Over the nearly 30 years of direct rule in Northern Ireland, reform and modernisation in public policy was virtually non-existent. Other matters of course dominated, with British ministers preoccupied with security and economic issues. The lack of any real reform was generally viewed as a temporary stop-gap until devolution was restored.

Shortly after the devolved structures were established, it became apparent that the health and social care system – with an annual spend accounting for almost half of all the devolved Government’s spending – was struggling to meet the demands and expectations of a growing and ageing population. It was clear that health and social care was one of the most challenging issues for the new executive.

The diagnosis is clear

Since the turn of the century, this relative neglect has been addressed by a series of seven systematic reviews and assessments of Northern Ireland’s health and care system.

At a broad level, these reviews reached similar conclusions about the problems the care system faced and the range of solutions needed to improve things. The diagnosis was that radical transformation was required to ensure a service that was efficient, effective and equipped to meet the needs of the 21st century.

Reviews of the Northern Irish health and social care system

2001: The Acute Hospitals Review

Led by former civil servant Maurice Hayes, this recommended reducing the number of hospitals, amalgamating commissioning boards into one, and integrating health and social care.

2002: Developing Better Services

This blueprint for services laid out plans to reduce the number of hospitals, and improve working between different services.

2005: Independent Review of Health and Social Care Services in Northern Ireland

Led by John Appleby, this review found that the Northern Irish NHS lacked ways to manage and incentivise better performance.

2011: Rapid review of Northern Ireland Health and Social Care funding needs and the productivity challenge 2011/12-2014/15

Led again by John Appleby, this review of finances and efficiency found that the health service in Northern Ireland needed significant additional funding, but also had considerable room to improve productivity.

2011: Transforming your care

This major review concluded that the current system was not fit for purpose and there was an unassailable case for change. It identified a mismatch between the need for a proactive model based on prevention and the needs of patients, and the reality of a system focused on hospital care. The report called for a major shift in the design of services, making 99 recommendations.

2014: The right time, the right place

Former English Chief Medical Officer Sir Liam Donaldson led this review of governance in the Northern Irish service. It called for more flexibility and room for innovation, a reduction in the number of hospitals, and better responsiveness to patients. The review expressed concern that the vision set out in Transforming your care was not being implemented.

2016: Systems not structures – Changing health and social care

A panel led by Professor Rafael Bengoa – an internationally experienced former health minister of the Spanish Basque Country – called for the development of an accountable care system that aimed to manage people’s health and keep them well. It concluded that the system had the capability to deliver on key objectives, but stressed that realistically this would be a long-term 10-year plan.

In the light of these reviews and reports, there appears to be considerable consensus across health and social care about what is required to deliver the necessary reform and the consequences of maintaining the status quo.

What is much less clear is how to achieve this. There is a difficult backdrop: austerity, increasing demand, rising expectations, and political uncertainty.

Political leaders show an unwillingness to move away from short-term parish-pump politics to long-term processes that deliver better outcomes.

It is not clear that the public are in a position to call for change. They may not have good information about how well the service meets their needs, and have not necessarily been made part of the long conversations about change, which as a result can sound like it brings bad news.

Patients pay the price for the status quo

But the impact on patients of the current impasse in implementing necessary changes is stark. In June this year, for example, one in six of the entire Northern Ireland population was on an outpatient or inpatient waiting list. In England the figure is one in 14.

And over 64,000 people had been waiting over a year for their first outpatient appointment – a quarter of all those on the waiting list. In England, by contrast, around 1,500 people were still waiting over a year – just 2 per cent of the number in Northern Ireland for a population over 30 times larger.

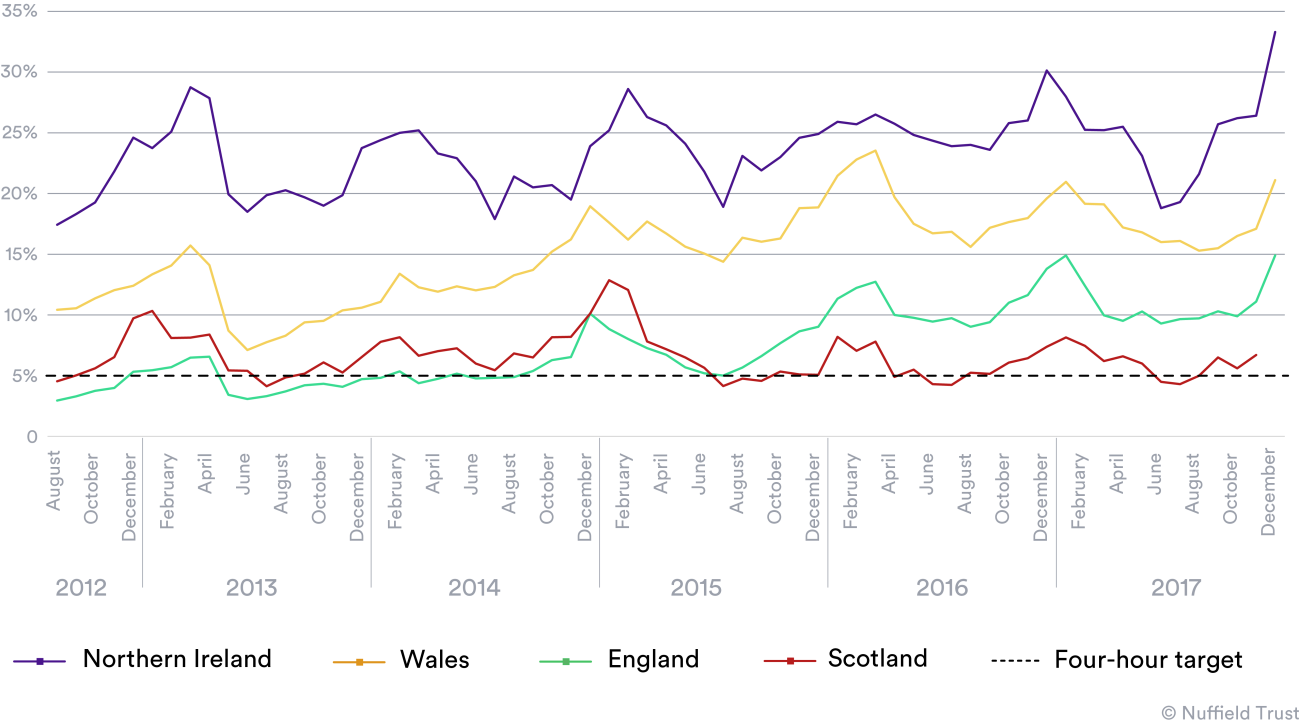

And in accident and emergency departments, patients in Northern Ireland have for many years had to put up with the longest waiting times of any part of the UK (see chart below).

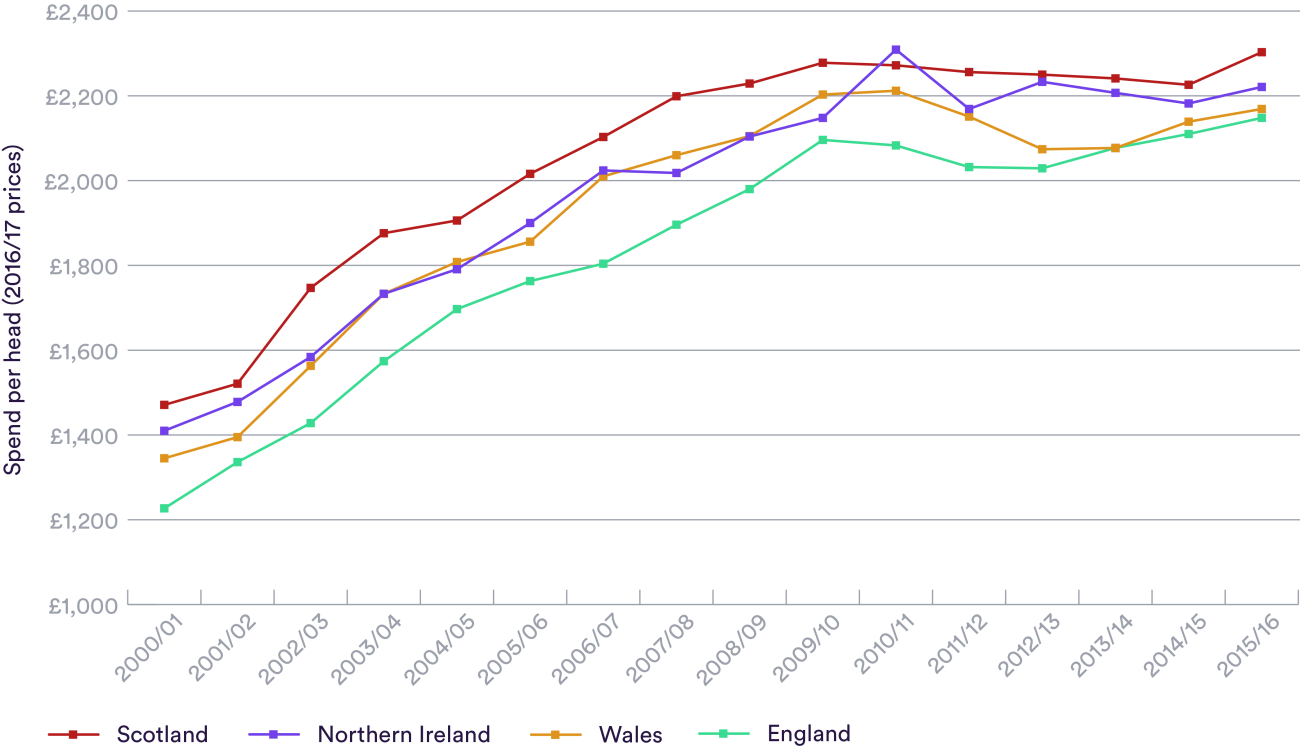

It could be argued (and indeed it has been) that the solution is more funding. More money is always welcome in any health service, but Northern Ireland’s spending has increased by nearly 60 per cent per head of population in real terms since the turn of the century.

It has also consistently spent more per head than England, yet continues to achieve less for patients (see chart below). Although studies suggest Northern Ireland’s higher spending may be partly justified by greater health care needs, it seems unarguable that the performance gap far outweighs the funding level.

And as all the reviews of Northern Ireland’s health and care services have concluded, it’s not just the size of the budgets that matter – it’s how they’re spent.

Where are we now?

The latest of these reviews in 2016, chaired by Professor Rafael Bengoa, was widely accepted across the political spectrum in Northern Ireland and it appeared that change would be delivered.

For now (and once again), that hope has been dashed.

Following the Assembly elections in 2016, the new Government led by Sinn Fein and the DUP stressed their willingness to work for Northern Ireland and deliver on key issues such as health and education. But by January 2017, as a result of the renewable energy heating scandal, the coalition collapsed.

Without political leadership, the system reverts to no more than keeping the show on the road, with important reform decisions mothballed. Once more the opportunity cost of political failures at the top of the system can be measured in further delays in grappling with long overdue reform – and a continuation of unnecessarily poor services for patients.

Northern Ireland’s NHS has an enviably thorough blueprint for action – and a lot of catching up to do. The public should not put up with further delays.

Suggested citation

Heenan, D. Appleby, J. (2017) "Health and social care in Northern Ireland: Critical care?" Nuffield Trust comment www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/health-and-social-care-in-northern-ireland-critical-care