Clearly delighted at having some good news to share about the NHS, the government in a recent press release announced the recruitment of 29,000 extra staff into general practice through the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS). This is 12% more than the target of 26,000 set in 2019, and has been achieved one year ahead of schedule.

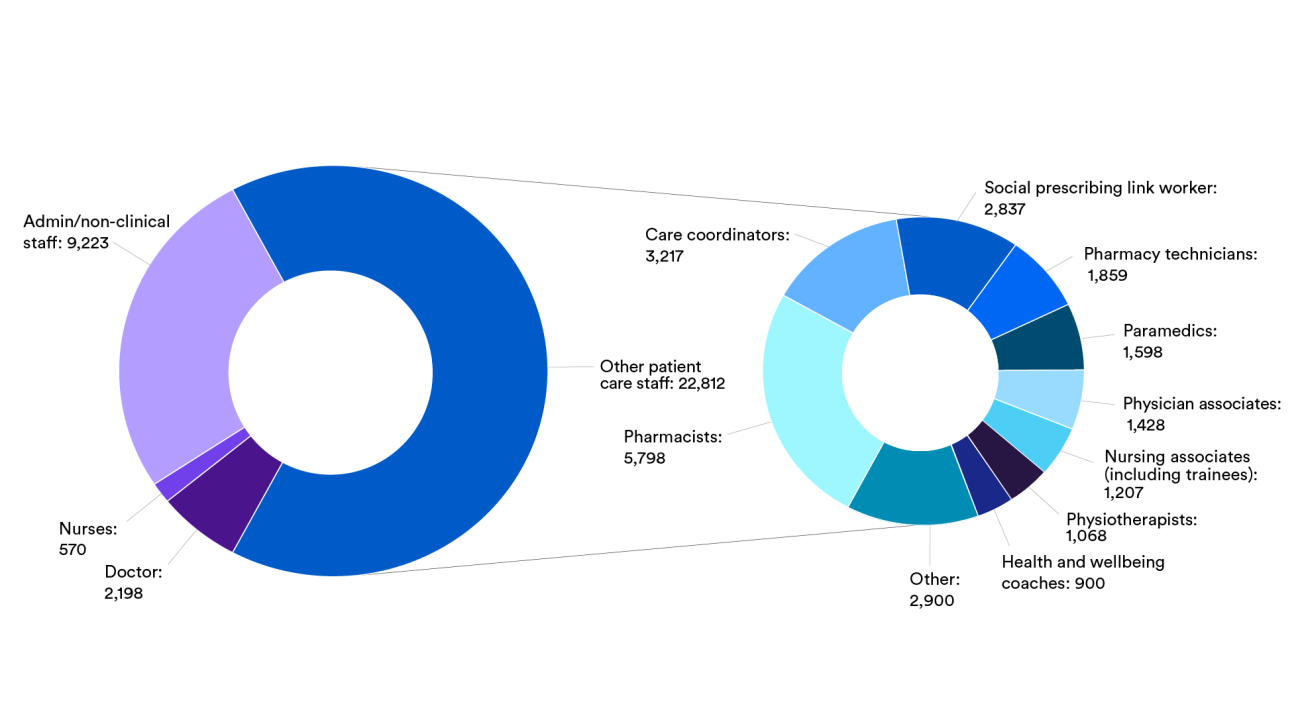

But if you dig into the detail of the general practice workforce data released last month and summarised in the chart below, you see that approximately one-third of the new roles are a non-clinical mix of receptionists, care coordinators, social prescribing link workers and managers. Pharmacists are the largest additional clinical group, followed by paramedics, physiotherapists, pharmacy technicians and others.

In one sense, the headline figures are indeed good. With huge public frustration about access to general practice and the No 10 press release on GP recovery headlining plans to “smash the 8am rush”, extra receptionists (along with universal cloud telephony announced in the recovery plan) will certainly help.

Care navigators can manage demand for appointments by steering patients with minor problems to alternative services. Care coordinators, who support patients with complex needs using multiple services, can improve patient and carer experience. And social prescribers can help to address the social determinants of poor health that are brought to general practice.

The need for more clinically trained staff

But the underlying problem of the mismatch between demand and clinical capacity, which has been well described and is further evidenced by the growth in patients paying for private GPs, cannot be fully resolved with non-clinical roles. There is no getting away from the fact that we still need to recruit more GPs and other clinically trained staff in order to meet patient needs.

And despite the substantial increase in practice staff numbers, public satisfaction with access has continued to fall and the number of patients seeing a private GP is increasing fast, so questions remain about how well the mix of new staff in general practice is able to address the varied clinical needs and service quality expectations of registered patients and restore public trust in the service. And looking beyond the numbers, are the necessary organisational changes and support mechanisms in place to enable those in the new roles to fulfil their potential.

There is no simple formula for calculating the number or type of appointments or clinicians needed for a registered patient list. The Care Quality Commission acknowledges this, noting that practices must design access according to local population characteristics (such as age, deprivation and ethnicity) and available staff.

Where new clinical roles are introduced into well-designed clinical pathways and triage systems overseen by experienced clinicians, they are helping to restore the balance between need and capacity.

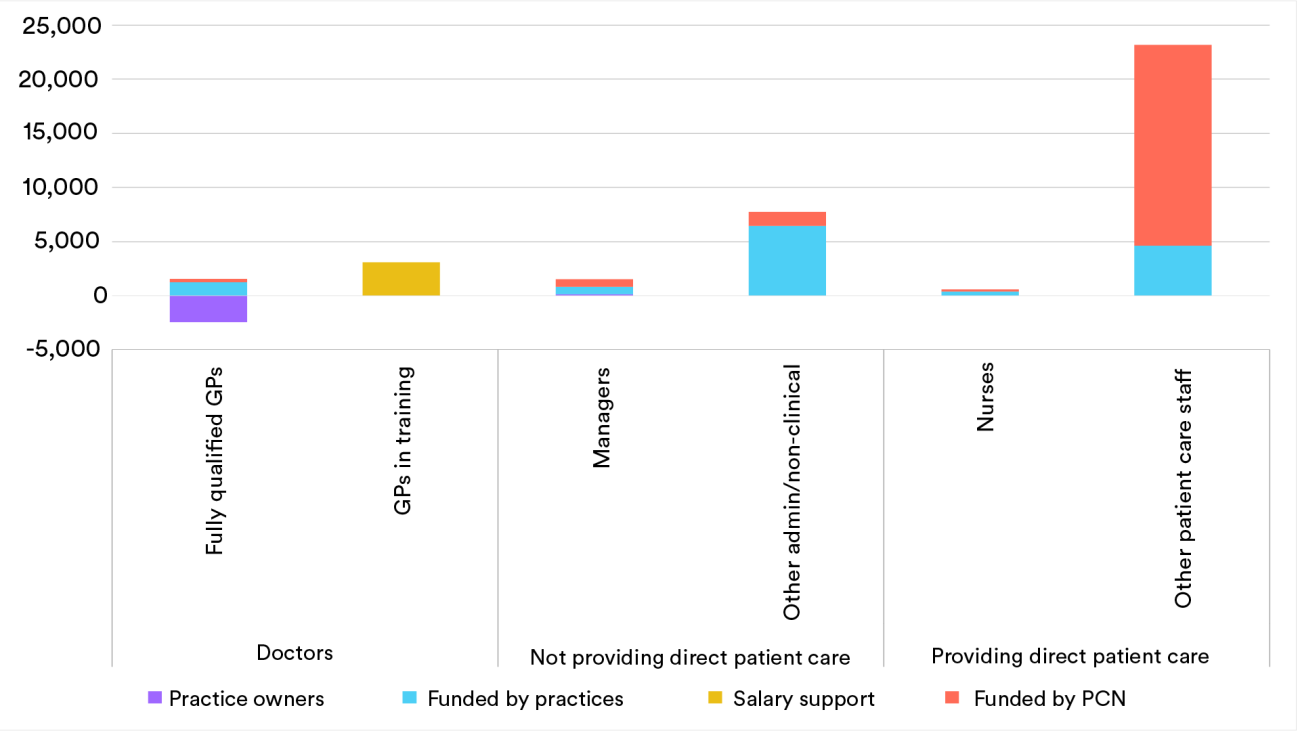

But here lies part of the problem. High-quality triage systems are difficult to set up and tend to be organised and run within practices, while the majority of roles through the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme were funded and recruited through primary care networks (PCNs) as shown in this chart.

Clear purpose and support

A recent study of introducing additional roles into PCNs concluded that networks tend to lack a shared vision for how to integrate them effectively into the day-to-day work of practices. They work when they are introduced with clear purpose, with attention to the cultural change needed for multi-professional working and with support for practices to redesign their services to accommodate the new roles. The study also highlighted the support needed for staff from the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme – through supervision and mentoring to build clinical skills and confidence, and also in terms of team building and in creating a sense of belonging.

Whichever additional roles are introduced, the implementation challenges described above must be addressed urgently if we are to maximise the benefits for patients and staff from the rapid growth in the GP workforce.

With everyone in general practice working under intense pressure, this will not be easy, but the recent GP access recovery plan may offer some of the focus and building blocks needed. The requirement to introduce triage arrangements to prioritise requests for appointments is a starting point for clarifying the purpose of different roles within and between practices – for redesigning clinical pathways and for strengthening multi-professional working. And there are resources available through the recovery plan to support these developments.

Some practices will be offered practical support to redesign services and every practice will receive funds to free up time for this work, although the resources offered may not be enough for the scale of work needed.

In areas with a GP federation – a large-scale organisation typically owned and run by GP practices to which it provides additional services and organisational support – the federation may be best placed to do the heavy lifting of recruiting, inducting, training and supporting new roles. Where there is no federation, this work will fall on the limited leadership and management capacity of PCNs and practices.

We are at a critical point in ensuring that the expanded primary care workforce helps to sustain general practice in ways that meet clinical need, and also work well for patients and staff. The design and implementation challenge is huge. Practices and PCNs will need to be very honest about what they can realistically achieve without extra external support for designing and implementing these new roles. They will need to buy this in if necessary, and should expect tolerance, goodwill and support from politicians, patients and local health systems alike as they focus their efforts on making the new roles work.

Suggested citation

Rosen R and Palmer W (2023) “More staff in general practice, but is the emerging mix of roles what’s needed?”, Nuffield Trust blog