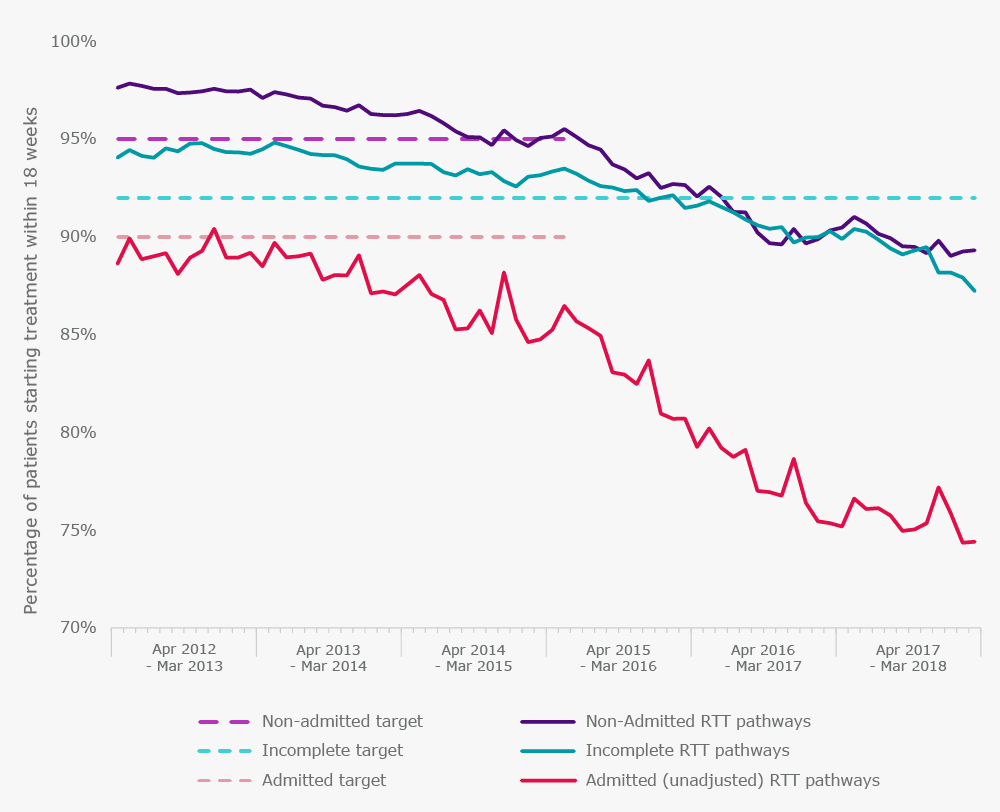

The NHS Constitution sets out that patients have a legal right to “start consultant-led non-emergency treatment within a maximum of 18 weeks of a GP referral”. The operational standard is that the time waited must be 18 weeks or less for at least 92% of patients who are waiting to start treatment (referred to as ‘incomplete pathways’). Performance against this target has worsened over the last couple of years, and the target was last met in February 2016.

In March 2018, only 87% of patients had a treatment waiting time of less than 18 weeks.

How did we get here?

Treatment waiting time targets were not always this simple. There was previously a 90% target for patients who required admission to hospital and a 95% target for non-admitted patients. As waiting times were only counted at the time when a patient actually started treatment, hospitals were penalised and fined for treating patients that had waited for longer than 18 weeks. Where was the incentive to treat the ‘long-waiters’ who had already surpassed the waiting time target?

The ‘incomplete’ target, introduced in 2012, measures all patients still waiting at the end of each month. It therefore takes into account every single patient on the waiting list [1]. In advance of the introduction of this standard, the number of people waiting longer than 18 weeks decreased by over 100,000.

In June 2015, national Medical Director Sir Bruce Keogh wrote to the Chief Executive of NHS England recommending the removal of the admitted and non-admitted measures as soon as practically possible. He said that using the incomplete standard as the only measure would “reduce tick-box bureaucracy and expose hidden waits” and “ensure the NHS concentrates on treating all patients as quickly as possible”. It was “absurd”, he said, “to find ourselves in a situation where we had to suspend our own waiting time targets to do what is right for patients”.

The admitted and non-admitted targets were abolished, but performance across all pathways continued to decline.

Figure 1. Performance against the 18-week referral to treatment target

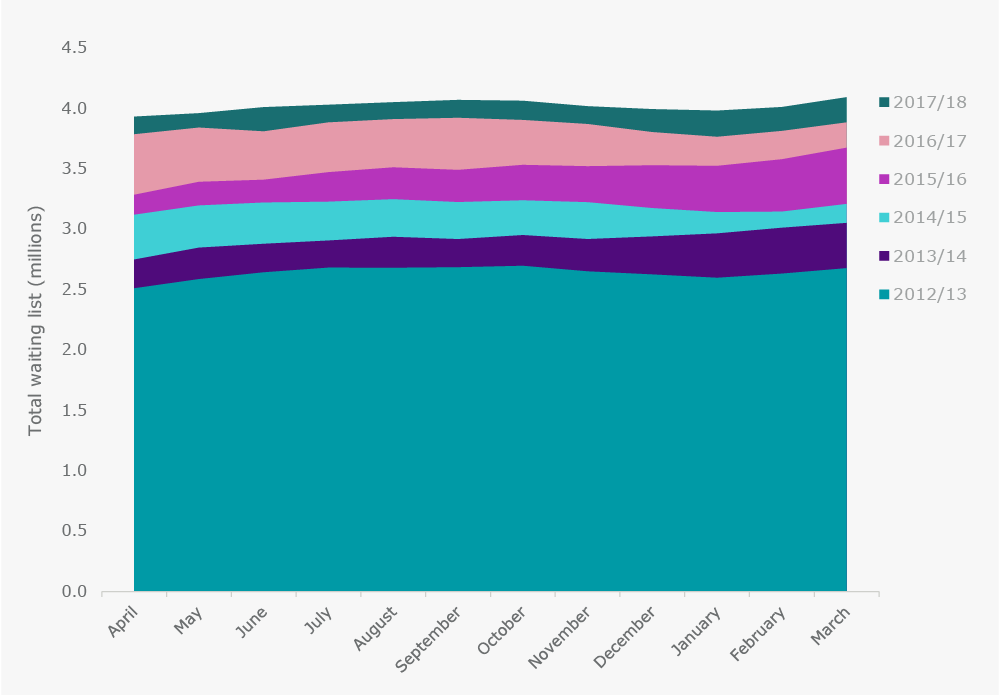

But it’s not just performance against the targets which have deteriorated in recent years. The total waiting list has been growing since 2012, and we now have a waiting list that exceeds 4 million. Between August 2007 and January 2009 the waiting list was reduced significantly from 4.2 million to 2.3 million. Unfortunately, these improvements have now been reversed, and we are now almost back to where we started. While remembering that these figures relate to the number of referrals and not patients (as some patients are referred for more than one treatment), it is clear that NHS resources are failing to keep up with the growing demand for services.

Figure 2. Total waiting list (millions)

The bigger picture

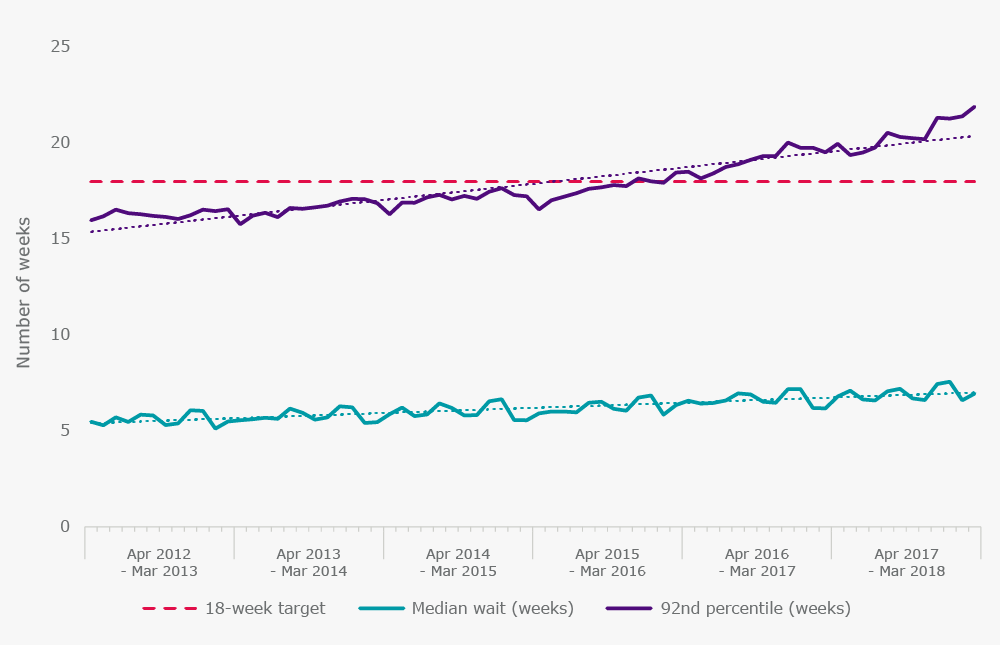

It is easy, though, to become fixated on performance against targets, and to lose sight of how long patients are actually waiting. Figure 3 shows that the median treatment waiting time has increased over the last five years by about 1½ weeks. The 92nd percentile of number of weeks waited (which must equal 18 weeks if the incomplete target is to be met) increased by 5½ weeks, from 16½ weeks in March 2013 to 22 weeks in March 2018. This is extremely worrying as it indicates that patients who are waiting the longest for treatment are being affected disproportionately.

Figure 3. Number of weeks that patients are waiting to start treatment

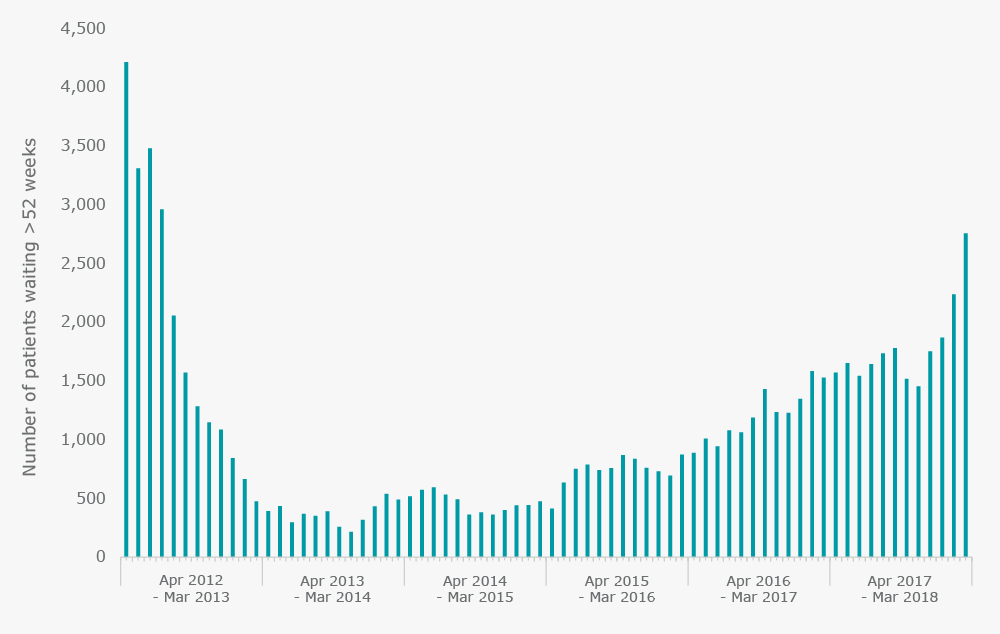

In fact, the number of people waiting longer than 52 weeks to start treatment has been increasing since 2013. In March 2018, 2,755 people had been waiting for longer than a year, the highest number since July 2012. This is despite the government’s emphasis on a zero tolerance approach to year-long waits. Waiting over a year to start routine consultant-led treatment can have devastating consequences on an individual’s health and overall quality of life.

Perverse incentives

Unfortunately, this impact could have been foreseen, as it is well known that the introduction of any form of target can lead to distortion in a system. The problem is that, in health care, the consequences for patients can be severe. In a speech given by Jeremy Hunt, Secretary of State for Health, in August 2014, he acknowledged that waiting time targets can have unintended consequences:

"When the NHS started measuring performance against the 18 week target in 2007, something perverse happened. If faced with a choice between treating a patient who had missed the 18 week target or someone who had not yet reached it, the incentive was to treat the person who had not yet missed the target rather than someone who had – because that would help the performance statistics, whereas dealing with the long waiter would not. So a target intended to do the right thing ended up incentivising precisely the wrong thing.”

He announced an ambition to reduce the number of people waiting for more than a year to be “as close to zero as possible”. Figure 4 shows that the reported number of long-waiters has continued to rise.

Figure 4. Reported number of people waiting more than 52 weeks to start treatment

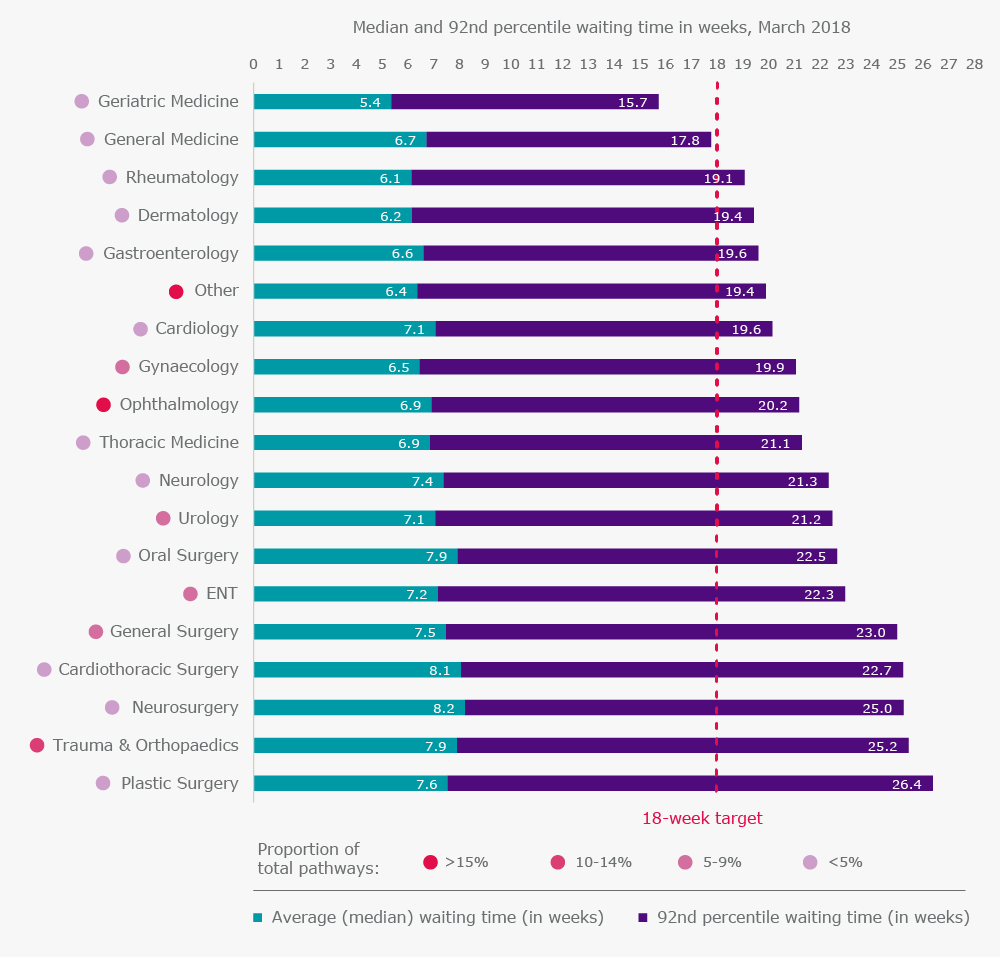

The 18-week target is not only expected to be met across hospital trusts and the NHS as a whole, but across all services and specialties. However, Figure 5 shows that the average person waiting for a neurosurgical procedure can expect to wait almost three weeks longer than a patient waiting for geriatric care; there are differences in waiting times between specialties. Notably, the plastic surgery, neurosurgery, cardiothoracic surgery and trauma and orthopaedic specialties are furthest from meeting the 18-week target. The 92nd percentile for plastic surgery reached almost 26½ weeks in March 2018, and this may include patients who are awaiting life-changing operations such as reconstruction following mastectomy for breast cancer. The waiting times for trauma and orthopaedic patients are particularly significant, since they make up 12% of total referral pathways.

Figure 5. Treatment waiting times by specialty

Delaying the problem

However, these figures should not be viewed in isolation. Over the same time period, performance against the four-hour A&E target and two-month cancer treatment target had plummeted. The government decided to prioritise patients requiring emergency and time-critical treatments, and rightly so. Thus, in the government’s mandate to NHS England for 2018-19 the 18-week and 52-week targets were both pushed back to ‘overall 2020 goals’ – technically breaching the legal commitment set out in the NHS Constitution.

Further to this, the NHS National Emergency Pressures Panel recommended that hospitals defer all non-urgent inpatient elective care for the month of January 2018 in order to help hospitals deal with the sustained pressure over the winter period. Elective admissions to hospital decreased for the months of January and February, although the full impact of this national recommendation on local decisions remains unclear.

The joint NHS England/NHS Improvement guidance which sets out the expectations for commissioners and providers in updating their operational plans for 2018/19 makes no reference to the 18-week target at all. Instead, it states that “commissioners and providers should plan on the basis that their [treatment] waiting list, measured as the number of patients on an incomplete pathway, will be no higher in March 2019 than in March 2018”.

The dangers of making the treatment waiting list a target are obvious – providers may be more inclined to treat the simpler, less complex patients first as they have shorter turnaround times. The second goal, that “numbers nationally of patients waiting more than 52 weeks for treatment should be halved by March 2019” is in itself a good target for patients. However, it still indicates that some patients will be waiting for extremely long periods of time to start their treatment. Alongside these deferred targets, financial penalties for both the 18-week and 52-week treatment waiting time targets were largely abolished in 2017.

A long-term solution?

Within the NHS’s resource-constrained environment, what is likely to happen next? Firstly, waiting times will increase as clinicians will treat the most urgent patients first and the competing demands of managers will mean that other targets such as the four-hour A&E target will be prioritised. Secondly, by deferring the targets and removing the financial penalties, hospitals will have the opportunity to move away from managing the target to improving patient scheduling based on need. Lastly, the long-term effect will be that the waiting list will increase and increase (including the number of people waiting over a year) to such an extent that, eventually, a more radical intervention may be required to address the backlog.

It is clear that this process of deferring targets is not sustainable for the long term. The introduction of the 92% incomplete target was inherently a good thing, as it aimed to reduce the treatment waiting time for all patients. But within the overstretched system in which the NHS is currently operating, patients will increasingly have to wait longer to be treated as there are simply not enough resources and not enough staff.

With the NHS’s 70th birthday fast approaching, and the announcement from the Prime Minister that the NHS will receive a funding boost later this year, will this be enough to curb the problem of treatment waiting times? The future of the NHS may depend on it.

For more information about treatment waiting times, please see our QualityWatch indicator. We also analyse data on a monthly basis in our Combined Performance Summary as data is released by NHS England.

[1] Every single patient, except patients who are referred to one of the six hospital trusts which do not submit referral to treatment pathway data.

Data source: NHS England, consultant-led referral to treatment waiting times.