Ahead of the 2017 General Election, polls show that the public see the NHS and leaving the European Union (EU) as the two most serious issues facing Britain. What must not be overlooked is that these are closely connected. Brexit will have a lasting impact on health and social care in the UK, and getting it wrong risks leaving already strained services with an impossible task.

This briefing focuses on the essentials that the next government needs to secure for the NHS and social care, and the people who use these services. The Nuffield Trust will continue to explore these and other important issues – including the future funding of scientific research, and the free movement of other clinical and research groups – through an ongoing series of events and briefings.

Key points

- The Brexit deal will affect how much money is available to spend on the NHS. The health service needs a deal with Europe that enables the future funding increases all parties agree it needs. While the £350 million figure used during the EU referendum is a myth, there is the scope for a significant funding boost when the UK stops paying its EU membership fees, which could give the NHS enough additional money for one or two years.

- On the other hand, the economic slowdown associated with Brexit is likely to reduce the money available by a greater amount in the short term. It is in the interests of the health service and patients for Brexit to involve as little economic disruption as possible.

- The NHS is depending on EU migrant nurses to prevent the serious problem of understaffing from getting even worse. There must be a commitment either to continue to allow substantial nurse migration after Brexit, or to step up domestic training, even if this proves more difficult and more expensive than current policies anticipate.

- Social care faces a shortfall of as many as 70,000 workers by 2025/26 if net migration from the EU is halted after Brexit. Either substantial net migration from the EU will have to continue, or wages in the sector will need to rise to attract more domestic workers.

- If all the British pensioners who currently receive health care in other countries through EU agreements had to return, caring for them would require the NHS to spend an extra £1 billion a year. This is twice as much as we pay for them to receive care abroad, and there would also be a need for extra beds equivalent to two new hospitals. Every step should be taken to try to secure a deal that allows them to keep receiving care where they now live.

- It is in the interests of British patients to remain part of a European market for medicines, so that new products are introduced in Britain early and the NHS can draw supplies from across the continent. This will require a deal where the UK continues to work in close alignment with the European medicines regulator.

- There are other areas of regulation, such as procurement and working time, where the NHS might make use of more flexibility, and the next government should think carefully about what the health service needs before developing their policies on these.

The NHS needs a deal that allows for future increases in its budget

The English NHS is under exceptional financial pressure, more than halfway through the most austere decade in its history. Real-terms funding has only been rising at an average of 1% each year, compared with a historical average of 4%. Under current plans, in some years in the next parliament this will actually mean a cut in funding per person. This tight financial settlement is contributing to pressures on waiting times for patients. It has been mirrored across Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Political parties across the spectrum agree that significant extra funding will be needed in the years after Brexit. Both the Labour and Conservative parties have pledged significantly higher spending out to 2022/23 in their manifestos, but Nuffield Trust analysis suggests still more would be needed to keep up with historical trends or with rising demand and costs in the service. Nor is this simply a question of the next few years: Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt told the Health Select Committee: “It is a given that over coming decades we will need to put more into the health and social care system”. Labour’s Jonathan Ashworth has called for “ambitious” long-term financing. Polling suggests that voters may accept this: they are even willing to pay more tax to support the health service.

There are three ways in which Brexit might change the amount of money available to the NHS, making it more or less possible to deliver these election commitments and to build on them in the future.

Funding our NHS instead?

The first is by making more money available directly through ending the UK’s contribution to the EU. During the EU referendum, the winning side famously used the slogan “We send the EU £350 million a week, let’s fund our NHS instead”.

In reality, Britain’s average net contribution to the EU in recent years has been £7.1 billion, or around £137 million a week. Somewhat more could be freed up if we did not replace all of the money the EU now gives our farmers, deprived regions, companies and scientists. Much less would be freed up if the UK agrees to settle outstanding liabilities in a “divorce settlement”, as the last government said it intended to do – although this would eventually be paid off and the money freed up again. Less would be available on a permanent basis if we continue to contribute to the EU budget, which the last government said was possible and which no party’s manifesto rules out.

If much of this money was put into the NHS, it would at least meet the more specific pledge of an additional £100 million each week made by leaders of the Leave campaign. Taking into account the funding formula for devolved countries, this would cost a total of £6.1 billion, giving the English NHS an increase of £5.2 billion with matching funds across the UK.

This would be a significant and welcome increase, although not a permanent solution. It would account for a 4.1% increase on top of the Department of Health budget for 2020/21 (the latest year for which we currently have a planned budgetary total). This is slightly more than one year’s worth of the funding increases of 3.7%, which the NHS has typically received through its history, or around two years’ worth of increases keeping up with economic growth, which the House of Lords NHS Sustainability Committee called for as a minimum after 2020. It could account for the majority of funding pledged by Labour or the Conservatives in their manifestos, or, if added to this, could close some measures of the gap we still calculate will emerge by 2022/23.

The bigger picture

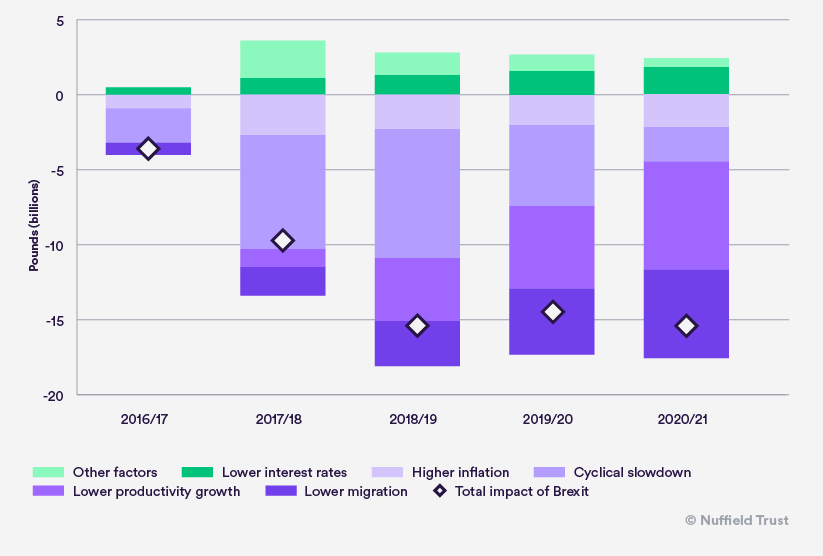

However, there is the potential for any extra funding made available to be balanced out by a second effect. The UK government may experience lower tax revenue and higher welfare spending due to the short-term economic slowdown expected to be associated with Brexit. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) last year projected a £15.2 billion hit to the public finances by 2020/21 as a result of Brexit. The causes of this are broken down in Figure 1. If shared out equally across the public sector based on its current make-up, this would mean a £2.4 billion reduction in annual NHS spending in England alone. There is, of course, an option to counterbalance this with tax rises or sharper cuts elsewhere.

As the OBR says, there are also “downside risks if the path to Brexit is bumpy” – which could make a much bigger hole in the public finances. The Nuffield Trust has no expertise in what sort of deal will be best for the wider economy – but we can say that getting a deal which meets this test is clearly in the best interests of the NHS.

The Brexit bill?

Lastly, Brexit could mean that the NHS needs more money than it otherwise would. The sections below examine some of the potential items on the bill for Brexit. They could include £100 million or more from a fracturing of the medicines market; as much as £1 billion for caring for pensioners who have to return to the UK; and potentially several hundred million pounds in additional pay and training to compensate for lost EU migrants. Many of these items could be minimised or eliminated with the right deal.

The NHS needs a deal that allows nurses and social care workers to keep migrating from Europe – or a government committed to replacing them

The NHS faces a serious shortage of staff in key areas. The National Audit Office found that 50,000 clinical roles were left vacant in England. The scale of the shortfall in nursing means nearly one in ten posts goes unfilled. Scotland and Wales are also seeing clear signs of shortages.

Social care, which includes care homes and domiciliary care for the elderly, is a crucial support to the NHS and many of its patients. It too has seen a steadily rising vacancy rate; up to 7% in England in the most recently recorded year.

The UK has long depended disproportionately on doctors from overseas to fill medical posts. In recent years, it also appears to have become increasingly reliant on nurses and social care workers migrating from the European Economic Area (EEA; includes the EU, Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein). Both Labour and the Conservatives agree that Brexit will mean the end of free movement of labour from Europe, a radical shift in the UK’s migration policy. It is vital that the NHS gets a deal that helps rather than hinders it in dealing with the staffing crisis.

The nursing shortfall

Since the middle of the last parliament, a rise in the number of nurses required by the English NHS due to the ageing population and a renewed emphasis on safe staffing has collided with a workforce planning system which failed to anticipate this. The result has been a recurrent shortage which lies at the heart of the wider workforce issue in the NHS. Associated with this, and doing something to ameliorate it, there has been a dramatic rise in nurses migrating from the EEA, so that by last year almost a third of newly registered nurses in the UK had trained in the EEA.

Introducing a stricter system for migration from the EEA would risk worsening the situation. Modelling from the Department of Health published in the Health Service Journal projects a shortage of up to 20,000 nurses by 2025/26 if EEA migration is shut off – from a starting point at which shortages are already in the tens of thousands. This is the projected possible shortfall even if all initiatives to manage demand on the NHS are as successful as the Department of Health believes they could be. In reality, as Nuffield Trust analysis has shown, many are highly uncertain: a higher level of rising activity could increase this shortage to over 50,000.

The picture could be even worse. This model seems to assume that at least current EEA migrants will be allowed to stay, and that migration is maintained until Brexit. Yet despite calls from a very wide range of NHS bodies, the right of EEA staff to stay has still not been confirmed. There are signs that EEA migration is already falling sharply ahead of Brexit, and that the number leaving is rising.

There are two ways in which a shortfall on this scale can be avoided. The first would be to exempt nurses from migration restrictions following Brexit. Within the options reportedly under consideration, this could be done through largely continuing freedom of movement generally, or by having a work permit system which allocated several thousand permits to NHS nursing roles each year. Another option would be to have a shortage occupation system, as currently operates for non-EEA migrants. This exempts certain groups from salary requirements, and puts them at the front of the queue for the limited number of visas available. Nurses have been added to this list as of 2016, but an overall cap of 5,000 has been set: there is a limit to what the Migration Advisory Committee can allow within a system with an overall cap on numbers. This might not, then, be enough on its own unless the overall number of skilled migrants allowed is considerably higher than it currently is for non-EEA migrants..

The other alternative would be a dramatic increase in the training of nurses domestically. Labour and the Conservatives are currently campaigning on directly opposite proposals to achieve this. The Conservatives in government introduced plans to bring in student loans for nursing and allied health profession students, in order to fund an increase in training places. Labour plans to repeal this provision, pointing out that it seems to have led to a sharp fall in the number of applications to study nursing this year. The reality is that the policy’s impact cannot yet be known, but we certainly cannot be sure that it will fill the gap where years of previous workforce planning have failed. Furthermore, there will be a lag of three years between starting to train more nurses and any impact on the qualified workforce – already taking us a year past Brexit. Guaranteeing the safe staffing of the NHS after Brexit requires, above all, a commitment to deliver the supply of nurses the NHS needs, backstopped by a commitment to put in substantial funding if required.

Social care should not be overlooked

The social care sector has also become increasingly reliant on migration from Europe to keep pace with rising need. Although EU migrants still account for only 7% of the 1.3 million social care workers in England, that figure has risen from 5% just three years ago (Skills for Care, 2016).

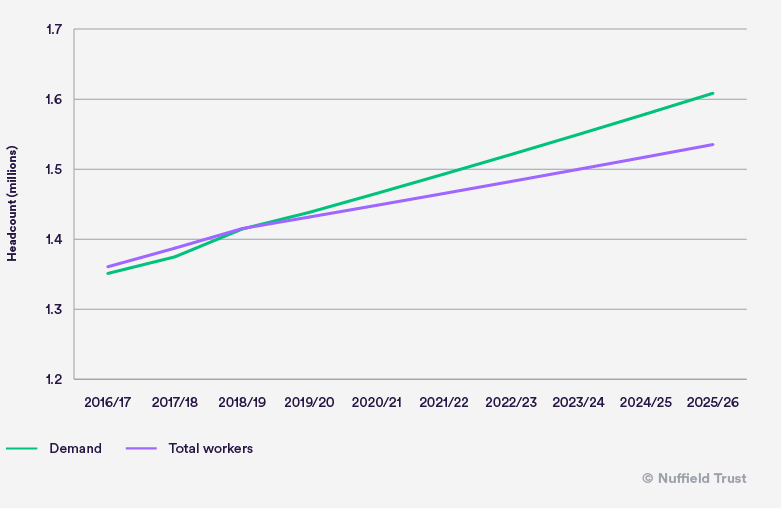

Figure 2 shows what would happen if we project recent trends for the number of workers without further EU migration after 2019, against a rate of rising demand based on calculations by the London School of Economics and Political Science.[*] The result is a gap of more than 70,000 by 2025/26.

Because they often have low salaries and limited formal qualifications, social care workers are less likely to arrive under systems generally geared to encourage higher skilled migration. Yet this suggests there is again a very serious case for generous treatment under a work permit or shortage system.

As with nurses, social care workers could also be replaced by increasing the domestic workforce. The problems faced may be quite different. Social care workers do not need particular university-level training, but their employers must compete with other sectors such as retail in order to hire them. The implication is that wages might need to rise above the National Living Wage in order to fill the shortfall. Given that wage costs account for almost half of social care spending, this could add a significant extra cost to what is already a sector under intense financial strain, both for the local authorities buying care and for provider companies.

The NHS needs a deal that allows expat pensioners to continue to receive care where they live

Under the EU’s S1 programme, pensioners have the right to go to any other member state and receive the same health care rights as the local population, paid for by their native country. Currently, some 190,000 British pensioners have chosen to leave the UK under this scheme. The UK Department of Health pays around £500 million to other countries to cover their care costs.

However, the costs of ending the S1 scheme could be considerably higher. If British pensioners lost their health care cover in EU states and had to return to the UK in get the care they need, the extra annual costs to the NHS could amount to as much as £1 billion every year. This figure has been calculated using NHS England’s estimates for the cost of different age groups, which reflect that older people tend to need more care. It assumes that pensioners abroad have the same age structure as over-65s resident in England. It is around double the figure currently paid for the care of these people abroad. It is possible that UK pensioners abroad under the S1 scheme would be relatively healthier, and their care could cost less. However, evidence given by the Department of Health suggests they also believe costs could be close to twice as high if these pensioners were treated in the UK.

Even more difficult would be finding the staff and beds these people might need. Looking at relative hospital demand by age group, we might expect 190,000 people to require 900 more hospital beds and 1,600 nurses, as well as doctors, other health professionals, and support staff such as porters. This number of additional beds would be equivalent to two new hospitals the size of St Mary’s Hospital in London. Unlike funding, these resources cannot simply be brought on stream at will: as discussed above, there are already too few nurses for existing requirements, while hospital bed occupancy is already at very high levels, especially in winter.

It may not be easy to continue after Brexit with reciprocal health care arrangements like S1 – or the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) that covers travellers. These arrangements fall under the EU Social Security Coordination, and are considered a part of the system of freedom of labour, from which both Labour and the Conservatives say the UK will withdraw. However, it is in the best interests of the NHS to see if a continued deal can be agreed.

There is also the possibility that this might be the tip of the iceberg. While precise estimates vary, there are a total of around one million UK citizens resident in the EU. If the next government fails to secure a deal to allow them to retain the rights they currently hold, the NHS will need to care for all those forced by law or circumstances to return.

The NHS needs stable rules, but with opportunities to go its own way fully explored

European regulations, laws and regulators govern many aspects of health care, social care and life sciences in the UK. In many cases, these are the infrastructure of a single market which benefits the NHS and which should be retained as much as possible. However, there are also areas where Brexit may open up new possibilities to work differently.

Stability and continuity come first

Perhaps the most important EU regulations for the NHS are those which govern medicines. Currently, the UK is subject to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), based in London, which works with the British Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and other national regulators to approve medicines for sale across the EU and to guarantee their safety. Under many forms of Brexit, it is likely that we will no longer be a member of the EMA. This is especially the case if Britain wants to leave the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, as the last government intended. However, there are compelling reasons to retain as close a relationship as possible.

The EU accounts for 25% of the world’s sales of medicines, and its regulator, along with the USA’s, is one of two considered ‘globally significant’ by the pharmaceutical industry. The UK, meanwhile, accounts for just 3%. As a result, while it is currently part of a high priority market for new drugs and treatments, as a separate market it would get new treatments later. Indeed, companies might not find it worth the cost of going through the process of getting some new drugs approved in the new, smaller British market at all.

The NHS also benefits from being able to buy from such a large market. The depth of supplies available helps avoid the risk of shortages. The ‘parallel trade’ where medicines are bought from countries where they are cheaper than the UK saves pharmacists contracted with the NHS money, helping pay for their services with less government funding, and acts as a competitive pressure on the prices of the pharmaceutical industry. The direct benefits of this have been estimated at £100 million. Studies (often funded by rival parts of industry) disagree about how much more is saved through lower prices, but it may be a significant proportion of this again (HDA UK; Enemark and others, 2006; Kanavos and others, 2004).

Short of remaining a member of the EMA, the UK could look to remain part of one market through an ongoing co-operation agreement where it followed EU regulatory decisions, in exchange for some influence.

Another area where stability and continuity should take priority is the regulation of clinical trials. The EU’s old clinical trials directive was widely criticised for being too bureaucratic and deterring research. A new set of regulations due to be introduced in 2018 is seen as an improvement. Universities and science bodies told the Science and Technology Select Committee that they favour the UK going ahead with the new directive, to avoid the bureaucracy of changing regulations mid-trial and of Britain having a different set of rules in trials which are often cross-border. There would be a risk that having different regulation to other European countries would discourage trials including NHS patients, taking away funding for trusts and making it harder to recruit the best scientists and doctors.

Taking back control?

But there are also areas where the NHS might have a legitimate interest in considering diverging from EU law and regulation.

Firstly, the procurement and competition laws which force the English NHS to tender contracts openly, and forbid co-operation between hospitals which undermines competition, are backstopped by EU law. Although they are written into British law as well, Brexit could open the door to changing this – a prospect welcomed by NHS England Chief Executive Simon Stevens. However, it is equally possible that similar rules on competition could be built into any new trade deal with the EU or other countries. Whether or not these laws are desirable or not is open to debate: what is clear is that the government should make sure its negotiating position reflects a coherent view of whether the NHS should be subject to them.

Secondly, the Working Time Directive sets minimum standards for working hours and rest periods. Particular precedents and limitations apply to doctors. It has been criticised by several medical royal colleges, including the Royal College of Physicians and the Surgeons of Glasgow, for limiting the training time available to junior doctors, and the scope for them to work in a stable team – even as restrictions on working hours have become accepted into successive contracts. Again, there are valid arguments on both sides. But it is important that negotiations are based on a clear understanding of the far-reaching implications of these rules for the way NHS staff work and train.

Conclusion

The NHS was under pressure from constrained funding and growing workforce problems well before the referendum to leave the EU last year. There is a risk that the decision to leave the EU will amplify these pressures, given its potential impact upon both the overall size of the economy and the supply of overseas staff to both health and social care services. However, a departure from the EU could contain other benefits for the NHS if further funds can be found to invest in services, and changes in the regulatory framework can work to support positive change. Whether or not these benefits will outweigh the significant workforce and financial costs Brexit could mount on already stretched services remains to be seen and will depend largely on the NHS being recognised as a significant priority as we enter some of the most important negotiations in Britain's history.

[*] Calculations from the Personal Social Services Research Unit shared with the Health Foundation.