Across the UK, the dynamics of social care governance are complex, split between the national and local. While central governments set policy and allocate some funding, it is local governments in England, Scotland and Wales, and health and social care trusts in Northern Ireland, which are responsible for understanding the needs of their local populations and to commission suitable services to match.

However, the current state of social care systems across the UK suggests current arrangements aren’t working. Current reform plans differ between the UK’s four countries, but one common theme is that they all, to varying extents, propose a strengthening of the role of national government in the governance of social care.

In this blog – which accompanies the final suite of explainers in our updated series about social care in each country of the UK – we consider the extent to which the four UK countries are moving towards greater national oversight, and whether these shifts are likely to make a difference to the experience of people who draw on care and support.

How are the UK countries increasing the role of national government?

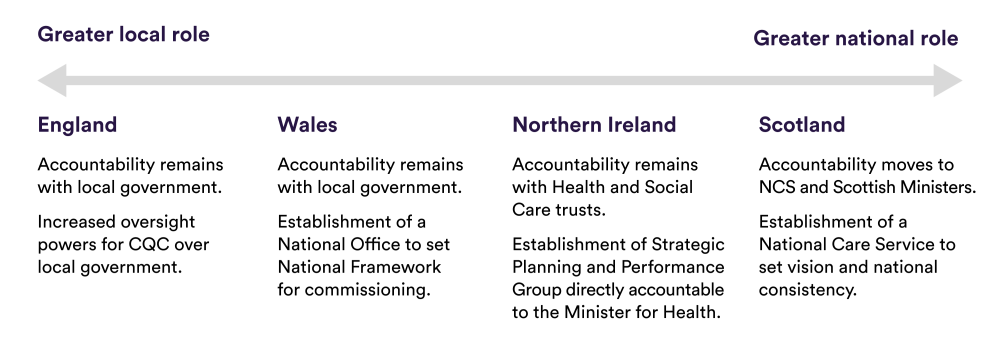

The diagram below represents where countries might sit along a continuum of local/national government responsibility, should their reforms be enacted as planned.

Under plans in England and Wales, local government will remain at the heart of social care commissioning, delivery and funding. But local authorities in England will soon be held to greater account with the introduction of the local authority assurance framework, through which the Care Quality Commission will assess how well they are performing their statutory duties. And while the national grant allocated to local authorities remains unringfenced, which leaves local authorities to decide how to spend it, there have been a number of additional one-off grants recently awarded to councils which come with conditions.

The funding announced at the Autumn Statement to speed up hospital discharge, for instance, requires local authorities to provide fortnightly activity reports to central government. Similarly, the funding diverted from charging reforms will mandate local authorities to fund improvements across priority areas (capacity, sustainability, waiting times, and workforce) and evidence these through progress reports. Greater oversight and reporting requirements may incentivise improvements in some English local authorities, but with budgets continuing to be squeezed as a result of inflation and winter pressures, some question whether these requirements may just be setting up local authorities to fail.

Wales is taking things one step further in being more directive, with the establishment of a national office to pool good practice around local authority commissioning. It is hoped that more national approaches within Wales, for instance to fee setting, can avoid unnecessary duplication and create more consistency across the country as a result. While there is potential to foster more national direction around what ‘good’ looks like for local authorities, stakeholders have concerns that the establishment of another national institution may create an additional layer of unnecessary administration.

In Northern Ireland, the Health and Social Care Board, which was previously responsible for setting commissioning priorities for health and social care, has been replaced by the Strategic Planning and Performance Group directly accountable to the Minister for Health. This direct ministerial oversight of health and care planning is intended to reduce bureaucracy. But with political turmoil meaning there is currently no Health Minister, there may be some risks to having health and care planning so close to national politics.

Scotland has been the most radical, with legislation last year to remove responsibility for social care from local government and place it with a newly formed National Care Service and Scottish ministers. Extensive reviews have concluded that changes are required at a national level to address the chronic issues the Scottish system currently faces. It is hoped that the increased accountability that ministers hold through the National Care Service can provide an impetus to address these challenges and ensure consistency across the country. These plans have not been universally welcomed, however, with some calling the National Care Service a “power grab“ from the centre that risks losing local proximity to people and their communities.

National or local: what’s best?

We recently brought together policy-makers, commissioners and providers from across the UK to discuss what we can learn from each of the four countries as they undergo reform. We heard consensus from our attendees that there could be significant potential in having greater national level oversight for the ‘big ticket’ items: setting a clear vision; providing stable and sustainable funding to achieve this; pooling and sharing knowledge and good practice; and improving conditions for the workforce.

National leadership is also needed for urgent crises, as the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted, and is now needed more than ever, with winter, cost-of-living and other financial pressures piling on.

But if it is encouraging to see national governments across the four countries taking the problems facing their social care systems seriously, our stakeholders were also in agreement that the heart of social care planning and delivery must remain local. Social care is fundamentally about people and the communities they live in. Sufficient autonomy and flexibility are needed at local level to adapt to circumstances and varying requirements, to make sure that services meet the current and future needs of those the system is intended to serve.

Successfully balancing the local and the national – bringing the benefits of efficiency and appropriate consistency of a national approach, while enabling the flexibility and appropriate variation that must happen at a local level – should be a guiding principle of any future reform. Getting that balance right will be crucial if the social care system is to bring about meaningful improvement to people’s lives as well as weather storms ahead.

Suggested citation

Oung C (2023) “Local or national: what role should the government play in social care?”. Nuffield Trust blog