In our report on the cuts to social care services for older adults we presented data which described a disquieting story: local authorities, which were already trying to match growing demand with inadequate budgets, have been forced to make deep cuts to adult social care services since 2010.

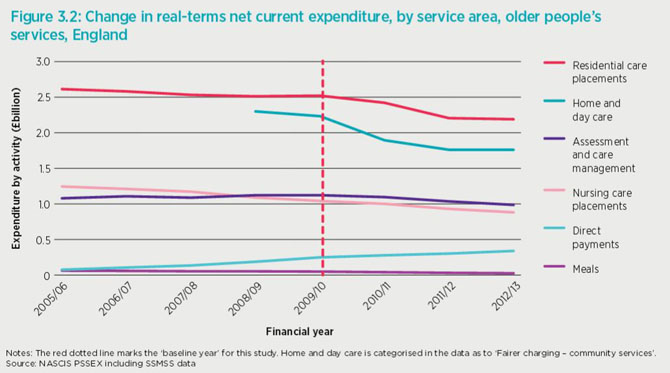

Between 2009/10 and 2012/13 net spending by local authorities on services for over 65s fell by 15% in real terms. Publicly funded social care was already heavily rationed by need and income – concentrated on those with the highest needs and lowest incomes.

This pattern of supporting those who need the highest levels of care seems to have accelerated as services in the community have been cut most (245,000 fewer adults received services in their own homes, such as meals, in 2012/13 than in 2009/10). But spending has also been reduced for those needing institutional care, resulting in more people having to pay for themselves.

Local authorities have also had to reduce the fees they pay to providers of services in care homes or care at home, which providers have had to absorb, often by cutting staff wages or reducing the length of visits to people’s homes.

Cuts are stimulating important policy initiatives

What impact is this likely to have had on people’s health and wellbeing? Given the scale of the cuts to services, it is alarming to find that the NHS does not routinely collect data on whether patients (or their carers) are users of social care, either funded by themselves or by the state.

Concern about the potential impact of social care cuts on the NHS is nevertheless driving important policy initiatives, including the NHS transfer of recent years and the more ambitious Better Care Fund, worth £3.8bn. The assumption – or hope – is that investment in joint working between social care and health will reduce pressures on hospitals, but recent press coverage of the Better Care Fund has reflected concern from the hospital sector that this investment represents a potential cut to their budgets, which may not in fact reduce pressures on beds and emergency departments.

Bringing both sides together

To explore the question of what impact the cuts have had on the wellbeing of users and carers – both older adults and adults of working age – we held a QualityWatch seminar which brought together perspectives from social care leaders and users.

Speakers included David Pearson, current president of the Association of Adult Directors of Social Services and Sue Brown of the Care and Support Alliance and the deafblind charity Sense. From the hospital sector we heard from Richard Kirby Chief Executive of Walsall NHS Trust (a medium-sized hospital in one of the most deprived areas of the Midlands) and Saffron Cordery, policy director at the Foundation Trust Network.

Speakers explained how lack of social care has created both visible and less visible impacts. Richard Kirby described the all-too-evident impact on his hospital’s ability to discharge patients who need support either at home or in a care home. Social care cuts have squeezed providers in his area to the point where there is no additional capacity: in one week last winter, his hospital had over 100 patients fit to be discharged with nowhere to go.

Fears over patient safety

Where there were once rows between the NHS and social care, this crisis has forced both sides into a dialogue about solutions, in this case prompting the community services arm of the acute trust to initiate intensive support for those patients most at risk of admission and readmission.

The discharge side of the equation may be more tractable than strategies for preventing admissions – these clearly worry many hospitals, which cannot close their doors to patients in crisis. And this is the real fear about the Better Care Fund – that it will take funding from acute hospitals faster than they can safely reduce their costs by closing wards and reducing staff.

These anxieties were reflected in the Foundation Trust Network’s recent polling, presented by Saffron Cordery: 67% of acute trusts thought that the Better Care Fund would have a negative impact on their trust’s finances, by removing funding for hospital services while models to divert people away from hospitals through better social and community support remain untested.

Making services stretch further

There are, of course, examples of innovative joint working between health and social care. These were presented by David Pearson, who believed that the current funding crisis facing both the NHS and social care was forcing leaders to walk in each other’s shoes and find creative ways of making services stretch further, often by making imaginative use of the voluntary sector.

Both David Pearson and Sue Brown reminded the seminar that a focus on the needs of older social care users threatened to obscure the very real and growing needs of working age adults with social care needs. There is a real risk that the NHS funding gap focuses too closely on older people at imminent risk of a hospital admission.

Tragic impacts happen away from the media spotlight

But the real tragedy of the social care cuts may not be felt immediately among those who’ve lost services and are facing private isolation as a result, away from the media’s spotlight on overcrowded hospital wards.

Sue Brown cited the story of one middle-aged deafblind service user, Catherine, who’d recently lost public support:

“Since my hours were cut I feel like I can’t be a proper mum any more. I don’t know if my girls are happy or sad unless the communicator-guide is there to tell me. I feel social services took my family life away when they cut my support”.

The cuts to social care services have been difficult to make for hard pressed social care departments across England. They have almost certainly had a big impact on the lives of thousands, but until users of social care (whether public or privately paid for) and carers can be easily identified by both NHS and social services, we can only guess at the full impact on people’s health and wellbeing.

- View Richard Kirby's presentation, Working together in the age of austerity

- View Saffron Cordery's prentation, Impact of social care cuts on NHS providers