The Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) now being put into action across England are premised on targets to reduce the number of hospital beds that the NHS will need by 2020. As always in the NHS, the reference to “beds” is really a rather old-fashioned way of defining hospital capacity in a health system. They are a tangible shorthand for all the equipment and staff that patients need in hospital.

But our research has shown that many of the initiatives the plans contain, while often good for patients, will not necessarily save money by reducing the need for hospital care. A recent review of all the plans by Sean Boyle and his colleagues at London South Bank University concluded that “there is little reason to believe that these ambitious reductions in demand and pressure on acute services will be achieved in the timescale proposed”. Are they right? We looked at historic hospital use data to see if we could shed any further light on the issue.

Against the tide

Not all the plans published last year give detail on the proposed bed or activity changes they will involve. But enough do to easily stand up Boyle and his colleagues’ description of the plans as “ambitious”. They single out a few of the more significant reductions being proposed as of October 2016:

- Derbyshire: 530 fewer beds by 2020

- Devon (June 2016): 590 fewer beds

- Kent and Medway: 296 fewer beds

- Lincolnshire: 118 fewer beds

- Dorset: 360 fewer beds

- Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland: 281 fewer beds.

Other STPs use activity as their target. The South Bank University study quotes the following figures:

- a reduction in planned inpatient work of 1.4 to 16 per cent

- a reduction in A&E attendances of between 6 and 30 per cent

- a reduction in urgent admissions of between 3 and 30 per cent.

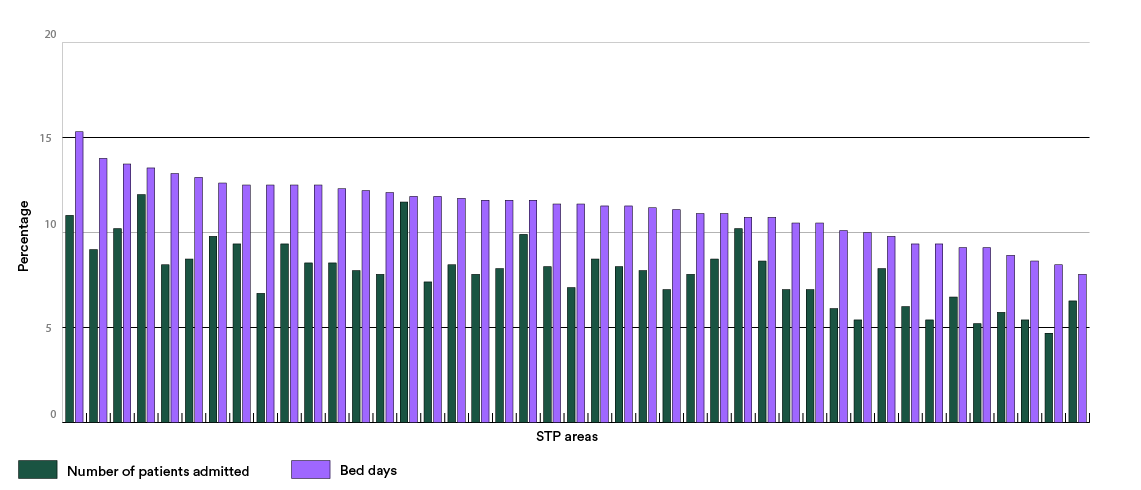

The data we examined shows that STPs will be trying to achieve these reductions in the face of population trends which, all other things being equal, we would expect to significantly increase the need for beds and for hospital care. We used the Office of National Statistics’ figures for population in the coming years, reflecting the growth and ageing of England’s population. Assuming that each five-year age bracket of the population will have similar rates of hospital use and lengths of stay as they do now, we can see that the NHS faces a very large potential increase in demand for both admission and stays in hospital.

The 10,000 bed challenge

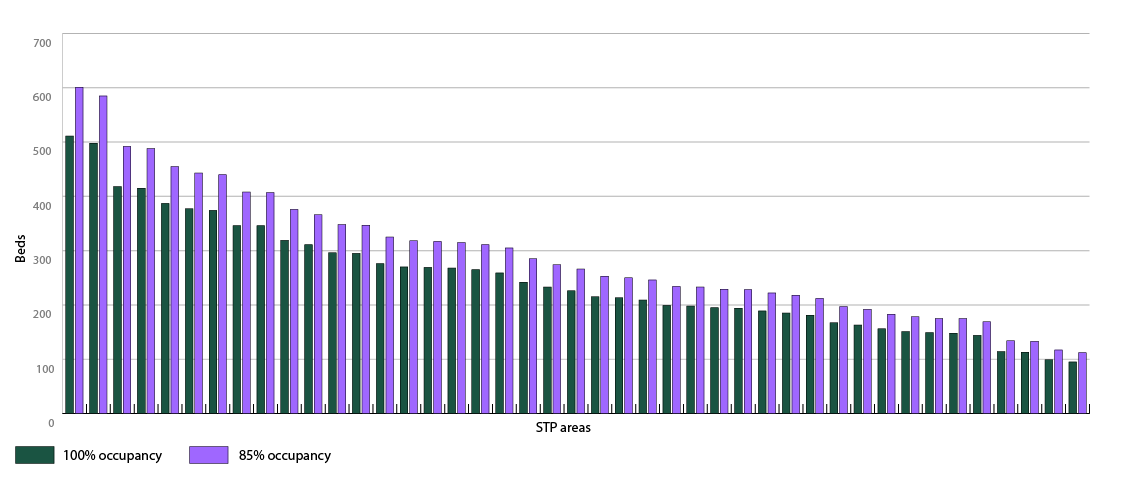

The graphs below show the scale of the increase across different STP areas by 2020. For the number of beds, I have calculated how many beds would be needed to care for patients at the 85 per cent occupancy level traditionally considered ideal for safety. To give an absolute minimum, I have also looked at how many more beds would be needed even if they were run at 100 per cent occupancy – something that in reality is impossible given the need to clean and prepare beds between patients.

These potential increases in activity and bed requirements show the true size of STPs’ ambitions. A very small proportion of the difference may be accounted for because STPs often do not count specialist care beds, funded directly from the centre, but the trends for all beds will show a sizeable increase. Across all STPs our calculations show that far from a reduction, we might expect the NHS to require an additional 10,700 hospital beds – even making the very generous assumption that all could be run at 100 per cent occupancy.

In specific areas, the scale of the gulf can be especially stark. Dorset’s STP commits it to a 20 per cent reduction in hospital beds – yet the demographics suggest it would need 10 per cent more. Kent and Medway plan a 10 per cent reduction in beds against a 12 per cent potential increase.

Is this feasible? In the past, as we have shown, the NHS has managed to deliver large amounts of increased activity with somewhat fewer beds. However, the reduction in bed numbers has been slow – around 6 per cent over the last six years. Perhaps more importantly, this has come alongside rising problems: periodic crises, systemic failure to meet waiting times targets, unsustainably high occupancy, and staff burnout.

Factoring in improvements in health and care

In the longer term, the hope is that the population is growing more healthy – that today’s 65-year-olds are healthier than those 20 years ago, for example – and that this might offset some of this growth.

However, there is some evidence the effects of better care can cut the other way as well. Today’s 75 and 85-year-olds include more people who have survived life-threatening illness, and so may be less healthy and have seen less improvement in mortality rates than their predecessors.

What’s more, progress can also in itself lead to more activity being carried out in health care. For example, the rise of keyhole surgery and endovascular treatments carried out along veins and arteries has meant that people who would previously not have survived a conventional operation can now be offered procedures. The rapid growth of short-stay units and falling lengths of stay in hospital also can also create opportunities for more activity by freeing up space.

Admission arithmetic

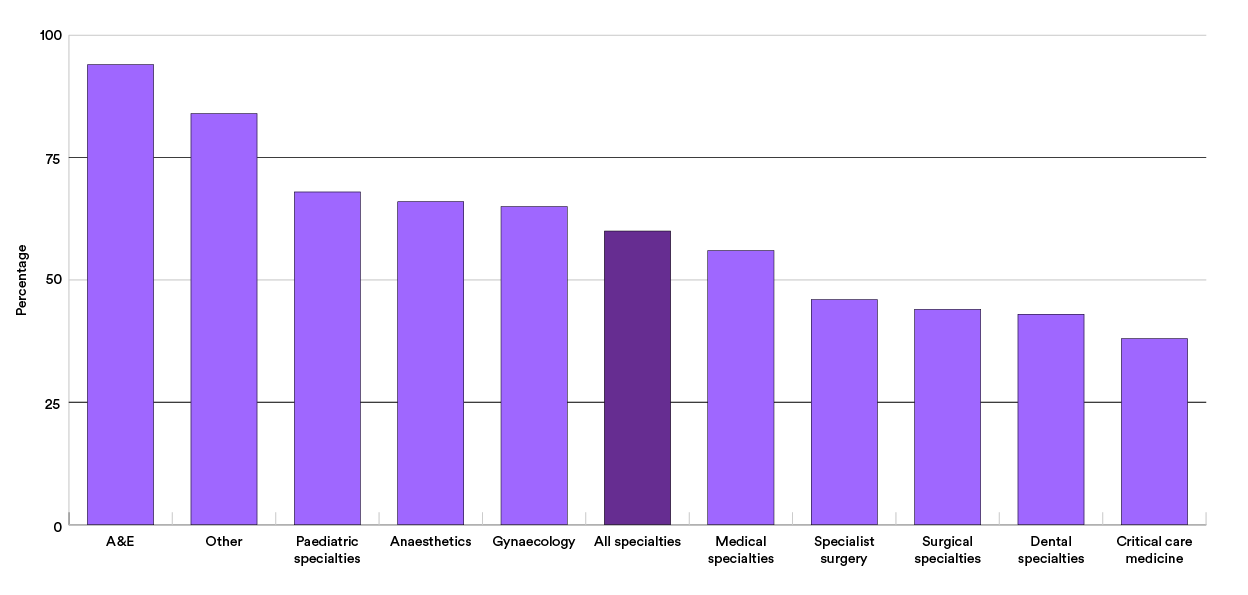

To address the issues, plans put quite a lot of emphasis on preventing the need for people to be admitted to hospital. The data we looked at suggests that there is definitely scope to do this, but it also demonstrates freeing up space and money will not be easy.

A significant proportion of patients only stay 0 or 1 day – a fact sometimes taken to show that they may not have required hospital in the first place. However, even if this is true, it is likely that in general these patients need investigations including physical examination and other professional input and treatment to exclude the need to admit. This may mean that they will cost almost as much whether or not they are formally admitted. The reduction in the strain on frontline staff and in the admission of patients who might have had a more extended stay will be beneficial.

What’s more, by definition these patients use very few beds – so significant reductions in admissions cannot be assumed to translate into a similar reduction in bed requirements.

There is significant variation between STP areas in the proportion of patients who do not stay overnight for non-elective cases – from 23 per cent in Humber, Coast & Vale to 60 per cent in North Central London. There are also a significant number of elective inpatients who do not stay overnight, and again major variations in this proportion between STP areas. This probably reflects a different approach to coding and local policy and some differences in the service model in some providers.

Focus on the few, not the many?

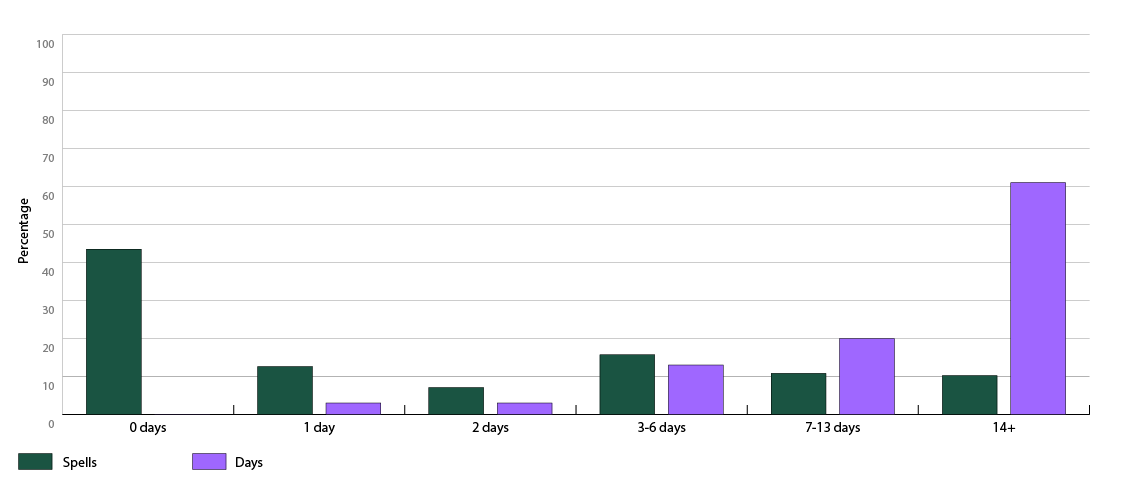

The data suggests there may be more scope to release beds or capacity by looking at the minority of patients who have to stay for a long time. In general across acute specialties, only 9 per cent of all patients stay more than seven days. However, these patients use over 72 per cent of the total bed days. 41 per cent of the total are used by those staying 21 days or more.

There is, unsurprisingly, a close link to age. 56 per cent of all the bed days of all inpatients staying over seven days are accounted for by patients aged over 60, and 30 per cent by those over 80.

The chart below divides patients needing unplanned medical care into different categories based on how long they stay in hospital. The green bars show what proportion of patients are in each group, and the purple bars show what proportion of bed days they use.

In my previous blog on delayed transfers of care, I highlighted the fact that a significant number of inpatients could be cared for in other settings that are likely to be better for them, and could well be cheaper. This assumption is reflected in some of the STP plans. But crucially, those settings need to be ready to receive them – and the intermediate care audit suggested that there is a major shortage of certain types of services. The extent to which STPs contain matching investment in rehabilitation, home care and different types of intermediate care is often unclear. In some cases we looked at in more detail, it appears to be insufficient to absorb the number of people it is hoped might be redirected from hospital.

However, the data does show that the proportion of patients with the longest stays has already been falling over time, even with out-of-hospital services being very stretched. That implies the problem – and the answers to it – may not just be about the capacity to treat people elsewhere. The decision processes and the bureaucracy associated with continuing care decisions and discharge arrangements may also still be worth attention, and improving them could offer ways to make patients flow through the system more smoothly and improve overall capacity. This might be easier to achieve than some of the more heroic assumptions about reducing the number of people needing care.

The road ahead

Our look at the data can tell us a little more about how those ambitious plans might succeed or fail. Reducing the number of admissions, as well as being difficult, may not free up as much space as might initially be expected. The scale of the challenge facing STPs over five more years of relentlessly tight resources means that some very big shifts in lengths of stay will be required from a relatively small group of patients. The investment in alternatives to hospital will need to be on a significant scale to achieve and sustain this.

Above all, though, the judgement of the London South Bank review about the overall size of the task is borne out. Wherever the best place to start might be, STPs have a mountain to climb.

Hospital Episode Statistics data © 2015/16, re-used with the permission of NHS Digital. All rights reserved.

Suggested citation

Edwards, N (2017). "Will the NHS really need fewer beds in the future?". Nuffield Trust comment. www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/will-the-nhs-really-need-fewer-beds-in-the-future