Earlier this week there was a sense of panic in the air as a number of hospitals declared ‘major incidents’ and missed their waiting time targets. It’s a response somewhat out of proportion to the scale of the problem – while performance is among the worst it has been in the last decade, it’s still high by international and longer-term historical standards.

What has actually been happening?

A number of explanations of what has been going on have been offered this last week, but they don’t all add up. So let’s start with some facts.

A growth in raw numbers

Between the 2013 and 2014 calendar years, A&E attendance rose 3%. And if we look a bit further back, the total increase since 2011 has been 5%.

There were 14.185 million type 1 attendances (i.e. in major A&E departments) in 2013 compared with 14.631m in 2014 – an additional 446,000 patients a year. That’s the equivalent of around eight extra patients per trust per day in 2014.

This increase in demand is more than what population growth alone can explain, but the NHS has absorbed fluctuations or growth of this sort before. In fact, the numbers in A&E were actually higher during the summer when the four hour performance was a lot higher.

Emergency admissions have risen 5% in the last year and 7% since 2011. The data for ambulance is less up-to-date, but they show a much more significant growth in demand over the last few years.

Data for 111 is only available up to October, but on the Today Programme Professor Keith Willett said that there had been a sudden surge in demand in late December.

There is no data about demand or activity in general practice (!).

Changes in the type of demand

Ageing, the growth of comorbidity, and other long term trends do explain part of the growth. However, this change has been gradual and does not account for the sudden problems that have been experienced in a number of places.

The same is true of some (unproven) ideas about changes in patients’ and their relatives’ attitudes, risk aversion in medicine, etc.

A few hypotheses about where the real problems lie

The health service is complex system in which the interaction between the components are important as changes in any one area. As such, it is very likely that the problems are the result of a number of decisions and policies put in place by the health and social care system, and not any single answer by itself.

We’re convening a group of experts to analyse the issue in the coming weeks (see more information below), and more ideas may arise then. But in the meantime, here is one version of what I think is going on that I would like to test. It’s a cycle so where we start is arbitrary:

- Increased occupancy meets reduced bed numbers: Long-term growth in demand, an ageing population facing more complex conditions combined with bed reductions of 6% since 2010 have increased occupancy rates in the ED. This leads to higher staff stress and, crucially, reduces the resilience of the system making it very prone to small shocks. Lack of trained staff in A&E and acute medicine further reduce the effectiveness of the system to absorb shocks and small variations in flow can tip it into chaos. See more on this in our report on A&E attendances from Quality Watch, a joint programme with the Health Foundation.

- Patients in the wrong places: A rise in admissions from November onwards leads to pressure on the system – it’s within expected limits but enough to cause the system to buckle. Patients start to be placed on the wrong wards. ‘Admit to decide’ approaches are adopted. Patients are moved around and length of stay starts to rise. This further restricts the availability of beds to move patients on, and staff in A&E and ambulances start to be enlisted to care for patients who should be moved on rather than dealing with new ones. Even more chaos ensues, staff go sick and more patients end up in the wrong place.

- GPs with long ‘to do’ lists: In the rush to clear bed spaces, patients may be discharged rapidly to GPs with long ‘to do’ lists. The danger is that these don’t get done, possibly causing a readmission. Or it might just add to the high level of pressure that GPs feel – reducing their capacity to absorb demand from other patients.

- Problems in planning: Seamus McGirr from the NW Commissioning Support Unit pointed out to me that, in many places, the problem is exacerbated by hospitals using averages to plan their physical capacity and staff. This seems logical but is deeply flawed: averages are not a good guide as spare capacity on the days that are quieter cannot really be reused when it’s busier than average. Also it is the capacity of the system in terms of flow that is important not just the numbers of beds or staff.

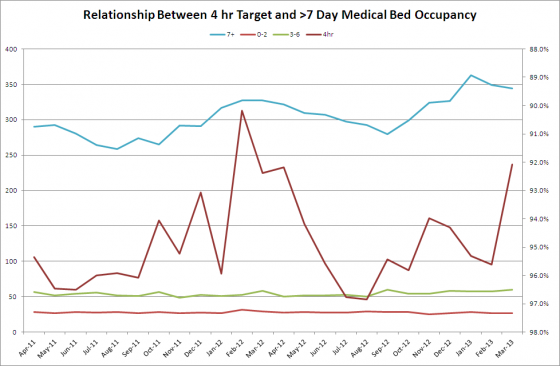

- Patient discharge is often the issue, especially over the Christmas break: Frequent moves, internal frenetic activity and reduced availability in social care mean that discharges drift even further or are done in a hurry. Further problems are caused by restrictions on social care and community services and some anecdotal trends for relatives to be more resistant, particularly where residential care is involved. See Chris Roseavere’s blog on this. Additionally, I am told that over Christmas discharges in a number of hospitals slowed right down. Before Christmas bed closures from norovirus were above last year’s figures and delayed transfers of care were also up. So when things started up again the beds were already quite full. The most significant impact on the problem is the group of patients with extended stays – over seven days and beyond – data from Dr Steve Allder below illustrates this:

- Managing up: Add into this mix a performance management system in which a significant amount of managerial time is wasted in non-value adding reporting upwards. One Chief Operating Officer I spoke to told me that her key person running the hospital spends hours a day doing this. This cannot be right and must, at the very best, get in the way.

- Self-re-enforcing factors: It is likely that a number of the short term actions designed to solve immediate problems make things worse. The performance management system is almost certainly exacerbating the problem rather than helping to fix it.

These are only some of my thoughts based on what I’m hearing. Does it sound right to you? What do you think I’m missing? I’m curious to hear your reactions in the comments below.

Different problems, different solutions

If this is close to being right, then a different approach to solving it is required than shouting at people and insisting they deliver. It requires some serious systems thinking and some head room and space to deal with it.

It also implies that the focus on trying to fix A&E (which undoubtedly has problems) and reduce demand from the generally minor patients may be missing a bigger point about the dynamics of the whole system.