‘Patient-initiated follow-up’ (or PIFU, for short) is not a new idea and has been referred to in different ways over time, such as open-access appointments, self-managed follow-up, and see-on-symptom appointments.

However, this approach has been given renewed attention given rising waiting times and the backlog of care that built up throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. NHS planning guidance has set the goal of reducing outpatient follow-ups by a minimum of 25% against 2019/20 activity levels by March this year, and moving outpatient attendances to PIFU pathways is viewed as a means to achieving this target.

As the NHS works to scale up PIFU nationally, we explain what this approach is, the problems it’s trying to solve, and what we know so far about how well it works.

What is patient-initiated follow-up?

PIFU is a way of organising care that gives patients and their carers more flexibility over the timing of their follow-up appointments.

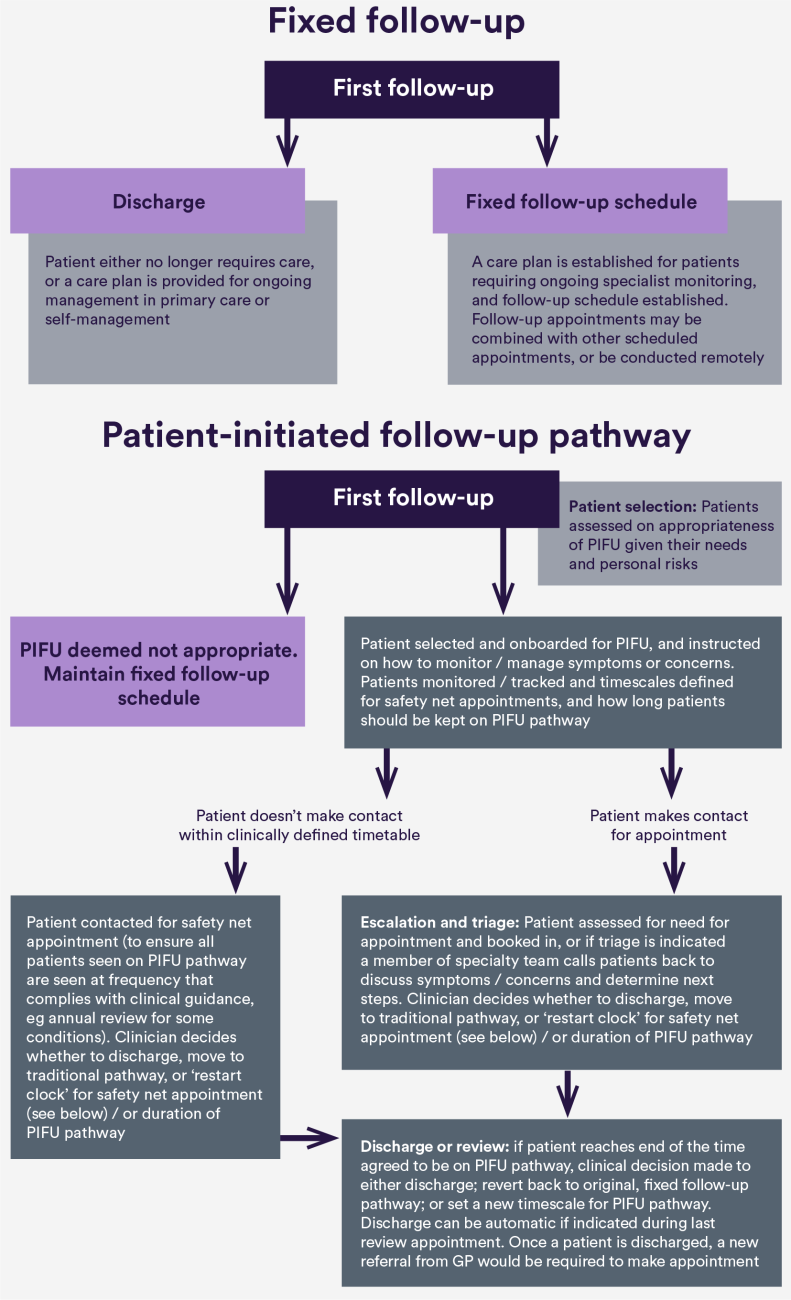

Under traditional care models, patients with chronic conditions or who have had surgery or treatment are typically offered hospital follow-up appointments following a routine, pre-defined or “fixed” schedule (e.g. every three, six or 12 months). Under PIFU, patients or their carers initiate care as and when they need it, rather than being automatically called back for an appointment.

Patient-initiated pathways can take many forms and will require different design and implementation choices depending on a range of factors. For example, a patient-initiated pathway for someone with a chronic symptomatic condition might have very different requirements and considerations than one for a patient requiring follow-up care after surgery. Other considerations will also apply depending on whether a patient has one or more condition, the degree of complexity in their life, and the level of risk associated with a particular condition (e.g. risk of recurrence or disease activity).

What problem is PIFU trying to solve?

One of the key goals of PIFU is to better match clinical resources with patient need – an ever-growing challenge in the NHS as the number of patients waiting for specialist care has been growing.

In England, the total volume of outpatient hospital appointments increased by two-thirds between 2008/2009 and 2019/20 (from 74 million to 125 million a year), with follow-ups accounting for two-thirds of all appointments. This is the largest increase in activity of any hospital service, and long waiting times, delayed appointments and rushed consultations have become increasingly common. With waiting lists for specialist treatment now standing at over 7.6 million (November 2023), the question of how to prioritise clinical time has only grown more urgent.

While there has been a huge growth in the number of outpatient appointments, there are questions over whether they have all been clinically needed. Under current practice, the timing of follow-up care is not necessarily decided by a change in a patient’s condition, or when a patient requires or wants extra support. Conversely, when a patient’s symptoms or circumstances do change, they may experience long waits for an appointment as capacity has been devoted to routine follow-up.

By giving patients more control over the timing of their care, there is hope that PIFU can help reduce unnecessary regular follow-up appointments and the number of missed or cancelled appointments, while freeing up capacity for other patients.

How might PIFU pathways vary?

While all services will likely involve the stages illustrated in the PIFU pathway above (i.e. patient selection and onboarding, escalation and triage, safety net and monitoring, and patient discharge or review), the specific characteristics of services will vary. For example, services might make different choices in:

Patient selection

How patients are selected and the criteria used to determine whether a patient is a good fit for PIFU.

Patient induction (including education, training and support)

- What education and training patients and carers receive before joining the pathway, and what level of self-management support is provided to help people manage their care or know when to contact services.

Patient monitoring and tracking

- Whether and how fluctuations in a patient's symptoms or conditions will be monitored (e.g. patient questionnaires, remote monitoring technology) and how technology might enable this.

Patient communication/ contact with the service

- How patients or carers will contact the service with concerns or questions, and which staff will manage those requests (e.g. nurses, administrative staff).

- Nine studies explored clinical outcomes and all found no statistically significant impact of PIFU.

Escalation, triage and management of clinic capacity

- How clinic slots will be managed and prioritised to ensure capacity for incoming requests.

Safety netting

- How safety nets will work, i.e. how appointments will be triggered and patients contacted if they have not been seen within a reasonable clinical timeframe.

Patient discharge or review

- Which factors will be considered in deciding whether and when a patient should be discharged from the PIFU pathway or go back to fixed appointment schedules.

The choices made within each of these areas will vary for several reasons, including patient preferences, condition, workforce, technological, organisational, and other resource factors (such as availability of additional support or patient hotlines).

What does the published literature say about how well PIFU works, and the impact it has on outpatient activity and patients?

While there is some promising evidence that PIFU might result in fewer overall outpatient appointments compared to fixed appointment schedules, results are mixed across studies.

Our rapid review identified 17 studies published between January 2015 and June 2022 that examined the effects of PIFU on appointment volumes, of which 15 looked directly the effects of PIFU on outpatient activity. Among these, eight showed that PIFU led to a statistically significant reduction in outpatient appointments compared to fixed follow-up, with seven showing no difference between approaches. We also know very little about how PIFU affects overall costs due to a limited number of studies and highly variable results between them.

When it comes to patient outcomes, PIFU appears to have had little or no effect on clinical outcomes or quality of life, but might have a small beneficial impact on patient satisfaction. This suggests that PIFU might be able to reduce the number of outpatient appointments a patient has without any detrimental knock-on effects to quality, safety or experience.

Most studies we rated as low quality, or had variable outcomes. Although most of the PIFU studies were randomised, design issues were still common, meaning that findings are highly context specific. The studies identified in our review involved only eight specialties, and over half (10/17) were conducted in countries outside of the UK, limiting our understanding of how PIFU might work in the NHS context.

More recently published evidence corresponds with our review findings. Two studies published since our review (one with patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer and one with patients with rheumatoid arthritis) found PIFU to result in reduced outpatient appointments compared to fixed follow-up, although the latter involved smartphone application assisted patient-initiated care. Most recently published research on the impact of PIFU on patient outcomes has been conducted in oncology services. While many patients view PIFU positively, evidence indicates that PIFU has little or no impact on outcomes such as quality of life, and some patients have concerns relating to accessing ongoing support and identification of symptoms.

What does our research say about the impact of PIFU?

To address gaps in the evidence, and to understand the impact of PIFU and how it is being implemented in the NHS, the NIHR-funded Rapid Service Evaluation Team conducted a mixed-methods evaluation of PIFU across NHS services in England.

Our new blog and analysis give more details of the evaluation and findings.

The evaluation found the impact of PIFU on outpatient activity varied depending on clinical specialty. For example, for some specialties increasing rates of PIFU were related to less frequent outpatient attendance, but for other specialties the reverse was found. In terms of broader service use, no practically significant association was evident between PIFU rates and frequency of emergency department visits. Staff reported that patients were positive about PIFU as an approach and the support they had received (however, limited data was collected directly from patients themselves through the research). Services implementing PIFU reported limited understanding of its impact on different patient groups, although many acknowledged health inequalities as a key consideration.

Where is more research needed and where might there be risks?

As PIFU continues to be scaled up in England, more research is needed to understand what impact it will have on patients, and whether it will help reduce unnecessary appointments as intended across the NHS.

One major gap in the evidence continues to be whether and how PIFU might affect health inequalities. Most published studies have limited participation to low-risk patients with higher levels of agency to be able to initiate contact – but with few details on how these factors were assessed and determined, and whether results differed by ethnicity, race, sex, gender identity or other factors. It will be important to understand which patients are being selected for PIFU, how their needs are being responded to or escalated, whether they are contacting the service when needed and whether there are any unwarranted differences by patient population.

We also need to better understand what impact PIFU has on other health services, and whether there might be any unintended consequences such as shifting more work to other hospital, primary or community care services. It is unclear from the available published evidence whether any cost savings achieved in studies from reducing outpatient appointments have been outweighed by activity elsewhere, such as educational sessions or increased support from nurse practitioners via patient hotlines. Further research is needed to close these evidence gaps.

This study is funded by the NIHR Health and Social Care Services & Delivery Research programme (RSET Project no. 16/138/17). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The NIHR Rapid Service Evaluation Team (‘RSET’) comprises health service researchers, health economists and other colleagues from University College London, the Nuffield Trust and University of Cambridge who have come together to rapidly evaluate new ways of providing and organising care.