Following years of local authority budget cuts, the English social care system is struggling to provide sufficient care for those who need it. Increasing numbers are forced to self-fund, while others go without. The impact of the social care crisis is also being felt in the NHS, with many people unable to leave hospital as they wait for social care to be put in place. Projections suggest that by 2019/20, social care will be facing a funding shortfall of £2.5 billion (Nuffield Trust and others, 2017). If migration is halted following Brexit, social care faces a shortfall of 70,000 workers by 2025/26 (Dayan, 2017).

While pressures in social care are not a new problem, there is widespread recognition that it is an increasingly pressing priority. A forthcoming green paper is expected to lay the foundations for developing a new system of funding and provision. It is in this context that the Nuffield Trust went to Japan, to consider what lessons may be drawn from the introduction of its comprehensive long-term care system.

Japan’s social care system

Japan introduced a long-term care insurance (LTCI) system in 2000 which established new models of funding and delivery, and endeavoured to create a positive vision of ageing. In the 1990s, as a country with a rapidly ageing population, a stagnating economy and decreasing capacity for families to take care of older relatives following high numbers of women joining the workforce, it faced an uncertain future. Health care costs were rising sharply, partly as a consequence of a shortage in affordable care provision.

Part social insurance, part taxation and part co-payment model, the new system aims to provide comprehensive and holistic care according to need. Over time, the design of the system successfully created a competitive provider market and facilitated a wholesale shift in care responsibilities, from families and individuals to society as a whole.

Lessons for England

Although the specifics of the Japanese funding and delivery model may not be suitable for the English context, there are a number of important lessons England can learn from Japan’s experience:

- England has so far failed to gain public buy-in or sufficient cross-party support to implement any previous proposals for reform. By making the initial service offer generous, mandating financial contributions from the age of 40 (when most people would see the benefits of the system for their ageing parents), and embedding the principles of fairness and transparency through national eligibility criteria, the Japanese government was able to gain public support and buy-in. However, this did take time. The government in England should be realistic about how much time is likely to be required to ensure genuinely informed public debate is possible. Implementation of any new system should be viewed as a long-term process.

- Intended as a 'living system', LTCI has a high degree of central control with in-built mechanisms for controlling demand and shaping provision. By reviewing the system at three-year intervals, the Japanese government is able to adjust national levers in order to control expenditure and incentivise (or discourage) certain types of provision. In exploring new proposals, the government in England should consider building in flexibility to ensure that the system is able to adapt to changing circumstances and afford some control over expenditure.

- Embedded at the heart of the LTCI system is the care manager, who supports individuals to create care plans that fulfil their needs within an assigned notional monthly budget. Although the roles of care and case managers exist in health and social care in England, there is no single role definition and they demonstrate variable levels of effectiveness. Creating a role that is consistent across the country would help to offer support and clarity about expectations to those navigating the system and to health and care providers.

- As part of the implementation of LTCI, Japan has sought to embed a positive vision of ageing, where older people are supported by wider communities to remain independent and active in society. By investing in prevention and in community resources, Japan is creating supportive communities that seek to maintain wellness and reduce social isolation in order to prevent or delay the need for state-funded services. Although these services have not yet been independently evaluated, the approach contrasts with the English situation where, despite rhetoric regarding the value of prevention in the 2014 Care Act, financial realities have seen local authorities increasingly make cuts to preventative services in order to direct scarce resources to those most in need.

Learning from Japan’s challenges

Although there are many lessons for us to take away from the Japanese system, there are also cautionary tales. Despite impressive successes in implementing comprehensive long-term care services for 6 million eligible people, the Japanese system is now under significant pressure as a result of its ageing population and shrinking workforce. So far, it has managed to sustain the

system by increasing insurance premiums and user co-payments, but it is not clear whether this approach will be sustainable in the long term. Its depression of provider fees has kept wages low and, as is the case in England, many care workers have left the sector to enter other more lucrative industries. With no history of immigration, Japan has struggled to address this looming crisis. In designing a future system for England, there needs to be a realistic assessment of likely need and the corresponding workforce requirements. In the wake of Brexit, a workable strategy for filling rising numbers of vacancies will be of particular importance. It is crucial that workforce issues are not addressed in isolation and that any reform of social care funding is undertaken in conjunction with a review of workforce.

Conclusion

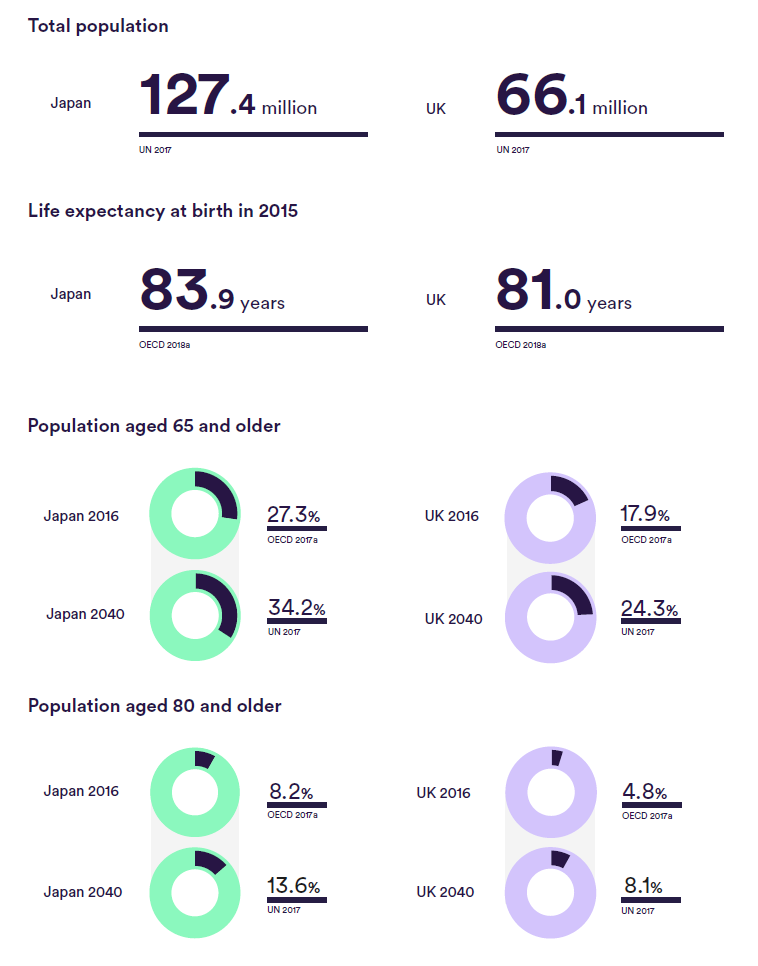

England, like Japan, faces a very challenging future as both countries grapple with the growing needs of a rapidly expanding older population. It could be argued that England is currently in the situation Japan was in in the mid-1990s, where there was growing consensus that radical reform was necessary. The 2018 green paper represents an opportunity to grasp the thorny issue of social care and to design a viable solution that has so far proved elusive. It will be important that all avenues are explored in arriving at a solution and that, importantly, the debate is taken out of the febrile political environment to allow for informed and genuine public discourse. It will also be essential that the green paper doesn’t look at funding options in isolation but that it also

considers the wider delivery system and how it interacts with the NHS, and that it has a particular focus on workforce.

As our government embarks upon its next attempt to grapple with the issues within our own system, it will be of utmost importance that we continue to study the experiences and lessons of those countries that are a few steps ahead. Japan is one of a number of countries that have demonstrated that it is possible to achieve fundamental reform. It is our hope that, through consultation and engagement, the green paper will be a significant step on the journey to a solution that is clear, appropriate, equitable and sustainable.

References cited

- Dayan M (2017) General Election 2017: getting a Brexit deal that works for the NHS. Nuffield Trust, London

- Nuffield Trust, the Health Foundation and The King’s Fund (2017) The Autumn Budget: joint statement on health and social care.

Download the report for a full list of references cited in the main text.

Suggested citation

Curry N, Castle-Clarke S and Hemmings N (2018) What can England learn from the long-term care system in Japan? Research report, Nuffield Trust