With schools and sixth-form colleges up and down the country reopening after the summer holidays, the impact on children and young people’s mental health of the pressure they feel to do well in their education is a growing concern. Earlier this year, the NSPCC said that the number of referrals by schools in England seeking mental health treatment for pupils has risen by more than a third over the last three years.

The research that I and other academics have published today in Psychological Medicine looks further, and analyses mental health and wellbeing trends among children and young people over the past two decades. We looked at data from 140,830 participants aged between 4 and 24, across 36 national surveys in England, Scotland and Wales.

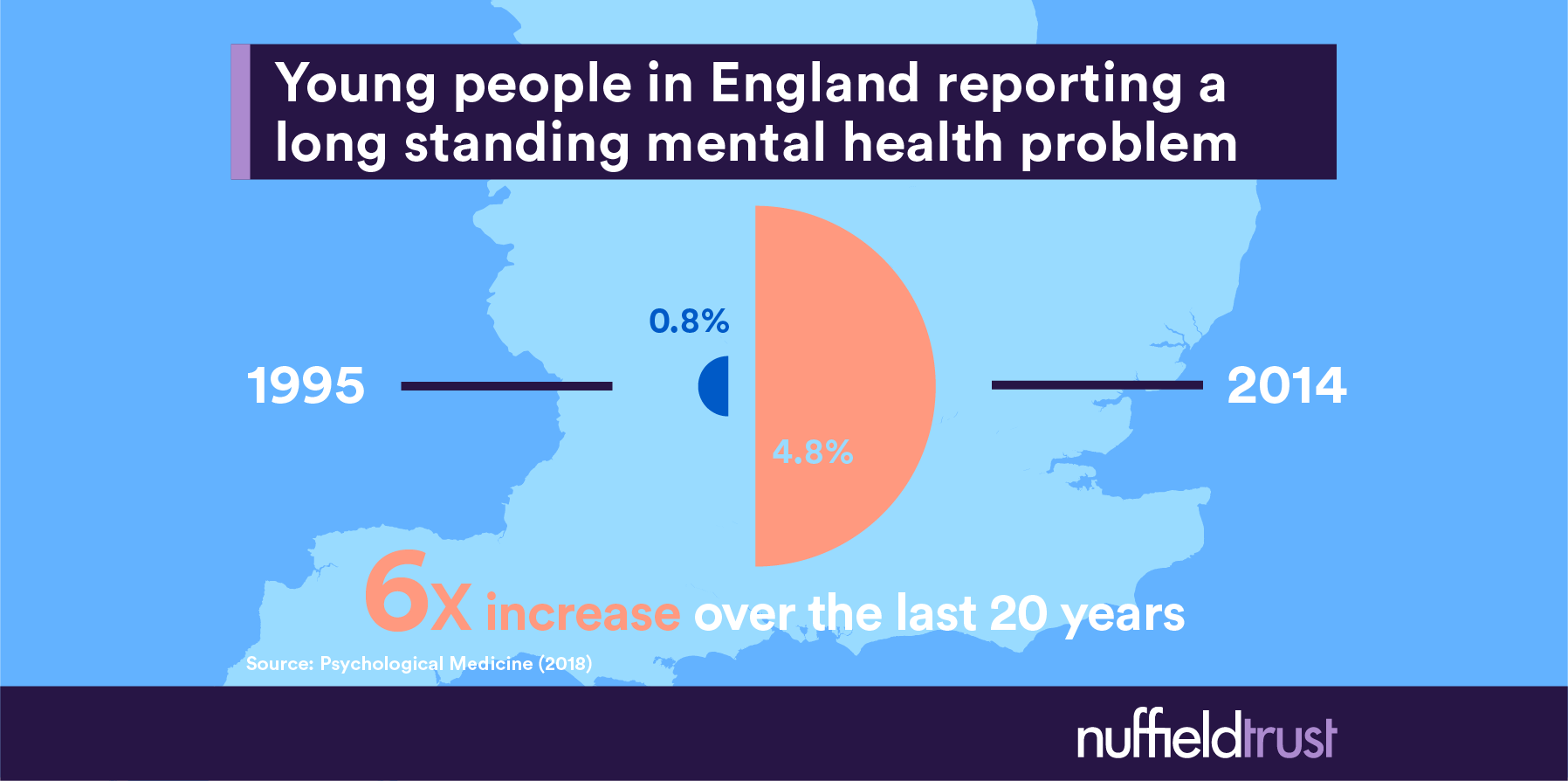

We found a striking, six-fold increase in how many children and young people in England reported having a long-standing mental health condition between 1995 and 2014 (from 0.8% to 4.8%). And among young adults between 16 and 24, there was an even larger, 10-fold increase – from 0.6% to just under 6%.

We found no consistent change in emotional and behaviour difficulties over most of that time, but did find early signs of increasing mental health symptoms and reduced wellbeing among young adults in more recent years (from 2011 onwards).

What’s behind the rise?

So how can we explain all this, and what are the implications for policy-makers and those planning mental health services?

Well it’s likely that one of the main reasons for the increase in reported mental health conditions is greater awareness and less stigma and reluctance when it comes to talking about mental health problems. In many ways, this is a good thing. We know that around three-quarters of lifelong mental health problems start before the age of 24 – a greater willingness to discuss these problems and seek help can reduce their severity and long-term impact.

While treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy and family therapy are effective, sadly we know that in many cases, child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) are too stretched to meet the increased demand, which is resulting in referrals being declined and long waits for many young people who are seen.

As well as greater awareness, other evidence point towards a likely increase in anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions among young people, at least since around 2011. There has been an increase in hospital admissions due to teenage girls self-harming, a rise in teenage suicides and more demand for university counselling services.

Several factors are thought to be contributing to such issues, like greater school pressures and the effects of social media and cyberbullying. There have also been austerity-related cuts to youth workers and early intervention services, with an increasing proportion of children also growing up in poverty.

While our study can’t separate out these effects, it’s interesting to see similar concerns in other countries about the mental health of young people – including in Scandinavian countries, where overall levels of wellbeing are generally higher, and child poverty much less common.

So what can and should be done?

Part of the solution is clearly greater capacity and coordination of CAMHS within the NHS. In July 2018, the Care Quality Commission reported that the CAMHS system as a whole was “complex and fragmented”, and that “as a result, too many children and young people have a poor experience of care and some are unable to access timely and appropriate support”.

While the recent increased investment in CAMHS is to be welcomed, recent data from NHS England suggest that seven in every 10 children and young people with mental health conditions are still not getting the specialist support they need, with a target to reduce this to 6.5 out of 10 by 2020/21. While the aspiration of reducing these levels is the right one, we quite rightly wouldn’t accept these levels for children with a physical health problem, so why should we accept them for mental health conditions?

If we’re serious about ‘parity of esteem’ between physical and mental health, then much more ambitious targets and increases in resources are needed.

At population level, we also need to take the idea of generational inequality seriously, and look much more broadly at the environment in which children and young people are growing up.

A recent study by the Health Foundation highlighted the particular challenges faced by the current generation of young people in moving from childhood to a successful, financially independent adult life. These practical challenges were exacerbated by a lack of emotional support, with only 49% of participants reporting they got the emotional support they needed when growing up.

So one important step forward would be to support initiatives to educate and empower everyone in contact with children and young people (from young people themselves, to family members, school teachers, youth workers, and others) to provide such emotional support, and to understand when a referral to a GP or CAMHS professional is needed.

Such steps are vital if we’re going to start giving the mental health of our children and young people the priority it deserves.

*Dougal is the co-author of a journal article published in today’s Psychological Medicine titled Mental health and well-being trends among children and young people in the UK, 1995 – 2014; analysis of repeated cross-sectional national health surveys.

His co-authors on that article are Jacqueline Pitchforth and Katie Fahy (University College London), Professor Tamsin Ford (University of Exeter), Professor Miranda Wolpert (University College London and Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families) and Professor Russell Viner (University College London).

Suggested citation

Hargreaves D (2018) "Minds matter: time to take action on children and young people’s mental health", Nuffield Trust comment. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/minds-matter-time-to-take-action-on-children-and-young-people-s-mental-health