With five missed green paper publications, rumours of a white paper, and growing tension around the state of social care in England, it is no surprise that social care got top billing at Labour’s recent party conference. Among a number of pledges was a stark departure from our existing system: personal care for the over-65s, free at the point of use, funded by general taxation.

We have previously argued that general taxation as a means of financing a reformed social care system meets a number of key principles. But is free personal care the same thing as social care? And does making it free solve the problems that are all too clear with the current system?

What does personal care actually mean?

Reporting in the media has used a plethora of terms, with confusing headlines of ‘free social care’, or ‘free home care’. But free personal care does not cover all aspects of either of those.

Personal care specifically describes the delivery of physical and emotional care that is related to your person and is within your place of residence – whether that is your own home, a supported living facility, or a care home. It has been offered universally without cost to over-65s in Scotland since 2002 – a policy more recently extended to working-age adults.

Current Scottish legislation provides us with the best indication of what could be covered under Labour’s offer. In Scotland, ‘personal care’ includes personal hygiene, continence management, food and diet management, assistance with mobility, counselling and support, simple treatments, and personal assistance. But this national consistency of offer was not established until 2005/06, before which there was wide variation across local authorities in the interpretation of what personal care actually meant.

Even with some nationally set criteria for personal care, research in Scotland has suggested that differences in interpretation by local authorities persist, accompanied by confusion among the public as to whether other services are provided free of charge.

Why is there so much confusion about what personal care refers to?

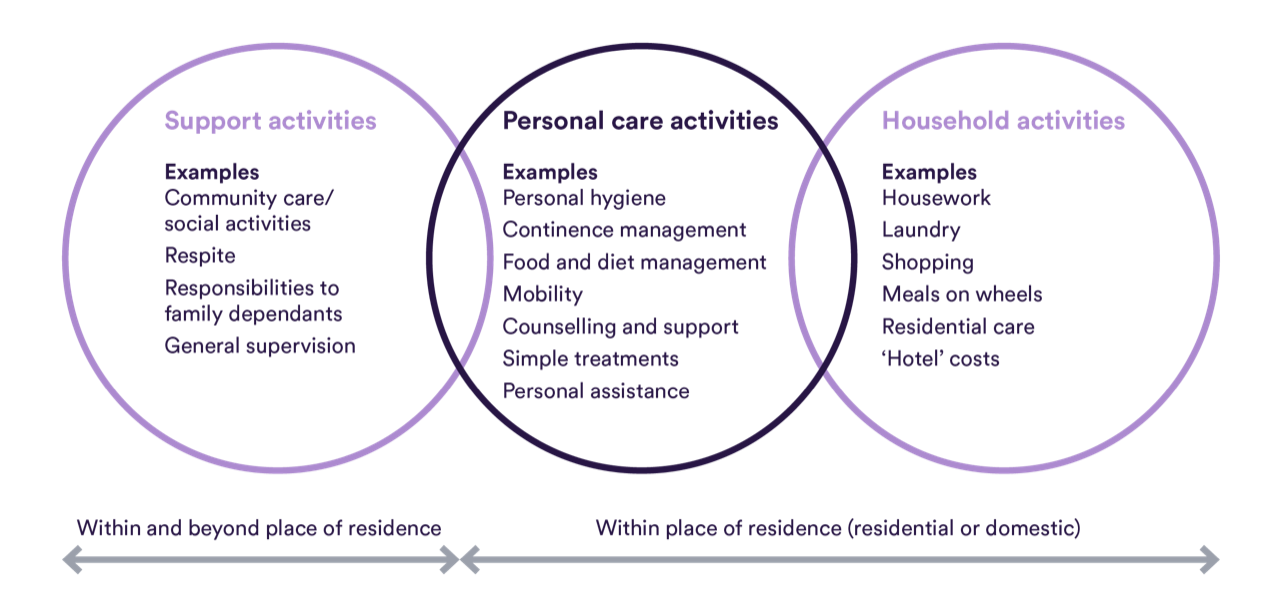

Perhaps this is best explained by the murky boundaries between personal care and other types of social care activities. In the below diagram, we map some common social care activities under some broad types and settings, following Scotland’s example. Only the ones that fall under personal care are currently free. Other main types of social care can include support activities outside people’s residences, and help with household activities that do not involve personal contact.

But in the real world, needs often fall across these boundaries. What would happen, for example, if you soiled your bedsheets? In theory, free personal care would cover costs to help you get out of bed and help you get cleaned. But following guidelines to the letter could also mean the rather absurd situation of the costs of changing your sheets not being covered – this technically being housework and laundry or ‘mopping and shopping’.

Similarly, as free personal care is not offered outside of your place of residence, attending social support activities such as community care would require you to fund a personal assistant yourself to help with your personal needs. In Scotland, both social support activities and the use of a personal assistant outside of the home are means tested.

Is free personal care the best use of state support?

Free personal care may not benefit everyone equally. Some older people with cognitive impairment and people with dementia may need general supervision to protect them from being prone to getting lost or having accidents like leaving the stove on, consuming spoiled food or handling sharp objects. This is not covered by free personal care, leaving people with dementia facing large bills, while people with other needs arising from old age (such as reduced mobility) would be receiving free care.

In Scotland, the extension of free personal care to working-age adults this April was hailed as a victory for equity and fairness. But critics have also warned that for as many as two-thirds of people under 65, free personal care would have no benefit at all. Their high levels of needs require activities outside personal care, for which the substantial charge still remains.

Why do definitions matter?

Where the state draws the line in terms of publicly funded support sometimes appears arbitrary, but the tangible consequences for individuals are real. It could mean being helped to clean yourself but not your bedsheets, or helped to prepare your meal but not to wash up your plate.

While the introduction of free personal care would be an encouraging step towards correcting our failing system, any government wishing to pursue this policy will need to give careful consideration to the language and definitions that are used and their heavy implications for service users.

The recent focus on use of language in political and public debates is important – for too long social care has been an opaque and confusing issue for people to understand. Our four tests set out that we need better clarity. We as the public need to better understand the pitfalls of our current social care system, so we can articulate how widely we want to define the vision for our future care.

Suggested citation

Oung C, Hemmings N and Schlepper L (2019) “What might Labour’s free personal care pledge actually mean?” Nuffield Trust comment.