Since 1983, NatCen Social Research’s British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey has asked members of the public about their views on, and feelings towards, the NHS and health and care issues generally. The latest survey was carried out between July and October 2017 and asked a nationally representative sample of 3,004 adults in England, Scotland and Wales about their satisfaction with the NHS overall, and 1,002 people about their satisfaction with individual NHS and social care services.1

In the analysis that follows, the differences highlighted are statistically significant at the 95% level unless otherwise stated.2

Key findings

Satisfaction with the NHS overall

- Public satisfaction with the NHS overall was 57% in 2017 – a 6 percentage point drop from the previous year. At the same time, dissatisfaction with the NHS overall increased by 7 percentage points to 29% – its highest level since 2007.

- Older people were more satisfied than younger people: 64% of those aged 65 and over were satisfied with the NHS in 2017 compared to 55% of those aged 18 to 64. Between 2016 and 2017, satisfaction fell among all age groups.

- The four main reasons people gave for being satisfied with the NHS overall were: the quality of care, the fact that the NHS is free at the point of use, the attitudes and behaviour of NHS staff, and the range of services and treatments available.

- The four main reasons that people gave for being dissatisfied with the NHS overall were: staff shortages, long waiting times, lack of funding, and government reforms.

Satisfaction with NHS and social care services

- Satisfaction with GP services fell to 65% in 2017 – a 7 percentage point drop from the previous year. This is the lowest level of satisfaction with GP services since the survey began in 1983 and the first time that general practice has not been the highest rated service.

- Satisfaction with outpatient services was also 65% in 2017. The change from the previous year was not statistically significant.

- Satisfaction with inpatient services was 55% in 2017, down by 5 percentage points from 2016.

- Satisfaction with accident and emergency (A&E) services was 52% in 2017. The change in satisfaction from 2016 was not statistically significant.

- Satisfaction with NHS dentistry services was 57% in 2017. The change from the previous year was not statistically significant.

- Satisfaction with social care services was 23% in 2017. The change from the previous year was not statistically significant. At the same time, dissatisfaction with social care services increased by 6 percentage points in 2017 to 41%.

How satisfied is the British public with the NHS overall?

In its 70th year, polling shows that the NHS remains a treasured national institution that is a key part of the British national identity. The public is unwavering in its support for the underlying principles of the NHS and consistently prioritises the health service for extra government funding, above other public services like education and welfare.

Yet while support for the founding principles of the NHS changes little over time, the public’s satisfaction with the service is not as constant, fluctuating in response to changes in issues like waiting times, patient experience, funding and the political environment.

For 35 years, the BSA survey has asked a sample of the public ‘how satisfied are you with the way the NHS runs nowadays?’. Responses to this question have provided a unique insight into how public views on the NHS change over time.

In 2017, satisfaction with the NHS was 57% (combining the percentages of ‘very’ and ‘quite’ satisfied responses). This is 6 percentage points lower than the previous year.

At the same time, public dissatisfaction with the NHS grew to 29% in 2017, a 7 percentage point increase from the previous year, and the highest level of dissatisfaction with the NHS since 2007. Dissatisfaction with the NHS has risen rapidly over the past three years: between 2014 (when dissatisfaction was at an all-time low) and 2017, the level of dissatisfaction almost doubled, rising from 15% to 29%.

Because of these changes, net satisfaction (calculated as satisfaction minus dissatisfaction) was 28% in 2017 – its lowest level since 2007.

Why is the British Social Attitudes survey so important?

There is a lot of different polling about people’s views and attitudes towards the NHS. What are the differences, and where does the British Social Attitudes survey fit in?

Surveys that differ in their findings often do so because of different question wording or approaches to conducting the survey. For example, large-scale patient experience surveys ask people about their experiences of using the service. Their results are relatively stable over time, usually changing by only a small amount each year. This is partly because participants tend to have a particular experience of care (for example in maternity or cancer services), and often a long-standing relationship with a clinician or health care organisation, in their mind when responding.

Polling on public attitudes is different, because people tend to focus on wider issues as well as their experience of care when responding. Not everyone responding to a public poll will have used the NHS recently.

Public polling about the NHS asks a range of questions that explore subtly different aspects of satisfaction. For example, a recent Ipsos MORI survey found that 62% of people thought the NHS would get worse over the next few years. This measures optimism about the future and so is not the same as the BSA survey question about current satisfaction with how the service is run.

Surveys may also yield different results because they use different methodologies, cover a different population or ask questions in a different order.

The BSA is widely viewed as a robust survey that uses a randomly selected sample of the British public, and it is conducted using a ‘gold standard’ survey methodology that involves a face-to-face interview with multiple follow-ups with non-responders. The survey is conducted the same way every year and the data provides a rich time trend going back to 1983, adding a depth and context to the findings that no other measure of NHS satisfaction can give us. As a result, when satisfaction falls in the BSA survey, we are as confident as we can be that it reflects a genuine change in public attitudes.

Who is most satisfied with the NHS?

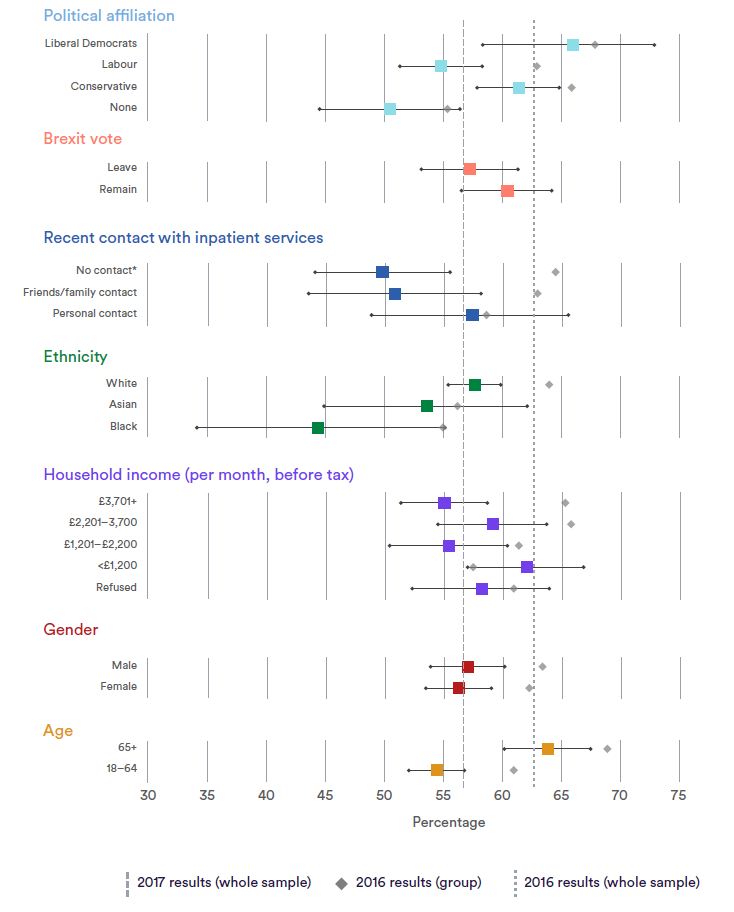

Figure 2 shows how satisfaction with the NHS differs between groups in the population. For each group, we have included black bars showing the 95% confidence interval around each value. These show the range of values that, based on the survey data, we can be 95% certain include the true satisfaction level for each group. Where the confidence intervals overlap, we cannot be

confident that the true satisfaction levels differ between groups.

Satisfaction levels differ depending on the respondent’s age and ethnicity. Younger respondents under the age of 65 report lower levels of satisfaction (55%) than those aged 65 and older (64%). Respondents aged 75 and older report even higher levels of satisfaction (69%).

Looking at the data on ethnicity, respondents who identify as Black report lower levels of satisfaction (44%) than respondents who identify as White (58%). Satisfaction among respondents who identify as Asian (54%) was lower than among White respondents, but the difference was not statistically significant. Patient experience surveys also find that patients from minority ethnic groups report more negative experiences, and this may be a contributing factor to differences in the satisfaction levels reported in the BSA survey.

The differences in satisfaction levels between men and women; across different income groups; between those who have and haven’t had recent contact with NHS inpatient services in the past year; between those who voted to remain or leave in the 2016 EU referendum; and between supporters of different political parties are not statistically significant (although supporters of the Liberal Democrats have a significantly higher level of satisfaction than respondents who support no political party).

The grey diamonds in Figure 2 show the results for the 2016 BSA survey. Between 2016 and 2017, levels of satisfaction reduced in every group that we looked at, although not all of the changes are statistically significant. The only group who reported a higher level of satisfaction in 2017 compared to 2016 was people in the lowest income quartile (although again the change was not statistically significant).

How satisfied is the British public with different NHS and social care services?

The survey also includes a set of questions that explore public views about specific health and social care services. When interpreting this data, it is important to remember that this is not a patient experience survey. It is a survey of public views, and many respondents may not have used the service they are being asked to comment on in the past year. Because of this, the survey asks respondents to draw on ‘your own experience, or from what you have heard’, meaning the experiences of family and friends and information from other sources such as the media are likely to influence their responses.

Of the six questions on satisfaction with individual health and care services, GP satisfaction is the closest that the BSA survey gets to an experience measure. Most of the people who responded to the survey will have visited their general practice in the past year, either for themselves or with a family member.

In 2017, satisfaction with GP services fell to 65%, the lowest level in the survey’s 35-year history (Figure 3). Satisfaction dropped by 7 percentage points between 2016 and 2017, which is the biggest one-year change since the survey began. In line with this, dissatisfaction with GP services was at an all-time high in 2017, jumping 6 percentage points to 23%.

NHS England’s national GP patient survey (which covers England, rather than Britain) includes a similar question that provides a useful comparator for these results (‘Overall, how would you describe your experience of your GP surgery?’) . In a similar way to the BSA satisfaction measure, the proportion of patients who describe their experience as ‘good’ has steadily decreased

in recent years, from 89% in July 2012 to 85% in July 2017. The proportion describing their overall experience of making an appointment as ‘good’ also decreased from 79% to 73% over the same period.

Satisfaction with NHS dentistry was 57% in 2017, 4 percentage points lower than the previous year, but the change was not statistically significant (Figure 4). Satisfaction with dentistry services remains at one of the highest levels seen this century. As we discussed last year, the relatively high rates of satisfaction compared to the mid-2000s is likely to be partly explained by efforts to increase access to NHS dentistry services over the past 10 years. NHS England’s GP patient survey also asks respondents about their overall experience of NHS dentistry services. It reported no change in patient satisfaction between 2016 and 2017, but there has been a small increase since 2012 (from 83% to 85%).

The BSA survey also asks about satisfaction with social care services (Figure 4). For the past six years, this question has defined social care as ‘personal support services provided by local authorities for people who cannot look after themselves because of illness, disability or age’. In 2005 and 2007, the question was worded slightly differently, not mentioning local authorities in its definition of social care. Figure 4 shows that levels of satisfaction with social care have been declining since 2007. In 2017, satisfaction with social care services was 23%. Although the change

in satisfaction from the previous year was not statistically significant, satisfaction was 7 percentage points lower than in 2012. Dissatisfaction with social care services increased by 6 percentage points in 2017 to 41%.

The survey also asks about satisfaction with hospital services (Figure 5). Satisfaction with inpatient services dropped by 5 percentage points in 2017 to 55%, following four years in which there was no statistically significant change. Meanwhile, satisfaction with outpatient services remains relatively high, historically speaking, at 65%, and the change from the previous year was also

not statistically significant. Satisfaction with A&E services, which was 52% in 2017, has not changed significantly for the past three years.

Levels of satisfaction with the three hospital services included in the survey broadly follow the same trend as satisfaction with the NHS overall. This is perhaps because these are services that the public has less personal experience of, so – as is likely the case with overall NHS satisfaction – respondents draw on a range of sources to inform their views about the NHS, from friends, family and elsewhere.

Figure 6 brings together public satisfaction data for health and social care services and the NHS overall in 2017. As in previous years, satisfaction with the social care services provided by local authorities is far lower than satisfaction with health care services.

A higher percentage of respondents say that they ‘don’t know’ what their satisfaction level is or provide a neutral answer that they are ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’ with social care compared to other services. This is likely to reflect a lower level of understanding among the public about what social care services actually are, coupled with less experience of using them.

In 2017, net satisfaction with social care services (calculated as satisfaction minus dissatisfaction) was –18%, whereas net satisfaction with the NHS overall and individual NHS services ranged from +28% to +52%.

Figure 7 presents trends for all of the BSA survey’s health and social care satisfaction measures since 1983. It shows that, throughout the survey’s history, general practice has received higher satisfaction ratings from the public than other health and care services and the NHS overall. The difference was most stark in the 1990s and early 2000s, when satisfaction with general practice was around 20 percentage points higher than satisfaction with hospital-based services and the NHS overall. However, the steady decline in satisfaction with general practice in recent years (from 80% in 2009 to 65 per cent in the latest data) and increases in satisfaction with hospital-based services have led to a convergence in satisfaction rates across services. In 2017, for the first time since the survey began, general practice was not the highest-rated service: outpatient services received the same satisfaction rating (65%) as general practice.

Figure 7 also shows that between 1983 and 2003, satisfaction with the NHS overall was lower than satisfaction with individual NHS services. From 2004 onwards, improvements in overall satisfaction brought it closer to satisfaction with individual services. (Overall satisfaction was higher than satisfaction with A&E, inpatient and dentistry services and lower than satisfaction with GP and outpatient services for most of the period from 2004.)

What drives public satisfaction?

Over the last few years, we have asked some additional questions to try to better understand the responses to the BSA survey’s question about satisfaction with the NHS overall. We know that the public draw on more than their experience of NHS services when reporting their satisfaction level, but understanding why satisfaction changes from year to year is not a precise science. To explore this further, we ask respondents why they said they were either satisfied or dissatisfied with the NHS overall. The question presents people with nine possible reasons to explain their response, and asks them to select up to three. The lists of reasons were developed with a group of respondents who were asked an open-ended question about why they were either satisfied or dissatisfied.

Figure 8 shows that the 57% of respondents who were either ‘very’ or ‘quite’ satisfied with the NHS overall in 2017 selected five main reasons to explain their responses. The majority told us that they were satisfied with the NHS because of the quality of care provided and because the service is free at the point of use. Positive feelings about NHS staff and the range of services available were

selected as reasons for satisfaction by just over two in five, and the length of wait for general practice and hospital appointments was selected by almost a third.

While reasons for satisfaction mainly centred on quality and the underlying structure of the NHS (free at the point of use, with a wide range of services available), reasons for dissatisfaction mainly related to resourcing issues. Figure 9 shows that, among the 29% of respondents who were dissatisfied with the NHS in 2017, the majority put this down to long waiting times, lack of funding or a lack of staff in the NHS. Around a third of dissatisfied people said this was because of government reforms to the health service, and a quarter said their dissatisfaction was due to money being wasted in the NHS. This shows that dissatisfaction was driven by negative views about decisions on resourcing, rather than negative views about the core principles of the NHS.

It is interesting that very few people gave ‘stories in the media’ as a reason for expressing either satisfaction or (in particular) dissatisfaction with the NHS – despite widespread media coverage about pressures on NHS services (see 'Media coverage of the NHS in 2017' box below.). It may be that media stories have an indirect impact on underlying attitudes that is not immediately obvious to the respondent.

The survey has included these additional questions since 2015, which means that changes in responses can now be tracked over time. Figure 10 shows changes in the five most popular reasons for dissatisfaction with the NHS in 2017, over the past three years.

Between 2015 and 2017, the proportion of respondents who were dissatisfied because the government ‘doesn’t spend enough money on the NHS’ increased from 39% to 51% and the proportion who were dissatisfied because there are ‘not enough NHS staff’ increased from 44% to 52%. At the same time, the proportion who were dissatisfied because they felt that ‘money is wasted in the NHS’ decreased from 35% to 25%. This suggests that the increase in dissatisfaction over the past three years (from 23% to 29%) can be partly explained by a view among the public that extra resources are needed for the health service.

There has also been a significant increase over the past three years in the proportion of respondents who are dissatisfied because of ‘government reforms that affect the NHS’ (up from 20% of dissatisfied respondents in 2015 to 32% in 2017).

Media coverage of the NHS in 2017

The 2017 BSA survey took place against a backdrop of significant high-profile media coverage for the NHS, and at a time when the public ranked the NHS as the biggest issue facing the country, reporting their highest level of concern in 15 years.

The year started with a striking image on the front page of the Daily Mirror of a sleeping toddler in A&E lying on two pushed-together chairs. During the same week, the Red Cross said that winter pressures meant the health service was witnessing a ‘humanitarian crisis’.

During the build-up to June’s snap General Election, the subject of social care caused problems for the Conservative Party when their social care manifesto policy was coined by the media and critics as a ‘dementia tax’. For several days after the policy was announced, social care and the debate on care for older people more generally were pushed to the top of the news agenda.

When Britain experienced three terrorist attacks between March and June, praise for the emergency services, including NHS staff, was echoed strongly across the media by victims, politicians, journalists and the general public. From 20 June to 11 July, BBC2 broadcasted 'Hospital', a four-part fly-on-the-wall documentary following the staff of St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, London, with the first episode showing how they responded to the Westminster terrorist attack.

In August, while the survey was being conducted, the number of people waiting for surgery in England topped four million for the first time in 10 years, leading to extensive coverage across print and broadcast media. Calls for increased funding for the NHS have continued to receive regular media coverage.

Conclusion

The BSA survey has now been monitoring public views for half of the 70-year life of the NHS. This data provides its richest insights when viewed over decades, rather than years. Looking at the 2017 data through that long-view lens reminds us that overall NHS satisfaction levels remain higher than they were in the 1990s and early-to-mid-2000s. Nevertheless, the statistically significant fall in satisfaction (and rise in dissatisfaction) in 2017 took net satisfaction to its lowest level since 2007. With an increase over the last few years in the proportion of survey respondents reporting lack of funding as a reason for their dissatisfaction, it seems the public is increasingly aware of the reality of funding pressures that the NHS has experienced over the last seven years. With equally small increases in funding planned over the next few years and NHS performance on key headline measures worsening, it is hard to see the public’s satisfaction with the NHS improving in the near future.

Footnotes

1. The 2017 BSA survey questions on satisfaction with the NHS reported here were jointly sponsored by the Nuffield Trust and The King’s Fund. (Back to text)

2. If a difference or change is statistically significant at 95%, we can be 95% confident that the survey result reflects a real change or difference in public views, rather than being down to chance. Where a difference or change is not statistically significant, we cannot be confident that it reflects a real change or difference in public views. (Back to text)

Methodology

Sample and approach

The 2017 survey consisted of 3,988 interviews with a representative sample of adults in England, Scotland and Wales. Addresses are selected at random and visited by one of NatCen Social Research’s interviewers. After selecting (again at random) one adult (aged 18 and over) at the address, the interviewer carries out an hour-long interview. The participant answers most questions by selecting an answer from a set of cards.

The sample size for the overall NHS satisfaction question reported here was 3,004 in 2017; for questions about satisfaction with other NHS services the sample size was 1,002. The data is weighted to correct for the unequal probabilities of selection, and for biases caused by differential non-response. The weighted sample is calibrated to match the population in terms of age,

sex and region. The margin of error in 2017 for the health care questions was around +/–1.4 to 3.7 percentage points.

The majority of fieldwork for the 2017 survey was conducted between July and October, with a small number of interviews taking place in November.

Topics

The topics covered by the survey change from year to year, depending on the identities and interests of its funders. Some questions are asked every year, some every couple of years and some less frequently.

Funding

The survey is funded by a range of charitable and government sources, which change from year to year. The survey is led by NatCen Social Research. NatCen carries out research in the fields of social and public policy, uncovering the truth about people’s lives and what they think about the issues that affect them. As an independent, not-for-profit organisation, NatCen focuses its time

and energy on meeting clients’ needs and delivering social research that works for society.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Eleanor Attar Taylor from NatCen for her assistance with data analysis, to Kirsty Ridyard from the Nuffield Trust for her analysis of media stories during the field period and to all of our colleagues at The King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust who provided helpful comments on earlier drafts and helped with the editing, digital content and launch of this report. Most importantly, we would like to thank members of the British public for the time they took to complete this survey and for providing us with this fascinating dataset.

Partners

Suggested citation

-

Figure 6: 'Public satisfaction with NHS and social care services, 2017' was updated to correct an error in the Accident & emergency survey responses. The chart's categories have been re-ordered accordingly.