The inequality in women’s maternal health outcomes is sobering. In the UK last year, women of Black ethnic backgrounds were four times more likely than white women to die in childbirth, and Asian women were almost twice as likely. Likewise, women living in the most deprived areas had a maternal mortality rate two-and-a-half times higher than women living in the least deprived areas.

Reducing inequality in maternal mortality is rightfully a concern for NHS England. After reports into the repeated failings of maternity services in England that frequently identify suboptimal staffing levels, among other causes, the need to deliver safer, more personalised and equitable care is evident.

Consequently, reducing inequality in maternal health care has been a key aim of NHS England and NHS Improvement’s CORE20PLUS5 – the policy that aims to reduce health care inequalities – which was published in November 2021. Its first area of attention is to ensure continuity of carer (which means seeing the same midwife or midwifery team throughout pregnancy and the postnatal period) for women from Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities and from the most deprived areas.

It is widely accepted that seeing the same midwife can contribute to building a supportive and trusted relationship between mother and care-giver, leading to better outcomes for the mother and baby. The NHS Long Term Plan states that 75% of women from Black, Asian and other ethnic minorities and the most deprived areas should receive continuity of carer by 2024, but the actual rate of women receiving this type of care has never been close to the target. In this blog, we assess the current progress in delivering continuity of carer for women from the most deprived areas as well as for women from Black and Asian ethnic backgrounds, and consider why inequalities persist.

There are, however, significant challenges to its implementation. In September last year, NHS England told NHS trusts that there will no longer be a target date to deliver continuity of carer until sufficient staffing levels can be demonstrated, while prioritising delivery of care for ethnic minority and the most deprived women.

The removal of targets may be understandable, but it raises important questions about the implications for addressing inequality in women’s experiences of maternity care and achieving the wider aims of CORE20PLUS5.

How does the rate of women seeing the same midwife differ by deprivation?

Although the national average of women receiving continuity of carer has stayed relatively stable at around 22% since June 2021, there has been a significant percentage fall for women from the most deprived areas – by 14 percentage points to May this year from its peak in September 2021. The introduction of the target date in November 2021 clearly had no effect on increasing continuity for women living in the most deprived areas, and with such low rates of women receiving this type of care, the target date was considered unattainable and was removed in September last year.

In May last year, the rate of continuity of carer for women from the least deprived areas overtook that of women from the most deprived areas and has remained so. It may be expected to see a larger proportion of women from the least deprived areas receive continuity of carer, as evidence suggests wealthier women are less likely to struggle with system barriers and ask for the care they want. But this direction should be a cause for concern given the aims of the policy. As of May this year, there was minimal difference between women living in the most and least deprived areas, but women in the most deprived areas are still worse off and have the smallest proportion receiving continuity of carer.

How does the rate of women seeing the same midwife differ by ethnicity?

NHS England’s maternity data publishes continuity of carer rates by ethnicity at the level of three large collective groups for white women, women of Black, Asian and other ethnic minorities, and women of other smaller ethnic minorities. It is not disaggregated any further.

We recognise that grouping several ethnicities together can obscure real differences in experience of care among a diverse group of women and limits our analysis presented here. The data limitations should be considered when looking at the below chart and analyses.

The change over time by ethnicity has not been quite as dramatic but we do see a similar pattern as shown for deprivation above. Overall, the percentages of women from Black and Asian and other ethnicities receiving continuity of carer have generally been above the national average of 22%, while white women have been slightly below.

However, there has been a decline in the rate of continuity of carer for Black, Asian and other ethnic minority women, from 28% in August 2021 to 23% in September last year when the target date was scrapped. While the rate for Black, Asian and other ethnic minority women has since picked up, May saw the lowest rate this year with only one in five women seeing the same midwife.

Why do these inequalities persist?

Ensuring safe staffing levels is a critical factor in providing continuity of carer. Since 2010, the number of full-time equivalent midwives has increased by 12%, while the number of births has fallen by 16%. Meanwhile, the number of more complex pregnancies has also risen. Births by women aged 40 or over have increased by 13% in the last decade, while obesity prevalence in pregnant women is at 26% (2022/23). In particular, high sickness absence rates in midwives have also exacerbated pressures on services. All these factors make delivering continuity of carer difficult.

So, what exactly does safe staffing in maternity care look like?

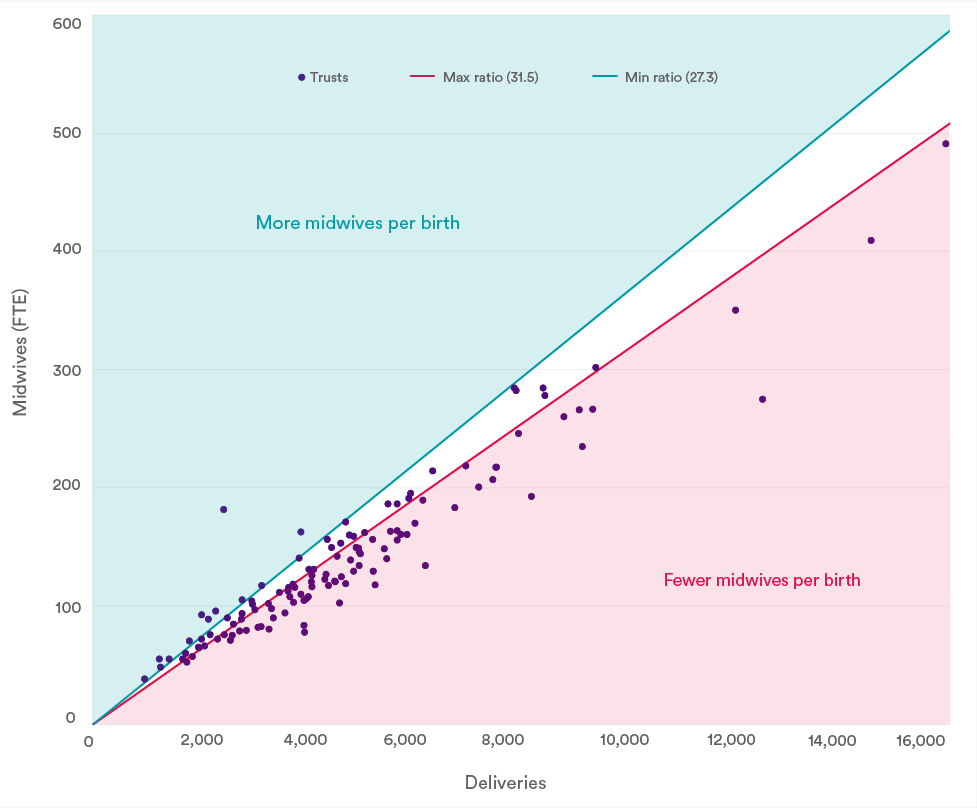

One indication of safe staffing can be derived from Birthrate Plus, the national tool that estimates the safe number of midwives needed in each trust based on a midwife-to-birth ratio, accounting for caveats such as absence rates and complex pregnancies. The tool suggests an average ratio of 29.5 births per midwife per year, with a safe range between 27.3 and 31.5.

In 2021/22, accounting for a 21% absence rate as expected by Birthrate Plus, 75 (61%) trusts fell below the minimum level of safe staffing, evidencing the extent of staffing pressures in maternity services. This chart shows just one estimation of the number of midwives required and does not account for local factors such as complex pregnancies and staff mix, so the true midwife-to-delivery ratio is likely to fall below this level.

It is important to appreciate that continuity of carer is a resource-intensive model of care that requires more than just an increase in midwives, but a system that supports midwives to deliver care in this way.

Where does this leave progress in addressing inequality in women’s experiences of care?

Staffing pressures have real implications on providing good quality care to women, including on delivering continuity of carer, especially for women living in the most deprived areas and women of Black, Asian and other ethnic minorities. As we have shown, only a minority of women are able to see the same midwife throughout their pregnancy. That is an average of only 17% of women from the most deprived areas and only 22% of Black, Asian and other ethnic minority women seeing the same midwife – both well below the 75% target. Continuity of carer may be just one part of delivering maternity care, but the fact that its implementation has stalled because of a lack of staffing shows once again the persistent issue of suboptimal staffing, which will only widen inequality and put women and babies at risk.

We also recognise that data on racial and ethnic inequalities needs improving. Data should be disaggregated at individual level rather than referring collectively to a large and diverse group of women. This can obscure real differences in experiences and limits our knowledge of progress towards equitable care, especially for example when we know maternal outcomes can be very different between Black and Asian women.

Targets may be one way to achieve progress, but they are not without their limitations. It is clear that the target was unattainable with a lack of midwives to action it, even for specific groups of women. But reducing inequalities in maternal health remains a pressing issue that requires clear policy action. Continued staffing pressures risk undermining the broader aims of addressing inequality, which will have significant implications for quality of care. While it is understandable that the target date was scrapped, we must not lose momentum in eradicating inequality in maternal health care.

About this data

The data published in the Maternity Services Data Set (MSDS) are experimental statistics and therefore should be treated with caution. Due to the introduction of MSDS.v.2, an updated version of the maternity services dataset, in April 2019, data quality and coverage will be variable.

Rate of women on a continuity of carer pathway by 28 weeks

This measures the percentage of women placed on a continuity of care pathway by the 28-week antenatal appointment and is measured at 29 weeks (published as part of NHS Monthly Maternity Measures statistics).

Denominator: All women who have reached 29 weeks' gestation in each month and who have not been discharged.

Numerator: Women out of the denominator who have had a formal antenatal booking appointment by 29 weeks' gestation, an antenatal care plan is in place, and there is an indication the woman is on a continuity of carer pathway where there is a named lead midwife and/or team.

This indicator is measured at 29 weeks to allow for possible appointment delays. Women who are placed on a continuity of carer pathway after 29 weeks' gestation are not included. Similarly, women placed on a pathway before 29 weeks' gestation but there are no data identifying the midwife or team are not included.

Ethnicity disaggregation includes only groups for white women, women of Black, Asian and other ethnic minority women, and women of other ethnicities including other Chinese minorities. See NHS Data Dictionary for ethnic categories.

Deprivation is based on the postcode of the mother’s usual address. The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) is used to rank neighbourhoods by level of deprivation into 10 equal groups called deciles.

Deliveries/births-to-midwife ratios

The chart included in this blog is updated analysis on staff-to-birth ratios from the National Audit Office’s (NAO) Maternity services in England 2013 report.

Delivery/births-to-midwife ratios are calculated by dividing the number of annual deliveries by the average number of midwives taken across the year. An average is taken because staff numbers naturally fluctuate throughout the year.

According to Birthrate Plus, a ratio greater than 31.5 might indicate there are too few midwives for the number of deliveries.

Birth-to-midwife ratios as calculated by Birthrate Plus are unique for each trust. Trusts' ratios are dependent on case mix, demographics, models of care, and skill mix. The data presented here is an estimation accounting for average absence rate expected by Birthrate Plus only, and therefore should be used indicatively. The actual ratios are not publicly available.

Suggested citation

Dodsworth E (2023) “Inequalities in midwifery continuity of care during pregnancy" QualityWatch: Nuffield Trust and Health Foundation.