There’s been a bit of noise about NHS treatment waiting list statistics lately – many commentators expected that the waiting list would exceed three million people in April. There’s no particular significance to the figure – it’s not a target – but is a big, round number that grabs headlines. And 11 months out from an election, that means it’s politically important.

It’s not just about size

It’s important to bear in mind that an increase in the number of people waiting isn’t necessarily an indication of a decline in the quality of service. The key thing is how long people have to wait for treatment.

If the list is long, but people are being treated quickly, the size of the list isn’t important. This is something the Labour party recognised in 1997 - having swept to power on a popular pledge to reduce waiting lists, they realised this was a poorer measure than waiting times, so switched it.

Ultimately, the published data last week showed that the number had stayed just under the magic three million – although there is currently some dispute about missing data – and so the statistics did not receive much press attention.

Waiting times on the increase

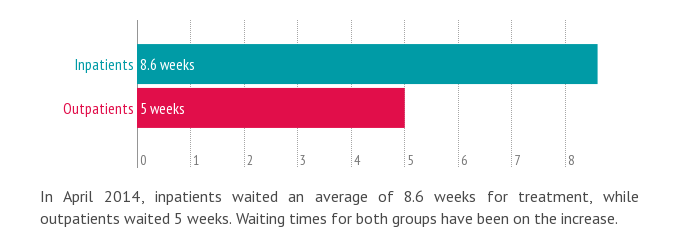

But what’s been happening to the length of time people wait for treatment? There are many ways to measure how long people are waiting – but for treatment waiting times, we often use the median. The median gives us the middle value, with half the people waiting a longer time and half the people waiting a shorter time.

We use the median mainly because it is less affected by extreme numbers. For example, a small number of people waiting a very long time for treatment will have little effect on the median. Median waits for treatment have been on the increase for inpatients and outpatients. In April this was just over 8 and a half weeks for inpatients, and 5 weeks for inpatients.

The 18 week standard

Perhaps more significantly, the percentage of inpatients waiting the longest – more than 18 weeks – for treatment had been on the rise. The NHS standard is that no more than 10% of inpatients should wait longer than 18 weeks. In February and March this target was breached and April this was just hit, with 10.0% of inpatients waiting more than 18 weeks for treatment – to quantify that, this means that in April roughly 30,000 people waited more than 18 weeks.

Do thresholds help?

This leaves two interesting questions. First, is how important is it to achieve a particular threshold value and is it that much better to just hit a ‘target’ than to just miss it?

In terms of the way the system operates it is unlikely to make much difference whether 2.9 or 3.1 million people are waiting, or whether 89% or 91% of people wait less than 18 weeks. What’s more important is to understand the trend, and waiting lists are a bit unusual in this respect as performance in one month can depend on what happened in the month(s) before. People left on the list still need to be treated, so low performance in one month means there are even more people to be treated in the following month – making it harder to achieve the target. This can easily become a vicious circle.

A blip or a trend?

Until August 2013 the treatment waiting list followed a clear seasonal trend, but this winter the list didn’t shrink as expected.

And that brings us to the second question: are these recent changes a temporary blip or a longer term trend? That’s much harder to know. Until August 2013, the treatment waiting list has followed a very clear seasonal trend, with the list being longer in the summer and shorter in the winter. But this winter the list didn’t shrink as expected and has remained at just under three million. It’s currently unclear whether this figure will remain consistent or whether we’ll see additional growth again in the summer.

To try and manage the potential summer growth it was announced last week that the Department of Health would provide an additional £250 million to help the NHS clear treatment waiting lists. Providers will only be able to access the money once they’ve provided detailed plans of how it will be used, but it looks likely the additional money will be spent on providing treatments at night and at weekends and also to train staff on recording accurate treatment waiting times.

We’ll have to keep monitoring to see if this extra money will help ease the waiting list pressures, but you can be sure if performance on waiting lists does not improve, by the NHS missing targets or allowing the waiting list to continue growing, they’ll be receiving much more attention from the media in the coming months.