Eighteen months ago, the protection of NHS spending was not a popular position in Whitehall. Other departments, cut to the bone and facing more of the same, were envious. Politicians as different as Vince Cable, from the Lib Dem left, and Phillip Hammond from the Tory right, lobbied hard for the health service to “share the pain”. In Paris, the OECD called on the Government to reconsider the ringfence. In London, the staunchly pro-business Reform think tank called for it to go.

Yet last month all that seemed to have changed. As NHS England called for an £8 billion spending rise above inflation by 2020/21, hardly an objection was heard. George Osborne called the sum “conceivable”. The Financial Times made sympathetic noises. The director of Reform wrote a supportive article.

Why? Partly the new mood reflects faith in NHS Chief Executive Simon Stevens’ determination and ability to make sure the service uses the money it gets to best effect. But it also reflects a highly influential argument made by NHS England and sympathetic voices in government. This says that considering health spending as “flat” simply because it is the same as last year is misleading: the population whose health needs must be met from that budget is changing. There are more people each year and crucially, for health care, there are especially rapid increases in older age groups. In 2004, there were 270,000 men over 85 in England, while today, there are 440,000.

What you need to make an actual numerical comparison of health spending across the years is not just a count of the amount spent. For a more telling measure we divided that spending by the number of people, accounting for England’s growing population. Then we took account of the fact that they are moving into different age groups. With the help of figures kindly lent to us by NHS England, we were able to “age adjust” the population for each year. This means that if a person in an age group costs on average 20% more than someone in another age group, then a person in the costlier age group is counted as 20% more “population” to be treated.

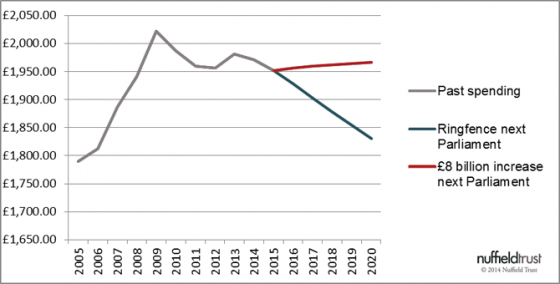

Our results underline why the health service has a case for feeling squeezed on a flat budget. The graph below shows English health spending per age adjusted person.

Up to 2010, the spending boom triggered by Labour’s policy of bringing NHS funding up to the Western European average easily outruns demographics. But with a frozen budget during austerity from 2010, spending per age-adjusted person fell by about £40 a head – ground not recovered despite 2013’s sizable increase of 2.4% above inflation.

And looking ahead, the fall in spending on this measure under a “flat real” ringfenced settlement looks clear. By 2020, the NHS would have £150 less for each age-adjusted person. Given that the much smaller fall so far since 2010 has seen serious pressures on NHS finances, and has been linked by some to pressures on waiting times, that should be enough to trigger a second thought from any would-be post-2015 minister.

Meanwhile, just as NHS England has implied, £8 billion is around the right amount to keep spending flat across a growing and aging population – leaving, perhaps, just a little extra.

It is important to remember, though, that politicians, competing to commit to tough deficit reduction targets next parliament, have been understandably reluctant to guarantee any such thing. The Tories have formally gone no further than a promise to “protect and invest” at least at a real terms settlement – although they point out that over this parliament, “ringfencing” has actually meant a £4 billion real terms increase.

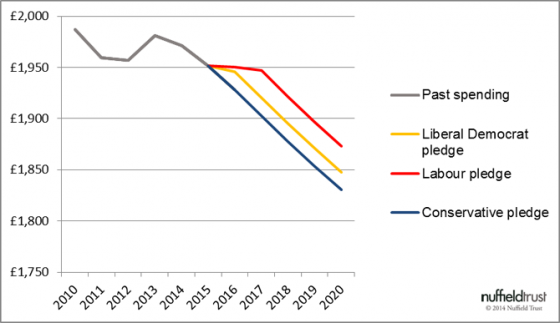

Labour and the Lib Dems both pledge major spending increases in the opening years of the next Parliament. The Opposition have pledged an extra £2.5 billion, which they intend to bring in each year from taxes on tobacco and high-priced housing. Nick Clegg’s party wants to increase NHS funding by £1 billion, and keep it there.

This graph shows the impact of these pledges up to 2020/21 (assuming Labour’s proposals take a couple of years for their tax take to reach £2.5 billion). It underlines the difficult implications of counting the patients when you measure trends in health spending. The growth in demand carries on, year after year. Pledges that seem ambitious in the short term don’t shift the lines.

And even if funding were to keep pace here, many other forces will continue to ratchet up the cost pressure. In the long run, the pay needed to get doctors and nurses to work in the UK will rise. We demand expensive new technology to keep up with outcomes in other developed countries. The argument for more investment in mental health and social care, the poor relations of physical health care, is strong.

By April next year, NHS spending pledges will be whistling back and forth over Westminster as political battle is joined. We should remember that this is only a brief exchange in a debate driven by trends which last decades. Conventional wisdom, and the limits of what is possible, will continue to shift as the pressures of an ageing society push on into the future.

Suggested citation

Dayan M (2014) 'The population time-bomb: can NHS spending keep pace?' Nuffield Trust comment, 19 December 2014. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/the-population-time-bomb-can-nhs-spending-keep-pace