The ambulance service has come to be a totemic symbol of the NHS in England, free at the point of use and available to all. It represents the fundamental duty of care at the heart of the health service and is an expression of the dedication of NHS staff. But as Prof. Keith Willett, NHS England’s Director of Acute Episodes of Care, powerfully described at a recent House of Commons Public Accounts Committee evidence session, working in the ambulance service is a difficult and often stressful job:

“We have to recognise that paramedics and ambulance technicians work in isolation a lot of the time. They face high violence and assault rates and work in very difficult environments. They make decisions on their own; they haven’t got somebody senior to turn around to or pick the phone up to.” (Oral evidence to Ambulance Services Study, 20 March 2017, Q155)

In addition, ambulance services, like other parts of the NHS, have faced growing pressures over the last few years as the increase in funding has slowed while at the same time patient demand has grown. The ambulance service has worked harder than ever – Category A calls (those involving life-critical and very urgent incidents) resulting in an ambulance at an incident have increased by a third in the last five years. But headline response times have suffered and the morale of staff remains among the lowest of all the NHS workforce.

In our final winter briefing, we look at these growing pressures on a critical NHS service.

Supply struggling to keep up with demand?

Demand for the activity of services provided by ambulance trusts – from urgent calls to basic patient transport to responding to calls passed from NHS 111 – has been increasing over the last five years, growing faster than the growth in ambulance staff numbers. Activity has also grown faster than for secondary care activity such as emergency admissions and accident and emergency attendances.

In 2011/12 the total number of emergency and urgent calls (excluding calls passed from NHS 111) was 8.2 million. By 2015/16 this had risen by over 15 per cent to 9.4 million – an average annual increase of 3.6 per cent. But at the same time, the number of Category A calls resulting in an ambulance arriving at the scene of an incident rose by 33 per cent, from 2.5 million to 3.3 million – an average yearly increase of 7.4 per cent. This suggests that the service has not only been taking more calls overall, but that demand relating to more serious and urgent cases has risen.

This is also reflected in the breakdown of Category A calls – into Red 1 and Red 2, which began in 2012/13. Red 1 (the most time critical, which cover cardiac arrest patients who are not breathing and do not have a pulse) responses have increased by 53 per cent during this time. Red 2 (less serious, but still urgent) responses also rose by 47 per cent.

All these increases contrast with an average annual increase of 2.1 per cent in emergency admissions and a 1.6 per cent increase in attendances at emergency departments between 2011/12 and 2015/16.

While calls and responses have increased markedly over the last few years, so too have the number of ambulance staff, but at a slower rate. Between 2011/12 and 2015/16, the total number of staff increased by around 8 per cent – from 36,200 to 39,000. However, excluding managers, estates and clerical staff, the number of paramedics and technical assistants only rose by 3 per cent (from

25,800 to 26,600).

The picture is one of calls to the emergency services outstripping population growth and the number of staff, and perhaps at the same time becoming more serious.

But in responding to the volume of demand, has there been a cost in terms of quality of care for patients?

Targets and quality: Hit and miss?

A key measure of the quality and performance of the ambulance service is the time taken to respond to emergency calls. Given the nature of the demand, speed of response is of the essence.

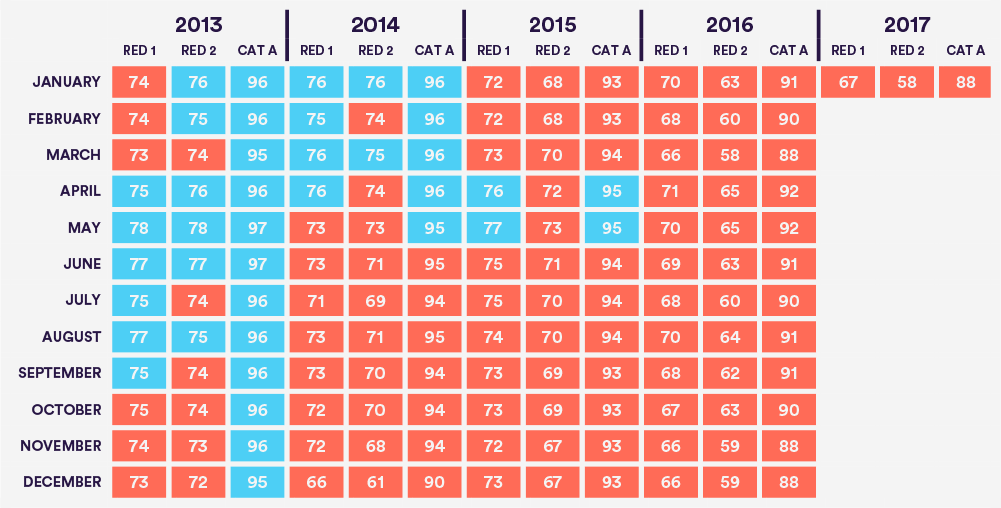

Currently, the ambulance service in England works to three main response time targets (see Box 1). Despite their importance, all three have only been met in six out of the last 49 months, and none have been met since May 2015.

Box 1: Three headline ambulance response time targets

Currently the ambulance service in England has three main response time targets based on the urgency of the calls received. 95 per cent of all Category A calls must receive a response with an ambulance at the scene of the incident within 19 minutes. Category A calls are split by urgency and seriousness into Red 1 (the most time critical, and cover cardiac arrest patients who are not breathing and do not have a pulse) and Red 2 (less serious, but still urgent).

Red 1 and 2 calls have an additional target: 75 per cent of Red 1 and Red 2 calls must receive a response with an ambulance at the scene of an incident within eight minutes.

As Figure 1 on page 4 shows, performance nationally across all these targets has deteriorated markedly over the last few years. The latest results for January this year show that just 67 per cent of Red 1 and 58 per cent of Red 2 calls received a response within eight minutes – significantly missing the target of 75 per cent.

And of the 233,472 Category A calls received in January this year, at least 95 per cent should have had a response within 19 minutes. But in fact 29,000 calls did not receive a response within 19 minutes, meaning only 88 per cent of responses met the standard.

However, despite increased demand and pressures on the ambulance service, it is encouraging that on some key clinical performance measures, ambulance trusts have been performing reasonably well. For example, on specific clinical indicators for calls concerning heart attack and stroke, performance has either improved very slightly or remained relatively flat over the last four years.

Moreover, ambulance services are increasingly dealing with calls following telephone advice to callers – obviating the need to dispatch an ambulance. So-called ‘hear and treat’, where calls are resolved over the phone, have risen from around 334,000 in 2011/12 to nearly 677,000 in 2015/16 – more than doubling in just five years.

Ambulance diversions

As the recent National Audit Office report (NHS Ambulance Services, 26 January 2017) has highlighted, ambulance handover delays at hospitals are a huge problem, with the NAO calculating that last year around 500,000 ambulance hours were lost due to turnaround at A&E departments taking more than 30 minutes (the stipulated standard). However, less light has been shed on what happens when these delays become so great that trusts feel they have to temporarily close their emergency departments in the face of high demand and their assessment of the safety of patients attending A&E – resulting in the diversion of ambulances to other hospitals. This is not only problematic for the ambulance service, with ambulances ending up in the ‘wrong’ area to respond to new calls, but also of course for patients who are likely to have to spend more time travelling.

In exceptional circumstances, and only after consultation between local trusts, commissioners and the ambulance service, emergency departments sometimes find it necessary to temporarily stop accepting ambulances and instead divert them to other departments locally. Diverts are much more common in winter when emergency departments tend to be under more pressure.

On the impact of diverts, Richard Webber, a practising senior paramedic and national spokesperson for the College of Paramedics, has said:

“Diverts from A&E departments have an impact on paramedics’ ability to reach seriously ill and injured patients in an appropriate timeframe. While we are sympathetic to hospitals that are forced to implement diverts so that they don’t reach dangerous levels of overcrowding, in non-urban areas in particular the extra time taken to reach more distant A&E departments is significant. There is a ‘double whammy’ in that not only do crews have to drive further away once a divert is implemented – once that’s happened, an ambulance crew will then need to travel further to get back to their own area to respond to the next emergency call.”

From the weekly winter situation reports published by NHS England each year during the winter months, the number of such incidents has fluctuated between 225 in 2013/14 to 265 in 2015/16. However, last winter, 2016/17, the number of diverts was 478 – 80 per cent more than the previous year – an indication of mounting pressure on emergency departments and an added difficulty for the ambulance service in transporting patients (see Figure 2).

Geographically, the number of diverts across the whole of this winter has been unevenly distributed. Just over a third of trusts reported one or more periods of diversion this winter, and just five organisations accounted for around half of all the reported diversions during the winter – four in the north of England commissioning region (Pennine Acute Hospitals, Northumbria Healthcare, County Durham and Darlington, and South Tyneside) and one in the Midlands (Worcestershire Acute Hospitals).

Ambulance staff morale: taking a hit?

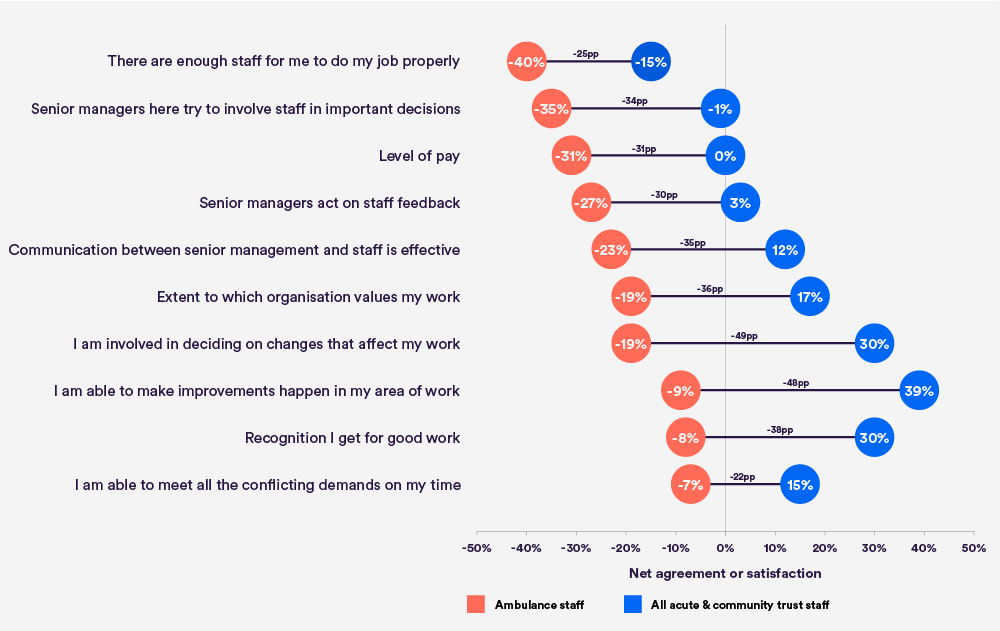

Even allowing for the inherently stressful nature of the job, the poor responses in the annual NHS Staff Survey from ambulance personnel are striking. Compared to all acute and community staff, ambulance staff tend to report feeling less satisfied or respond more negatively to most questions asked by the survey.

As Figure 3 shows, the top 10 questions on which ambulance staff report the worst net satisfaction or agreement highlight some fundamental problems with staffing, morale, pay and management. For example, asked whether there are enough staff to enable them to do their job properly, 21 per cent of ambulance staff agreed but 61 per cent disagreed (a net agreement of -40 per cent). And on pay, 24 per cent were satisfied with their level of pay, with 55 per cent dissatisfied (a net satisfaction of -31 per cent).

Of note is the often much poorer responses compared to most other NHS staff(the percentage point gap in net satisfaction/agreement as shown).

A further clear reflection of the difficult nature of the job and the issues of concern emerging from the Staff Survey is the fact that ambulance trust staff consistently have the highest sickness absence rates compared to all other types of NHS organisation.

Key issues

Given the evidence from recent performance against targets and the views of ambulance services staff themselves, there are three key issues the service needs to address: staffing, morale and management.

Staffing: A key issue for the ambulance service has been the lack of growth in staff numbers at a time of increased demand for emergency services. However, there are signs that this is changing. Between 2009 and 2014, the numbers of non-managerial and non-clerical staff remained virtually unchanged. But in the last two years numbers have risen by over 2,500. Despite this increase, as the results of the 2016 NHS Staff Survey indicate, staffing remains a top concern among ambulance staff.

Morale: As is clear from the results of the NHS Staff Survey (on pay, feelings that they are valued by their organisation and recognition for good work), morale among ambulance staff could not be said to be particularly buoyant. The effect on morale of the recent increases in ‘frontline’ staff numbers remains to be seen. But staff morale is hugely important, not just for staff themselves, but for the positive impact it has on patients’ experience and outcomes of care. Positive efforts to improve morale are therefore crucial.

Management: A striking result from the NHS Staff Survey is the relatively poor responses relating to management issues. From communications and feedback to feelings of worth and general involvement in changes at work, ambulance staff are consistently much less satisfied than their non-emergency colleagues in the NHS. Clearly there is more to be done to engage ambulance staff – particularly at a time of funding pressures and service changes – and to improve those aspects of management staff currently feel adversely affect their attitudes to work.

Conclusion

As this short briefing has shown, the ambulance service is facing tremendous pressure in England. Rising demand for the service, particularly through an increase in the most serious 999 calls, has undoubtedly been a factor in the poor morale and high stress levels of the workforce. Furthermore, this winter has seen a striking increase in the numbers of ambulances being turned away from emergency departments, as pressure on the entire emergency care system has impacted on the NHS.

Despite this, ambulance services have maintained and even improved care quality in a number of key areas – from stroke care to heart attack, and innovations such as ‘hear and treat’ have enabled them to improve efficiency and manage the increased workload. Ensuring that this kind of innovation continues to progress will require a relentless focus on developing and nurturing staff and turning around the pattern of poor morale that has become widespread within the ambulance service.

References

NHS England (2017) Winter Daily Situation Reports 2016-17. NHS England. http://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/winter-daily-sitreps/winter-daily-sitrep-2016-17-data

NHS England (2017) Ambulance Systems Indicators Time Series. NHS England. www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ambulance-quality-indicators

NHS England (2017) Ambulance Clinical Outcomes Time Series. NHS England. www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ambulance-quality-indicators

NHS England and Picker Institute (2017) Staff Survey 2016 Detailed Spreadsheets. NHS England and Picker Institute. www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/Page/1019/Latest-Results/Staff-Survey-2016-Detailed-Spreadsheets

Public Accounts Committee (2017) Oral evidence: Ambulance Services Study, HC 1035. Public Accounts Committee.

http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/public-accounts-committee/ambulance-servicesstudy/oral/49148.html

National Audit Office (2017) NHS Ambulance Services. National Audit Office. www.nao.org.uk/report/nhs-ambulance-services