Last week, all the major parties in England laid out their bids to be trusted with the future of the NHS. The bids were partly denominated in hard cash as each pledged higher spending. But observers could be forgiven for still having quite a few questions.

Why this amount? Is it enough?

There was a time when politicians did their best to ignore warnings about the financial squeeze facing the health service. When the Nuffield Trust warned of an emerging funding gap back in July 2014, Government minister Dan Poulter confidently said we were mistaken.

NHS England’s Five Year Forward View, coming as NHS trust finances continued to deteriorate, marked a turning point in attitudes. It gave a clear, accessible rationale for a certain amount of increased funding: in order to keep spending per person steady, adjusting for the aging population. This would require a roughly 1.5 per cent spending increase a year based on the current budget – or £8 billion by 2020. This is the source for the Conservative and Liberal Democrat spending pledges.

However, with more expensive drugs and pressure on staff pay pushing the bill up even further, that £8 billion would still require the NHS to find productivity savings of 2-3 per cent each year. This would be hugely ambitious for the economy as a whole , let alone health care, where heavy reliance on the human touch makes improving efficiency especially tough. David Nicholson, NHS England Chief Executive until last year, called it a “big ask”.

Labour announced their spending commitment earlier, in September 2014. They promised £2.5 billion in further funding as soon as possible in the next parliament, paid for by new taxes on “mansions”, tobacco companies and hedge funds.

At the time this “Time to Care Fund” was a bold commitment, and made Labour the first party to address funding beyond the election. But in the context of the Five Year Forward View’s vision of using new money to stabilise and support reform that we know cannot be done quickly, it looks too short term. Labour has been reluctant to adopt the £8 billion figure as its own – partly because of a determination to show that it is fiscally responsible . We would like to see them publicly accept what few informed sources now doubt: that the NHS will need at least this sum over the next five years unless patient care and waiting times are to deteriorate sharply.

Will the cheques come through when the NHS needs them?

The Forward View makes it very clear that the £8 billion needs to come as a “staged” increase. It must make up a shortfall equivalent to 1.5 per cent of the budget each year, and that means funding increases spread over the next parliament.

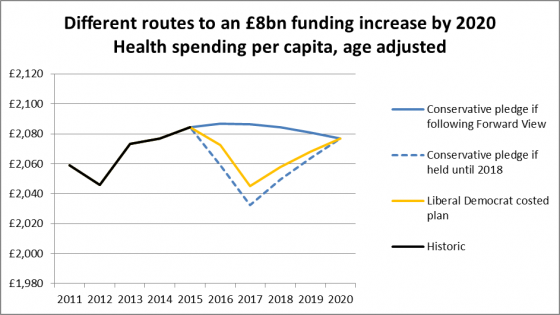

However, we know that the Lib Dems plan to focus their spending on the later years – they’ve been impressively transparent. This means they are actually committing around £6 billion less than the Forward View implies over the full five years, shown below.

Given the way that NHS providers are slipping into deficit, this would risk a situation where all the funding for those vital first years is eaten up by bail-outs instead of supporting new services. Experience also suggests that larger chunks of money spent quickly lead to poorer decisions and increased prices - a rebound effect which reduces the effectiveness of the spending.

The Conservative manifesto references the Forward View, which implies a steady increase, but it doesn’t quite make that promise. In fact, Jeremy Hunt has not even ruled out holding back the increases until after 2018/19. That seems unlikely given the sheer pressure on the NHS, but it would mean around £7.6 billion lower spending in total up to 2020/21 than the Forward View intended. That would create an intense squeeze on the health service, undermining all attempts at reform, and we urge the Conservatives to guarantee it will not be the case.

The chart below looks at what might happen to NHS spending per head by 2020 when we take into account population change. The Forward View implies a steady rise to £8bn per year by 2020 in each of the next five years. Any increase means the NHS budget grows in absolute terms. However, when we take into account the growing size of the population and the fact that, for example, a 65-year-old needs more healthcare than a 30-year-old on average, the £8bn increase is around what is required to keep the sum per capita flat.

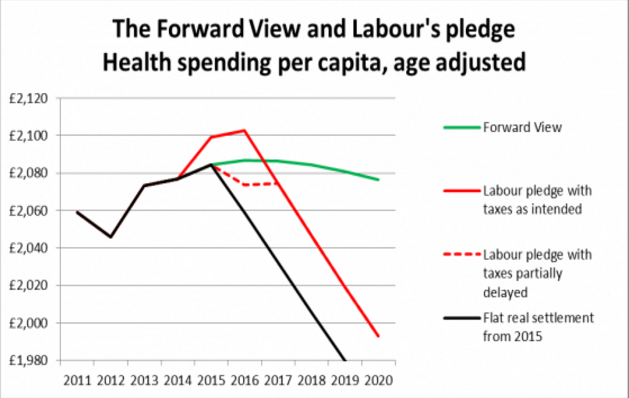

Labour is involved in a parallel but different argument about the timing of their pledge. They intend for it to come on-stream for the 2016/17 financial year. This would outpace the Conservatives’ pledge for that year even if the Forward View plan is adhered to. But Labour is not able to guarantee that the funding will be ready to spend in this year, and it may be partially delayed until 2017/18.

This is a dispute for tax experts, not a health care think tank, but it is important to keep the argument in perspective. The two below shows scenarios for spending per age adjusted person where the funding comes in on the timescale Labour want, and where it is mostly delayed to 2017/18, compared to a flat real settlement and to the Forward View £8 billion spending increase.

The timing makes the difference to whether they would overtake what the Conservatives appear to have pledged for 2016/17. But over the five year timescale on which we would like to see political leaders thinking, the difference is not that significant.

Who pays the price?

Given that all parties want a tight squeeze on the public finances, their answers on NHS funding raise the very important question of who will lose out so that the health service will gain.

In Labour’s case, we know the answer: its new taxes will cover the cost of its Time to Care Fund. The problem is, again, that these measures take us less than a third of the way to the lowest sum that the NHS will need by the end of the parliament.

The Tories’ £8 billion, meanwhile, is simply a free-floating promise, with no details of where it would come from and who will pay the price in deeper cuts.

Given the Conservative Party’s strong need to reassure voters on the NHS, and how visible the strain on the health service will be in the next five years, it would be difficult for them not to keep their word. The question is where the money will come from, and what the impact of that will be on the health service.

The 2015 Budget suggests the need for cuts of five per cent in public spending for 2016/17 and 2017/18 – a total of £40 billion. The Conservatives have tried to confound criticism by not spelling out where these will take place. However, the commitment to raise NHS spending, along with other pledges on pensions and schools, means they will be focused on a sub-set of services.

These include several services whose clients are both politically weak, and often reliant on the NHS. Social care for vulnerable older people has already been deeply cut this parliament. A leaked Civil Service document examining cuts of this magnitude identifies benefits for disabled people, and payments for carers, as candidates for cutbacks.

If these services and transfers are reduced, we might expect demand on the NHS to increase beyond what the Forward View anticipates - as it becomes for some people the public service of last resort. A&E and general practice is where this demand is most obvious – two parts of the system already under significant pressure.

Two weeks to go

We're just weeks from the General Election, and the time to ask questions is running out. It is important to keep doing so. If we reach May 7th without hearing the answers, we will only learn them as they happen – shaping a huge part of the British economy, our society and our individual lives for the next five years.

Suggested citation

Dayan M (2015) ‘The NHS bidding war’. Nuffield Trust comment, 21 April 2015. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/the-nhs-bidding-war