Key messages

- Demographic and other drivers create an imperative to shift the balance of care from hospital to community. The NHS plans to undertake this transition while demand rises and it experiences the longest period of funding constraint in its history.

- There is widespread hope – both within the NHS and amongst national policy-makers – that moving care out of hospital will deliver the ‘triple aim’ of improving population health and the quality of patient care, while reducing costs. This has long been a goal for health policy in England, and is a key element of many of the Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) currently being developed across the country.

- Our analysis suggests that some STPs are targeting up to 30 per cent reductions in some areas of hospital activity, including outpatient care, A&E attendances and emergency inpatient care over the next four years. Yet this is being planned in the face of steady growth in all areas of hospital activity – for example a doubling of elective care over the last 30 years.

- This report provides insight from evidence on initiatives that plan to support this shift in care. Drawing on a review of the STPs and an in-depth literature review of 27 initiatives to move care out of hospital, we look at what their impact has been, particularly on cost, and what has contributed to their success or otherwise.

- Many of the initiatives outlined in this report have the potential to improve patient outcomes and experience. Some were able to demonstrate overall cost savings, but others deliver no net savings and some may increase overall costs. Where schemes have been most successful, they have: targeted particular patient populations (such as those in nursing homes or the end of life); improved access to specialist expertise in the community; provided active support to patients including continuity of care; appropriately supported and trained staff; and addressed a gap in services rather than duplicating existing work.

- Nonetheless, in the context of long-term trends of rising demand, our analysis suggests that the falls in hospital activity projected in many STPs will be extremely difficult to realise. A significant shift in care will require additional supporting facilities in the community, appropriate workforce and strong analytical capacity. These are frequently lacking and rely heavily on additional investment, which is not available.

- We argue that NHS bodies frequently overstate the economic benefits of initiatives intended to shift the balance of care. For example, they may use prices to calculate savings rather than actual costs and can therefore wrongly assume that overhead or fixed costs can be fully taken out. Similarly, many underestimate the potential that community-based schemes may have for revealing unmet need and fuelling underlying demand.

- The implementation challenges involved in shifting care out of hospital are considerable and even initiatives with great potential can fail. This is often because those responsible for planning and implementing them do not take into account the wide range of system, organisational and individual factors that impact upon their feasibility and effectiveness. Many schemes rely on models to identify ‘at risk’ groups that are often deficient and fail to adequately identify patients genuinely at risk of increased hospitalisation.

- Many initiatives we examine place additional responsibilities upon primary and community care, at a time when they are struggling with rising vacancies in both medical and nursing staff, and an increasing number of GP practices are closing. Addressing these issues is a necessary precursor to success.

- It is possible that many of the initiatives explored in this report have been too small and haven’t been supported by wider system interventions and incentives, and have therefore failed to shift the balance of care and deliver net savings. A more radical approach to the design and scale of the models being used might be required, but this will take time and resources to support the transition.

- While out-of-hospital care may be better for patients, it is not likely to be cheaper for the NHS in the short to medium term – and certainly not within the tight timescales under which the STPs are expected to deliver change. The wider problem remains: more patient-centred, efficient and appropriate models of care require more investment than is likely to be possible given the current funding envelope.

Shifting the balance of care

The NHS is undertaking a journey of transformation while experiencing the longest period of funding constraint in its history. It needs to close a £22 billion gap in its finances by 2020/21. At the same time, the underpinning fabric of social care is being dismantled, and a range of demographic and other factors are fuelling demand for NHS services. It is a herculean, and some might say impossible, task – made all the more difficult by the small amounts of available transformation funding now being used to prop up a system that is going further into the red.

The goal of delivering health care closer to people's homes is not a new one and has been an aspiration of numerous policy initiatives within the NHS for many years. In its most recent incarnation, 44 STPs, published in October 2016, describe how local areas aim to bridge the gap in NHS finances while delivering the vision set out in the Five Year Forward View. The plans need to find credible ways of coping with rising demand with no equivalent rise in funding. Many areas hope that moving care out of hospital will deliver the ‘triple aim’ of improving population health and the quality of care for patients, while reducing costs.

This report provides insights from the available evidence to help inform these local strategies. It aims to help local planners ensure that their assumptions are credible – currently the STPs include widely differing assumptions about the net impact on activity and cost. It also aims to help areas identify the initiatives that may deliver the greatest benefits locally and the key contributors to successful implementation.

We have grouped the evidence on the initiatives into five areas (although these are not mutually exclusive):

- Changes in the elective care pathway.

- Changes in the urgent and emergency care pathway.

- Time-limited initiatives aimed at avoiding admission or facilitating discharge from hospital.

- Managing ‘at risk’ populations including end-of-life care and support for people in nursing homes.

- Support for patients to care for themselves and access community resources.

We reviewed a large body of academic and grey literature, with a particular focus on robust evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs), Cochrane reviews and other systematic reviews, in order to draw on the most reliable evidence available. However, the quality of evidence on which we were able to call was mixed, and often reliant on poorly constructed evaluations.

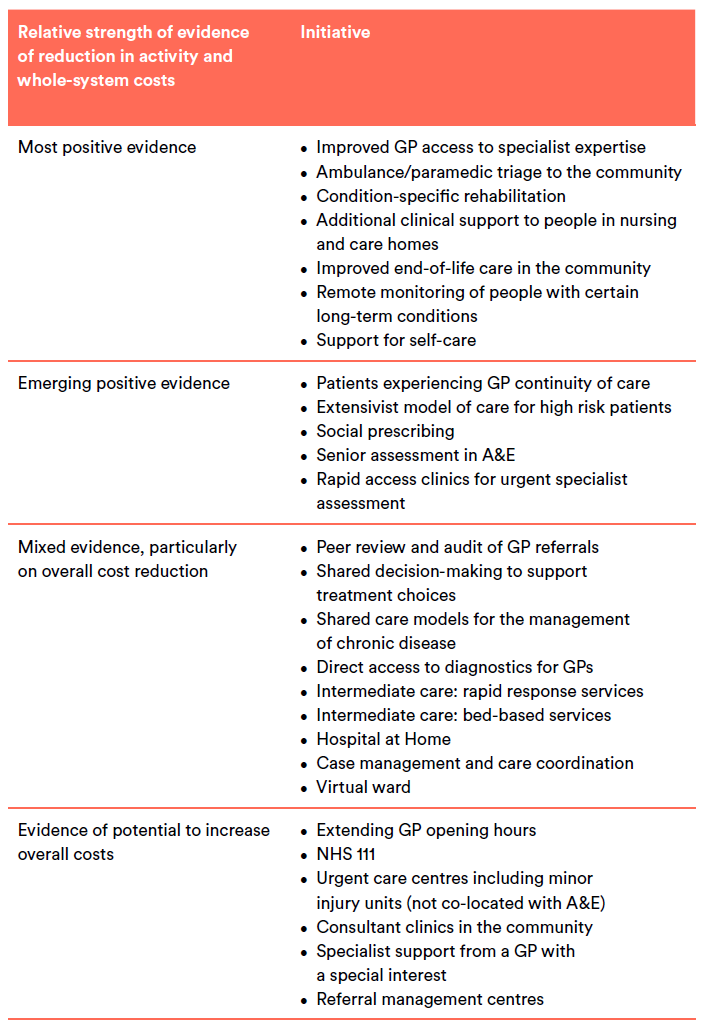

We focused on initiatives that were expected to impact most on areas targeted by STPs and those most frequently measured in research papers. The list of initiatives is long, but not fully comprehensive. Initiatives were selected based on a review of STPs and our knowledge of what health care organisations are implementing across the country. We put the initiatives into four categories: those where there is robust evidence to suggest an initiative improved care and was cost effective; those where there is emerging positive evidence; those where there is contradictory evidence; and those that have poor evidence or where there is evidence of increased costs.

Context – underlying activity trends

Rising patterns of hospital activity

We lay the evidence on initiatives to shift care out of hospital alongside analysis of the underlying trends in hospital activity, as well as other factors that would influence the implementation and impact of these initiatives.

Seasonal fluctuations aside, the last eight years have seen steady growth in all areas of hospital activity (Figure 1). Emergency admissions have risen by 14 per cent since 2008/09. For planned care, growth has been even sharper: elective admissions are up 22 per cent, while both GP referrals and first outpatient appointments have risen 26 per cent. This continues a longer-term trend of growth stretching back to the creation of the NHS.

These trends are likely to be magnified in future by demographic and epidemiological pressures. For example, the population of England is expected to grow by 4.4 million (7 per cent) and the number of people over the age of 85 by 0.5 million (33 per cent) between 2014 and 2024. Over a similar time period, the number of people living with dementia is expected to grow from 700,000 in 2014 to around 1.3 million in 2025.

STP assumptions on reducing hospital activity

Currently the STPs include widely differing assumptions about the impact that their local strategy will have on hospital activity and their underlying assumptions are often far from clear.

With this caveat, our interpretation of the material in the public domain is that in 2020/21 the STPs are predicting activity to be less than forecast (based on current trends) by the following amounts:

- 15.5 per cent fewer outpatient attendances (range 7–30 per cent)

- 9.6 per cent less elective inpatient activity (range 1.4–16 per cent)

- 17 per cent fewer A&E attendances (range 6–30 per cent)

- 15.6 per cent fewer non-elective inpatient admissions (range 3–30 per cent).

Only two thirds of STPs included an explicit risk assessment of these assumptions.

Summary of the evidence

Redesigning elective care pathways

There are a number of initiatives that aim to better manage elective care, the most promising of which is enabling GPs to access specialist opinion to help them manage patients in the community and avoid unnecessary referrals to outpatient services.

Peer review and audit of GPs’ referral patterns can improve the quality of referrals and may reduce the overall number of referrals to outpatient services. Shared decision-making, shared care models and direct access to diagnostics for GPs have well-evidenced benefits for patients and professionals, but less conclusive findings on their capacity to reduce hospital activity and deliver savings. There are also initiatives where the evidence suggests that they may increase overall costs. These include consultants working in the community, referral to a GP with a special interest and the use of referral management centres.

Any strategy to redesign elective care does so in the context of sharply rising outpatient attendances, sharply rising day case activity and slowly falling elective inpatient activity (as care shifts from inpatient care to day case and outpatient procedures). In addition, many of the initiatives that have

shown promise to date bring new expectations of GPs; nearly all require GP training or support. However, we believe there is significant scope in themedium to long term to redesign the elective pathway and deliver a more integrated model of elective care, with much more outpatient care delivered in primary care. A much more radical redesign of elective care underpinned by technology, including clinical decision support, and adoption of shared decision-making could yield savings.

Redesigning urgent and emergency care pathways

A range of initiatives aim to reduce attendance at accident and emergency (A&E) departments, with some also helping to avoid subsequent hospital admission. Our review of the evidence suggests that, of the approaches reviewed, ambulance/paramedic triage to the community has the strongest evidence to support it.

The effective implementation of schemes designed to reduce emergency hospital care is dependent on capacity in primary care and improved data-sharing between sectors. The schemes that require staff working in different ways will need to ensure that individuals are sufficiently trained and working within their sphere of competency, particularly where decisions about referrals are made. However, other initiatives have the complex task of trying to influence patients’ behaviour prior to their contact

with urgent or emergency services, or to prevent further use of services (i.e. extending GP opening hours, NHS 111 and urgent care centres which are not co-located). Successfully changing patterns of service use requires access to appropriate and timely primary care, as well as high levels of trust in these alternative services.

Trends in use of A&E, and the significant increase in attendances in 2003 following the introduction of minor injury and specialist services, highlight an important consequence of the initiatives described in this section: supply-induced demand. Many of the initiatives we looked at increased contacts with the NHS without equivalent reductions in the use of A&E. In some cases, this has increased overall costs.

Avoiding hospital admission and accelerating discharge

Over the last 30 years the number of hospital beds has more than halved. At the same time, hospital admissions have been rising, particularly for older people. Bed reductions have been possible because of a reduction in length of stay and a shift from inpatient care to day case and outpatient care. Despite these bed reductions, some estimates suggest that up to 50 per cent of beds are occupied by people who could be cared for in community settings.

Of the evidence reviewed, the initiatives with the most positive outcomes are those for condition-specific rehabilitation. Pulmonary and cardiac rehabilitation improve quality of life and reduce hospital admissions, and have been shown to be cost effective. There is emerging positive evidence for rapid access clinics and senior decision-makers in A&E, but further research is needed, particularly around their economic impact.

Evaluation of rapid response teams and the use of intermediate care beds shows much more mixed results, suggesting that local implementation and context play a large part in their success. Clear referral criteria and good integrated working across health and social care appear to be important.

Hospital at Home schemes successfully provide a safe alternative to hospital, but there is little evidence that they deliver net savings.

Absence of evidence is not necessarily a sign that a particular initiative would not work if introduced in an appropriate context. What is clear is that to avoid hospital admissions and accelerate discharges, there must be sufficient capacity and funding of alternative forms of care in the community. Without this investment, analysis suggests that the NHS will need to expand, not contract, its bed capacity.

Managing ‘at risk’ populations

A large number of diverse initiatives over the last two decades have aimed to better manage ‘at risk’ populations, but while services are highly valued by patients, very few have successfully reduced hospital activity. The strongest evidence relates to those initiatives that target well-defined groups; that is, those in nursing and residential homes, and those at the end of life. There is growing evidence for initiatives that monitor people at home, particularly for some conditions such as heart failure. The extensivist model, which provides holistic care for those at greatest risk, has promising evidence from its use in the US, but its benefits have yet to be formally demonstrated in England. The initiatives which have the greatest challenge in demonstrating impact on hospital activity, but have other positive benefits for patients and their experience, are more general attempts to case manage those deemed to

be at highest risk of admission, including the use of virtual wards.

There are several reasons for this lack of impact or cost savings. First, efforts to coordinate care involve initiatives to correct underuse and ensure timely access to care. In isolation, these efforts tend to increase the use of care, at least partially negating any reductions in preventable or unnecessary care resulting from coordination. Second, for every costly complication prevented, a care coordination programme must manage multiple patients at risk of such a complication, even if it selectively targets high-risk patients. And third, care coordination is costly. The cost of staff and other resources can offset the savings from the hospital care avoided.

Maximising impact on hospital use requires accurately targeting initiatives at the groups most likely to benefit, and where a reduction in admission will have most impact on resource use. Risk stratification tools still struggle to identify ‘at risk’ individuals at the point before they deteriorate.

Trends in life expectancy and the number of people with multi-morbidities suggest that the number of ‘at risk’ people will continue to rise, making it an even greater imperative to manage this group better. The lesson from the evidence is that significant attention needs to be paid to the accurate targeting of initiatives, while moderating expectations of their capacity to reduce overall cost.

Support for patients to care for themselves and access community resources

There are 15 million people living with long-term conditions and over two million with multiple long-term conditions. Together they account for 55 per cent of GP appointments and 77 per cent of inpatient bed days. Receiving support to help them manage their conditions may result in reduced crisis points and less costly care. However, despite the positive evidence for selfcare, there remains a lack of clarity about which elements are most effective. Assessing the impact of social prescribing presents significant challenges as it encompasses highly diverse initiatives for a wide range of needs, and its benefits go beyond reduced resource use. But the growing evidence base is positive.

Both support for self-care and access to community resources require behaviour change on the part of patients and professionals; moving from a model in which the patient is a passive recipient in the traditional medical model, to a treatment programme that is based around engagement and active participation. Self-care requires significant infrastructure and professional support to improve health and digital literacy, as well as encourage engagement. Programmes that are well-supported, funded

and given sufficient time to develop are most likely to demonstrate benefits. Given the many millions of people managing one or more long-term condition, the scale of what is required to realise the full potential in this area is considerable.

Implementation and other challenges

The challenges in implementing the sorts of initiatives we have analysed are considerable and even those with great potential can fail. This is often because the wide range of system, organisational and individual factors that impact feasibility and effectiveness are not taken into account. The proposed shift in care cannot be achieved without significantly increasing capacity and capability in primary and community care, and solving some of the prevailing social care problems.

A major challenge is workforce. The NHS is trying to grow services where clinical workforce numbers have fallen and disinvest in services where clinical workforce numbers have grown. For example, between 2006 and 2013, the number of consultants in hospital and community services grew by 27 per

cent, while the total GP workforce rose by only 4 per cent and the number of GPs per capita fell. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of district nurses fell by 35 per cent.

There are large and growing gaps in the clinical workforce, particularly in the services facing some of the most acute demand pressures. A third of GP practices have a vacancy for at least one GP partner. There are vacancy levels of over 21 per cent for district nurses. It is questionable whether there is the

workforce – in terms of numbers, skills and behaviour – needed to deliver these initiatives.

Many of the models being used within the NHS to identify ‘at risk’ groups (such as people who are frequently admitted to hospital) are frequently deficient and those using them are often too optimistic in their assumptions about the impact of targeting high-risk groups.

The NHS as a whole also has a tendency to view problems through the lens of a single condition (e.g. diabetes). The complexity that stems from multi-morbidity is frequently not well understood or addressed. This lack of understanding of a person’s entire health and social care needs, and service use, leads to unrealistic assumptions being made about the potential impact of an initiative.

There are particular challenges in delivering economic benefits. A number of factors inhibit the delivery of system-wide savings. The use of prices to calculate savings rather than actual costs and a tendency in modelling the costs of services to assume all the overhead or fixed costs can be fully taken out, can mean that real-world savings are significantly over-estimated. There is also the risk of supply-induced demand; any strategy that aims to reduce over-use is also likely to identify under-use and unmet need.

The challenge of demonstrating economic benefits is part of the broader issue of the way in which success is measured. While initiatives may not deliver savings, they may increase ‘value’ by addressing unmet need, or encouraging need to be met in ways that deliver better outcomes for people. Bundles of initiatives and multifaceted programmes targeting high-risk populations are likely to be more effective than those involving single approaches, yet single initiatives are most often implemented and measured.

Also, initiatives are not given long enough to take effect. A key feature of so-called ‘transformational’ change is the length of time it takes. Yet policymakers frequently want instant results. The STP process is a case in point here – one of the biggest shifts in how the NHS delivers care for a generation is expected to be completed within five years.

A further complicating factor is that in-hospital and out-of-hospital care are not on an equal footing when it comes to investment in staffing, infrastructure and the elusive but important issue of prestige. And despite the considerable pressures they are facing, hospitals have the infrastructure and payment systems to enable continued investment, while the same cannot be said for care out of hospital. This makes the goal of transferring care out of hospital all the more challenging.

Finally, a vital facilitator of all of the above is strong analytics and shared data. This is essential if the problems are to be correctly diagnosed, the solutions appropriately targeted and their impact evaluated.

Conclusion

Our research has shown that despite the potential of initiatives aimed at shifting the balance of care, it seems unlikely that falls in hospital activity will be realised unless significant additional investment is made in out-of-hospital alternatives.

Where schemes have been most successful, they have: targeted particular patient populations (such as those in nursing homes or the end of life); improved access to specialist expertise in the community; provided active support to patients including continuity of care; appropriately supported and trained staff; addressed a gap in services rather than duplicating existing work.

Implementation and contextual factors cannot be underestimated, and there needs to be realistic expectations, especially around the economic benefit of new care models. If STPs continue to work towards undeliverable expectations, there is a significant risk to staff morale, schemes may be stopped before they have had a chance to demonstrate success, and gains in other outcome measures such as patient experience may be lost.

There are a number of areas where STPs can learn from previous initiatives:

- Measures should be taken to really understand patient needs and what adds value, rather than using activity as a proxy for demand.

- More effective risk stratification and linked data should be used to identify genuinely high-risk patients and avoid ‘regression to the mean’ (whereby patients identified as high risk at a point in time do not meet this characteristic when analysed over a longer time period).

- Robust data and analytics to support change are essential.

- Staff need improvement methods that they can use, and support in implementing changes. Support from frontline managers, as well as leadership from the top, is vital.

- A workforce strategy is needed to ensure that staff are equipped with the competences required by the new models.

- A whole-system perspective needs to be taken when assessing the cost effectiveness of initiatives, including a realistic assessment of the capacity to disinvest in hospital and other services.

None of the above detracts from a significant challenge that this work poses to local and national planning assumptions. Shifting the balance of care from the hospital to the community has many advantages for patients, but is unlikely to be cheaper, certainly in the short to medium term. These findings echo the National Audit Office’s recent conclusion that current attempts at integrating services provide no evidence that integration will save money and reduce hospital activity.

Any shift will also require appropriate analytical capacity, workforce and supporting facilities in the community. Currently these are lacking. And the wider problem remains: more patient-centred, efficient and appropriate models of care require more investment than is likely to be possible given the current funding envelope.