Last Friday, NHS hospitals in England were each told how much of the next year’s £2.1bn 'Sustainability and Transformation' fund they can expect to receive.

In an ideal world, all the cash would be available for investment in new services and models of care. In reality, however, almost all of next year’s fund - £1.8bn of it – will be spent on bailing out NHS providers in deficit, leaving just £339m to fund 'transformation'.

The cash is the first tranche of £14bn earmarked by NHS England for spending on the radical transformation of NHS services needed over the next five years.

In an ideal world, all the cash would be available for investment in new services and models of care. In reality, however, almost all of next year’s fund - £1.8bn of it – will be spent on bailing out NHS providers in deficit, leaving just £339m to fund 'transformation'.

NHS England has said that will change: as NHS providers come back into balance, so more of the £3bn or so a year fund will be spent on 'transformation'.

There is a need then for some transparency and honesty about the current scale of NHS provider deficits and the time and cash it will take to clear them.

The most optimistic estimate of the current financial year’s net underlying NHS provider deficit is now around £2.1bn – a figure which would still entail a huge improvement from the mid-year trajectory of over £3bn.

At bottom, that deficit is born of a trading gap between the income hospitals and other NHS providers earn and their costs. Understanding how that gap has come about and its recurrent (rather than one-off) nature, is key to understanding how it can be filled, and how long that will take.

Provider deficits: how it got this far

NHS hospital income is largely determined by the NHS tariff – a national price list for thousands of different standardised treatments or episodes of care.

Like other parts of the economy, NHS providers are affected by rising costs – most significantly staff wages and drugs. But although tariff prices are nominally increased each year to recognise that pressure, in recent years those price increases have been outweighed by a hefty 'efficiency assumption' which requires NHS trusts to effectively absorb the inflationary pressures they face by making year-on-year cuts to their running expenses in order for the tariff price to continue to cover their costs.

Each year from 2011-12 to 2014-15 the efficiency requirement asked trusts to make cost savings of four percent: all other things being equal, that is the equivalent to asking for an input costing £100 in 2010-11 to cost just £85 in 2014-15.

The rub, however, is that NHS trusts have not kept up with these high efficiency requirements. Figures from the NHS foundation trust regulator Monitor show that in 2013-14 foundation trusts (now the bulk of NHS providers) managed around three percent and in 2014-15 just 2.5 per cent.

Every percentage point gap between the tariff efficiency requirement and what NHS provider trusts actually achieve is the equivalent to a deficit of around £600m-700m. And just as the efficiency requirements are recurrent – accumulating year on year – so too are any gaps between income and costs which result from them being missed: each prior year’s gap is the starting position for the subsequent year. The hole just gets deeper.

It is therefore not surprising that the NHS deficits currently making news headlines are not particularly new. In 2013-14, NHS providers ran up an underlying deficit of £600m (somewhat obscured from view by Department of Health bailout loans). That was almost exactly equal to the one percentage point gap between the efficiency requirement implicit in the tariff for the year and the lower level of cost reductions trusts actually achieved.

Trusts then started their 2014-15 trading £600m behind. As they went on to miss the efficiency requirement for that year by around 1.3 percentage points (reducing costs by 2.7 percent rather than the four percent required) they widened their trading gap further still, boosting their underling deficit by a further £900m to £1.5bn.

Again, that meant trusts started this current financial year £1.5bn behind. Halfway through this financial year, Monitor reported NHS foundation trusts were making average cost improvements in the region of 2.5 percent against a tariff efficiency requirement of 3.5 percent. If that continues, it will be equal to a further £600m to £700m on the deficit, taking the deficit for the full year to around £2.1bn or £2.2bn.

Will a sustainability fund balance the books?

This is the context against which the new NHS economic regulator NHS Improvement last week began the process of divvying up £1.8bn of sustainability funding to predominantly NHS hospital providers for 2016-17.

The fund will be used to artificially boost trust income for 2016-17 – partially bridging that £2.1bn or so gap created by recurrent years of missed tariff efficiency requirements.

If we optimistically assume trusts will start the year £2.1bn behind, next financial year’s sustainability fund will close the gap to £300m-£400m. It is surely then no coincidence that the efficiency requirement for 2016-17 has been reduced to just two percent: half a percent below the level providers are currently achieving, implying a £300m-£400m gain to the collective bottom line.

It will be the Department of Health and NHS England’s hope that those two moving parts will come together to create a balanced NHS provider position at the end of 2016-17: A £2.1bn negative starting point, nominally fixed through £1.8bn of extra sustainability funding plus £300m or so of surplus efficiency gains above those required to cover cost inflation unfunded by the tariff.

But even if those sums do add up, the problem will be far from fixed.

The £1.8bn sustainability fund does nothing to fix the underlying trading gap between the prices paid by the tariff and the costs hospitals actually face. Take the fund away, and hospital trusts will start the next financial year (2017-18) just £300m better off than the start of 2016-17: in other words, with an underlying deficit of £1.8bn.

How then can NHS providers recover?

If politicians cannot tolerate an NHS in deficit for another seven years, the alternative option is for a far larger proportion of NHS England’s £14bn 'Sustainability and Transformation Fund' to be spent on sustainability over the next five years than has so far been made explicit.

As the NHS tariff efficiency requirement is now expected to stay at two percent a year for the next five years, it might seem reasonable to assume that hospitals will continue to marginally better it by making recurrent annual savings of 2.5 percent – making a fresh £300m or so available each year to gradually close down the deficit in their trading position.

Doing so would imply NHS hospitals finally breaking even at the end of 2022-23, at best – possibly three years too late for politicians and certainly too late for many NHS trusts whose accumulated deficit position already means they have less cash coming in than they need to pay out in staff salaries and other costs.

This is where the need for honesty at the top comes in – and the implications for the rest of the NHS to be understood.

If politicians cannot tolerate an NHS in deficit for another seven years, the alternative option is for a far larger proportion of NHS England’s £14bn 'Sustainability and Transformation Fund' to be spent on sustainability over the next five years than has so far been made explicit.

Indeed, it may be that this has already been acknowledged internally: last month, NHS England announced that Greater Manchester’s fair share of the transformation-only element of the fund would be £450m over the five years. Assuming Greater Manchester’s fair share would be measured with reference to its 5.4 percent share of population (weighted for health need), we can extrapolate that NHS England expects the total 'transformation' element of the £14bn cash to be in the region of £8bn, leaving £6bn, over five years, to spend on provider sustainability.

While a £6bn sustainability fund would allow for a more comfortable easing of hospital deficit and cash flow positions, it has obvious implications for the size and profile of the remaining transformation fund.

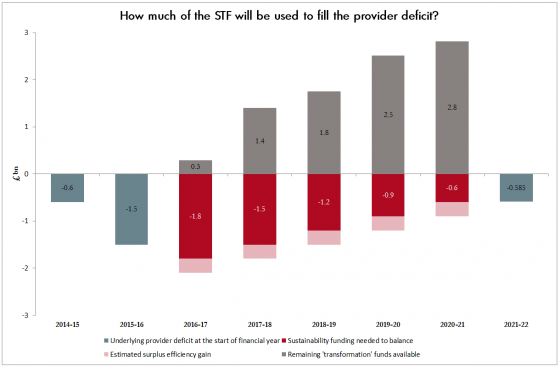

Assuming providers are able to make £300m inroads into their underlying deficits each year would mean that £1.5bn of sustainability funds would be needed in 2017-18, leaving the balance available for transformation that year at £1.4bn. That would increase to around £1.8bn for transformation in 2018-19 as funds needed for sustainability would reduce by a further £300m to £1.2bn. Finally, by 2020-21 this set of assumptions would see providers needing around £600m in sustainability, leaving £2.8bn to be spent on transformation.

Is there an alternative?

Providers could, in theory, close their underlying trading gaps faster by finding greater efficiency savings, above the current level of 2.5 percent cost savings a year – roughly £1.5bn a year.

But we have to ask how realistic a prospect that is. Lord Carter’s much heralded work on acute hospital productivity finds that “at least” £5bn of savings can be found by the end of this decade. It is not at all clear, however, whether or not that £5bn is in addition to the savings trusts will be expecting to find in the normal course of their business, i.e. meeting the annual tariff efficiency requirement.

There is also the very real prospect that the underlying deficit for 2015-16 will significantly exceed £2.1bn. Acute hospitals in particular report additional cost pressures beyond missed efficiency requirements, in particular higher rates of staffing needed to meet safer staffing requirements since the publication of the Francis report in early 2013.

As Richard Murray at the King’s Fund points out, the fact the sustainability element of next year’s fund has been ring-fenced by the Treasury for specific controls is indicative of the chancellor’s growing concern over the ability of the Department of Health and its quangos to get a grip on the NHS’s finances.

Cascaded down to individual NHS trusts, these controls are being played out as a strict set of terms providers must sign up to in order to access their share of the cash. These include agreeing to capital spending controls: effectively stripping NHS foundation trusts of their freedom to determine their own investment plans – a long-running bugbear at the Treasury. The move is necessary to balance the Department of Health’s books, since much of next year’s sustainability fund will be funded by slashing the department’s capital budget, against which NHS and foundation trust capital spending scores.

But advocates of the foundation trust model will argue that this attack on the essence of foundation trusts' organisational independence will strike at precisely the sort of innovative investment required to both develop new models of care for the future and make radical new inroads into productivity.