Since clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) moved into the driving seat of the commissioning system 12 months ago, the breadth of the job they are expected to do has become apparent.

Responsibility for each of the big changes we are increasingly told that the NHS needs – better joint working with social care, further efficiency savings in hospitals, and radical change in the scale and scope of general practice – rests largely on the shoulders of CCG leaders as the key drivers of change.

It is the last point – the involvement of CCGs in primary care development – that was a particularly contentious issue in the run up to April 2013. With responsibility fragmented across a new system, formidable obstacles stood in the way of the new groups coming forward as leaders among their GP colleagues.

You don’t need to be a cynic to suspect that further reorganisation looms for general practice

Spectators wondered if NHS England would become the natural driver for improvement, given that they hold the contracts for GPs. And if CCGs tried to do so, would that lead to fractious relations locally, with GPs resenting colleagues bossing them about from their new pedestals?

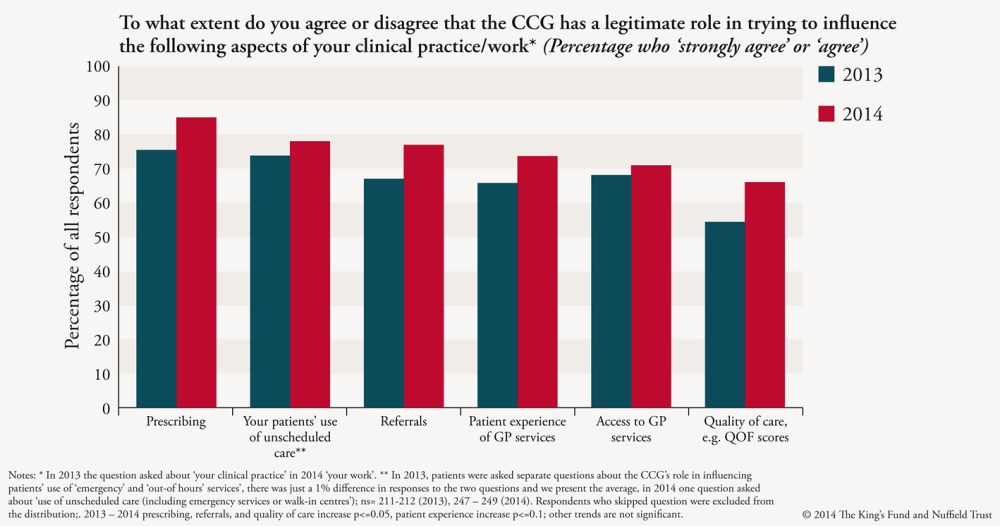

The answer to both questions appears to be no. GPs who took part in a survey conducted as part of an on-going three-year study being conducted by the Nuffield Trust and The King’s Fund, were more likely now to agree to the involvement of the CCG in their day-to-day practice than this time last year.

Before they were formally authorised to take over, CCG leaders told us that they were anxious about being seen to ‘police’ their colleagues and the perceived conflicts of interest that could result in them designing new services for primary care.

However, it seems that the past year has either served to calm anxieties about this type of relationship with CCGs, or simply that the policy direction has been accepted by CCG leaders and GPs alike (although these anxieties could resurface if CCGs take on a more formal role in aspects of GP contract management).

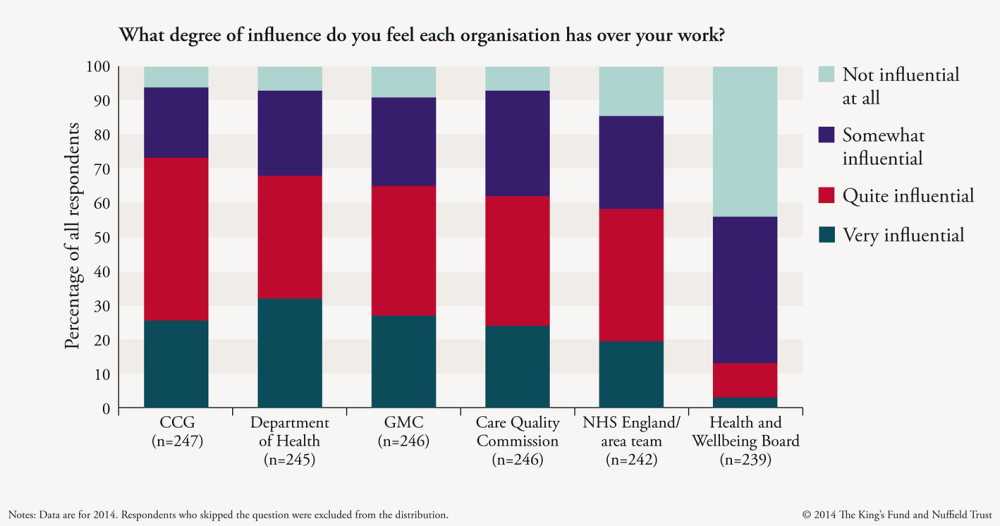

Interestingly, this could be linked to the fact that GPs feel that CCGs are the organisation that exerts the greatest influence over their work. This is a striking finding for several reasons. GPs are paid under contract from NHS England, and work in a system which still appears to support a powerful role for the Department of Health at the centre.

By contrast, although they do have a duty to support the development of primary care services, the core job of CCGs is commissioning care in hospitals, mental health units and the community.

Yet all the CCGs in our study are becoming more involved in the planning and development of primary care as the new system beds in. They are analysing and sharing performance data to see and explain how well their members are doing; visiting struggling practices in person; and designing financial incentive schemes.

All of our case studies are investing in interventions to bring extra capacity into primary care, interventions which necessitate complicated governance and procurement processes.

This survey also showed, though, that NHS England and its area teams have made their presence felt locally – with the vague uncertainty we found about their role last year diminishing. We talked in our previous report about a ‘carrot and stick’ relationship between NHS England area teams and CCGs. CCGs tended to give out the carrots, helping and supporting their colleagues to make improvements.

NHS England’s area teams, meanwhile, were more likely to wield the stick – enforcing contracts and carefully managing the performance of general practices.

Interviews with our case study CCGs suggest that in most places, the division of roles between CCGs and local area teams appears clearer than this time last year. Elsewhere, though, area teams may try to work more directly with practices, muddying the water where NHS England priorities and indicators are at odds with those of the commissioning groups.

As with much of the new structure of the NHS and other new local health and social care organisations, how well CCGs and area teams do in improving general practice seems to depend on the one element that can’t be designed or reorganised by policy-makers – historical and enduring relationships between individual managers and clinicians at a local level.

You don’t need to be a cynic to suspect that further reorganisation looms for general practice. Already, influential voices are asking whether the contracting and oversight job now done by area teams should be partly handed over to CCGs; or fully handed over to them; or given to Health and Wellbeing Boards. Politicians should be careful not to lose the progress that has been made over the past year.

Suggested citation

Holder H (2014) ‘Influencing GPs and the expanding role of Clinical Commissioning Groups’. Nuffield Trust comment, 1 April 2014. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/influencing-gps-and-the-expanding-role-of-clinical-commissioning-groups