The recent cross-party parliamentary report on the NHS and social care workforce did not pull any punches in describing the staffing problems in the health service. Using Nuffield Trust estimates, the Committee notes that the NHS has struggled with 12,000 hospital doctor vacancies and more than 50,000 nurse and midwife vacancies. These figures are based on bespoke data provided by NHS England & NHS Improvement and NHS Professionals from May 2021. The estimates suggest that, if anything, the existing published data may have been underestimating the scale of vacancies.

These figures are, however, only part of the picture. The term ‘vacancy’ is used to describe the number of posts that are not filled by permanent or fixed-term (i.e. substantive) staff. The estimates do not therefore account for either when vacancies are filled by temporary staff or, on the other hand, short-term gaps in staffing rotas caused by, for example, staff sickness.

Using data on the proportion of vacancies that are filled, we estimated that in May 2021 there may have been in the region of 8,000 to 12,000 full-time equivalent nurse and around a further 1,400 doctor ‘real’ staffing gaps due to vacancies alone. While it is good that the majority of vacancies are filled day to day – and that some temporary work may be preferred by the employer and the employee – it is also the case that overuse of agency staff can cause administrative burden, service disruption and additional cost.

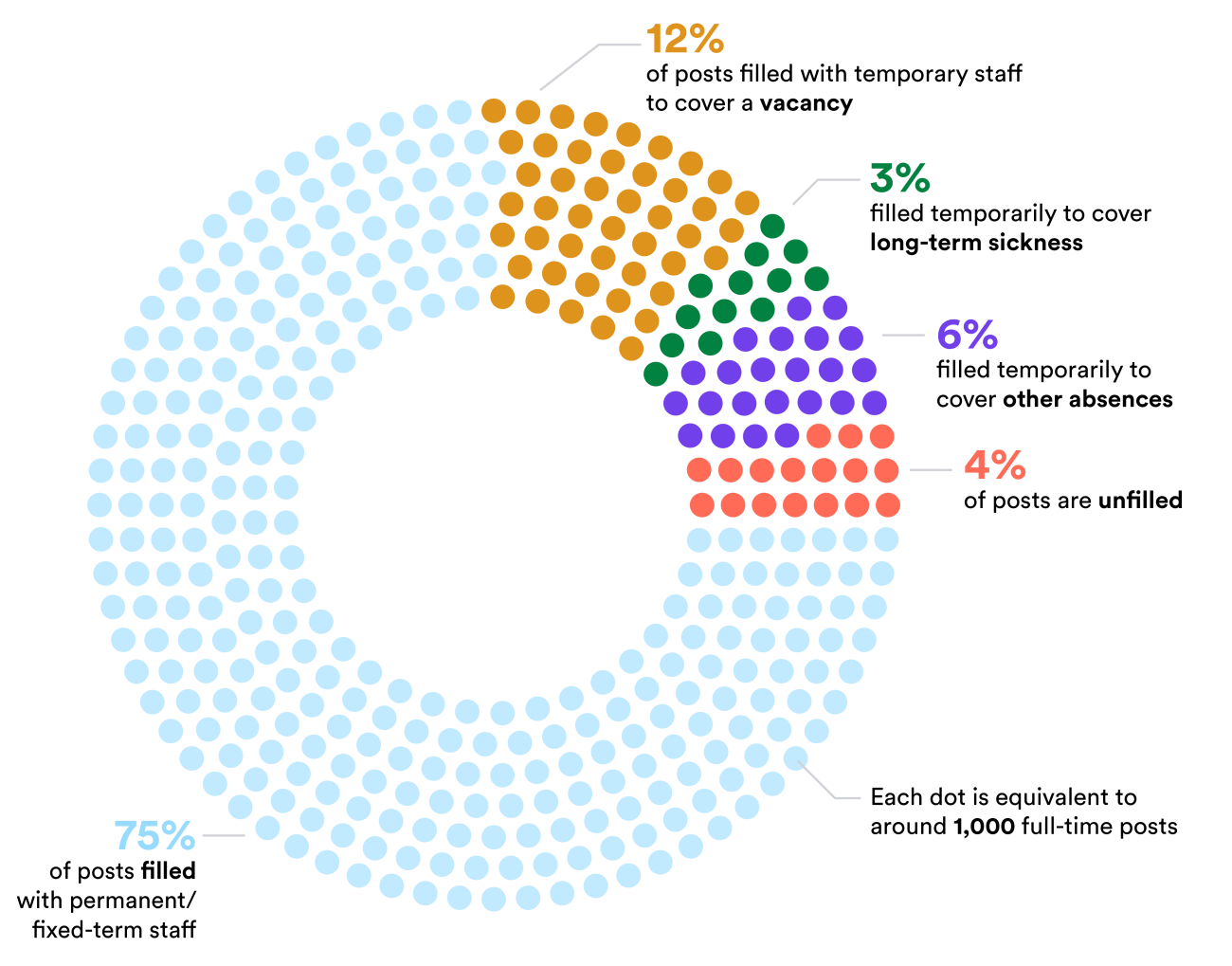

The more detailed data available on nurses and midwives allows us to look at all reasons for staffing gaps – not just failure to recruit to a post (i.e. vacancies). It suggests that only around three-quarters of funded posts were filled with a permanent or fixed-term nurse or midwife (288,900 full-time equivalents), excluding those absent due to, for example, sickness or self-isolation. A fifth were filled with temporary staff (81,700) and the remainder (17,200) were unfilled. The data – from a single day in May 2021 – are not definitive but do give a broad indication of the scale of temporary staff use and unfilled posts.

While the chart below is intended to shed a light on vacancies and staff shortages, many questions remain. Firstly, there is no regularly published data on how many posts are unfilled, with the chart based on data from a single day and it will of course change over time. The current estimates also do not capture, for example, any vacancies across roles that are not directly employed by NHS trusts, including those within contractors or in general practice. The Department and its arm’s-length bodies owe it to NHS staff and patients to have a better grip on the real staff shortfall.