There is an eye-catching deal on the table.

Broadly speaking, it would inject 3.4% more into NHS consultants’ earnings, alongside a reshaped pay package that would reinvest money into basic salaries that would otherwise have been spent on new locally agreed clinical excellence awards. Under the new deal, basic salaries (earnings before overtime, awards, geographical payments or premia) would increase overall by 4.95%. It also proposes changes to pay progression and the pay-setting process.

“If money go before, all ways do lie open”

The deal stands over and above the existing 6% pay uplift (before adjusting for inflation) for this financial year. The nature of the investment, which would change the pay scales and decrease the number of years in post until consultants reach the maximum basic salary, means that the effect is uneven, leaving basic salary levels as at March 2024 between 6% and 20% higher than a year before, equating to increases of between around £6,000 and £19,000. Factoring in pay progression the increase is higher still, with those who started the year with 12 years of service as a consultant seeing a £25,968 (24%) rise in their basic salary level. The non-uniform nature of the increase has frustrated some newer consultants who point to their increases being lower in value; senior colleagues keeping lucrative pre-standing clinical excellence awards (which are no longer being offered); and their less advantageous pension arrangements.

All in, this means that a full-time consultant’s average basic salary level as at March 2024 would appear to be around an estimated £117,300, while average total NHS earnings could be equivalent to around £147,900 a year. The deal would have an upfront cost to the public purse equating to somewhere in the region of £450 million a year, although some of this will be returned to HM Treasury through income and other employment-related taxes. Unless this is fully funded with additional investment to the NHS, savings will have to be made elsewhere which could have negative consequences.

“Beware the ides of March”

This recently announced deal would come into force in January 2024, only a couple of months before the pay review body is expected to make recommendations for the pay level for 2024/25. In fact, much rides on the decisions due in March. To explain why, consider these two hypothetical scenarios to help frame this deal:

- Although it is highly unlikely, the pay review body could conceivably make no further increase in 2024/25 if they considered that the rise this deal confers is already adequate to ensure sufficient rates of recruitment and retention in the consultant workforce in the coming year. In this purely theoretical scenario, the deal would equate to an average £1,400 one-off bonus in 2023/24 (because of the deal being brought forward to January), and a 3.4% average pay increase over the levels the body recommended for this year, which would likely be around (or potentially a bit above) inflation.

- Conversely – and this is seemingly what the BMA and government’s wording suggests – the pay review body (who are short of evidence on what absolute pay level is required to achieve necessary levels of recruitment and retention) could work from this new higher baseline. In such a scenario, the deal equates to a 9.4% pay increase on average in 2023/24, albeit with a staggered implementation with the full amount only applicable from January 2024.

The first scenario would be unpalatable for many in the consultant community, whereas the second scenario will cause unrest for other groups, including NHS nurses, midwives, allied health professions and health care scientists who got a 5% increase for 2023/24. Doctors other than consultants may also look at this deal with envy. Either way, the pay announcements in March will be a focal point for the industrial relations.

“Nurse, give leave awhile, We must talk in secret”

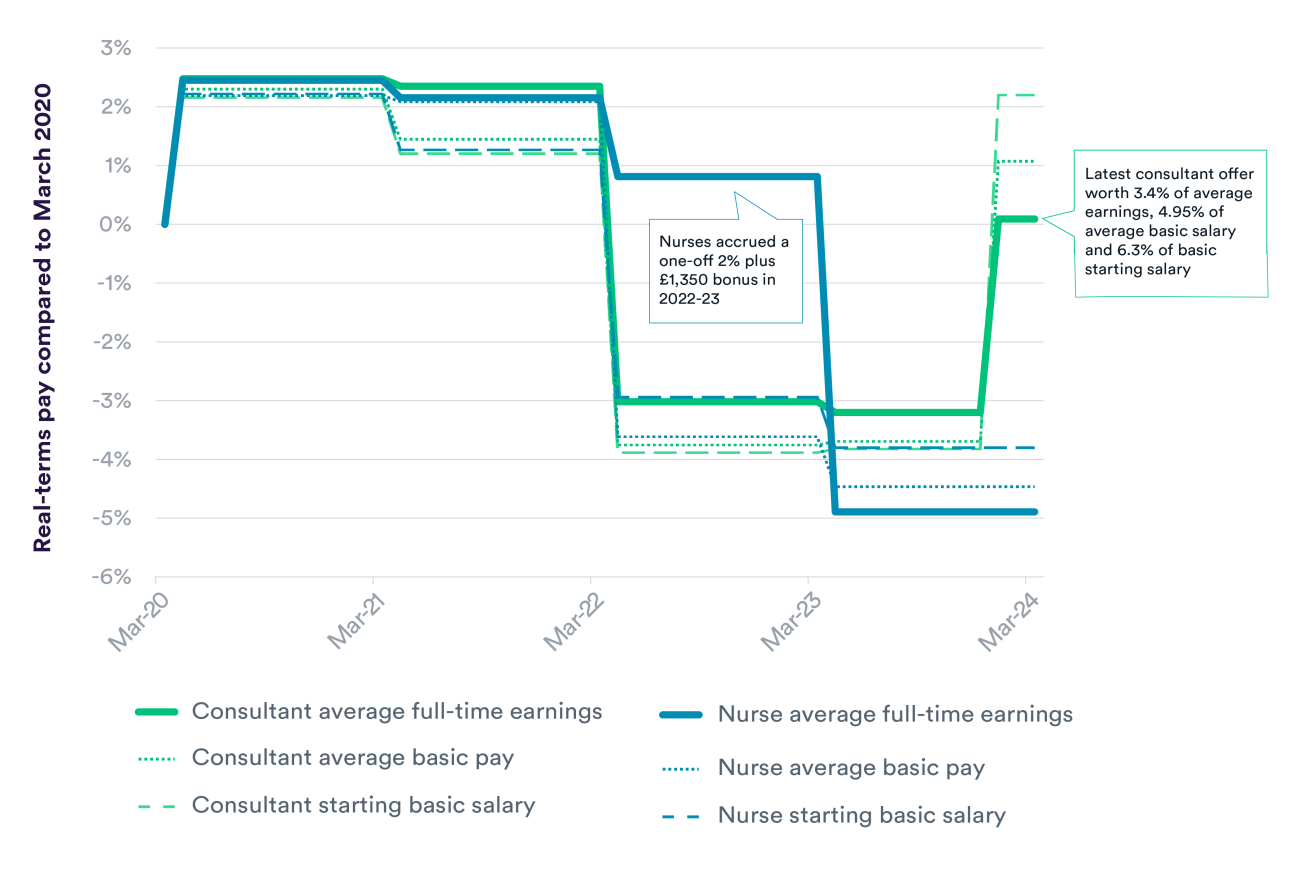

The announcements of this enhanced offer to consultants instantly sparked outrage from the Royal College of Nursing. The earlier deal for nurses (and the majority of other NHS staff) was particularly complex – discussed here. But seeing how their deal stacks up against this one may be a bitter pill to swallow, even though they benefitted – unlike consultants – from one-off bonuses accrued in 2022/23. In effect, compared to the start of the pandemic, nurses’ average earnings as at March 2024 will have likely fallen about 5 percentage points in real terms, whereas consultants’ earnings would have – over this period at least – caught up with inflation (see chart below). The government has tried to divert from this by noting that this consultant deal is not revisiting the 2023/24 offer, but this is a tricky line to justify given that it would increase pay in this year and create a higher baseline in 2023/24 for future deals to be based upon.

As we have previously recommended, given the move towards multi-disciplinary teams and changing skill mix, further consideration should be given to the relative pay of different staff groups. Only South Korea appears to have a higher pay difference between specialist doctors and nurses (3.7 times more) than England (3.3 times higher). The average across the 26 countries with broadly comparable data is specialist doctors earning 2.3 times more than nurses. As at March 2024, the average annual NHS earnings level of consultants would be around £103,000 higher than nurses.

“Things won are done”

The package was announced alongside some renewed expectations about how the contract will be managed differently. In particular, there is an expectation that consultants will have to more clearly demonstrate skills, competencies and experiences to receive pay progression. However, such management has proved difficult in the past. A previous survey (albeit somewhat dated) found that less than a third of trusts stated that pay progression for all or most consultants either depended on achieving objectives set out in job plans or achieving objectives from appraisals.

A surprising omission from the fine-print of the new deal is any detail around how the NHS should secure additional activity from consultants. When the consultant contract was introduced two decades ago, consultants wishing to work an extra block of activity in private practice were expected to first offer it to the NHS, at standard contractual rates. But this principle has been difficult to uphold: a previous survey found that only one in eight NHS employers actually had accurate information on how much private practice work all their consultants were doing. The new deal appears to be a missed opportunity to grapple with this, which could prove an oversight given the need to boost activity to address the backlog.

However, the deal does expand the definition of so-called supporting professional activities (i.e. not direct clinical care) to include supporting NHS priorities such as the elective recovery and the delivery of the NHS long-term workforce plan. Undoubtedly, delivering the hugely ambitious increases in training and education signalled by the workforce plan will require greater input from consultants (including non-clinical work), but for any real benefit to be realised from this definitional change there will likely need to be a material improvement in the consultant job planning process.

Some other reforms to the contract – such as offering shared parental leave in line with other NHS staff – are perhaps overdue and welcome given the need to promote retention of those with parental responsibilities. Similarly, the reinvestment of money from clinical excellence awards towards basic pay could – alongside the changes to the pay progression framework – go some way to reducing gender pay inequalities.

“Strong reasons make strong actions”

The deal also incorporates commitments to change the pay review process. Ensuring that the process is more timely and is supported by better data and evidence seem positive steps to making the pay-setting arrangement fit for purpose. However, we would like to see the government go further in these reforms, including on the scope to have longer-term deals with force majeure clauses whereby they are reviewed if economic or service conditions fall outside set parameters.

And bold actions should not stop at the pay review process. The evidence is clear that increased pay alone is not sufficient to maintain staff retention and does not compensate for poor working conditions. We can hope that this deal contributes to an improvement in the industrial relations but, to quote the famous Bard one last time, “some consequence yet hanging in the stars”.