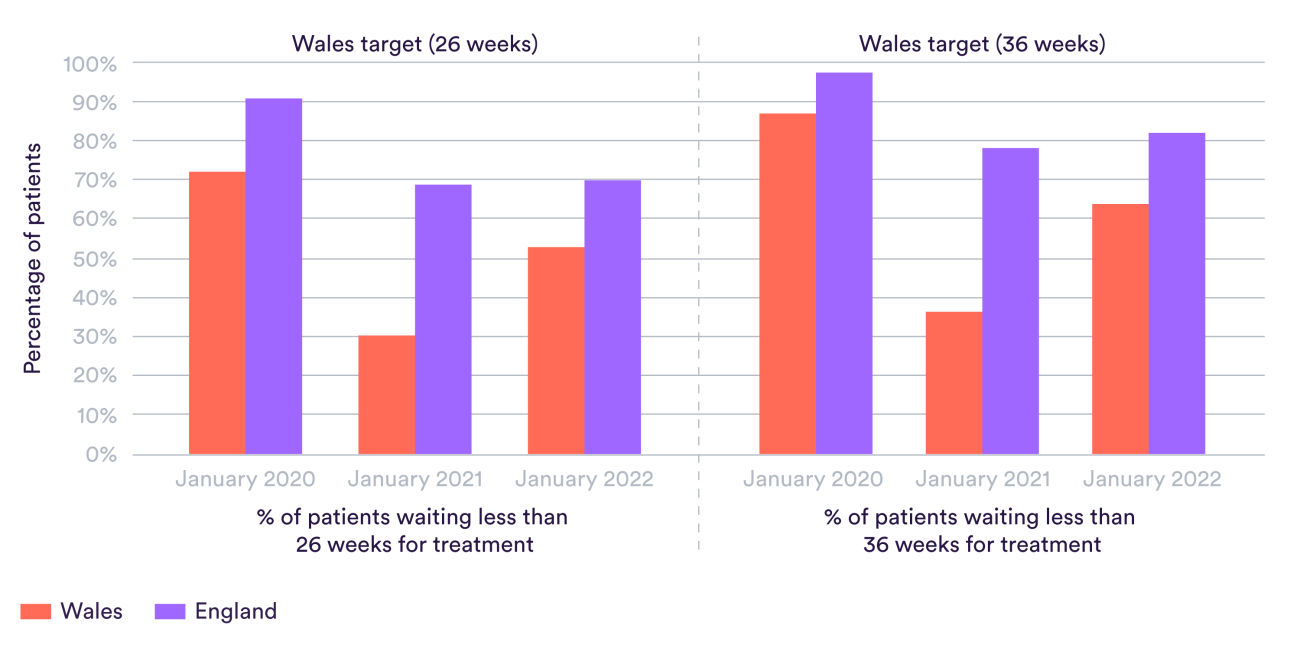

The same is true within key medical specialties as well. The chart below shows the proportions of patients waiting less than 26 weeks and less than 36 weeks for trauma and orthopaedics treatment. This would include, for example, hip and knee replacements. The same pattern of longer waits in Wales is visible. The gap is just as pronounced at the 36-week mark, which is perhaps surprising given that Wales, unlike England, has an explicit target that no patient should wait for 36 weeks.

Failing to meet waiting time targets for planned care could reflect a range of factors, including beds, staffing and productivity, what the health service’s priorities are, and how well it is coordinating diagnosis and outpatients.

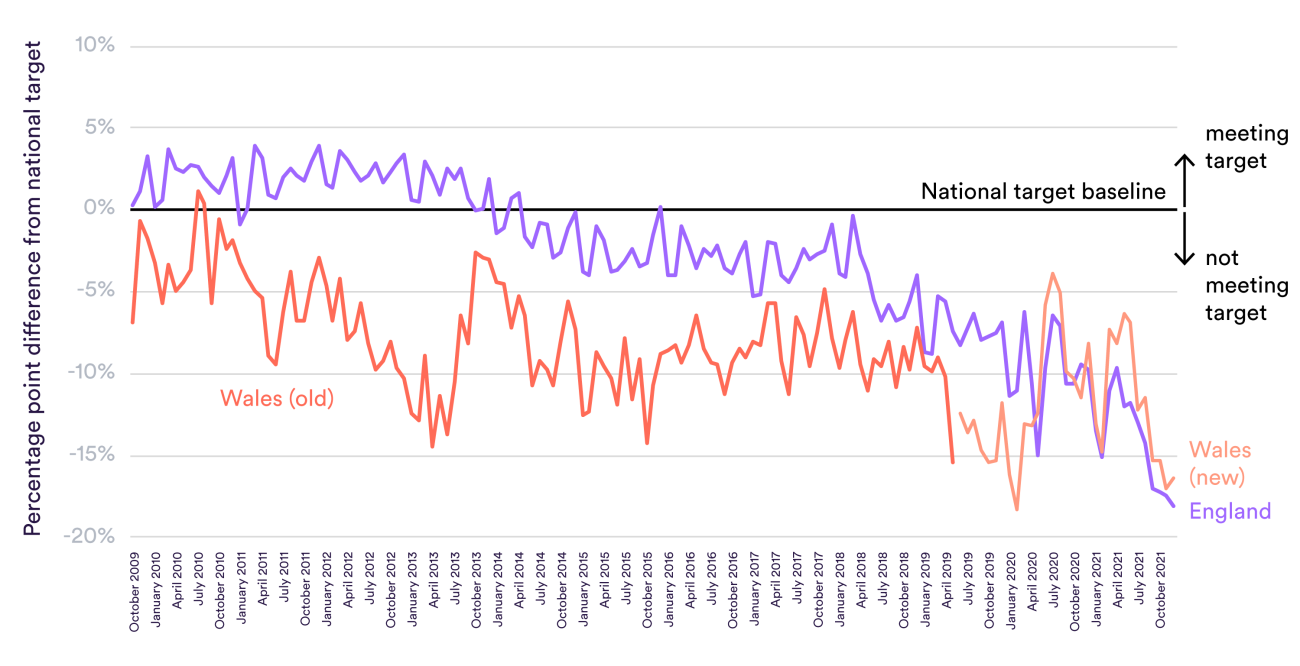

Not every area where patients have to wait for care shows such a clear difference. England and Wales have different cancer standards: the chart below shows how the proportions of patients starting treatment within 62 days stack up against their relevant targets.

Both countries used to apply these targets to patients referred in a particular category of urgency by a GP. During this period, both missed their target – the Welsh target was higher – but neither particularly fell behind the other. Since 2019 the Welsh NHS now counts all patients who wait from the point of cancer being suspected, whether by a GP, in A&E or during some other treatment. It has reduced its target from 95% to 75% to reflect this wider category. It has continued to miss this target by about the same as England misses its target: there is little sign here of Covid-19 being a greater problem west of the border.

The final outcome

Waiting times are an important measure of whether patients can really access the comprehensive health care the NHS promises. But saving lives and preserving health are the ultimate goal of a health care system.

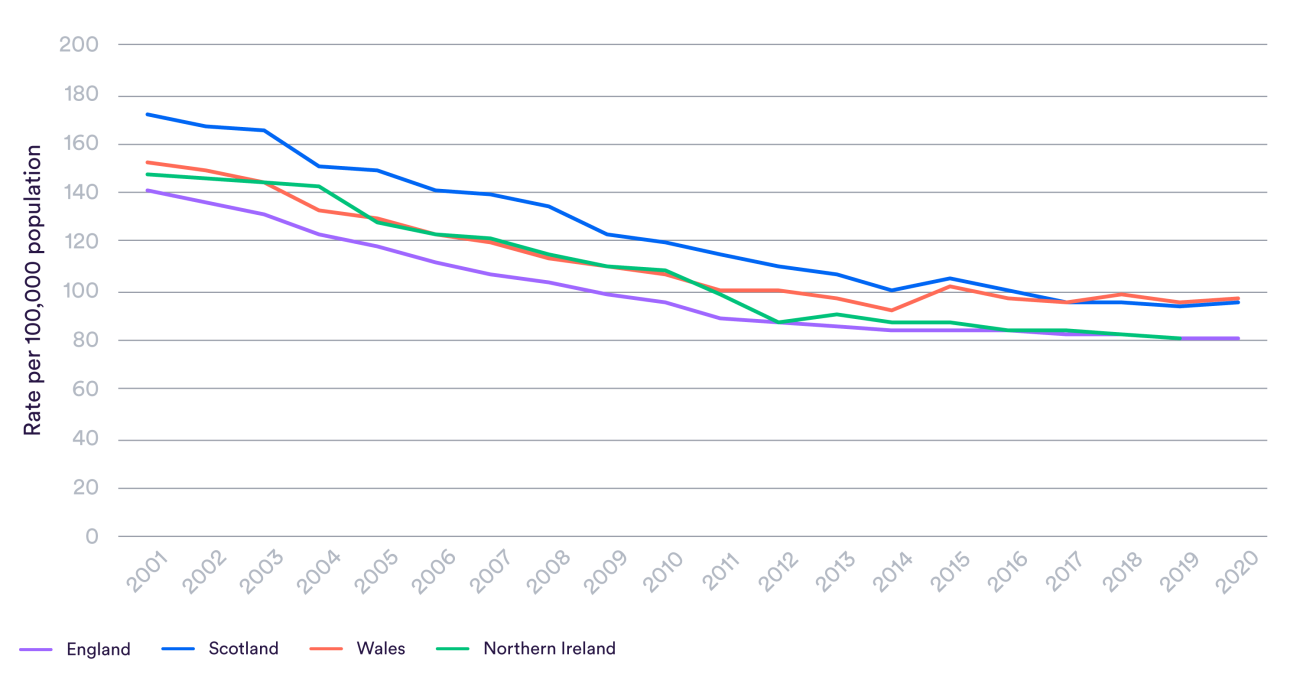

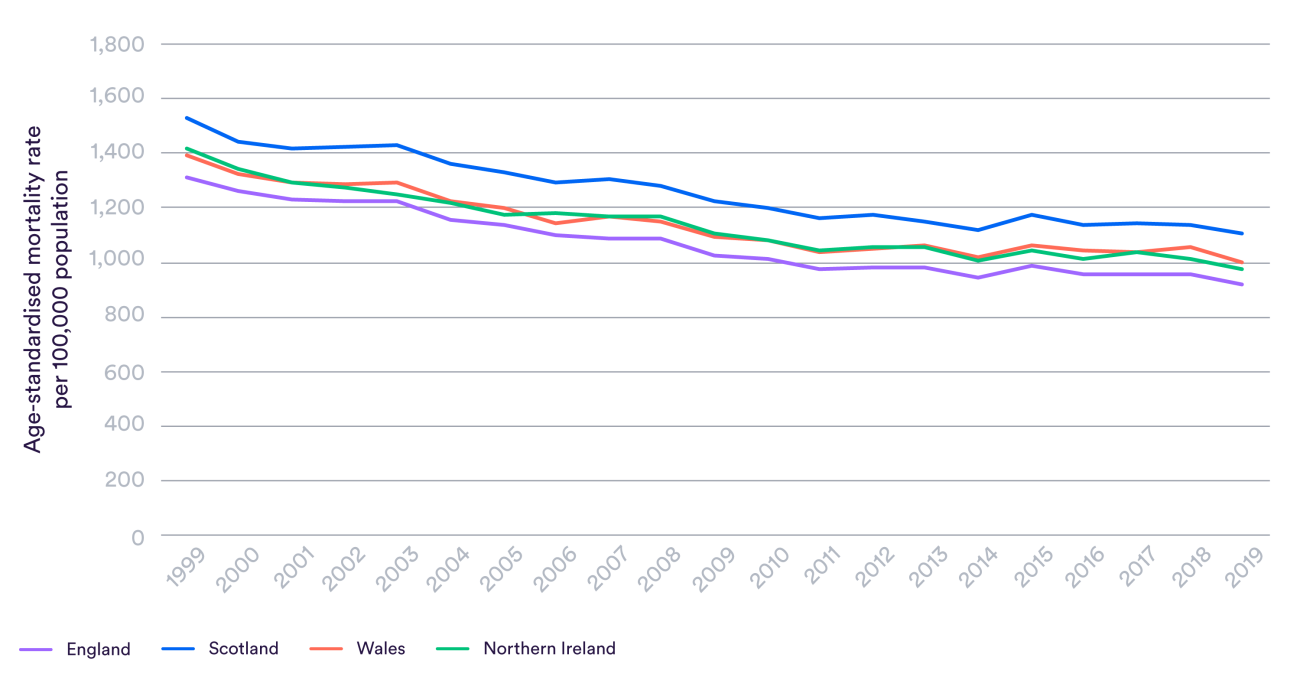

A full comparison of clinical outcomes between Wales and other UK countries would take months or even years and is beyond the scope of our work. We did, however, look at data the Office for National Statistics produces on treatable mortality – the rate at which people in each country die from causes which can be mainly avoided by timely and effective health care. These include, for example, breast cancer among women and epilepsy. The graph below shows this data adjusted for the different age structures of the UK countries.

While it has made progress since devolution, Wales currently has a higher rate of treatable mortality than England or Northern Ireland, and around the same as Scotland. Improvements have stalled in all four countries in recent years, but this slowdown seemed to happen earlier in Wales and there has been little progress for the last decade.

A more difficult task?

A number of factors might explain why the NHS in Wales seems to struggle to provide care quickly enough to meet its targets. One possibility might be that the population is less healthy and needs more treatment: people simply join the queue in greater numbers. This could help explain differences in treatable mortality too: perhaps the Welsh NHS is equally likely to save lives for these conditions, but they simply occur at a higher rate to start with.

There is some evidence supporting this. A person in Wales is more likely to die each year than a person of the same age in England. Studies have shown that how close people are to the end of their life is a powerful driver of how much health care treatment and spending they require.

Looking at other indicators that reflect the need to health care, we see a mixed picture. Wales has the oldest population in the UK, with 21.1% of people above the age of 65 compared to 18.6% across the UK. However, a lower proportion of adults drink alcohol compared to England and Scotland and, while 25% of people in Wales were obese in 2019, this figure was 29% in Scotland and 28% in England.

Inputs and outputs

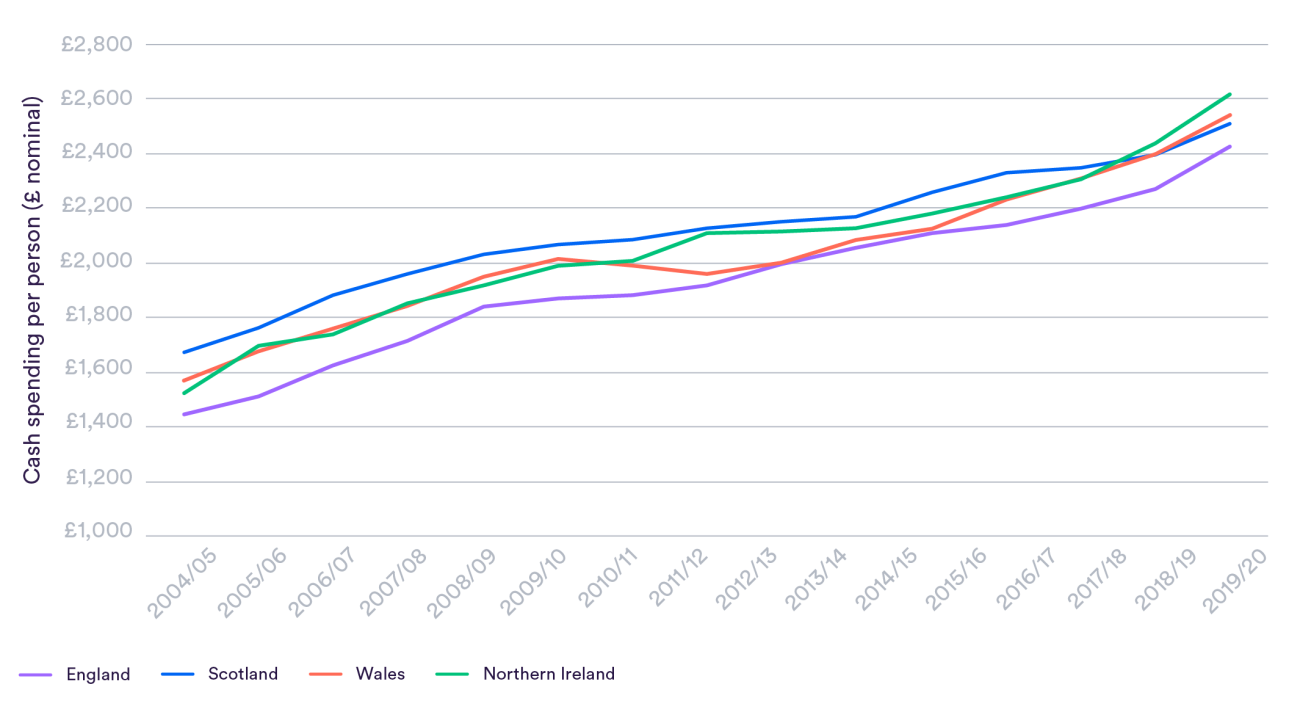

An important question is whether the Welsh health care system has an appropriately higher level of resources to meet the population’s needs. The money available to the Welsh government to fund the Welsh NHS, alongside its other responsibilities, is mostly distributed by the Barnett formula. This allocates changes in spending from Westminster roughly in proportion to the population of the different countries.

Because it largely rolls over historic spending, it can create fairly arbitrary outcomes, and in 2016 adjustments were made over a fear that Wales was missing out. Wales gets far more funding per person than England – around 15% more, or £1,325 per person more in 2019/20 – but less than Scotland or Northern Ireland.

However, Wales actually spent around 5% more than England in the year immediately before Covid-19. This smaller difference is because the Welsh government has prioritised health care slightly less aggressively and spends more on other services – including social care, where spending is 30% higher than in England.

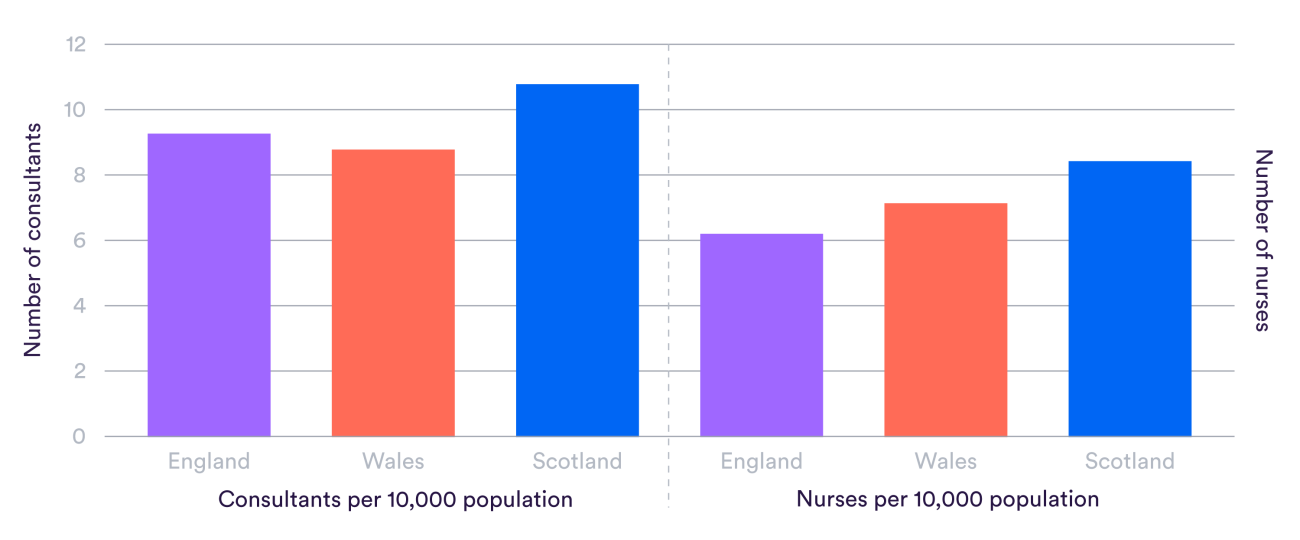

Looking at the numbers of staff, Scotland has by far the highest number of doctors and nurses, as shown in the figure below. Compared to England, Wales has fewer consultant doctors relative to its population size, but more nurses.

There are of course many other groups of staff vital to providing health care and countries may use different mixes of them, so interpreting differences in specific groups is difficult. However, consultants and nurses are certainly central to delivering care in all countries.

Looking over time, Wales has not grown the number of senior doctors as fast as England since 2009. This equates to around 260 fewer consultants in Wales. However, in the larger “scientific, therapeutic and technical” group containing staff such as physiotherapists and radiographers, Wales has grown its workforce faster, equivalent to around 370 more of these qualified professionals.

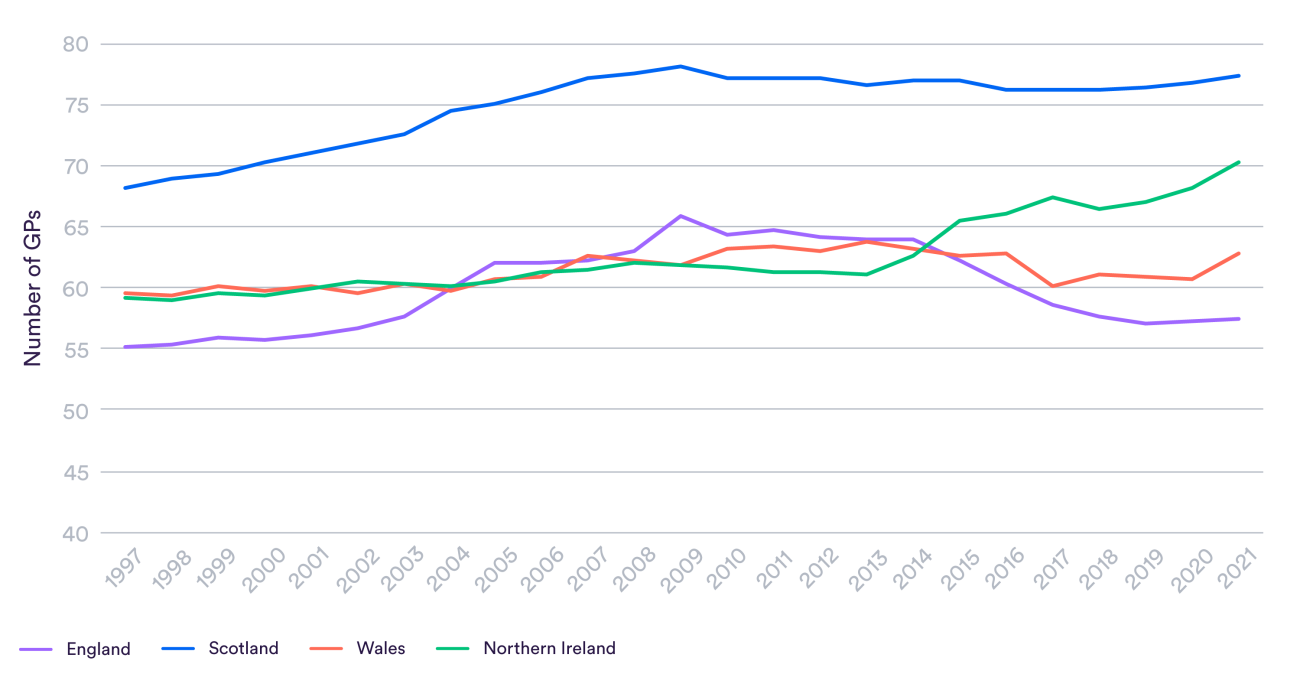

The number of GPs in Wales is broadly the same as a decade ago relative to the size of the population. Meanwhile, this ratio rose sharply in Northern Ireland but fell in England. The total number of GPs per person in Wales (63 per 100,000) is considerably lower than in Scotland (77) but higher than in England (57). These differences are equivalent to Wales having 170 more GPs than if they had English staffing levels, but 470 fewer than Scotland.

Wales has considerably more hospital beds than England relative to the size of its population. The latest figures from 2020/21 show that the Welsh health service had around 270 general hospital beds, not including maternity, mental illness or learning disabilities, for each 100,000 people. This compares to 170 in England.

In short, the Welsh NHS is generally somewhat better resourced than its English counterpart – though the difference is not consistently large. Does this mean it is really better equipped to meet patient needs, or worse, given its higher levels of need?

Several studies have tried to answer this for funding at least by applying the formula used within England and Scotland to decide how much money areas of the country receive. This essentially tells us whether the Welsh NHS is getting more or less money than it would if it was looking after the same population within England or Scotland. The University of Stirling found in 2013 that Wales had needs around 10% higher under both the Scottish and English formulas, and 16% higher with an adjustment for health inequalities. It actually spent around 2% more at the time, which has now risen to 5% more.

An efficiency gap?

Another possible explanation for patients waiting longer in Wales may be that the service is less efficient. Directly measuring this is difficult, but one significant measure is the length of time people stay in hospital. As long as good care is being provided, a shorter length of stay will usually reflect greater efficiency – more use of the latest medical techniques to treat people quickly, and a better organised system to get them safely discharged with the right follow-up care.

The average length of stay in Wales is much higher than in England, at seven days against 4.3 in 2020/21. This is a very large difference: patients in Wales are kept in hospital more than one and a half times as long on average. The difference actually grew in the three years before Covid-19 as England improved.

It might be that some proportion of this difference reflects patients being more unwell, or needing different kinds of treatments, but there are some serious questions to ask here. Northern Ireland and Scotland, which also have higher need and a more rural population than England, have somewhat higher length of stay but to a much lesser extent than Wales.

It is also possible that longer length of stay may have some benefits, reducing the chance that people are sent home too early only to have to be admitted all over again. Data from one clinical audit on breathing difficulties did find that this happened less in Wales.

Where we are able to look at this, it does not seem that the Welsh health service is spending more on what it purchases. Salaries are similar to England – slightly lower in the case of GPs who own practices. The cost to the health system of purchasing drugs, measured by the ‘net ingredient cost’ per prescription item, is lower in Wales.

Conclusion

It is clear that patients in Wales generally wait longer for care than their English counterparts. Looking at basic data for context suggests two possible causes.

Firstly, although the Welsh NHS receives more money than the English NHS per patient, this may not be enough more to account for an older population with a higher mortality rate.

It should be noted that total public spending in Wales – around 15% higher – is more in line with estimates of higher NHS need. The Welsh government has simply chosen not to focus its budget on health to the same extent as governments in London, who over the past decade have increased English NHS funding while cutting other budgets. These are not easy choices to make. This period in England has seen a dire situation emerge in social care, something it was outside the remit of this short project to compare.

A second reason may be that the NHS in Wales is less efficient or less focused on delivering timely care. While it may be influenced by the kinds of procedures people need, length of stay data appears to suggest that Wales is taking much longer to get patients treated and safely discharged. This may explain why it struggles to admit patients as quickly despite having many more beds. The OECD, in a review six years ago, warned that Welsh health boards lacked the capacity to drive improvement and innovation, and that central government needed to do more to support them and hold them to account.

There are very difficult years ahead for the NHS in Wales. Like its counterparts across the UK and Europe, it has seen burnout and delays from Covid-19 worsen what were already chronic problems with staffing and waiting times. But this should not stop difficult questions from being raised.

*Data analysis for this research was carried out by Sophie Flinders, Sarah Scobie, Billy Palmer, Jessica Morris, John Appleby and Liz Fisher.