As the possibility of a no deal Brexit starts to move worryingly close to the time frame in which health care leaders have to make decisions, attention is turning to the small print of exactly what this dramatic scenario would mean.

Some high-profile reports, and much debate ahead of the recent Budget, have focused on what it would mean for the tax revenue that funds the service. Others have tried to calculate the price of stockpiling – sometimes forgetting that the ultimate amount of medicines the NHS needs would remain the same.

But what about permanent increases in the prices of the products the NHS purchases, driven by the sharp rise in red tape and trade barriers involved in a no deal scenario? These are not just one-offs like costs incurred in stockpiling: they will stay as an additional claim on the NHS budget every year until or unless trading relations change.

The level of uncertainty here is large and cannot be eliminated. As the government’s impact assessment notes, no country has ever left a major trading bloc before. But academic studies on trade, the facts of NHS finances, and the government’s impact assessment do give us enough to reach ballpark estimates for some key categories. [More detail on the assumptions I used can be seen in our supporting document.]

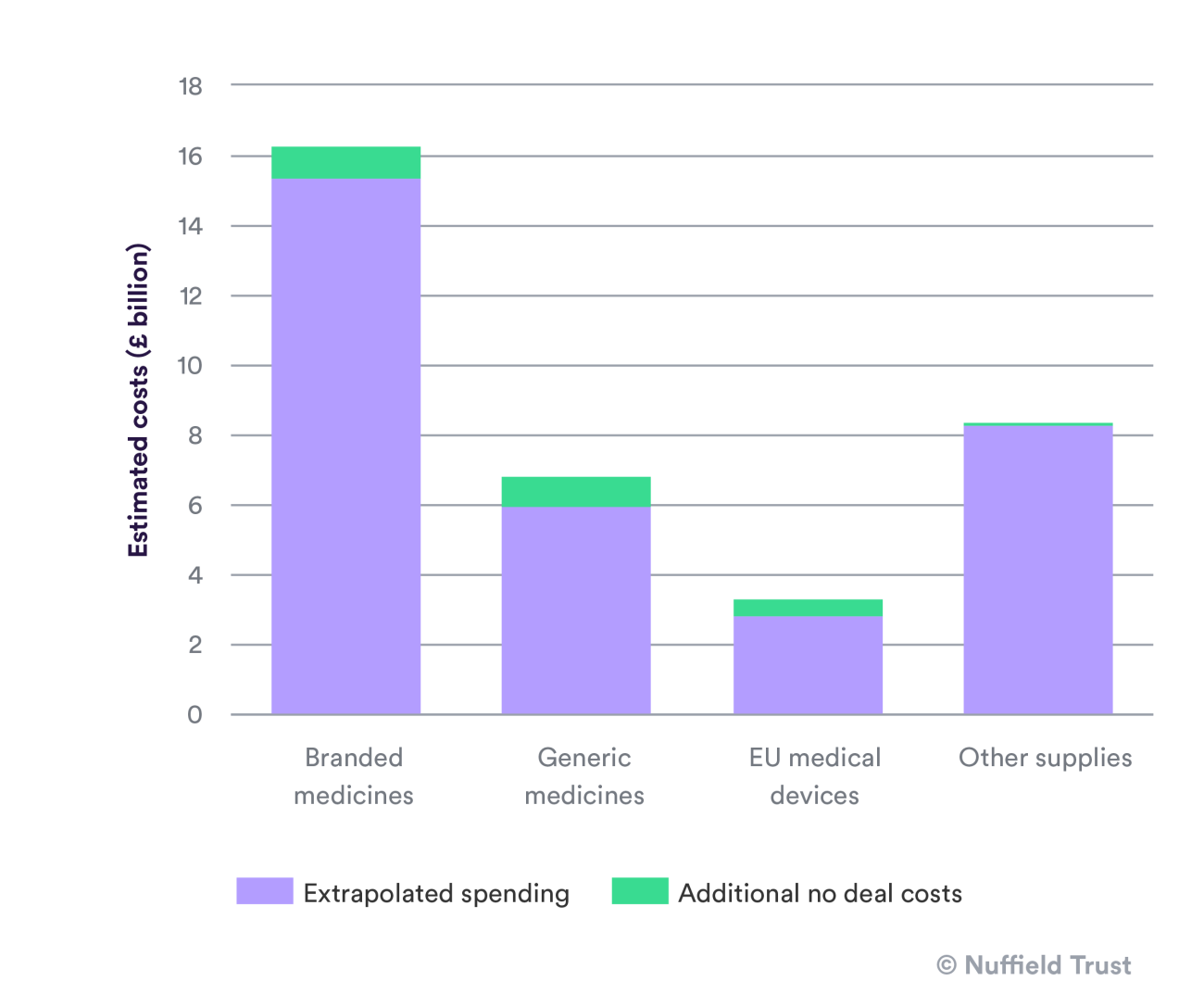

The overall figure adds up to £2.3 billion in extra costs for the NHS by the end of 2019/20.

Device prices

First, I looked at possible price increases for medical devices – everything from X-ray machines to syringes. HMRC stats show that in 2017 we imported around £3.4 billion worth from the EU. If we assume 80% were used by the NHS, in line with overall spending figures published by the OECD, and that this figure rises in line with health budgets, we would expect £2.9 billion to be spent on EU medical devices next year by health services across the UK.

How much would that increase under a no deal scenario?

Various estimates exist of the upward effect on prices of disruption to trade between the UK and EU under a no deal scenario. Unfortunately, none apply specifically to medical devices. I used the government’s estimate that “non-tariff barriers” would add the equivalent of 6.1% in costs in the “machines, equipment and energy” sector. This is an optimistic assumption, as many medical devices would fall in sectors where the estimated costs are higher.

An additional cost would be the impact of the devaluation of sterling. In line with estimates from banks, I assumed the pound would fall to be worth the same as the euro, raising costs by 14%.

The figure then needs to be adjusted down a bit to reflect that NHS buyers and suppliers would tend to react by shifting to cheaper devices, made in the UK or outside the EU.

Bringing these factors together suggest £470 million in extra costs on to the health service.

A tough pill to swallow

Next I looked at the biggest supply cost of all for the NHS: medicines. Last year the NHS spent around £11.3 billion on medicines prescribed by GPs across the UK. Within hospitals, so far only actual spending figures for English NHS trusts are available.

The prescribing figure will tend to be an overestimate, as discounts are secured on list prices. The hospital figure is probably a slight underestimate. Modest uncertainties in the baseline matter relatively little for the size of the additional costs.

Extrapolating these suggests total spending of £21.5 billion next year. Several different estimates shed some light on how that might change under a no deal scenario.

The University of Sussex’s UK Trade Policy Observatory has carried out modelling that, based on a particular set of assumptions, estimates that prices in the “chemicals and pharmaceuticals” sector would rise by 7.5%. Their model takes into account how sectors relate to one another, and the impact of losing the trade deals that apply to the UK through the EU.

An alternative approach would be to use the government’s non-tariff barrier estimates for the wider category of chemicals, rubber and plastic. This would give a roughly similar outcome.

Specifically for imports, I then added the effect of devaluation – using the estimate from Department of Health Permanent Secretary Chris Wormald that two-thirds of medicines used in the UK come from or via the rest of the EU.

We then need to consider how costs are passed on to the NHS. For branded medicines, there are mechanisms called the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) and the “statutory scheme” that limit the growth of spending through profit controls and by forcing companies to refund extra costs. But some medicines are also imported from other countries at below the UK price where this can be done profitably.

I make the simplifying assumption that all the extra costs of medicines counted towards the PPRS are passed back to the private sector, whereas the costs of other branded medicines are borne by the NHS. In reality, it may be that the Department of Health holds the line and forces nearly all costs on to the private sector – or that this just becomes unsustainable as companies face losses. I essentially assume a middle scenario where firms bear most but not all of the cost.

For unbranded medicines, cost increases can feed through more directly to the NHS, which has little choice but to raise the price it pays so that supply keeps coming. An example was seen last year when rising prices cost the English NHS an extra £315 million – perhaps partly due to the fall in the pound after the EU referendum.

Again, I adjust spend down to reflect the NHS trying to shift spending away from medicines as their prices rise. This leaves us with estimated net extra costs of about £830 million in unbranded medicines, and £920 million in branded medicines.

Adding up

What about other supplies and services the NHS buys in – from food and bedding, to management consultancy? If they rise in line with budgets, these will add up to around £8 billion across the UK next year. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research estimates that a no deal Brexit would result in inflation across all supplies rising to 3.2% next year, instead of 1.9%. Applying this rise in prices to the estimate of spending – after correcting what we have already counted separately – gives an additional increase of £88 million.

That takes the total to £2.3 billion.

The bigger picture

Other NHS budgets, too, might be affected by a no deal Brexit. Gaps in staffing if EU migration dried up could add millions to the bill, although the exact figure would depend on whether they were filled by non-EEA migrants, agency staff – or nobody.

Other factors would affect both NHS costs and the money available to fund it. As I have warned before, under a no deal scenario British pensioners abroad under the S1 scheme might be forced to return, potentially costing more than is saved through the cancellation of transfers under the scheme. Slower EEA migration would mean fewer patients, saving some money – although less than you might expect. But it would also mean fewer taxpayers.

While all the figures in this article are speculative to a degree, what is clear is that the magnitude of a cost shock to the NHS under a no deal Brexit would be considerable. The English health service’s share of £2.3 billion in higher bills would take up nearly all the money our calculations suggest will be free for improvements in patient care next year and the year after. Even a budget as large as the health service’s cannot absorb a 10-figure loss without patients feeling the effect.

*Read the supporting document showing Mark’s methodological assumptions behind the figures.

Suggested citation

Dayan M (2018) "How much would NHS costs rise if there’s no Brexit deal?”, Nuffield Trust comment. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/how-much-would-nhs-costs-rise-if-there-s-no-brexit-deal