From time to time, I am asked to look at what we have learned about health policy-making – often by people outside the UK who wonder at the amazing laboratory of reform we have been operating – and also at our apparent inability to complete most of the experiments or to learn from them.

I am often struck in my dealings with other health systems by how much more they are capable of taking a long historical view of the evolution of policy, and the lessons that can be drawn from this.

So my team have prevailed on me to try and codify some of the learning we have about the English policy formation and implementation process, and to reflect on what could be different.

It would be very easy to focus just on the failures, but there are policies that were done well and had their intended effect. I asked for suggestions from my Twitter followers. Unsurprisingly, as inhabitants of the same bubble, they came up with a similar list to me:

- NICE

- National service frameworks

- Reduction in health care acquired infections

- Improvements in infant and child mortality outcomes in Scotland

- Smoking ban in public places

- Sure Start

- Reductions in teenage pregnancy

There were also nominations for more micro initiatives:

- Stroke centralisation

- Daily ward rounding.

It's notable that:

- Most of these are relatively focused

- They all had a pretty good evidence base and, where they didn’t, there was some good theory

- While their implementation may have been difficult in some cases, none of them are particularly complex pieces of policy design.

Also, very few of the examples were from the last 10 years.

The list of policy disappointments and disasters that people shared have almost the opposite characteristics:

- 2012 NHS Act – the Lansley Reforms

- PFI

- NPFiT

- Transforming Community Services

- Modernising Medical Careers

These were also the enthusiasms of policy entrepreneurs – quite a few also have acronyms. Perhaps that signifies something.

Also: closeness to an issue is likely to make you more aware just what a mess it was:

- Dentists – dental contract

- Thyroid patients – medicines policy

- Junior docs – MMC

- Some GPs – the ‘attack on partnership'

- Nurses – abolishing the bursary

The most disappointing were perhaps the things that were not done

- Social care funding reform

- Workforce planning

Let’s explore what goes wrong – first with the design of the policy, then with the implementation. Think about why this happens and think about what we could do about it without rewiring our entire political system.

Policy design

Models and theories

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist”

The theory of policy-making as a purely rational process has long been superseded by theories that acknowledge ‘bounded rationality’, in which some options are not considered and policy-makers will satisfice rather than optimise or maximise.

The Lansley reforms exemplify this, being to a large extent based on a theoretical model drawn from the economics and policies of the privatisation of utilities.

While all models are flawed, some can be useful. It is dangerous when the model relies on theories and evidence that have been oversimplified, distorted or are just wrong. Or when they rely on a particular context, for example: Lansley designed his reforms in a period of plenty and implemented them in austerity – he made no attempts to change them.

Context and history

So context, and therefore history, matter. There is a reason why path dependency is a powerful driver of policy ideas and direction. Having due regard for this is one of the reasons why the 20-year project of reform in the Dutch health system seems to have been so relatively successful.

“People make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past ”

The neglect of context and history often leads to bad ideas being resuscitated or borrowed from elsewhere and applied in situations in which they are unlikely to work. It’s also worth checking that the ideas being borrowed actually work as their proponents claim.

Policy-makers in large systems have a problem because of wide variations in the starting points of local systems. They sometimes find it convenient to ignore this and create cookie-cutter policy that works ‘on average’ and therefore, has a poor fit in places that are not average – i.e. most of them.

Poor conceptualisation

Some poor design emerges from a failure to really understand the nature of the problem or how the problem interacts with the system. Common issues here include:

- Faulty logic and theories about causality – it’s not uncommon to see logic models in which the connection between the actions and the results are not really supported by evidence.

- Conceptualising problems as being about a failure of incentives, structures or rules when they are likely to be more about culture, behaviour and relationships – and therefore some way out of the reach of most policy instruments.

- Assuming that the recipients of the policy will respond in the way that you intended. They may be rational actors but could have different ways of evaluating the signals produced by the policy. Or they could be optimising / satisficing in ways that are different from those you assume; or they may be getting so many imperatives, market signals or other pressures that some policies are simply ignored, subverted or watered down.

- A tempting response to the problems of complexity, context dependence, heterogeneity and other problems is to simplify the issue – but this means that many of the subtle qualifications and conditions required to make the idea valid are lost.

- One way of simplifying – and a particular hazard – is the use of the personal experiences of the policy-makers as a guide to the other 60 million users of the system. E.g. the way that primary care policy has so often been based on the access requirements of middle-aged commuters to SW1.

- Even worse is the temptation to design the policy for an atypical subset (good or bad) because these are front of mind for policy-makers. For example, the 2004 consultant contract – which seem to assume that those consultants who were not doing private practice were playing golf.

A related issue is the attempt by policy-makers to frame an issue in a way that is helpful to their argument – for example, ‘we need to rationalise hospitals because of issues of safety or critical mass’.

The problem here is often that:

1) the evidence behind the framing is contested

2) other stakeholders have a different way of thinking about the issue and different criteria for determining what the trade-offs are – e.g. valuing short travel times; and

3) stakeholders may simply not believe the account they are given.

Too many or unclear objectives

Policy-making theory recognises the problems of trade-offs between objectives, but there is a particular issue where policies are created with more objectives than they can sustain or which generate tensions. Among other things, Lansley’s reforms aimed to reduce bureaucracy while creating a very large volume of transactions.

Mission creep and ‘Christmas tree’ policy-making, in which additional objectives are loaded onto the policy, can happen at any point in the development process.

This is a particular feature where there is internal competition between policy leads. These policy entrepreneurs will try to grab the opportunity of attaching their policy goal to an instrument that is fashionable or gaining traction.

The ambition of many civil servants who had policy responsibility for specific disease areas was to get an incentive relating to the management of that disease into the Quality and Outcomes Framework, the CQUIN and so on.

Having so many competing objectives has bedevilled the search for the right size for commissioning organisations. Too small and they cannot manage risk, lack expertise, have high costs and do not have leverage with hospitals. Make them too large and they cannot engage with primary care very well.

Poor design process

In 2002, the then Secretary of State Alan Milburn announced “radical plans to allow the private sector, charities and universities to take over management of England's failing hospitals”. The idea was called franchising – borrowed from the commercial sector. This illustrates three interesting design problems.

- Retrofit – the policy idea was announced before it had been worked out. Unhelpfully, Milburn added enough detail to the idea that it constrained the policy-makers’ ability to turn it into something sensible.

- Cargo-cult policy – the idea was borrowed, but without a clear understanding of what it really meant, so the outward appearance of the idea was replicated but the actual active ingredients that made the policy effective in, for example, McDonalds was not.

- Solutions looking for problems – it was by no means clear that the reason for the problems that the hospitals were having were related to the quality of its existing management. The evidence that simply changing the management team improves performance is not encouraging.

Another element of a poor design process that is far too common, and was a major feature of the Lansley debacle, is failing to elicit or listen to feedback – particularly from wider stakeholders outside or beyond the usual suspects or people you can guarantee will agree.

This failing is often associated with selective use of the evidence and ignoring findings that do not support the direction – called policy-based evidence. Sometimes, as in the assumption that out-of-hospital care is always cheaper than care in hospital, this seems to be based on wishful thinking or on a failure to understand the context in which the decision is being made.

This type of group think is exacerbated by a lack of serious scrutiny. It is identified as a major contributor to other failures by King and Crewe in their survey of a large number of UK government blunders. Amusingly, but probably with some justification, they point to the problem of scrutiny by PowerPoint that tends to over-simplify, obscure issues and risk, and even to brainwash.

“Power corrupts. PowerPoint corrupts absolutely.”

The most obvious recurrent design problem stems from the short time horizon of ministers and their need for rapid results. The electoral cycle is a problem in many countries but ministers often come and go even faster here, which incentivises speed over careful design and engaging with the messy realities. The political will necessary to drive long-term policy-making also tends to dissipate over time.

Implementation

The good news is that quite a lot of policy does manage to avoid the design problems I have mentioned. However, there are a range of hazards that occur between designing a good policy and implementing it. The more ‘transformational’ it is, the more likely that these will create failure.

Perhaps the most significant issue for complex transformation programmes in many health systems is the lack of a strong narrative that is well articulated in a compelling way. Andrew Lansley was more honest than most:

“I am sorry if what I am setting out to do has not communicated itself”

If you are relying on a complex multi-layered policy to explain itself without any assistance, you are already lost. A failure to communicate the benefits, the case for change and what needs to be done is quite common.

While intellectually and in terms of coherence and practicality, miles ahead of Lansley, the Five Year Forward View and the Long Term Plan both suffer from the problem of being highly technocratic. They have long lists of deliverables and conceptual ideas about integration, but do not appear to have a clear theory of change. This is a common issue with health policy in many countries – are we relying on professionalism and intrinsic motivation, managerial command and control, the invisible hand of the market or telepathy?

Other areas to highlight resonate with much that is already in the business literature:

- Poor process and unclear leadership

- Timescale – policy-makers are very prone to optimism bias. Complex change requires continual negotiation and often takes place in unpredictable ways and at varying speeds. People need to build new relationships and establish different ways of working. The logistics of getting clinical staff together are challenging and these practical issues are often not really understood. There is little that can be done to compress the time that is needed for these tasks.

- The most extreme version of this is failing to understand the difference between issuing the policy and having it implemented – I overheard this exchange in about 2006:

Prime minister’s advisor:

“We’ve got payment by results, we’ve got competition and GP commissioning, we just need to let it rip.”

Secretary of State’s advisor:

“No, we’ve just said we’ve got them, that’s not the same thing.”

I am afraid the list goes on:

- Insufficient resources especially for double running, organisational development and change management.

- Not enough attention to workforce, capital, IT or other infrastructure requirements.

- Payment systems and regulatory machinery that are misaligned – a particular issue where DRG-based funding is used in systems trying to reduce hospital admissions.

- More policies and procedures being issued on top of a multiplicity of existing policies and procedures.

- Pilot projects that are hard to convert into sustainable change.

- Unintended consequences that are unhelpfully powerful and unexpected.

- Superficial attempts to change deep culture.

One element of this deep culture that receives relatively little attention is the impact of having a large and powerful workforce with views and values that are often not aligned with those of management.

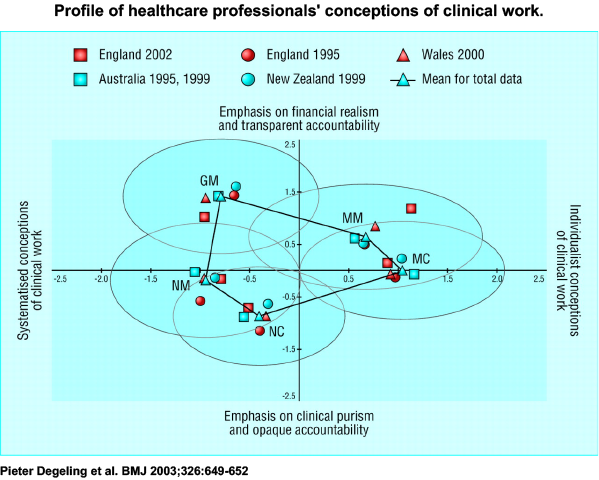

Pieter Degeling’s work measuring the attitudes of nurses, doctors and managers found similar divergence on key dimensions in different countries (although China was different).

- Autonomy vs accountability

- Responsibility for resource use vs clinical purists who are not comfortable with the idea that clinical decisions have financial implications

- Attitudes to team working and power

- Willingness to adopt systemised work processes.

All three groups were in different places from each other, with clinical managers often stranded in a no man’s land between them.

His more recent unpublished work suggests that new generations of clinicians and managers are closer together, but there are still differences that matter. Clinical leadership is often vital for the implementation of many policies, but simply co-opting clinical leaders to sell a management message can backfire.

Complexity, velocity and scale

There are a number of factors acting on the system that mean that these problems are not easy to solve.

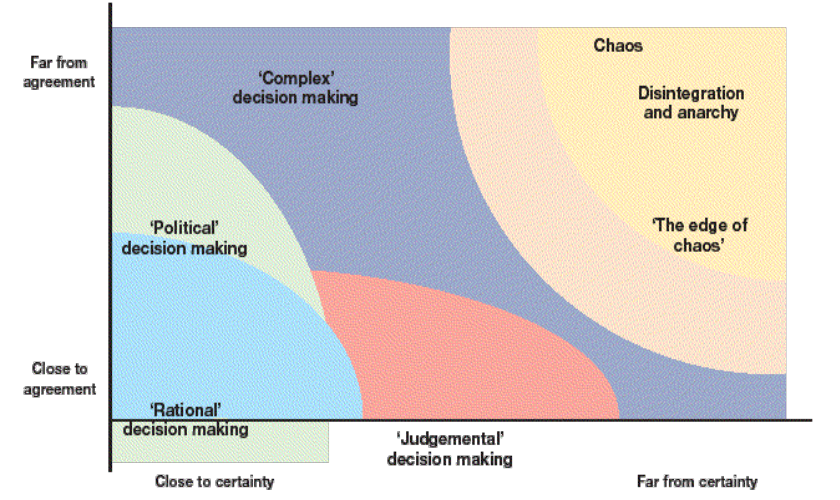

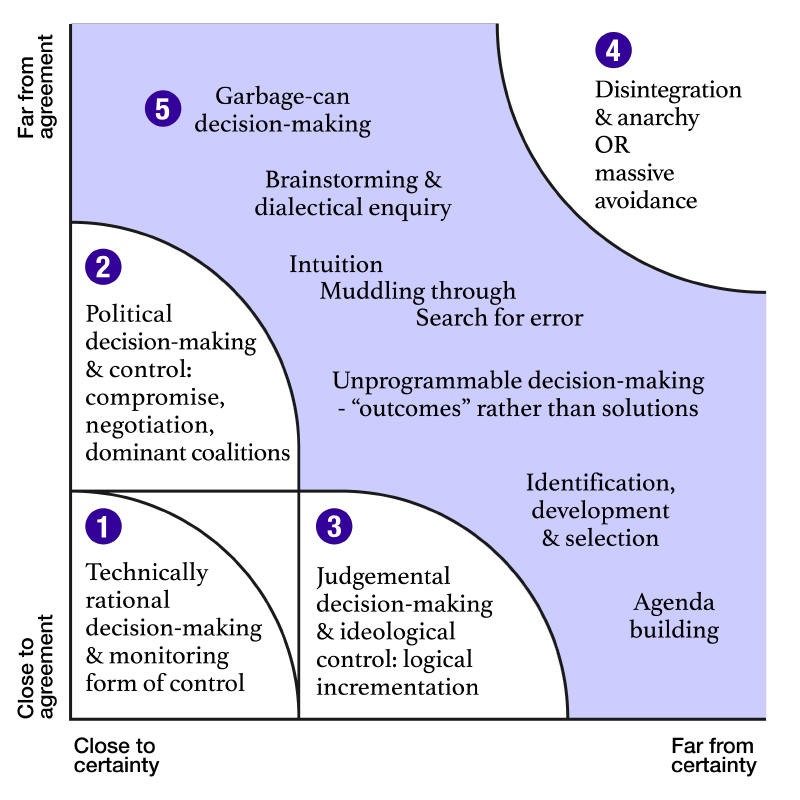

There now seems to be general agreement that health care has many of the characteristics of a complex adaptive system with high levels of interconnectedness. A useful way to look at this is the space defined by levels of agreement about goals and values on one hand, and certainty about the causal relationships on the other.

- No agreement, uncertainty: war on drugs vs decriminalisation

- High agreement, high certainty: clinical guideline

- Low agreement, high certainty: location of a hyper-acute stroke unit

- High agreement, low certainty: reducing ED waits

Many of the issues faced by health care systems are in the middle of this map.

Even apparently obvious candidates for rational decision-making models – for example, which hospitals should be centres for hyper-acute stroke or PCI – can end up in the political realm.

It’s also easy to take the wrong lessons from policies that worked. Policy-makers in England had great success with a combination of quality improvement methods, support and data monitoring to reduce health care acquired infection – but the same approach failed for developing models of integrated care. Whereas the former consisted of well-defined and evidence-based interventions that had little interaction with other processes, the latter was just too messy, contested and unclear.

This calls for a different repertoire from leaders and policy-makers.

Different parts of the system will be in different places on this map over time and there is not a linear trend in any one direction. However, the more complex a health system becomes, the more difficult it becomes to find any system design that works better than where you are now. And, even if you can find it, the view may not be worth the climb.

In the NHS these factors are exacerbated by scale and local heterogeneity. It may look tempting to set not just the ‘what’ of policy but also the ‘how’ from the centre. But this is deceptive. Scale increases complexity; obscures important local issues; and attenuates the relationships and trust required for the agile mutual adjustment that are needed to deal with complexity and high velocity. This may be why, in Europe at least, those health systems that operate at scales of 1-5 million people seem to do better.

Solutions

The response to many of these issues has been the idea of evidence-based policy and to try and get policy-makers to pay more attention to evidence. I remain unconvinced that this provides a sufficient answer – the evidence may not be that helpful and work is required to make it usable.

It’s also important that they commission research to evaluate its impact, although they often prove reluctant to do so.

What we need are:

Better questions and diagnosis. There needs to be more rigour in testing the questions being posed and in particular the easy emergence of group think.

More critical thinking about solutions – particularly where there is group think.

Unfortunately, in the political arena much simpler, less cerebral and more immediately arresting analysis is much more likely to be effective. The question is how to avoid the simple trumping the complex – I don’t have a good answer.

Diversity of disciplines and views – there is more to do to bring in ideas, analytical frameworks and methods from other disciplines such as sociology, political science, anthropology, organisational psychology, geography and so on. Some of these specialists will need a lot of help in translating their ideas and concepts in ways that are useful for policy-makers and, in some cases comprehensible to people outside their discipline. This means that there is an important role for skilled generalists who can span disciplines and methods – but who also know when to bring in a specialist when one is required.

We also need:

- The right balance between top down and bottom up

- More experimentation

- Designing better support for implementation

- Better approaches to the problem of context.

Much of the literature here is highly descriptive but not that helpful.

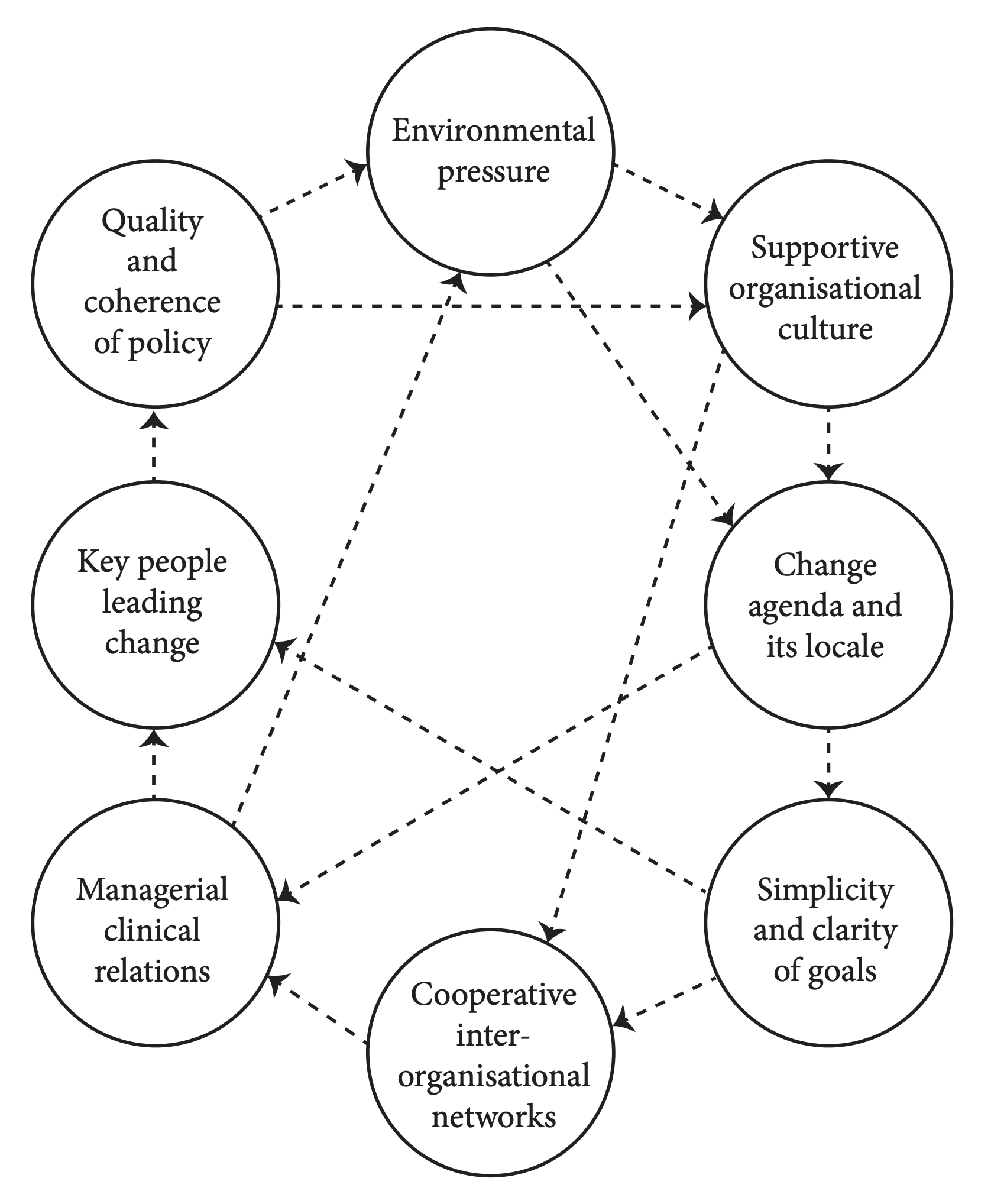

Here is Pettigrew’s framework.

It is a good inventory although, as Paul Bate points out the arrows are at least as important as the bubble. But it doesn’t really help interpret what will actually work where.

Mary Dixon Woods argues that in adapting QI initiatives to their local context, there is a need for a different type of knowledge than is usually deployed. I think the same is true for policy. She goes to Aristotle and others to identify four different types of knowledge:

- Episteme: abstract generalisation, the kind of universal knowledge that is shared and circulated, taught and preserved. It can be seen as knowledge about things.

- Techne: the capability and capacity to accomplish tasks.

She says we also need:

- Phronesis: practical and social wisdom, which is the result of experience and social practice. It is singular and idiosyncratic, acquired by trial and error, and cannot be shared easily. It is a very important check on the hubris and over-rationality of policy designers.

- Metis: intuition that uses ruses, shortcuts, and other tactics to get results, and is embodied into purpose. Like phronesis, it is complex, tacit and difficult to communicate. Metis is the form of ad hoc reasoning best suited to complex social tasks, where the uncertainties are so daunting that intuition and ‘feeling the way’ is most likely to succeed.

Using history and comparative studies. Many policy ideas have been tried before or in other settings and countries. These require care in their interpretation.

Better policy evaluation and learning needs to be a strong part of this.

Finally, all of this needs to be brought together in:

Short digestible synthesis of the evidence – even your mum will not read your 200-page research report.

Bringing these different approaches together will greatly increase the chances that policy will work better. Independent bodies that can speak truth to power or, perhaps less grandly, inject doubt into false certainty; remind people of the history; test that the solutions fit the problems and have the requisite level of simplicity or complexity; occupy a key role and have a duty to speak up and avoid the temptation to be co-opted into the system as well as helping to find new pathways to solutions.

Unlike Lansley’s reforms, we may not, to quote David Nicholson, be able to see the results of this from space, but we ought to experience some improvement closer to home.

Nigel spoke at the Nuffield Trust Summit on 27 February. You can watch the above speech here.