Hospitals are complex organisations, so explaining how and why performance varies between trusts is rarely straightforward. For rural trusts which have ‘unavoidably small’ hospitals due to their remote locations and thus cannot benefit from economies of scale, the level of under-performance appears stark.

As we reveal in our new report, for the seven trusts identified by NHS England as having such hospitals, there are some striking illustrations of this. Performance varies, and while two of the trusts do better than the national picture for A&E waits, on average across the seven trusts we found:

- a 5.5 percentage point poorer performance against the A&E four-hour target

- a 6.5 percentage point poorer performance against the 18-week elective wait measure

- 37 more delayed days per 1,000 admissions

- £27.8 million higher deficits.

Six of these seven trusts also ended 2017/18 in deficit, with their combined financial position amounting to a quarter of a billion pound deficit. Although they make up only 3% of all trusts, this represents almost a quarter (23%) of the overall deficit for trusts in England.

Why might this be?

The difficulties facing rural services may not come as a surprise. It’s been suggested previously that a number of factors contribute to unavoidable costs for providing health care in rural areas. They include:

- difficulties in staff recruitment and retention, and higher overall staff costs

- higher staff travel costs and unproductive staff time

- the scale of fixed costs associated with providing services within guidelines, such as safe staffing level guidelines

- difficulties in realising economies of scale while adequately serving sparsely populated areas. In primary care, for example, one study suggested that a 10% increase in list size was associated with a 3% reduction in cost per patient.

There are also differences in local markets for land, buildings and labour, and other factors to do with remoteness and a sparse population.

Which are the seven NHS trusts with ‘unavoidably small’ hospitals?

■ Isle of Wight

■ Northern Devon Healthcare

■ North Cumbria University Hospitals

■ University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay

■ United Lincolnshire Hospitals

■ Wye Valley

■ York Teaching Hospital

Allocation decisions and their impact

In the early 1980s, the ‘market forces factor’ (MFF) adjustment was introduced to account for unavoidable variations in local allocations. While it did not make direct adjustments for specific rural factors, in the 1990s an additional adjustment was brought in to do that – reflecting the higher costs of providing emergency ambulance services in rural areas, due to longer travel times – and a further small additional uplift to allocations was added three years ago.

The outcome of the complex formulae to allocate NHS funds to local areas is a zero sum game – it is an exercise in cutting up a fixed funding cake in the fairest way possible, not about changing the size of the cake. So, compensating for higher land costs in urban areas results in a reduction in allocations to other (e.g. rural) areas.

The allocation process involves two stages. First, target allocations are calculated – which start with the size of population in each area and then make adjustments for their health needs, levels of health inequality and unmet needs, unavoidable costs (market forces factor), remoteness (the unavoidable smallness adjustment) and rurality (the emergency ambulance cost adjustment).

The second stage involves a decision about the ‘pace of change’ – how quickly local funding allocations will change in order to move to their target amounts. This is a matter of judgement and takes account of how local areas adjust to changes in funding.

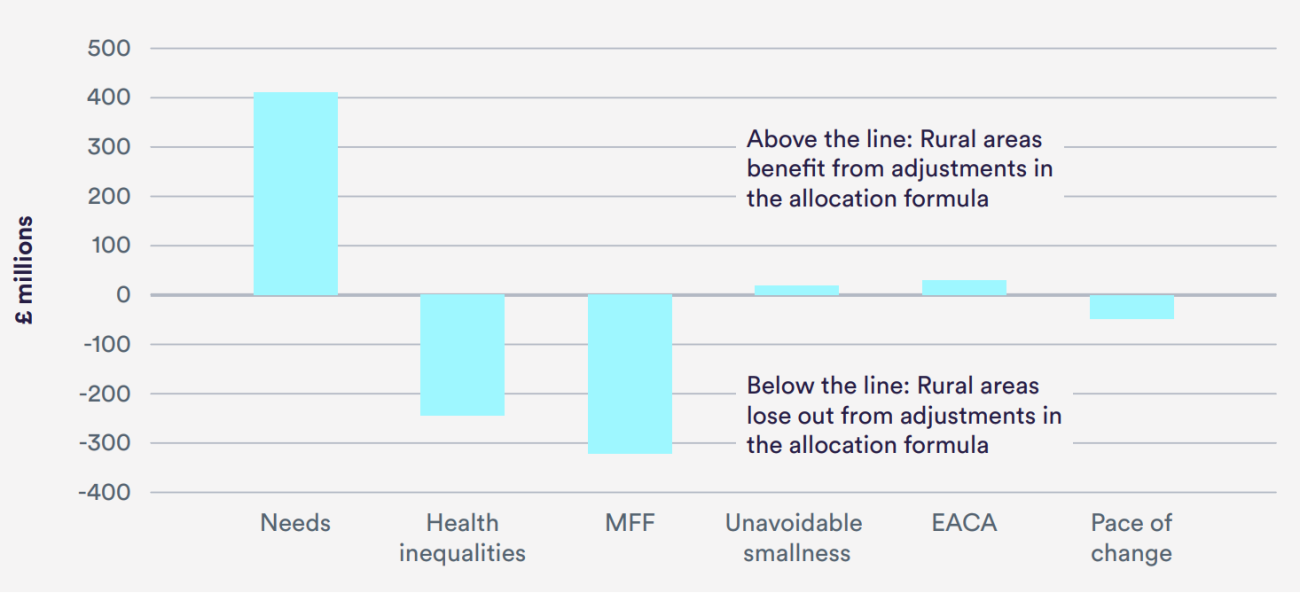

For the largest element of the NHS budget – the £74.2 billion for spending on core hospital and community services – some of the adjustments have the effect of moving large sums of money away from rural areas (see chart).

Judgement calls have a huge impact on core allocations for local areas. Such allocations are heavily influenced by the weight given to the adjustment for health inequalities and unmet need – which is not informed by evidence but remains a matter of judgement. This adjustment nonetheless has the effect of directing nearly £250 million from the target allocations of predominantly rural areas towards urban regions.

The scale of the adjustment for ‘unavoidable smallness’ appears very small and is limited to just acute hospital sites. Rural areas also continue to lose out due to allocations that, in part, reflect historical levels of expenditure that have tended to be higher in urban centres. While this ‘pace of change’ policy benefits allocations to rural areas for primary care, the converse is true for hospital services.

NHS England have announced revisions to the way funding is allocated to local areas from this April. They include changes in calculating need for community services, the market forces factor and the population data, which are hoped will better reflect the needs and costs in rural areas. Any improvements to the accuracy of the allocations are of course welcome, but this does not appear to represent a quick fix – the increase in allocations for predominantly rural areas next year is actually marginally lower than for urban counterparts.

Inconsistent funding to providers also an issue

Given the separation of purchasers and providers, the allocation of funding is directed largely at the former (clinical commissioning groups). For the specific rural adjustment to CCG allocations due to ‘unavoidable smallness’ (based on the remoteness of the providers from whom they commission services), the amount and method of compensation actually received by providers is opaque, and inconsistently applied to these seven remote trusts. For instance, York Teaching Hospital receives its CCG’s uplift (£2.8 million) in full, the uplift in tariff (prices) to University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay is equivalent to around four times the level the CCG receives, and other trusts receive no additional funding at all.

In addition, these trusts may be missing out on discretionary funding. For example, the seven in total received just 1.7% (£30 million out of £1,783 million) of the total allocation through the sustainability transformation fund in 2017/18.

How to improve approaches to funding rural services

A key theme from the report is a lack of transparency, which includes opaqueness around the basis for key assumptions that dictate significant shifts of funding around the country.

It also includes the lack of transparency about the decisions to agree – or far more commonly, reject – applications for additional funding for rural hospitals facing unavoidable additional costs. With a health service stretched to its limits, providers and commissioners in rural areas need a fair share of funding to be sustainable. The perception currently – as backed up by our work – is that some do not.

While we only undertook a rapid review, there appears sufficient evidence to prompt action. Some of our colleagues have previously pointed out that making rural services sustainable will require a number of solutions. Their recommendations included new staffing models and greater opportunities for more experienced trainees to practise more autonomously.

Similarly, our work on rethinking care in smaller hospitals recommended creating networks to better find the capacity to deal with urgent transfers, national bodies to improve how they recognise and respond to the needs of smaller hospitals, and supporting a broader skill set for the medical workforce.

In that light, we welcome the intention set out in the Long Term Plan for NHS England to work with smaller hospitals to develop a new operating model, recognising the workforce challenges they face and that many national standards and policies were not appropriately tailored to meet their needs.

More broadly, there needs to be an open discussion about how much additional expenditure we are prepared to spend to ensure equal opportunity of access to those at equal risk – a founding principle of the health service.

Suggested citation

Palmer W, Appleby J and Spencer J (2019) “The costs of delivering health care in rural areas”, Nuffield Trust comment. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/the-costs-of-delivering-health-care-in-rural-areas