There are some great metaphors around to bring to life the challenge of transforming care while working flat out to deliver current services. Elliott Fisher, architect of US Accountable Care Organisations, talks of ‘remodelling the house while still living inside it’. Don Berwick describes the fear of crossing a crevasse from what we do now to what we will do in future.

Whichever metaphor you use, they capture the idea that most people find change stressful and hard to cope with alongside the pressures of everyday life. Even if there is a clear rationale for making the change – linked to such things as better patient care, and a better working life – it often feels too difficult to take on. While a few visionary leaders thrive on change (and the respect and recognition associated with leading successful invasion), most people are followers.

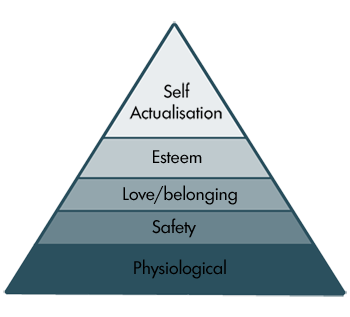

Maslow’s 1943 paper 'A theory of human motivation' described a hierarchy of human needs which influence motivations and behaviours. The general idea is that while several threads of motivation tend to shape peoples’ behaviours at any one time – each feeding different dimensions of personal need and fulfilment – it's harder to address the more complex needs at the top of the hierarchy if the basic survival needs are unmet.

Maslow's Hierarchy of needs

Could Maslow’s theory help us to understand the world of jobbing GPs? As the day-to-day pressures of delivering care and balancing the books increase, they are more likely to focus on their ‘safety’ needs – on keeping their job, their income and their health – than how to gain peer approval and status through cutting edge innovation and change.

The irony is that change may be the only way to preserve jobs, but not everybody is a strategic thinker and most of my colleagues are too busy delivering care to focus on that knotty conundrum.

And this issue is not just confined to GPs. The problems of change overload and change fatigue are well rehearsed in the wider NHS. Earlier in the year, Sir Stuart Rose’s review of NHS leadership argued that: ‘The level and pace of change in the NHS remains unsustainably high: this places significant, often competing demands on all levels of its leadership and management. The administrative, bureaucratic and regulatory burden is fast becoming insupportable.’

As those at the top of NHS England and Department of Health weave their policy web, set out budgets, and work through the Personal Medical Services (PMS) contract review, it is worth keeping Maslow in mind. If staff are focused on the basic 'safety' elements of protecting income and meeting family needs, their capacity to engage with higher level motivators will reduce. The likelihood of engaging thousands of GPs in ‘remodelling the house’ reduces if day-to-day survival in the house requires more and more effort.

So what would improve awareness among policy makers and planners of the psychological factors that shape workforce behaviours? A number of organisations now have an artist in residence, whose task is to see their world differently. The science museum, for example, says of its Artist in Residence Programme: ‘Over the years, the museum’s artists in residence have created a variety of… works that see science in a different way from mainstream visitors’.

Is it time for the NHS to get a psychologist in residence? Achieving the level change required to implement new models of care will stretch even the most resilient ‘self-actualising’ leaders. What would a psychologist say about how followers might react to extra demands, more KPIs and local incentive schemes in an austerity PMS contract?

I use the lead time for organising a meeting about transformation in my local area as a barometer for people’s motivation and willingness to engage. It is often four to six weeks. If people were really motivated and enthusiastic, the suggestion of a breakfast meeting next week might not seem so laughable. In reality, paper work, extended hours, weekend opening, school plays, dinner with one’s spouse and perhaps even the odd hobby, too often trump the re-modelling work.

If transformation and new models of care are our best hope for the future, then we neglect the drivers of personal and professional motivation at our peril. Returning to Elliot Fisher’s metaphor, if we fill the current house with too much day to day clutter, creating the right conditions for a rebuild becomes that much harder.

Dr Rebecca Rosen is a Senior Fellow in Health Policy at the Nuffield Trust, a GP in Greenwich, South London and a board member of Greenwich CCG.