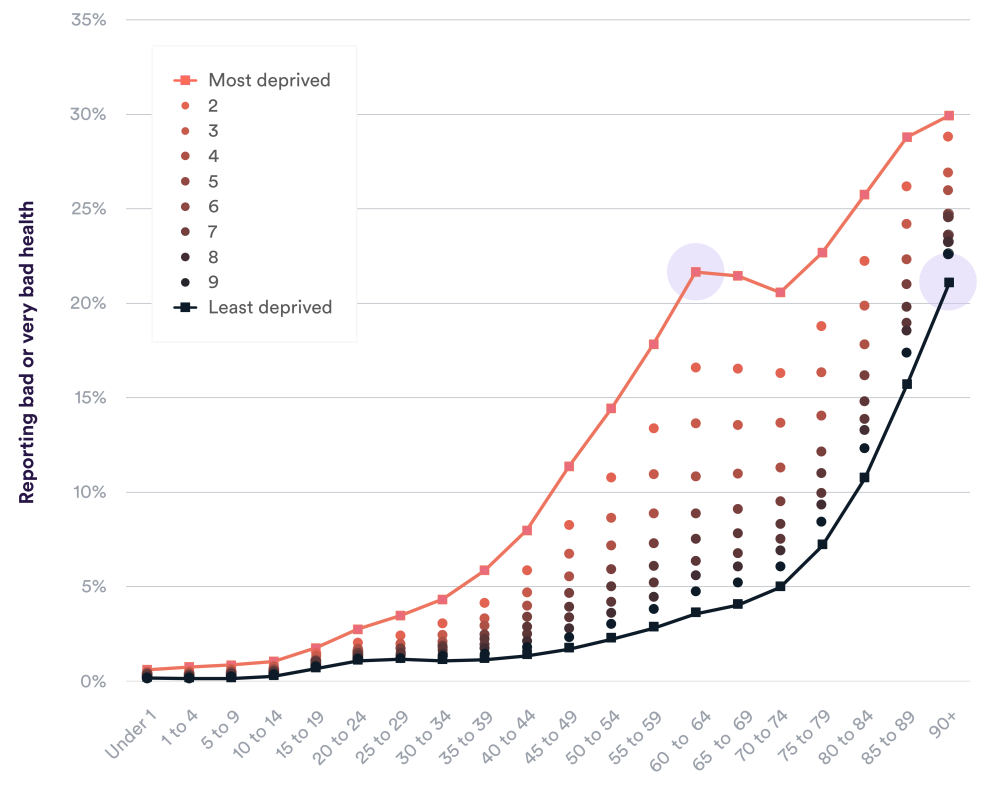

People aged between 60 and 64 living in the most deprived areas of England report similar levels of poor health to those aged 90 and over in the least deprived areas – data collected as part of the 2021 Census shows.

The 2021 Census asked everyone in the UK to report their general health based on a five-point scale from very bad to very good. The chart below shows the proportion of people who reported bad or very bad health, broken down by their age and the deprivation level of their neighbourhood in England. This self-reported health data illustrates how people living in the most deprived areas of the country systematically experience significantly poorer health than those in better off areas. These inequalities are apparent across all ages.

The widest gap between the most and least deprived areas is seen in those aged 45-49, where those living in the most deprived tenth of England’s neighbourhoods were over six times more likely to report poor health than their age peers in the least deprived tenth: 11.4% of those in the most deprived areas versus 1.8% of those in the least deprived. This health inequalities gap is evident from the first year of life (when the difference between the most and least deprived tenth of neighbourhoods is more than twofold) but begins to widen even further at age 25-29 and increases up until it peaks at age 45-49, before slowly narrowing.

Self-reported health data comes with some limitations. An individual’s experience of health is relative, and driven by contextual factors. Additionally, expectations of health may vary with age, which may be particularly evident between working and retirement age. Changes in expectation perhaps explain some of the temporary levelling off or reduction in poor health reported around retirement age. This seems more significant in the most deprived areas, perhaps reflecting the greater impact that poor health has on people working in manual jobs.

We know there are many factors contributing to the poorer health experienced by those living in the most deprived areas, which extend beyond access to care, including access to healthy food, housing, the experience of stress and poor air quality, among other social determinants. However, the higher prevalence of ill health in poor areas is a significant factor and challenge for health care services, which must be accounted for when planning and delivering care.