In late May last year, the government announced the launch of the NHS Test and Trace Service, a central part of the coronavirus recovery strategy. It has proved expensive – with reported costs of £11 billion as of last month, and with lifetime costs estimated at £38 billion – and also controversial. With data on the service now covering a full year, I chart the performance of the programme.

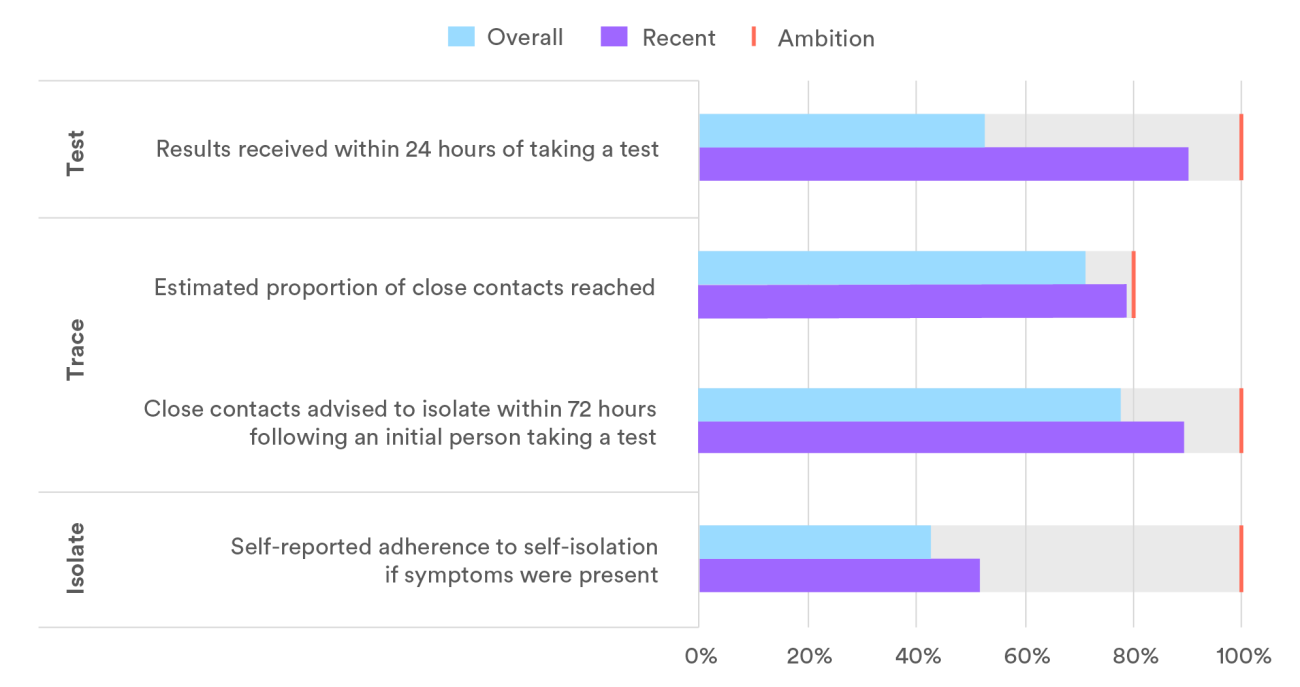

Undoubtedly the Test and Trace service is vast. Over 12 months, it has provided nearly 126 million tests in hospitals, outbreak locations and as part of national swab testing, and reached well over 3 million cases and around 7 million close contacts. It is, of course, unrealistic to expect a perfectly performing programme and our chart shows that recent performance (purple bars) – albeit at a time when there have been relatively few cases and contacts to trace – is higher than the average (blue bars) since it started. However, performance still falls short of ambitions.

At 71%, the estimated proportion of close contacts being reached over the year – a product of 13% of cases and 18% of their contacts not being reached – appears insufficient against the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) advice that an effective system should reach at least 80%, although recent performance is close to the goal. Similarly, the service has failed to live up to its own ambitions for the time taken to advise close contacts to isolate following an initial person developing symptoms (48-72 hours) and to provide test results carried out in person in the community (24 hours).

The chart highlights levels of self-isolation for those with symptoms, which are worryingly low given it is a legal requirement to do so. While alternative data suggest adherence may be higher, failures to self-isolate risk totally undermining the effectiveness of the programme. Our previous paper, co-authored by economic think tank the Resolution Foundation, sets out a costed proposal for removing the key financial barriers and replacing incomes for those self-isolating.

This is not the first critical appraisal of the performance of Test and Trace. We previously noted that the system was far from watertight, with leakages all the way along the pipeline. The government’s own evaluation found that contact tracing was making only a marginal and sub-optimal impact on the levels of transmission. There have also been specific failures, including a failure to plan for increased demand for tests when schools and universities reopened in September, and a data glitch that led to delays in referrals to contact tracers in October may have brought about more than an estimated 125,000 additional Covid-19 infections and over 1,500 deaths. Sadly, that data glitch was not even a one-off.

With restrictions on social contact easing and various variants of concern circulating in the community, we will need to effectively test, trace and isolate cases and their contacts to control outbreaks. After a chequered year, it is clear that Test and Trace will have to up its game.