Since 1993, trends in the numbers of people aged between 16 and 64 saying they were economically inactive – that is, not in work for various reasons – rose by around 11% to a peak of around 9.6 million in 2011. However, by the beginning of 2020 (the three months from December 2019 to February 2020), those numbers had fallen back to 8.4 million – levels similar to the early 1990s.

But from this low, just before the start of the pandemic, things have since reversed, with the numbers of economically inactive rising to 8.8 million by the quarter beginning October 2022.

The main reason for this recent growth in inactivity has been an increase in people reporting long-term sickness, which increased by 357,000 between late 2020 and late 2022.

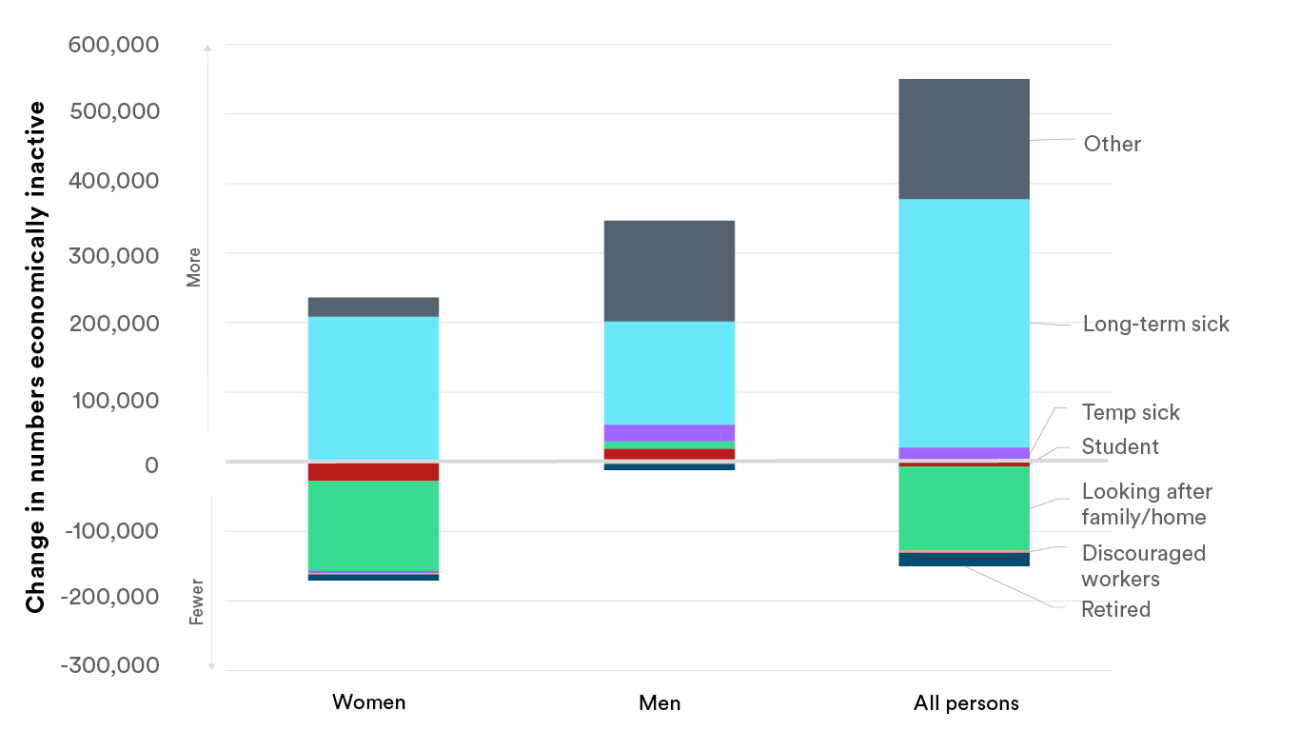

Although most of the net increase in inactivity is attributable to men (333,000 compared to 65,000 for women), the net change conceals differences between men and women in the reasons they gave for being inactive.

In particular, as the chart shows, long-term sickness rose more for women than for men (209,000 vs 148,000), with overall growth in inactivity for women and men combined partially offset by a reduction in women (unlike men) reporting “looking after family or home” as a reason.

While reductions in labour market participation are almost certainly in part associated with the impact and aftermath of the pandemic, for women the rise in long-term sickness as a reason for inactivity pre-dated Covid, starting at the beginning of 2019. For men, however, the increasing trend started later, in the quarter from May to July 2020.

Reducing the number of people who are long-term sick may only be part of the answer to increasing participation in the labour market. As ONS note, around 80% of the growth in the numbers of long-term sick over the last few years have been people previously inactive, but for a different reason. And of those who no longer classified themselves as long-term sick, only 16% returned to employment.

Aside from the labour market, tackling recent rises in long-term sickness will represent a challenge to health services as they grapple with the demands of post-pandemic recovery, and intensify the spotlight on whether the NHS is able to deliver what politicians and the public want.

Suggested citation

Appleby J (2023) “The gender divide in reasons for economic inactivity”, Nuffield Trust chart of the week