I was in Lisbon last week to speak at a chronic disease workshop run by the National School of Public Health. Both the English and the Portuguese health services currently face a significant funding squeeze, and policymakers in the two countries see chronic diseases as an area ripe for potential cost savings. However, in Portugal the focus is on different chronic diseases from those on which we concentrate in this country. Moreover, the emphasis in Portugal is on reducing the expected costs of these chronic diseases, whereas in the UK we tend to focus on preventing the unplanned costs of care.

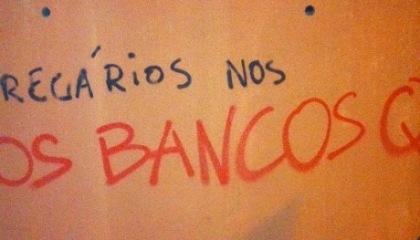

One of the first things that struck me on arriving in Lisbon was the amount of anti-capitalist and anti-banker graffiti that now adorns the city’s buildings. I arrived the day after the country’s biggest general strike in recent history, and the next day the Portuguese parliament passed a swingeing austerity budget - a budget that will reduce the nation’s deficit from 7.3 per cent of GDP today, to 4.6 per cent of GDP within a year.

Anti-banker graffiti daubed on Lisbon’s public buildings

Set against this harsh economic backdrop, the chronic disease workshop began with a sobering talk from a ministry of health official, in which she set out the challenges that the Portuguese NHS now faces. Many of the images and charts she showed in her presentation would have been familiar to a UK audience. However, whereas in Britain we typically concentrate on the “big five” chronic diseases (diabetes, heart failure, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or COPD, asthma and coronary heart disease), the two chronic diseases that are exercising the minds of Portuguese policymakers are chronic kidney disease (CKD) and HIV/AIDS.

For various reasons, both these conditions are particularly common in Portugal. Amongst OECD countries, Portugal has the third highest prevalence of people receiving dialysis (90 per 100,000, compared with 40 per 100,000 in the UK) and it has the highest HIV/AIDS incidence in Europe (with 51.7 new cases per million of the population per year—almost five times higher than incidence in the UK).

An interesting feature of both CKD and HIV/AIDS is that the costs of these conditions are relatively inexorable. For example, the cost of haemodialysis is about £30,000 per patient per year, and a person newly diagnosed with HIV will use about £300,000 worth of antiretroviral drugs.

This contrasts starkly with the costs of the UK’s “big five” chronic diseases, which relate largely to unplanned hospital admissions. COPD, for instance, can be relatively cheap to manage in the community because COPD drugs are relatively inexpensive. However, once a patient’s condition exacerbates to the point of requiring unplanned hospitalisation, suddenly the costs of COPD begin to soar.

The NHS in England is developing an enviable reputation for predicting and preventing these unexpected costs, particularly in the fields of predictive risk modelling, telehealth and multidisciplinary case management. One of the reasons we can do this in England is that the HES database allows analysts to track individual patients’ costs across different episodes of care over time. This is difficult or impossible in Portugal where there is no unique NHS number with which to track patients — hence the emphasis on expected costs, which are easier to estimate.

Nevertheless, there is probably a great deal more that we could be doing in the UK to tackle diseases such as CKD and HIV/AIDS whose expected costs are so high. For example, there were 2,500 patients newly diagnosed with HIV in the UK this year. Between them, these people will cost the NHS over £1 billion over their lifetimes. The focus for such conditions must be on improved primary prevention. For HIV/AIDS this will require better educational campaigns and increased testing. With CKD, the majority of cases are caused by hypertension or diabetes, so better prevention, detection and management of these conditions will be imperative.

The public health White Paper published this week announced that public health departments will soon transfer out of the NHS into local authorities. Whilst this offers a number of exciting opportunities for improving population health, it will be important to maintain a strong voice for primary prevention within the health service itself.