Chronology: the second decade

1958

Background

Boeing 707 in service

NHS events

Effective treatment of blood pressure

Asian Influenza pandemic

Thiazide diuretics

44-hour week introduced for nurses

Platt Report on welfare of children in hospital

1959

Background

Election: Conservative majority 100

“You’ve never had it so good” (Macmillan)

Morris Mini

M1 motorway opened

NHS events

Nursing Studies Unit (Edinburgh)

Wessex becomes a regional hospital board (RHB)

Cranbrook Report on maternity services

Mental Health Act

Hinchcliffe on cost of prescribing

1960

Background

Last call-up for National Service

Noise Abatement Act

NHS events

Royal Commission on remuneration of NHS doctors and dentists

Tranquillisers, Librium

Royal College of Nursing (RCN) admits men for first time

1961

Background

Pay pause

First man in space

NHS events

Ampicillin

Oral contraception in family planning clinics

Standing Nursing Advisory Committee (SNAC) on pattern of the inpatient’s day

Enoch Powell’s Water Tower speech

Standing Medical Advisory Committee (SMAC) report on accident services.

Human Tissue Act

Thalidomide disaster

Platt – hospital medical staffing

1962

Background

Cuban missile crisis

“Turn on, tune in, drop out”

Second Vatican Council

NHS events

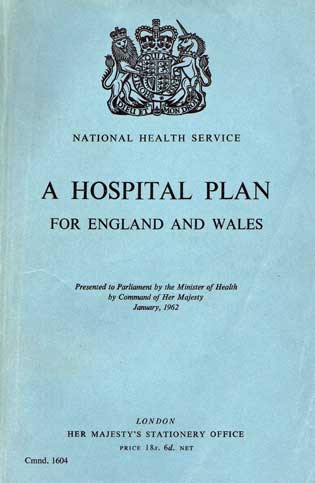

Hospital Plan (Enoch Powell)

Royal College of Physicians (RCP) Smoking and health

Committee on Safety of Drugs

Smallpox scare

Porritt Report

Oral polio vaccine

1963

Background

Kennedy assassinated

Beatles

Profumo/Keeler

NHS events

First liver transplant

SMAC on communication between doctors, nurses and patients

1964

Background

Labour government

Harold Wilson Prime Minister

NHS events

RCN report on reform of nursing education

1965

Background

NHS events

Charter for family doctors

Downward trend in birth rate

TV advertising ban on tobacco

SMAC on standardisation of hospital medical records

Royal Commission on Medical Education and Seebohm Commission appointed

1966

Background

Election: Labour returned

Sterling crisis; pay freeze

England wins World Cup

Aberfan disaster kills 144

NHS events

Salmon on senior nursing staff structure

70 per cent of babies delivered in hospital

Measles vaccine

Establishment of cervical cytology service

New GP contract

Enoch Powell’s book New look at medicine and politics

1967

Background

Torrey Canyon oil spill disaster

NHS events

Coronary bypass grafts

Abortion Act

Heart transplantation

Health Education Council established

Cogwheel Report on organisation of medical work in hospitals

Sans everything

General Practice Finance Corporation

NHS structure to be examined

World Health Organization (WHO) embarks on eradication of smallpox

Ten years on

The beginning of the second decade of the NHS saw the end of the years of post-war austerity. The NHS was also about to make substantial progress. Public opinion surveys showed that the vast majority wanted the NHS to continue, with or without modification. The Lancet, which had initially feared that the NHS would prove inflexible, was pleased this was not so. Having urged government to take tuberculosis more seriously and build to provide more beds, this was not now necessary. However, in the face of the shocking overcrowding of mental hospitals, more beds seemed to be needed. Now enterprising hospital units were looking at a system in which most patients would go on living at home while under treatment. Within another ten years one might be wondering what to do with the many mental hospitals that were plainly unsuitable for the proper practice of psychiatry. The Lancet noted that fresh approaches were affecting the nature of the hospital itself; many more patients would in future visit the hospital instead of living in it. ‘Cafeteria medicine’ had a real future and it was futile to waste the service of skilled nurses on people who did not in the least require them. GPs should pay close attention to the way in which hospitals were reaching out ever further towards the home. A family doctor should give everyday medical care, but a high level of general practice would not be preserved unless those with faith in it were prepared to translate their faith into works.1

Although medical staffing had been improved, hospital laboratories and X-ray departments were lagging behind and were ill-equipped to meet new and complex requirements. There had been neither the money nor the time to deal with the run-down condition of hospitals. The British Medical Journal (BMJ) saw much in the NHS that was good, and much that was bad. It was the job of the medical profession, in co-operation with the government, to improve matters. The NHS should not be regarded as something fixed and immutable and the private possession of Mr Bevan.

The end of the first decade of social revolution finds the profession in no mood for jubilation. The politicians must inwardly regret their enormous errors of calculation. Whatever benefits it has received, the public is beginning uneasily to wonder whether the price has not been too high in this free-for-all scramble for medical attention.2

The BMJ suggested looking at the systems in other countries and thought that patients might take a more direct financial share in their own welfare, though the Chairman of the Council of the British Medical Association (BMA) conceded that, from the point of view of the ‘consumer’, it had been an enormous benefit and success, as anyone taken ill on holiday rapidly discovered.3

During the anniversary parliamentary debate, Bevan, now Shadow Foreign Secretary, was on his feet. Two concepts underlay the health service. First was the provision of a free comprehensive service, and all the drugs and facilities that would not have been available to the masses under the old system. Second was the redistribution of income by central taxation so that those who had the most paid the most. The Conservatives had opposed this redistribution. He spoke of private practice and pay-beds, concessions that were sometimes seriously abused. For financial reasons, he said, some consultants enabled private patients to jump the waiting list. The Minister, Walker-Smith (the seventh in the first ten years of the NHS), pointed to the successes (health promotion, poliomyelitis vaccination and fluoridation of water); the need to plan health services for the ageing population; the developments in mental health; and the potential for economy in the hospital service by using work study, and organisation and methods studies.4

Lord Moran had fought for the consultants’ interests. He wrote that the overwhelming majority of them would prefer the current conditions. Bevan’s plan had been more liberal than that of Willink, the previous Conservative Minister. Under the Conservatives, the doctor would have been a local authority employee. Consultant services had expanded; in the Newcastle region there had been 164 consultants in 1949, and in 1957 there were 409. Hospitals had been upgraded and a third of consultants got merit awards. Moran said that clinical research in the NHS was not starved of money – the problem was shortage of good researchers. Under the NHS, academic medicine had grown in prestige and influence. However, someone, sometime, somewhere must call a halt to the soaring expenditure on the NHS. Rebuilding was relatively unimportant, particularly of mental hospitals. The priority was people of first-rate ability to add to knowledge of the mind in health and disease. The Ministry should bid in the open market for the best brains; there must be rewards for a few people at the top comparable with those offered in other callings.5

Changes in the hospital service, 1949–1958 (England and Wales)

|

|

1949 |

1958 |

|

Occupied beds (1,000s) |

398 |

418 |

|

Deaths and discharges (1,000s) |

2,937 |

3,983 |

|

TB occupied beds (1,000s) |

26 |

17 |

|

Waiting lists (1,000s) |

498 |

443 |

|

Outpatients (millions) |

6.15 |

6.97 |

|

Mental hospitals |

||

|

Certified patients |

119,943 |

76,665 |

|

Voluntary patients |

20,160 |

61,120 |

Source: Annual Report of the Ministry of Health for 1958

Sir Harry Platt, far more progressive than most of his generation, also supported the service. The unification of hospitals of all types into a single system, the establishment of the region as a planning unit and the more even distribution of specialists were substantial achievements.6 Problems included the fragmentation of the service into three parts. There was excessive expenditure on drugs when the money could be better spent by upgrading hospitals, building new ones, and enabling leading hospitals to keep abreast of medical science, particularly the university hospitals.7

The BMA representative meeting in Birmingham established a committee with the Colleges and the medical officers of health (MOsH), to review the NHS in the light of ten years’ experience, and to study alternative schemes for a health service.8 It was called the Porritt Committee after its chairman, a natural choice for such a role. Not since the Medical Planning Commission’s interim report of 1942, said the BMJ, had a group as representative of all branches of medicine been asked for an opinion on how the nation’s health services should be organised. The NHS had come to stay but it must not be allowed to become stale.9

On becoming Minister of Health in 1960, Enoch Powell agreed that there were risks of rigidity in a great, but centralised, service. He saw three trends running side by side: the growth of community care and after-care of the sick, relieving the hospital; the development of preventive and remedial measures; and the more intensive and efficient use of hospital accommodation. He wanted fewer beds in newer hospitals. The three separate financial systems for hospitals, local health authorities and general practice were a great weakness. The BMJ wished his stay in the Ministry long enough for the provision of effective remedies.10 When in due course he moved from the Ministry, he was one of the few ministers whose departure was a source of ‘deep regret’ to the profession.11

Changes in society

According to Sir Francis Fraser, a physician, Director of the British Postgraduate Medical Federation, and one of the group that produced The development of specialist services, changes in society were affecting medical practice.12 Social barriers were disappearing. There was an increasing number of people seeking help for illnesses in which social or mental conditions were important or dominant. Was this the result of the lack of support from religious beliefs, the mechanisation of industry, the loosening of family and community loyalties, increasing urbanisation and new towns, the boredom of life under the welfare state, and a dependence on newspapers, television and wireless for ethical and moral values and codes of behaviour? Many people seemed unable to adapt to the speed of change in social conditions. The young had been acquiring a new degree of economic and social freedom that affected their personal relations with everyone, including their doctors.

Before the second world war, Stephen Taylor had described suburban neurosis, anxiety and depression among people living on estates, which he attributed to boredom, loneliness and a false set of values. The war and the air-raids had done much to build a community spirit and reduce neurotic illness. Now new building, large blocks of flats and relocation in new towns were re-creating suburban neurosis. The incidence of ‘nerves’ on new estates was double that in more settled areas.13 A more dramatic problem was the emergence of a drug subculture. Flower-power, and “the iconoclasm of hippiedom and the ill-considered advocacy of people who should know better” were creating an atmosphere, not only of drug taking, but also of opposition to firm action to control its spread. Designer drugs such as the hallucinogen STP, a powerful and dangerous amphetamine derivative, spread from across the Atlantic.14

Medicine and the media

Charles Hill, ‘the radio doctor’, had been broadcasting on health issues since the early 1940s and the media were telling people more about medicine. Many doctors thought that, although people should know about health promotion, detailed knowledge of disease was not desirable. The BMA’s own publication Family Doctor trod carefully. It did not carry advertisements for the Family Planning Association. There were “obviously grave doubts about the wisdom of publishing in a popular health magazine issued by the BMA to the public, and read among others by teenagers and by the immature, an advertisement which might be held to give the green light to contraceptive practices”.15 There was a row in the BMA when, in 1959, Family Doctor ran articles on ‘Marrying with a baby on the way’ and ‘Is chastity outmoded?’ The entire stock was ceremonially pulped amid accusations that the BMA was engaging in censorship.16 The BBC televised a series of five programmes on ‘The hurt mind’, described by Kenneth Robinson (Minister of Health (1964– 1968), son of a GP, protégé of Bevan and a member of a regional hospital board (RHB) with a keen interest in mental illness), as perhaps the most significant breakthrough in the mass communication field. Doctors, however, alleged large numbers of patients crowded down to their surgeries to ask for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). On 11 February 1958, the BBC broadcast the first of a new series, ’Your life in their hands’. Charles Fletcher, a physician at the Hammersmith Hospital who presented it, was concerned about the problems of doctor-patient communication. He thought doctors failed to explain adequately the nature of illness and its treatment. The programmes included cardiac surgery, a brain operation, and an operation on the liver. This open approach was unpopular with many of his colleagues. The BMJ considered that it was demeaning for doctors and nurses to appear as “mummers on the stage to entertain the great British public”. People’s anxiety about their health would be heightened, increasing hypochondria and neurosis. Hopefully the BBC would not televise a death on the table in its presentation of topics that, though familiar to medical men, were full of mystery, fear and foreboding to the ordinary person.17 A doctor wrote to say that, as a result of a programme, a patient had correctly guessed that he was suffering from cancer. Questions were asked in the House of Commons. A ward sister was anxious that patients in her ward receiving deep X-ray therapy would realise what it was for. People had fainted while watching televised operations, sustaining head injuries. Writers to the Nursing Times were divided in their views: one said that the programmes had sparked interest in nursing among schoolgirls; a patient wrote how encouraging it was to see the rapid developments in medicine; and a third compared the programmes to bygone Sunday visiting at Bedlam and said the BBC had lost all refinement of feeling and sense of proportion.18 TV had discovered a new and popular genre.

The lay press relished the attempt by some doctors to keep their own secret garden. William Sargant, medical adviser to ‘The hurt mind’, said that there were 5,000 suicides each year, many among depressed people for whom help was available. If even a few of them went to the doctor to ask for treatment, was this wrong?19 The BBC’s audience research team found that its audiences liked the programmes. The study fell short of the quality the BMJ expected. Inference from the population studied, it said, would demand a degree of recklessness that would land most statisticians in ‘Emergency – Ward 10’. Casting its own scientific standards to the wind, the journal said “There can be no doubt of the danger to the unstable with a morbid curiosity about blood and bowels, to frail worriers, and to those with serious disease who may receive interpretations different from those given by their own doctors”.20

The Ministry received many complaints about the gulf in communication between doctors and their patients. Enoch Powell, then Minister of Health, asked the Standing Medical and Nursing Advisory Committees (SMAC and SNAC) to advise on what could be done. Lord Cohen reported in 1963 that well-founded criticism was rare, but that poor buildings, crowded facilities and lack of secretarial services did not help.21 Nevertheless, the doctor, nurse and patient were at the centre of the service and must take responsibility. Outpatients should be treated as individuals and listened to, staff should identify themselves and some might wear badges. Clear information about hospital life should be available. The BMJ thought it a disappointing report, not based on enquiries into the extent of the problem. The difficulties lay in the hurried conditions of hospital practice, and the value of ministerial missives was doubtful. When there were enough hospitals, fully staffed and planned on modern lines, doctors would have the time and space to correct the lapses of behaviour that were inevitable when faulty communications corrupted good manners.

Medical progress

Health promotion and screening

By the 1960s many countries were beginning to realise that they faced new health problems requiring different solutions. Infectious disease was being conquered but demographic trends and the growing proportion of old people were leading to a greater prevalence of chronic disease, and mortality from cancer of the lung and coronary thrombosis was increasing. There was concern about persisting inequalities in health and health care, and the emergence of new environmental hazards that urgently required regulation. Smoking was prevalent in all classes but public knowledge about the associated health risks was vague and ill-formed. In 1967 the Health Education Council was established, a successor to the Central Council for Health Education, to co-ordinate planning and organisation of health promotion, paving the way for a more scientific approach, a broader conceptualisation and the first tentative attempts at evaluation.22

Screening is the presumptive identification of unrecognised disease or defect by the use of tests or other procedures that can be applied rapidly. Screening tests sort out apparently well people who probably have a disease from those who probably do not. They are not diagnostic; suspicious findings are referred for diagnosis and treatment.23 Screening may be undertaken for research, to protect the public health, as in the investigation of an epidemic, or to attempt to improve the health of individuals. It stands apart from traditional medicine in seeking to detect disease before there are symptoms and medical help is sought. Screening therefore had an ethical dimension, for it could change people’s perception of themselves from healthy to sick. Intervening in the lives of those who are at no great risk is unreasonable; one cannot assume that diagnosing a disease earlier will necessarily help without randomised controlled trials to check the effectiveness of earlier diagnosis.24 Multiple screening programmes evolved in the USA during the 1950s. British medical opinion was divided on whether clinical examination and a battery of laboratory tests and X-rays were worth while. The BMJ came down against them, saying that the lay view of matters medical was usually ill-informed and singularly opinionated.25 Check-ups carried dangers of missing disease already present, false reassurance or undue alarm about an abnormality best ignored.

The regular examinations in child welfare clinics were one form of screening. Among the ideas being explored were selective examinations and ‘at-risk’ registers. In 1958 Baird introduced a paper test checking nappy urine to test newborns for an inborn metabolic disease, phenylketonuria (PKU), and in1961 a blood test collected as a dried spot on filter paper was introduced by Dr Robert Guthrie in New York. This led the Medical Research Council (MRC) to call an immediate conference. By 1959 the City of Birmingham was testing all new-borns, and soon local health authorities were advised to screen babies between four and six weeks old, a task that fell to health visitors.26 In many areas, screening tests for single diseases were now widely applied, for example, accurate hearing tests in school children. By the early 1960s, pre-symptomatic identification of a wider range of disease was possible. In Rotherham, the local authority health department organised screening for five problems: anaemia, diabetes, chest disease, deafness and cancer of the cervix. For three weeks once a year, the department did nothing else. Individuals at the lowest risk flooded in; those at high risk did not come. There were a substantial number of positive findings that were referred to GPs, but the communication between the Medical Officer of Health (MOH) and the GPs was sometimes poor.27

There was a naive belief that, if something was diagnosed early, one could cure people, and if several tests were combined there was a synergy. Some thought that screening should be carried out by group practices, in health centres or with the agreement of the local GPs in local health authority clinics. Others sensed a premature rush into untried and possibly ineffective procedures. People in the MRC, the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust and the Ministry felt the need for caution. Max Wilson, a senior medical officer at the Ministry of Health, was sent to the USA for several months to study screening there and was the joint author of a key report from the World Health Organization (WHO).28 A subcommittee of SMAC, chaired by Thomas McKeown, Professor of Social Medicine at Birmingham, was established to take a calmer look at the possibilities. Archibald Cochrane, who had been involved in several projects related to screening, was a member. There were four important requirements before screening should be undertaken:

- There should be an effective treatment

- There should be a recognisable latent or early symptomatic stage

- There should be a suitable test or examination acceptable to those to whom it was offered

- The criteria for diagnosing the disease should be agreed.

There was little doubt that the early detection of some diseases such as anaemia, glaucoma and cervical cancer was important. It was necessary to have a way of establishing contact with high-risk groups; antenatal services and infant welfare services enabled contact to be made with some age groups, but for others, for example, the elderly and those at risk from cancer in middle life, accessibility was not so easy.

Changes in hospital care

A profound change was taking place in medicine, altering the style and organisation of clinical services. Formerly treatment was often determined on a once-for-all basis, and the consultant could visit daily or even only twice a week.29 Now treatment was a continuous process that, in serious cases, might alter from hour to hour, in which laboratory investigations played an important part. Diagnosis had depended on history taking, a precise and carefully taught system of questioning to determine exactly what patients experienced, and the timing and nature of symptoms. Although laboratory tests had been available to confirm and occasionally make a diagnosis, the patient’s story was pre-eminent, often more revealing than physical examination. Lord Moran had looked after Winston Churchill throughout the war, during heart attacks and other serious illnesses, with no more complex equipment than a stethoscope. Outpatient care became more common and a smaller proportion of patients needed admission. Gone were the days when the outpatient department was merely the place in which eager doctors found candidates for their beds, or dismissed those who had recently occupied them. Whether the outpatient was given the same thoughtfulness, care, understanding and explanation that inpatients could expect from the nurses was doubtful. The responsibility for the patients’ comfort, wrote an outpatient sister who later became an author of renown, lay primarily with the nurse but also with doctors, who should remember that, to the patients, their time was not expendable.30

Much depended on an increasing ability to measure bodily structure and functions. The introduction of computers aided the process.31 Better measurement improved the understanding of the physiological effects of disease and the effect of intervention. Radio-isotope techniques, a by-product of research at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell, led to a wide range of new tests for blood loss and blood formation, and for thyroid disease. A paper dip-stick test for protein in the urine made a common procedure quicker and more pleasant.32 Biochemistry laboratories reported workloads increasing by 15 per cent a year. Automation in the laboratory became possible. In histology it aided the preparation of specimens, and in haematology the Coulter counter used changes in conduction as cells passed in single file in a rapidly flowing stream through a narrow orifice. In biochemistry continuous flow analytical methods were incorporated into the AutoAnalyzer.33 Twenty-five different tests were adapted to run on the AutoAnalyzer and multi-channel equipment was developed. Laboratories began to offer package deals in which several related tests were carried out whenever one of them was requested.34 Bewildered doctors, having asked for a blood urea, found the report gave the results of 11 other unsolicited tests as well! Doing the lot was cheaper than a single test separately. Sometimes the tests that had not been requested were abnormal. That might be a good thing if, for example, a new diabetic patient was identified, but sometimes extra time and effort went into chasing an aberrant result to an unwanted investigation.

The MRC’s randomised controlled trials provided a new way of determining the effectiveness of treatment. Archibald Cochrane took up and publicised the idea while working at the Pneumoconiosis Research Unit in Wales, arguing for its immense potential. Cochrane’s devotion to this cause, and the later publication of Effectiveness and efficiency in 1972, left a lasting mark on health care and the health service.35

Specialisation

The establishment of the NHS coincided with growth in highly specialised fields of medicine and surgery. Techniques that, during the years of war, were being laboriously developed in a very few centres, advanced so far that they were becoming an essential part of a regional hospital service.36 Specialisation, though of great benefit to patients, was not solely a matter of altruistic doctors seeking an ever-deeper understanding of disease. Christopher Booth has suggested that specialisation had three main roots, the most important being the drive of technology. Modern ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery, diagnostic imaging, interventional radiology and minimal access surgery were based almost entirely on the development of instrumentation; the division of general pathology into biochemistry, histopathology, haematology and microbiology was partly related to major differences in the supporting technology. Secondly, individual doctors pushed themselves and their expertise out of enlightened self-interest. In the nineteenth century this led to the development of the single specialty hospitals; the same motivation exists to this day. Thirdly, those in minor areas of medicine sometimes mobilised sympathy for themselves and their patients. The higher their profile, the greater was their access to distinction awards.

The need to provide specialised services, and sub-specialisation, drove an increase in the number of consultants from roughly 4,500 in 1948 to 7,000 by 1960. George Godber said that specialisation had probably not yet gone far enough; specialist skills should be more widely distributed than they were. Yet there was a need to avoid the division of the care of patients between a multitude of specialties, and a risk of failed communication between disciplines.37 The main growth was not in the traditionally glamorous fields, but in anaesthetics, radiology, pathology, psychiatry and, later, geriatrics. There was a shortage of recruits and NHS money was sometimes used to establish university Chairs, improve training and raise status. General medicine and surgery divided into sub-specialties and the officially recognised specialties doubled in number. Cardiology split from general medicine, although respiratory medicine remained a part of the work of the general physician. Special investigative techniques in cardiology, respiratory medicine and neurology were far past the experimental stage and were needed in at least one centre in every hospital region. Such techniques were central to the development of intensive treatment units (ITUs), born in the early 1960s. The infectious diseases were diminishing and there were fewer consultants in that specialty; in the future it was likely that there would be infectious disease units attached to district general hospitals (DGHs). Paediatricians were increasingly concerned with the neonatal period. In 1948 it was considered normal for general physicians to look after the chronic sick and elderly as part of their duties. Now geriatrics was developing and appointments of consultant geriatricians were being made. No longer was a consultant pathologist wise to attempt to handle all four sub-disciplines of haematology, biochemistry, histopathology and bacteriology.

In surgery, operations on the central nervous system, the heart and the lungs were now commonplace and these regional specialties were growing. Rapid advances in cardiac surgery had led to its extension to all the principal thoracic surgical units, previously largely concerned with tuberculosis and bronchiectasis (dilation of the bronchi or bronchioles). Traumatic and orthopaedic surgery were developing, and urology and paediatric surgery were becoming the province of specialist rather than general surgeons.

Some GPs still hoped for their reintegration into hospital work. Others, such as John Fry of Beckenham, were more realistic.38 Much health care was outside hospital, and more could be if there were better access to hospital diagnostic facilities and more support were available for the care of patients at home. That was what was needed, and not nationwide schemes to give family doctors beds in hospitals. Hospitals served many more than were within their walls.

The drug treatment of disease

In 1959 Beecham Research Laboratories discovered a method for the large-scale production of the penicillin ‘nucleus’ and, within two years, was able to prepare several hundred new synthetic compounds. Three seemed useful: phenethicillin was acid-resistant and could be given by mouth; methicillin had to be injected but, being resistant to penicillinase, was effective against penicillin-resistant staphylococcal infections, and helped to control the large hospital outbreaks of infection of the previous decade; and ampicillin had, for a penicillin, the remarkable property of a wide range of effectiveness.39 Griseofulvin was also discovered in 1959 and was the first antibiotic active against fungi that could be given by mouth. It was discovered by ICI but sold to Glaxo because of apparent side effects. Glaxo found that these were temporary and minimal and that griseofulvin could be used to treat fungus infections whether systemic, of the skin or of finger and toe nails. Griseofulvin seemed to protect new skin and nail cells from infection, so, if it was administered long enough, new healthy tissue replaced the old areas of infection. The clinical results were so dramatic that, when cases were demonstrated at a dermatologists’ conference in the USA, the hotel lines were blocked by doctors phoning their brokers to buy shares. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as tetracyclines were found to be highly effective in treating acne, a common and sometimes disfiguring disease, although how they worked was uncertain. In 1960 metronidazole (Flagyl) was introduced for the treatment of vaginal discharge caused by Trichomonas vaginalis.

In the past, the treatment of heart failure had been rest, digitalis and mercury-based diuretics such as mersalyl that was given by injection. This meant hospital treatment or regular visits by the district nurse. The discovery in 1957 of chlorothiazide, the first effective oral diuretic, was probably the most important advance in drug treatment since penicillin.40 People with heart failure could now live a much more normal life, at home, while under treatment. Other more potent compounds of the same group followed rapidly and, in 1965, frusemide was a further improvement.41 The treatment of high blood pressure improved steadily with the introduction of new drugs. Rauwolfia, acting partly as a tranquilliser, was replaced by the oral diuretics, often in combination with ganglion-blocking drugs such as mecamylamine, although these produced constipation, blurred vision and difficulty in urination. Adrenergic-blocking drugs (e.g. guanethidine) had fewer side effects, and early death from severe hypertension was now seldom seen.42 Angina was shown to be relieved by propranolol, a member of a new family of drugs, the beta-receptor blockers, synthesised by James (later Sir James) Black, a discovery commemorated in 2010 by a Royal Mail stamp.43 Propranolol was also effective in the treatment of high blood pressure. To develop one blockbuster drug is remarkable;. to go on, as James Black did, and develop a second one (H2 antagonists) is amazing.

In the past, the treatment of heart failure had been rest, digitalis and mercury-based diuretics such as mersalyl that was given by injection. This meant hospital treatment or regular visits by the district nurse. The discovery in 1957 of chlorothiazide, the first effective oral diuretic, was probably the most important advance in drug treatment since penicillin.40 People with heart failure could now live a much more normal life, at home, while under treatment. Other more potent compounds of the same group followed rapidly and, in 1965, frusemide was a further improvement.41 The treatment of high blood pressure improved steadily with the introduction of new drugs. Rauwolfia, acting partly as a tranquilliser, was replaced by the oral diuretics, often in combination with ganglion-blocking drugs such as mecamylamine, although these produced constipation, blurred vision and difficulty in urination. Adrenergic-blocking drugs (e.g. guanethidine) had fewer side effects, and early death from severe hypertension was now seldom seen.42 Angina was shown to be relieved by propranolol, a member of a new family of drugs, the beta-receptor blockers, synthesised by James (later Sir James) Black, a discovery commemorated in 2010 by a Royal Mail stamp.43 Propranolol was also effective in the treatment of high blood pressure. To develop one blockbuster drug is remarkable;. to go on, as James Black did, and develop a second one (H2 antagonists) is amazing.

Pressurised aerosols were introduced for the treatment of asthma in 1960 and rapidly became popular. If used too often they could be toxic, and patients sometimes overdosed instead of calling for medical help.44 A GP who found a young asthmatic dead with an inhaler in her hand did not forget the experience. To the surprise of doctors, deaths from asthma rose. A fivefold increase led to a warning in 1967 about the possible dangers of inhalers. Often those who died had never received corticosteroid treatment that could have been life saving; sometimes, incorrectly, doctors had administered sedatives.

A new drug, indomethacin, for the treatment of arthritis, rheumatism and gout, was released in 1965. Although no panacea, it was helpful in the relief of pain, inflammation and stiffness.45 Immunosuppressive and cytotoxic drugs developed for cancer found uses in dermatology, because their action on rapidly dividing cells could control conditions such as psoriasis, pemphigus and systemic lupus erythematosus.

After small trials of oral contraceptives in 1959, the Family Planning Association undertook two large field trials to assess the use of Conovid and Anovlar. The results were good and the products were approved for clinic use.46 Lower dose preparations of the oral contraceptives were later introduced. By 1968 roughly a million women were using oral contraception. In the early 1960s, an alternative became available: intrauterine contraceptive devices that were shown to be highly effective and comparatively safe.47

Drugs for the treatment of diseases of the mind came on the market with increasing frequency. Amphetamines had been available since 1935 and, until the late 1950s, were considered relatively non-toxic, rarely addictive and without serious ill-effects. It then became clear that many people were taking far more than therapeutic doses and were using subterfuge to obtain them. Side effects including psychosis were observed. Weaning patients off amphetamines and ‘purple hearts’, an amphetamine-barbiturate mixture, was difficult.48 An alternative group of drugs, the benzodiazepines, came into use. It included chlordiazepoxide (Librium), diazepam (Valium) and nitrazepam (Mogadon). In the laboratory these drugs calmed aggressive animals; in humans they reduced anxiety, though with some tendency to produce addiction. Caution and short-term use were recommended, for they made people sleepy, and the additive effect of alcohol could be dangerous. 49 In 1958– 1960, drugs for the treatment of depression became available: first the monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and then tricyclic drugs such as amitriptyline and imipramine. The treatment of even fairly severely depressed patients became possible without admission to hospital, but the drugs might cause a flare-up of schizophrenia and could not entirely replace ECT.50 The difficulty of designing good clinical trials made it hard to determine the best way to use the drugs and some had unexpected side effects. Severe headaches after cheese sandwiches seemed unlikely to be related to monoamine oxidase inhibitors, but this was the case, and the chemical interaction responsible was identified. Interaction of drugs was a growing hazard; the thiazide diuretics increased the potency of digitalis if the patient became depleted of potassium, and phenylbutazone increased the response to anticoagulants. There was every reason to reduce the risk by prescribing as few drugs as possible for any single patient.51

Better anaesthetic agents made for easier induction of anaesthesia, safer operation and speedier recovery. However, it was now usual to give one drug to produce unconsciousness, another as a pain reliever and a third to relax muscles to make it easier to operate. This cocktail of drugs made the classic signs of the depth of anaesthesia difficult to interpret, if not useless. Cases were reported of patients remaining conscious during surgery if the balance of drugs was wrong. Patients had no way of signalling the fact because muscle relaxants paralysed them, yet they suffered extreme pain and could recall staff conversations during the operation.

Adverse reactions

Old, if cynical, advice to medical students had been to use new drugs while they still worked. That was now a dangerous strategy. Penicillin produced allergic reactions. Tetracyclines, considered to have few side effects other than loosening bowel motions, were found to turn children’s teeth yellow. Barbiturates, used as sleeping tablets, proved addictive and many family doctors imposed a voluntary ban on their prescription. Was sufficient advice available from independent clinical pharmacologists to put manufacturers’ claims into perspective? The pharmaceutical industry spent a great deal of money, took big risks and occasionally produced products of outstanding value. There were vast improvements and economies in medical care. But within the industry were firms with a high sense of duty and others with a high sense of profit.52 Were drugs released on the market prematurely?

The thalidomide disaster brought professional anxieties to a head. It was released in Germany in October 1957, where it was available over the counter; when it was released in the UK in 1958, it was available only on prescription (in the USA approval was delayed). It was an excellent drug for inducing sleep and an overdose seldom killed – the patient slept soundly and then woke up. Thalidomide was even promoted as safe around a house where there was an inquisitive infant. Then, with little warning, it was found to produce limb deformities in the unborn child. At a paediatric conference in November 1961, it was reported that there was a possibility that, if taken in pregnancy, thalidomide might have harmful effects on the developing embryo. It was rapidly taken off the market. Defects of the hands, the long bones of the arms and legs, and oesophageal abnormalities were rapidly reported worldwide, but the number of cases seen in any one clinic was extremely small. Registers of congenital malformations, kept for research purposes in Birmingham and London, provided clear evidence of an epidemic. Medical records were not always available; some had been destroyed. Sometimes people had taken tablets prescribed for friends and relatives, or tablets left over from a previous illness. The reaction was rapid. Assessment centres were established for the sufferers, voluntary agencies offered help, and parents’ associations were formed. The total number of cases in Britain who survived long enough to be recorded was about 300, far less than in Germany where the problem had first been reported.53

There were issues of principle at stake. Fifty years earlier, Sir William Osler had said that the main distinction between humans and the higher apes was the desire to take medicine. Doctors now had to be wary of their instinct to help by reaching for the prescription pad. No systems existed for the early detection of congenital defects, to ensure that new products were safe and efficacious, or to track adverse drug reactions so that the medical profession could be informed. The call for an independent organisation to examine new drugs, particularly for effects on the fetus, intensified.54 SMAC suggested that there was a need to assess new drugs before release, detect adverse effects rapidly and keep doctors informed about the experience of drugs in clinical practice. After consultation, the Committee on Safety of Drugs was formed, chaired by Sir Derrick Dunlop.55 It devised a system of checking new drugs that came into operation from January 1964. Drugs then passed through three stages of assessment: laboratory toxicity trials; clinical trials on humans (such as the MRC trials of the anti-tuberculosis drugs); and ‘post-marketing surveillance’.56

There was still no system to ensure the identification of a rare effect that might arise after general release of a new drug, perhaps only once in a thousand patients. The Committee decided to rely on voluntary notifications and the ‘yellow card’ scheme was introduced. An estimate of drug usage was obtained from the central prescription pricing bureau and from trade sources. There were two limitations to the yellow card scheme: first, reporting was incomplete and the degree of incompleteness was unknown and variable; second, it was not possible to determine how many patients had been given a drug, or their age and sex. The incidence of a reported reaction could not be compared with its normal incidence in the sick or those who were healthy. Occasionally adverse reactions in a preparation not of vital importance led to its withdrawal, for example, a slow-release form of an influenza vaccine. Sometimes there were ‘reactions’ that were likely to be coincidental, or which, though probably genuine, were outweighed by the undoubted benefits of the drug. In these cases, a warning was issued but the drug was not withdrawn.57 This group included monoamine oxidase inhibitors, pressurised aerosols for asthma and oral contraceptives.

Radiology and diagnostic imaging

Advances in nuclear medicine, and the tracking of isotopes, depended on technical advances in detectors. Rectilinear scanners were developed in the 1950s and allowed the source of radiation to be located and mapped, line by line. The process was slow; in the mid-1960s a liver scan could take up to an hour and the definition of the pictures was poor. Rectilinear scanners were made obsolete by the development of gamma cameras, the first prototype of which was displayed in Los Angeles in 1958.58 As the quality of gamma cameras improved, and they were coupled to computer systems, they were used to scan the lung, brain, heart, bones, liver and thyroid, providing new information to improve diagnostic accuracy.

The first alternative to radiation in the production of body images was ultrasound, the offshoot of wartime sonar. Ultrasonic equipment had been used by industry for some years to detect flaws in metal. Ultrasonic sound waves were propagated as a beam, penetrated body tissues and, because some were reflected, could be used to create images. In the 1950s a number of dubious clinical claims were made for the technique. The development of a clinically workable tool was dominated by a few individuals, such as Ian Donald in Glasgow, and workers in the USA and Sweden. In 1958 Donald published the results of investigating 100 patients, mainly gynaecological and obstetric cases. Ovarian cysts, tumours and fibroids could be seen.59 Twins were also diagnosed.

Endoscopy

Between 1954 and 1970, three inventions, all introduced by Harold Hopkins from Imperial College, changed the face of endoscopy and paved the way for minimally invasive surgery.60 For a century endoscopes had been rigid metal tubes and it had only been possible to examine the inside of the oesophagus, rectum and colon, lung or bladder until one came to a bend. In any case it was an uncomfortable procedure and much skill and psychology was needed. That all changed. First came the flexible light guide made up of bundles of glass fibres each coated with glass of a different refractive index along which light of unlimited brightness could be guided into any body cavity. The second advance was Hopkins’ revolutionary telescope. Instead of using tiny glasses separated by spaces of air, Hopkins used air lenses separated by rods of glass. Needing no tubular metal to keep the lenses apart, the entire width of the telescope was available for the transmission of light. Furthermore, because the rods could be held steady, it was possible to grind and coat their surfaces to a new order of accuracy and the rod-lens telescopes had the precision of a microscope. The powerfully illuminated images amazed the older generation of endoscopists. The third invention was to wind the glass fibres on a wheel and glue them together at one point, at which they were cut. Except at this point the fibres were enclosed in a loose sheath so they were entirely flexible. Where they were cut the fibres coincided with each other so that an image put in at one end came out at the other in dots, like the image of a newspaper photograph. A new family of flexible endoscopes quickly emerged, making it possible to perform gastroscopy, colonoscopy, bronchoscopy, cystoscopy and laryngoscopy without danger or great discomfort. They were steadily improved, so that comparing newer with older ones was like comparing a jet with a piston engine. Through these instruments it was possible to take biopsies, cut strictures, remove stones, destroy small tumours and stop bleeding with diathermy or laser.

Infectious disease and immunisation

The decade saw the conquest of poliomyelitis and the reduction of cases of diphtheria to a trickle, although small localised outbreaks continued to occur, mainly among people who had not been immunised. The burden of infectious diseases and the need for beds were reduced. The waning of the great killing diseases led to a false sense of security and masked their continuing evolution.61 Few doctors or nurses were now trained to handle them. There was ignorance and an assumption that most of the problems had been solved. Yet food-borne infection increased. The exotic viral haemorrhagic fevers were recognised for the first time; in 1957 a previously unknown communicable disease was reported from Germany. Twenty-seven workers preparing polio vaccine in Marburg developed headache, fever, rash and haemorrhages after contact with African vervet monkeys. Seven patients died of ‘Marburg fever’ and no form of treatment seemed effective.

Measles vaccine had been under development for several years and was in use in the USA. After a trial by the MRC, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation decided in 1965 not to launch a general vaccination programme but to make the vaccine available to GPs wishing to use it. Measles epidemics were a bane of general practice; every second year there would be dozens of calls to miserable and sick children who needed careful supervision because of chest and ear infections, for which antibiotics were frequently prescribed. Some GPs immediately began to immunise ‘their’ children, seeing a benefit to patients and a reduction in their work. By 1967 their hunch had been validated by a further MRC trial that also revealed the large number of complications, the cost of the antibiotics prescribed, the 5,000–10,000 hospital admissions annually and the deaths that occurred. Routine vaccination against measles was recommended.

The introduction of the injectable Salk polio vaccine reduced the number of cases and deaths, but protection was not complete. In 1959 there were 591 cases of paralytic polio in unvaccinated people, but there were also 40 in people who had received an apparently complete course. The MRC organised a trial of a new live attenuated vaccine developed by Albert Sabin.62 Theoretically this could be expected to give better protection, and it did. In 1962 oral polio vaccine was introduced into the routine immunisation programme. The same year, Tom Galloway, MOH of West Sussex, pioneered a new approach to the organisation of immunisation programmes. The local authority computer was programmed to use the information collected by health visitors who called to see newborn infants, to summon them to clinics or to their GP’s surgery at the appropriate age.63 A rapid rise in the immunisation rate was achieved and other local authorities soon adopted the system. West Sussex applied the same technique to cervical cytology, and Cheshire to child surveillance.

A major influenza epidemic, Asian ‘flu, occurred in 1958– 1959. Influenza subtype A H2N2, appeared in the east in 1957 and spread rapidly as a pandemic to the UK. WHO estimated deaths worldwide as about 2 million. The author, then a depot medical officer, cared for 300 cases among 700 young soldiers, a maximum of 100 being in bed at any one time. Treatment was purely symptomatic and all recovered, except one recruit who was found to have leukemia.

Smallpox entered the country from time to time: in 1962, there were five small outbreaks of smallpox, with 62 indigenous cases introduced by travellers from Pakistan, some of whom had presented false vaccination certificates. There was a rush for vaccination: local authority clinics vaccinated more than 3 million people and there were queues outside GPs’ surgeries. It was impossible to reassure people that, outside the areas of infection, the risks were virtually non-existent. SMAC considered the smallpox vaccination programme and decided that, if there were no basic immunity in the population, control of epidemics might not be easy. It recommended continuation of the routine smallpox vaccination programme.64

Deaths in England and Wales from infectious disease

|

Tuberculosis |

Diphtheria |

Whooping cough |

Measles |

Polio |

|

|

1948 |

23,175 |

156 |

748 |

327 |

241 |

|

1957 |

4,784 |

4 |

87 |

94 |

226 |

|

1958 |

4,480 |

8 |

27 |

49 |

154 |

|

1959 |

3,854 |

0 |

25 |

98 |

87 |

|

1960 |

3,435 |

5 |

37 |

31 |

46 |

|

1961 |

3,334 |

10 |

27 |

152 |

79 |

|

1962 |

3,088 |

2 |

24 |

39 |

45 |

|

1963 |

2,962 |

2 |

36 |

127 |

38 |

|

1964 |

2,484 |

0 |

44 |

73 |

29 |

|

1965 |

2,282 |

0 |

21 |

115 |

19 |

|

1966 |

2,354 |

5 |

23 |

80 |

22 |

|

1967 |

2,043 |

0 |

27 |

99 |

15 |

Source: On the state of the public health – annual reports of the Chief Medical Officer (1948 to 1967)

Tuberculosis remained a major problem, although notifications and deaths were steadily getting fewer. Routine Heaf tests at the age of 13 showed the extent to which asymptomatic infection was occurring in the community, and a progressive reduction in the number of positive tests was clear evidence of reduced spread. The effectiveness of treatment, particularly in early cases, was an added reason for identifying patients as rapidly as possible, for treatment quickly reduced their infectivity, breaking the chain of spread. Well-organised domiciliary treatment was practicable, effective and safe for family contacts.65 As the incidence of tuberculosis fell, mobile miniature radiography units picked up fewer cases of tuberculosis, but cancer of the lung was occasionally diagnosed in this way. Because mobile miniature radiography delivered a large radiation dose, their continued use was questioned. The Public Health Laboratory Service (PHLS) continued to grow, and the introduction of tissue-culture led to an expansion of its work in virology. It studied the development of hospital-acquired infection and of food poisoning, and became increasingly involved in the epidemiology of infectious disease.

Venereal disease

In 1955, coincident with the increase of immigration, figures for gonorrhoea and non-specific urethritis began to rise and, by 1962, had passed the 1939 level. Granada Television reported on the growing health hazard, interviewing a man who said he had been infected by ‘a debutante and a prostitute’ who had placed too much faith in a regular check-up.66 Three causes were suggested: immigration; homosexuality; and, to a small extent, promiscuity among the young.67 Syphilis seemed controllable, by penicillin and contact tracing, even though extramarital sexual intercourse was coming to be regarded by many as a normal and permissible activity. However, gonorrhoea was less amenable.68 In women there were often no symptoms to bring them to the clinic. Just under half the male cases were from the indigenous population; a quarter were men infected abroad; and a quarter West Indian men. Most of those from the West Indies were infected in the UK, usually by ‘promiscuous women’. Indeed, figures from Holloway Prison showed that about a third of the prostitutes in prison were infected. A third of all infections in women were among those between 15 and 20 years of age.69

Surgery

Information on the work of the hospital service was now available from the Hospital Inpatient Enquiry, a 10 per cent sample of the admissions to all hospitals in England and Wales, other than those for mental illness and deficiency. Outpatient attendances and admissions were steadily increasing. The commonest cause of admission up to the age of 5 years was for removal of tonsils and adenoids (Ts and As). From 5 to 14 years, appendicitis came second to Ts and As. From 15 to 29 years, head injury and appendicitis were commonest for men and, excluding midwifery, appendicitis and spontaneous abortion for women. Men between 30 and 70 years of age were admitted mostly for hernia, duodenal ulcer, cancer of the lung and prostate disease. Women suffered from disorders of menstruation and prolapse, and leg fractures in the older age groups.70

The length of stay in hospital continued to shorten. The Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, faced in 1960 by lengthy waiting lists, adopted Farquharson’s technique and established a special team to treat people with hernia and varicose veins as outpatients. Patients went home a few hours after operation and, although the hospital offered to provide after-care, the GPs were more than willing to take this over. Initial anxieties vanished and, because of the noise, poor facilities and irksome discipline, many patients were pleased to leave hospital rapidly. Waiting lists fell, the cost of treatment was probably lower, and the results seemed quite as good.71 By the end of the decade it was seen that, with proper selection of patients, suitable accommodation and organisation, and good communication with GPs and community services, more patients could be dealt with as outpatients or on a day basis. Some now believed that outpatient surgery and day patient facilities should be part of any modern hospital, and that the ratio of operating theatres to beds should be increased. Advice on the design and running of day units was published.

Orthopaedics and trauma

Following the work of Danis and Müller, Swiss orthopaedic surgeons formed a group to study the value of fixation and compression of fractures, and to undertake experimental work. This group, the AO (or Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen), began to collaborate with the Swiss precision engineering industry, which produced the components emerging from research. An educational programme was created to teach the techniques, John Charnley being among those attending.

The opening of the M1 motorway in 1959 led to a new style of driving and a new pattern of serious injuries. On urban roads, pedestrians were the main victims. On country roads, it was motorcyclists. On the motorways, the vast majority were occupants of cars. Injuries, the chief killer between 1 and 35 years of age, were more frequent, more severe, occurred throughout the 24 hours, and were widely dispersed geographically. In 1966, Dr Ken Easton, realising that people were dying unnecessarily in serious road accidents because blood loss was not treated and the airway was not secured, started an organisation of GPs who were prepared to offer immediate care. This later became the British Association of Immediate Care Schemes (BASICS). Seat belts were made mandatory in new cars in 1967, and it became an offence for someone to drive with over 80 mg of alcohol per 100 ml of blood.

Surgeons knew how massive blood loss could be and that very large transfusions might be needed. The treatment of serious and multiple injuries required immediate blood replacement, diagnosis, ventilation, suction, blood volume studies, metabolic checks, radiology and surgery. A full team was necessary, available only at special centres. SMAC set up a group to study accident services, chaired by Sir Harry Platt; the group thought that the accident and emergency (A&E) units should be reduced substantially in number, so that staffing was always adequate.72 A BMA committee also considered the problem in 1961. It examined experience in Birmingham, Oxford and Sheffield. A three-tier system was proposed, with a central accident unit usually attached to a teaching hospital, other accident units in selected hospitals, and support from peripheral casualty services.73 There was wide agreement that effective treatment of injuries required experience and good facilities that were well organised. A country-wide accident service organised regionally was now necessary, but such a service never became an agreed NHS policy.74

John Charnley, funded by the Manchester RHB, made an unsurpassed contribution by developing the surgical, mechanical and implant techniques of hip replacement. He added two elements to McKee’s operation. He concentrated on engineering issues, designing a low-friction arthroplasty using a small metal femoral head articulating with a plastic insert in the acetabulum. His first attempts used stainless steel for the head and Teflon for the pelvic component. The wear rate proved unacceptably high – the joint would fill with fine particles of Teflon debris and the femoral head might wear through the cup. With the engineers at Manchester University, he explored the engineering and lubrication problems, realised that a small femoral head gave rise to less friction than a large one, and switched to ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. This low-friction arthroplasty proved successful.75

His second contribution, in 1962, was the introduction of polymethylmethacrylate cement to distribute the stress from the metal components evenly over the bone. His results steadily improved, and he was not a person to seek to make private profit out of his work. An impressive speaker and writer, he had data to back his claims and the best technology then available. As he improved the technique, he set about training others in it. Surgeons turned their attention to the knee. By the early 1960s, three different prostheses were in use, all cobalt-chrome hinges attached to stems running into the bone cavities of the tibia and femur, in the lower and upper leg. They were not widely used because the early results were not encouraging and, if the operation failed, revision was difficult.

Cardiology and cardiac surgery

Disorders of heart rhythm commonly cause death because, when cardiac arrest occurs, oxygen lack rapidly causes brain damage. Prompt restoration of the circulation is necessary: if any attempt was made to restart the heart, the method was to open the chest where the patient lay to massage the heart. Following the development of closed-heart defibrillation, external cardiac massage was developed at the Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.76 Successful resuscitation, though rare, encouraged a more energetic approach to cardiac arrest. With these new techniques of monitoring and resuscitation, coronary care units were developed.77 In 1963, Toronto General Hospital reported the centralisation of patients in a unit with special provision for early detection and treatment of disorders of heart rhythm and cardiac arrest. The improvement in survival was far from spectacular, but a trend was established.78 As a result, many of the sickest patients in a hospital were moved to a new facility that required nursing staff with new skills. The knowledge needed by intensive care nurses, and the speed with which they had to take decisions, made frequent staff changes impracticable. The nurses developed the necessary expertise and were often able to guide young doctors in the diagnosis and management of cardiac arrhythmias. Although deaths from heart attacks occurred soon after the onset of symptoms, the delay before admission was, on average, nearly 12 hours. In 1966, Pantridge, at the Royal Victoria Hospital Belfast, introduced a mobile intensive care unit – a specially equipped ambulance – to provide skilled care to people on their way to hospital.79 Mouth-to-mouth respiration and external cardiac massage began to be taught to the public by the first-aid organisations, with professional approval.80

Patients with a slow heart rate from heart-block had a high death rate, a low cardiac output, and were unable to meet the demands of exercise or emotion. Electronic developments, and the ability to insert a tube or wire safely into the heart, led to the development of pacemakers. Electrical impulses were used to restore a normal heart rate. The first pacemakers were external and uncomfortable for the patient, but in 1960 an implantable unit was developed and from then on pacemakers developed rapidly. Improvements in technique, and the development of ‘demand’ pacemakers that allowed variable rates of pacing, cut the mortality and enabled increasing numbers of patients to live a near-normal life with a greater sense of wellbeing. Some patients with good heart function could even return to work, and the mortality rate for patients with complete heart-block was greatly reduced.81

More effective surgery within the heart became possible with the introduction of heart-lung bypass techniques from the USA. Accurate diagnosis, the surgical skill to correct hidden and undiagnosed abnormalities, and good teamwork were the keys to success.82 Characteristically, a procedure had a high mortality when first introduced, but this fell rapidly as experience was gained. From the patient’s point of view, there was often a case for delay until techniques improved and risks were lower.83 It was essential to have a well-trained team that could carry out successful perfusion, not only under ideal conditions but also when things went wrong. The Hammersmith Hospital reported a series of cases in which the heart-lung machine was used in ventricular septal defect. Paul Wood, at the National Heart Hospital, said that 85 per cent of cases of congenital heart disease were now operable. Though the risks of operation on septal defects between the left and right side of the heart were falling, morbidity from complications such as cerebral embolism was substantial. Operations were also developed to replace damaged heart valves that either leaked or were blocked. A ball valve designed in the USA by Starr made possible the replacement of the mitral valve, and later of the aortic valve as well. Initially the mortality rates were up to 20 per cent, and replacing more than one valve increased the mortality.84 Donald Ross, at the National Heart Hospital, was the doyen of aortic valve grafts, also successfully using the patient’s own pulmonary valve to replace the more important aortic valve.

Direct surgical attack on blocked coronary arteries now seemed within reach, but a clear picture of the arteries was required before this was possible. Coronary angiography, injecting contrast medium into each artery, was developed at the Cleveland Clinic and introduced to the UK.85

Narrowing of the carotid artery had long been known to be one cause of strokes. Surgical treatment was increasingly used for patients who had transient symptoms suggesting impaired circulation to the brain – difficulty with speech or vision, or transient weakness.86 In the USA, the operation rapidly became popular but a more conservative approach was adopted in the UK and soon proved more successful.

Renal replacement therapy

The nature of renal disease was changing. Nephritis after streptococcal infection was becoming rare; yet there was no reduction in the numbers developing chronic renal failure. Steroids had completely changed the picture in another kidney disease, nephrosis. There were major advances in the treatment of both acute and chronic renal failure. Intermittent renal dialysis was in use in the USA in the early 1950s, and in Leeds from 1956:87 the patient’s blood was passed through coils immersed in special solutions into which impurities passed, before it was returned to the body. Over the next four years, several other units that could treat acute renal failure were established, mainly in teaching hospitals. The chief problem was that clots formed in the veins, which could not be used again. It was technological development that altered the nature of the care available. In 1960, Scribner demonstrated an implantable arterio-venous shunt that could be used repeatedly and, although the shunts were not trouble free, there was no longer a temptation to dialyse for a long time to delay the need for the next treatment. The combination of the shunt and better dialysis equipment that required no donor blood to prime it raised the possibility of treating chronic renal failure on a considerable scale. The procedure was on probation in the USA from 1960 to 1962, when it was recognised as a considerable advance. Clinical opinion in the UK was divided. Douglas Black, in a Lancet editorial in 1965, said that such programmes made exacting demands on skills, time and money, and their claims should be compared with other forms of intensive care. The debate was confused by the emergence of hepatitis as a problem of care internationally. Between 1965 and 1971 there were some 200 cases in 12 units in the UK, for example, an outbreak in Douglas Black’s unit at the Manchester Royal Infirmary which affected eight staff with one death. Taking the outbreaks together, 12 patients and six staff died. Some patients were found to be hepatitis carriers, and cross-infection was all too easy. Antibiotics were no answer. Patient care had to become more hygienic and barriers were needed to prevent the transmission of infection. The Ministry set up an expert group chaired by Professor Sir Max Rosenheim, of University College Hospital, to consider dialysis, plan development and arrange the supply of dialysers.88

Demand outpaced the availability of treatment, and clinicians and patients were indignant; some young people were now being treated and, as a result, were leading an active and productive life; should they be allowed to die?89 A further technical development largely replaced the Scribner shunt and made repetitive dialysis available to virtually everyone.90 A surgically created interior arterio-venous fistula between the radial artery and vein was then developed by Cimino and Brescia in 1966. Unfortunately, money and trained staff were limiting factors and it was impossible to offer treatment to all who could benefit from it. Renal medicine was one of the first specialties to face the ethical problems of selection of patients and the economic problems of provision. Exceptionally, government provided money specifically for renal dialysis – £10 million per annum. Plans were made for 10–20 centres and also for home treatment. Nationwide, only 70 patients were receiving treatment in 1965, but between 1967 and 1971, units opened in each region.

Renal transplants were undertaken in the early 1960s in patients who were gravely ill, using unrelated kidneys and attempting to suppress rejection by total body irradiation or drugs that had been effective in animals. There were a few successes. Successful transplantation required good surgical techniques, for example, a reliable way to join blood vessels, and growth in knowledge about immunology and tissue rejection. The first liver transplant, in March 1963, was performed by Thomas Starzl in Colorado. The patient, a 3-year-old, died shortly after. Results of transplantation improved with the introduction of azathioprine in 1965, and transplantation emerged from the experimental stage.91 Britain was slow in developing a comprehensive policy for handling renal failure; a transplant service became essential, for without it enormous sums would be spent on dialysis. Yet transplantation was possible only on the basis of a renal dialysis service. Who should be treated and how were decisions to be taken? A serious ethical difficulty faced doctors looking after patients with irreversible renal failure. Some 6,000 died annually, half between the ages of 5 and 55, and both dialysis and renal transplants offered over a 50 per cent chance of surviving a year or more. Was the selection of patients, a life or death decision, best left to the consultant?92 Most units, faced with the impossibility of treating more than a few of those in need, rejected elderly people and people with diabetes in favour of “happily married patients with young children, who were reliable, stoic and endowed with common sense”. Some preferred to take patients as they presented if a vacancy on the treatment programme was available.93

Experimental transplants of the pancreas, lungs, heart and liver were undertaken in animals. The difficulties were greater than with the kidney, where renal dialysis could maintain the recipient in good health. That was not possible for somebody dying of heart or liver disease. The transplanted organs were also harder to maintain in good condition.94 Because of the wider use of organ transplantation, the Human Tissues Bill was introduced in 1960 to allow, subject to the consent of relatives, other parts to be removed (e.g. skin, arteries and bone).95 Bone marrow transplants began on an experimental basis. It was found that, after lethal whole-body doses of X-rays that destroyed existing lymphoid and myeloid cells, grafts from donors ‘took’. After an accident with a nuclear reactor in Yugoslavia, several physicists were treated in this way. Aplastic anaemia (failure of the bone marrow to produce blood cells) was also treated by bone marrow transplantation. However, immunological problems remained and, when tissue typing and matching was imperfect, the graft might attack the host, even if the danger of the host rejecting the graft was overcome.96 Liver transplantation was pioneered in Denver in the early 1960s. The path to heart transplantation in humans was opened by workers such as Shumway at Stanford, who developed the surgical technique and showed that immunosuppressive agents would prolong the period of graft survival. In December 1967, Professor Christiaan Barnard, in South Africa, replaced the heart of a 55-year-old man, who subsequently died, with that of a road accident victim. Four further heart transplantations were carried out in the next few weeks, arousing worldwide interest.

Neurology and neurosurgery

With the growth of transplantation, determining the time of death of potential donors became increasingly significant. The absence of respiration or a heart beat was no longer enough, for life could be prolonged by the ventilators and organ support systems that were being developed. Removal of organs for transplantation could not be undertaken until it was clear that the body could no longer function as a unified system. It was found that, when the integrating mechanisms in the brain stem failed, recovery was impossible and body dissolution began to take place. Mollaret, a French worker, identified this condition as ‘coma depassé’ in 1962 and, over the next few years, many industrialised countries developed and published criteria of brain stem death.

The only treatment available for Parkinson’s disease had been brain surgery, for example, pallidectomy. A major breakthrough began when workers in Austria discovered that, at post-mortem, the basal ganglia of patients with Parkinson’s disease were depleted of dopamine. Infusions of dopamine helped sufferers, but it did not work by mouth because it could not pass the blood-brain barrier. However, in 1966, Cotzias, working in New York, showed that a chemical precursor, levodopa, when administered in large doses, relieved symptoms substantially. For the first time a biochemical mechanism had been discovered for a major neurological condition. More important, it was possible to improve the situation somewhat, and the drug industry became more interested in neurological disease. The management of epilepsy was also improved with the introduction of sodium valproate.

Ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery

Routine hearing tests in childhood were introduced. The hearing aid manufacturers introduced innovative behind-the-ear and spectacle aids that were much less conspicuous than the body-worn models. Such aids became available through the NHS in the late 1960s and remain the commonest type in use.

Much deafness was the result of the inability of the small bones in the middle ear to transmit sound. Operations were developed, often overseas, to improve the ability to conduct sound; for example, surgical reconstruction of the middle ear ossicular chain. In 1963 William House, working with neurosurgeons in Los Angeles, developed a new translabyrinthine approach to the internal auditory canal, for the removal of tumours in and around the auditory nerve (acoustic neuromas). Neurosurgeons had been treating these tumours, but the introduction of the operating microscope made new operative techniques possible. The operating microscope was also used in surgery on the nose and larynx.

Ophthalmology

The application to the eye of drugs such as steroids, antibiotics, and beta-blockers in glaucoma saved sight on an enormous scale. Lasers, developed in the early 1960s, rapidly found an application in the treatment of eye disease, replacing older techniques, improving the success rate and reducing the duration of treatment. Coupled with an ophthalmoscope, they could be directed at any part of the internal eye and used for treating detached retina and vascular abnormalities.97 After early disappointments, lens implants using purer plastics and lenses with loops to aid attachment led to an improvement in the results achievable, but the operation usually chosen was lens extraction followed by the use of high-powered spectacles or contact lenses.

Cancer

The mortality from cancer exceeded 100,000 for the first time in 1962 and, even in children, it was becoming a more significant cause of death. Supervoltage radiotherapy was now well established, and as equipment improved it was possible to deliver the dose more accurately to the important area. Computing was applied to treatment planning. Increasingly radiotherapists became aware of what they could cure, and what they could not. Radioactive implants, a long-standing form of treatment for some circumscribed tumours, became more sophisticated.