Another dramatic change of leader part way through a parliamentary term has many commentators speculating about the new Prime Minister’s goals, intentions and policies. But for health and social care, she inherits a set of specific promises, made to the public in the 2019 Conservative Party Manifesto which is the platform every Tory MP was elected on.

Liz Truss has said explicitly that she will honour that manifesto. So what were the key promises it made about the major issues in health and care? And can they be honoured – or are some already all but broken?

We will build and fund 40 new hospitals over the next 10 years

Verdict: Not on course to be delivered.

This commitment refers to a specific programme begun in 2019. It has been questioned for its generous definition of a new hospital, which includes new wings added to old hospitals.

Even under this definition, the chances of success are minimal. Two of the 40 projects, Midland Metropolitan University Hospital and the new Royal Liverpool, were already under construction, and one had already been approved. The rest are all still awaiting approval, like the new Princess Alexandra hospital planned for Essex that has now been delayed by at least three years. Even when approved, planning, commissioning and building a hospital can take over seven years.

This matters because the pledge did genuinely address one of the NHS’s biggest weaknesses: the strikingly low amount spent investing in buildings and equipment compared to other countries. Setting aside new hospitals, the service currently faces a backlog of maintenance delayed due to lack of funding, including tens of hospitals with unstable roofs. Ms Truss will have to decide soon whether to protect the budget for buildings and machines, or to go back to raiding it as the Treasury has done repeatedly, storing up ever greater future problems.

Between 2018 and 2023, we will have raised funding for the NHS by 29%

Verdict: Depends on the Prime Minister’s decisions.

This commitment has its roots three Prime Ministers ago, when Theresa May announced a package of funding for the NHS’s 70th birthday later set down in law by Boris Johnson.

The 29% figure is on track to be exceeded in terms of the amount of cash in the NHS England budget for day-to-day spending, which is scheduled to rise 37% from 2018/19 to 2023/24.

Although the pledge appears to be in simple cash terms, adjusting for inflation is a more accurate way of counting whether the UK is actually putting more resources into health care. These “real-terms” figures are what previous Prime Ministers like David Cameron and Theresa May had usually used in their commitments. With inflation quite high in recent years, the real value of the increase will only be around 20%.

During her leadership campaign, the new Prime Minister said she would spend money allocated to the NHS following the health and care levy on social care instead. It is very difficult to tell what exactly this means, as there is no clearly defined pot of money specifically from the levy in the NHS budget. However, if more than £9.5 billion was removed in 2023/24, this would break the commitment even in cash terms.

50,000 more nurses by the end of this parliament

Verdict: Could still be delivered.

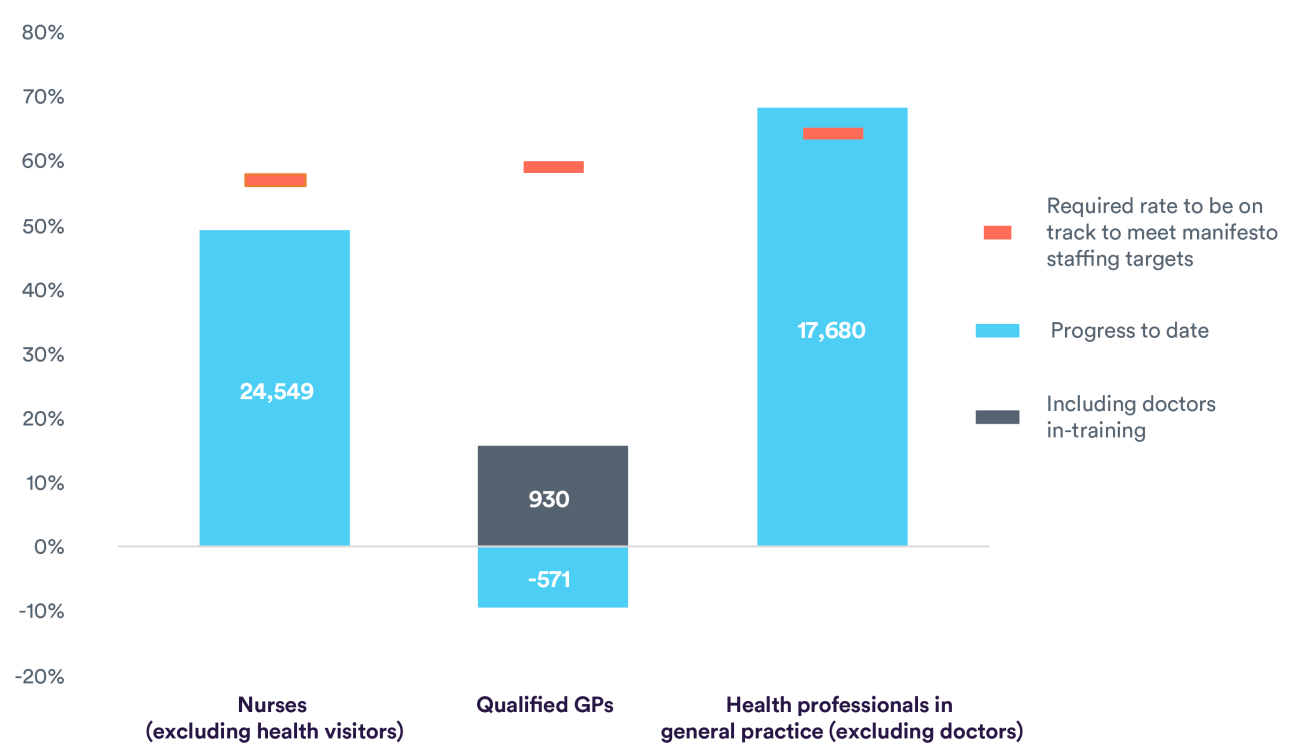

Although there has been a significant increase in numbers over the last couple of years, we would have expected to see over 28,400 additional full-time nurses in post by now. The figure up to May 2022 (from December 2019) shows an increase of 24,500.

Reaching the 50,000 target by the end of 2024 may be achievable, but it will not be without its challenges. The UK has increasingly relied on international recruitment in recent years and, in the year to March 2022, 45% of nurses joining the English NHS had a non-UK nationality. But it is uncertain how much these increases can be maintained, given the global nature of the nursing labour market. This will pose a specific challenge to the NHS, given the longstanding failures to accurately project future supply of and demand for staff. In the short term, overseas recruitment will have to remain as a vital way of expanding nursing numbers.

Alongside this, it is imperative that better understanding of and action on the reasons for leaving is prioritised, to prevent nurses exiting the profession earlier than they otherwise would – particularly given the prospect of looming industrial action on the horizon.

6,000 more doctors in general practice and 26,000 more primary care health professionals by the end of this parliament

Verdict: not on course to be delivered for doctors; on course to be delivered for primary care health professionals.

The former Health Secretary Sajid Javid admitted himself that the government is not on track to meet this target. Since December 2019, there has been a fall of 570 fully qualified GPs from the workforce. Even when including trainees, who may not end up as fully qualified GPs, the increase is still only 930. We should be seeing well over triple that amount at this point.

There is also stark regional variation between areas of England. Even after accounting for patient need, Hull has 2,485 patients per one GP, compared to 1,327 patients per one GP in Liverpool. These differences can increase inequalities in accessing GP services, which in turn may impact the quality and experience of care for patients.

The government appears on track to deliver 26,000 more primary care professionals (including physiotherapists, pharmacists, and social prescribing link workers). However, with an increasing number of GPs contracted to work part-time hours, and many approaching retirement age, we have grave concerns that access to and public satisfaction with general practice – which is already falling – may get even worse.

50 million extra general practice appointments a year by 2024/25

Verdict: Not on course to be delivered, but may be achievable.

The number of GP appointments has now recovered to pre-pandemic levels, after falling by 30% during the first Covid-19 wave. Appointment numbers do fluctuate from month to month, but are now following a very similar trajectory to before the pandemic – increasing but at a slow rate.

But we are still far from reaching the target of 50 million more general practice appointments a year by 2024/25. This would require an overall increase of 16%, but in 2021/22 (a couple of years since the target was introduced) appointments had only increased by 4%. This indicates that progress on increasing appointments is currently lagging behind and that we are not on track to meet the target. Unless we see the number of GPs and practice staff grow, it will be difficult to secure the extra capacity needed to meet this commitment.

The latest GP Patient Survey results reinforce the scale of the challenge, as they show that patients are actually having a poorer experience of making an appointment. Only 56% reported a good experience of making an appointment in 2022 – the lowest level for five years and a decrease from 71% in 2021.

Reform social care to give every person the dignity and security that they deserve

Verdict: Not on course to be delivered.

This broad pledge recognised the poor state of social care in 2019, when tens of thousands of people needing support received nothing, and staff and companies providing care alike were being pushed out by years of cuts. The manifesto specifically promised an extra £1 billion in funding, and “a guarantee that no one needing care has to sell their home to pay for it”.

Last year’s white paper did lay out some of the right aspirations for an improved system, but a lack of funding and staff threaten progress. A more generous means test and a cap on care costs are scheduled to be introduced, but the cap will be set at £86,000 and will exclude any contributions made by councils. This likely will not prevent some people needing to sell their homes, and will provide limited financial protection generally to those with modest wealth.

While £1 billion extra was delivered, spending per adult remains lower than it was 12 years ago. Reform plans focus on shifting who pays but do little to increase the amount or quality of care. Poor pay and conditions, as well as a migration squeeze after Brexit, saw alarming declines in staffing last year. There is a real risk that far from every person getting the help they deserve, even more people who need care will go without in 2024.

Tough times ahead but progress is possible

The new Prime Minister will start her job with a mountain to climb if she wants to tell voters at the next election that key promises around health and care were delivered. Some already seem impossible, casualties to Covid-19 and the ingrained refusal to prioritise funding for social care or long-term investment. But this is not a total counsel of despair. If there is a clear focus on the staff and buildings that the NHS needs, and on supporting general practice to deal with the difficult hand it has been dealt, there are still pledges that could shift from seeming unlikely to being delivered.