Everyone wants to believe they have a doable job. But when I talk to finance directors at NHS trusts and foundation trusts, the imagery they use to describe their working lives is increasingly of feeling crushed and crunched, pinioned and pincered.

By describing how the NHS in England will struggle to meet the requirement to save £22 billion by 2020, and how extra efficiency from the provider sector may be required to close the resulting funding gap, the recent Nuffield Trust report Feeling the crunch: NHS finances to 2020 provides considerable insight into why these frontline NHS providers feel they are being asked to achieve the impossible. The report also leaves us with three questions: are the plans to save £22 billion sufficiently transparent; are the plans credible; and what is Plan B if we simply cannot save the required £22 billion?

In a way, it is hard to even assess whether the £22 billion savings plans are credible because relatively little is in the public domain, beyond the information provided to the Health Select Committee by NHS England in May 2016. This is part of the problem: you would expect an efficiency programme of this scale to be built on proposals that are openly shared, tested and agreed with the frontline providers who will have to implement them.

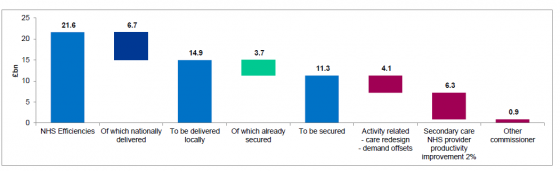

However, there is still enough in this publicly available information to cause concern. At the heart of the savings plan is the classic waterfall chart or ‘financial bridge’ that proposes how we will achieve the £22 billion savings target through:

- ‘national action’, such as maintaining caps on public sector pay and reducing central admin budgets

- ‘activity related’ actions to reduce the growth in demand for health care – let’s call that better commissioning

- ‘2 per cent provider productivity improvement’ so that frontline providers of hospital, ambulance, mental health and community services deliver more for less – let’s call that better provision.

Expected breakdown of the 2020 ₤22 billion efficiency programme remaining after 2016/17

The unfortunate reality check is that this financial bridge has some incredibly loose planks in it, and the consequences of a misstep are severe. NHS England's plan assumes that over £4 billion can be saved through actions to reduce the growth in the demand for health services over the next few years – by doing things like improving early diagnosis of conditions, supporting health promotion and disease prevention, and developing new care models that better link GP-led primary care and hospital-based care.

But the early indications are that these demand management initiatives take longer than we think to deliver concrete changes; are harder to implement than we think; cost more money in the early years than we think; and are effective on a smaller scale and patient population than we think. These new ways of working also seem focused on delivering greater value for the same level of NHS funding, rather than aggressively taking costs out of the NHS in the same way that closing hospital beds and reducing the size of the NHS workforce do.

As a result, none of the actions in this ‘better commissioning’ section feel like winning hands if you are in the ‘save money quickly’ game rather than the ‘improve value in the long term’ game. These actions also feel increasingly divorced from a world where the demand for services is heading inexorably up – a world where the number of patients admitted as emergencies through A&E departments has increased 6.4 per cent in the first quarter of this financial year compared to last year.

So, as Feeling the crunch notes, if you are not convinced that your demand management actions will close the funding gap, the spotlight inevitably starts to focus more tightly on asking frontline providers to improve the efficiency of how they deliver care.

No one would deny that NHS providers can and should continuously improve their efficiency. But we are reaching the point where simply asking the frontline ‘can you not try a little harder?’ is becoming untenable and even counterproductive. I always remember someone telling me how a senior consultant responded to a recent eye-watering savings target for their hospital department: ‘We’re bust. We were bust last year, we will be bust next year, and the trust down the road is bust too. So why are we trying so hard if we are going to be bust no matter what we do?’.

That is the risk we run if we continue as we are. When you have a stretching but achievable job it galvanises you to try harder. But when you have an impossible job, at some point you simply admit defeat and give up. So we can go one of two ways from here on in. We can maintain the current narrative of ‘we can close the funding gap by doing more for less’, or we can start a wider national and public debate on whether the NHS needs more funding to keep the show on the road, or whether it is time to start planning for ugly and difficult decisions on the universality, comprehensiveness or quality of the services the NHS offers.

If we continue with the ‘more for less’ trajectory, it is easy to see how we will move towards a system that slowly pulls itself apart into incoherence. Clinical commissioning groups who feel trapped between gold-plated NICE recommendations and tight controls on their annual finances will make individual local efforts to ration care that will be slapped down because they do not fit the national narrative. Providers who underspend on capital investment and staffing requirements to meet NHS Improvement’s financial targets will continuously worry about Care Quality Commission inspectors knocking on their door and reading from a very different hymn sheet. And every summer will be spent wondering if the Department has finally bust its budget. That is a lot of wasted energy compared to a system where there is a credible plan and core narrative for everyone to rally behind.

They used to joke that the Director of Finance at the Department of Health had a magic sofa, and when times got tough we could always find extra money for the NHS down the back of it. The extra £8 billion of funding the Department of Health, NHS England and the other arm's-length bodies won for the NHS was hard-fought in a time of austerity and should not be belittled. But the hard reality is that this is not enough extra funding to keep the NHS going. We do not live in a land of magic sofas of endless money and magic carpets that can cross wobbly financial bridges, and unless we stop pretending that we do, the NHS frontline will continue to feel crunched, pinioned and pincered.

Suggested citation

Anandaciva S (2016) ‘We might need a magic carpet to cross this financial bridge’. Nuffield Trust comment, 19 September 2016. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/we-might-need-a-magic-carpet-to-cross-this-financial-bridge