Chronology

1998

Background

Kyoto Protocol (December 1997)

Digital TV

FTSE reaches 6000

Human Rights Act

NHS events

Green Paper – A First Class Service

Bristol cardiac surgery scandal

Information for Health strategy

NHS Direct

Acheson Inquiry into Inequalities in Health

da Vinci robotic equipment (USA)

1999

Background

Introduction of the Euro

First elections for Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly;

Irish power-sharing agreement.

NATO action in Kosovo & Serbia

Indictment of President Clinton

Paddington train disaster

Disruption in East Timor

NHS events

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) established

Nurse shortage; substantial pay award.

Royal Commission on Long-Term Care of the Elderly

White Paper – Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation

Abolition of fundholding

Establishment of Primary Care Groups

Alan Milburn Secretary of State

2000

Background

Millennium Dome/London Eye

Queen Mother 100

Wikipedia

Fuel tax protests

Hatfield train crash

Israel/Palestine Intifadah

Collapse of dot.com/tech shares

NHS events

‘Breakfast with Frost’ – PM increases NHS spending

Shipman murders

Phillips Report into BSE

White Paper –The NHS Plan

NHS Walk-in Centres

White Paper – Reforming the Mental Health Act

NHS/private sector co-operation

Commission for Healthcare Improvement (CHI)

2001

Background

Bush US President/US recession

Human genome sequenced

Foot and mouth epidemic

Labour landslide election victory

Globalisation riots

9/11terrorist attack on World Trade Center

Afghanistan conflict

iPod launched

NHS events

Organ retention report

Health and Social Care Act (2001)

Kennedy Report on Bristol cardiac surgery

White Paper – Shifting the Balance of Power

Hospital ‘star’ system

Wanless preliminary report on NHS finance

2002

Background

Euro legal tender in 12 countries

Death of Queen Mother

NHS events

National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Act 2002

Establishment of Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC)

Devolution day – 28 special health authorities (SHAs) replace health authorities

Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) established

Budget funding increase & Wanless Review

NHS Foundation Trusts proposed

2003

Background

War with Iraq

London congestion charge

Picture messaging

NHS events

John Reid Secretary of State

Tobacco advertising banned

GPs’ and consultants’ contract

Health and Social Care (Community Standards) Act

Agenda for Change pay system launched

Building on the Best (patient choice)

2004

Background

10 further nations join European Union

Asian tsunami

Facebook launched

NHS events

Payment by results

First Foundation Trusts

Choosing Health – Public Health White Paper

Healthcare Commission

Modernising Medical Careers (reform of senior house officer (SHO) grade)

2005

Background

Third Labour administration

London terrorist bombings

New Orleans Katrina Flood

Pakistan earthquake

NHS events

Creating a Patient-led NHS

Expansion of nurse and pharmacist prescribing

Patricia Hewitt Secretary of State

2006

Background

Israel/Hezbollah conflict

Stern Report on global warming

W2.0 – YouTube

NHS events

Hospital star/league tables abolished

Our Health, Our Care, Our Say – Community Care White Paper

Better Research for Better Health

SHAs reduced to 10, PCTs reduced 152

Tony Blair speaks on personal responsibility for health

2007

Background

Bulgaria & Romania join EC

Gordon Brown Prime Minister

iPhone launched

Bali meeting on Climate change

Northern Rock bank collapse – sub-prime mortgage crisis

NHS events

Alan Johnson Secretary of State

Smoking in public places banned

Framework for Action (Lord Darzi)

NHS funding falls

Changes in British Society

The decade opened and closed with Labour in power and the NHS in financial crisis, in spite of the greatest increase in expenditure the NHS had ever seen. The economy was sound for most of the decade. The UK, as many other countries, experienced terrorism, often fuelled by radical Islamic influences. The devastation in New York (9/11), atrocities in Spain and the London Underground, and the Iraq war cast long shadows. Following the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, climate change and carbon emissions became an international issue without significant achievement. Globalisation, the pressures of the European Community and the digital revolution were driving changes. The introduction of the Euro in 1999 led to debate on our place in Europe, and the European constitution. To bring Britain in line with the Community, ambulances changed colour from white to an eye catching yellow.

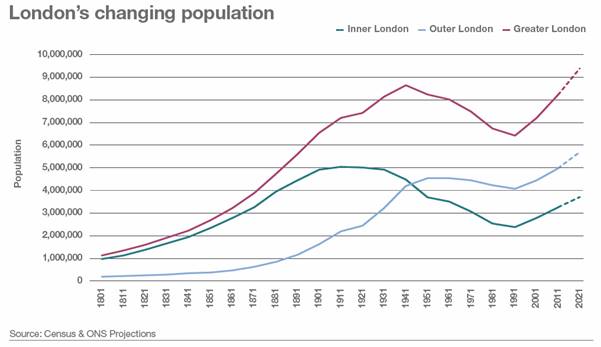

Population movement increased. First London and then the whole country experienced an influx from the European Union. Tens of thousands of young French came. Even before the EC expanded, many from Eastern Europe and especially Poland arrived, filling jobs that the indigenous population did not want. Over a decade, around a million people came. Local authorities complained of the pressure on their services. Retired English travelled to France and Spain for the quality of life. Emigration from the UK increased steadily to nearly 200,000 in 2006. Public reaction to economic migration and asylum seekers changed the political landscape throughout Europe – the UK Independence Party (UKIP) had been founded in 1993. Some migrants came from areas with a high prevalence of AIDS, tuberculosis and hepatitis B. While Bevan explicitly believed that the NHS should be available to everyone, resident or visitor, government now said that it should not be free of charge to those who did not live in the UK. Front-line staff had little time or inclination to ask patients too many questions.

How do we distinguish a visitor from anybody else? Are British citizens to carry means of identification everywhere to prove that they are not visitors? For if the sheep are to be separated from the goats both must be classified. What began as an attempt to keep the Health Service for ourselves would end by being a nuisance to everybody. Happily, this is one of those occasions when generosity and convenience march together.

(In Place of Fear, chapter 5, Bevan, 1952)

The World Health Organization’s 20-year plan to bring ‘health for all’ failed. More than 2 billion people had no basic sanitation. The European Region’s Health for All, equally ambitious, was in tatters.1 The campaign for the reduction of third world debt made only limited progress, and poverty, famine, wars and the AIDS crisis seemed worse day by day.

The north/south divide was increasing. The need to commit 24/7 to one’s employer stressed some. Crises hit agriculture – Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), foot and mouth disease in sheep. Our multi-ethnic society was increasingly apparent. Racially motivated riots (Oldham), protests against a global economy, and violence in the streets, sometimes black-on-black and against NHS staff, soured the atmosphere. The fashion for body-piercing and cropped tops changed the townscape, while pressure led to the establishment of smoke-free public places. To the profit of pharmacies, a gullible public spent increasingly on ineffective ‘alternative’ medicines, while a split in the anti-vivisection movement led to terror tactics. For the young, adventure holidays and gap years proliferated, with a rising use of recreational and synthetic drugs and clubbing. Some died as a result. Institutional and financial malpractice, threats to the pension schemes and banks (Northern Rock) accompanied financial crisis.

In 1998, Labour devolved power to an elected Parliament in Scotland and an elected assembly in Wales and Northern Ireland. Four different health services emerged. In England there was an accent on the purchaser/provider split, improving performance and setting targets; in Scotland a professionally led integrated system based on clinical networks; and in Wales, partnership between the NHS and local authorities. Both in Scotland and Wales, benefits were available for the care for the elderly, drug availability and in prescription charges that were not in England. The differences in funding under the Barnett formula were apparent.

Public spending as 2007–2008

|

% of GDP |

Total expenditure per head |

|

|

England |

41.1 |

£7,121 |

|

Scotland |

50.3 |

£8,623 |

|

Wales |

57.4 |

£8,139 |

|

Northern Ireland |

62.7 |

£9,385 |

Source Sunday Times, 9 March 2008

Towards a new model of NHS

In no previous decade had such a succession of Ministers, new policies, White Papers and restructurings hit the NHS. It seemed that, great though clinical advances were, the NHS was overshadowed by structural change, hospital scandals and an increasing desire to legislate and regulate deep-seated problems away. With ever-increasing speed, the pieces on the NHS chess board were moved around. Health advisors in No 10, economists, and operational research staff now played a role in shaping policies, largely accepting Virginia Bottomley’s concept of a tax-funded and largely free service but one in which provision was not necessarily in the public sector. A raft of policies emerged; not always compatible, seldom evidence-based; private sector involvement, quality, peer review, central direction, performance reporting, accountability, competition, trusts, patient choice, and payment by results.2 There was bipartisan support for many policies, such as the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), a purchaser/provider split, Foundation Trusts, concentration on long-term illnesses, patient choice, involving primary care in commissioning, a tariff system to pay providers and a more personal service. Both Parties looked at what could be learned from managed care organisations such as Kaiser Permanente whose characteristics included integration of funding with provision of service, integration of inpatient care with outpatient care and health promotion, focus on minimising hospital stays by emphasising prevention, early and swift interventions based on agreed protocols, and highly co-ordinated services outside the hospital; teaching patients how to care for themselves, emphasis on skilled nursing, and the patients’ ability to leave for another system if care was unsatisfactory. Kaiser did NOT have a purchaser/provider split.

In each decade there are concepts affecting the organisational pattern of the NHS. In the 1970s, it was consensus management. In the 1980s, the general management function. Now, spurred by scandals in the financial sector and industry, good governance became a guiding principle. In 1992, the Cadbury Report had identified principles of good governance in organisations – integrity, openness and accountability. This was taken further in the Nolan Report (1997) and absorbed into NHS management.

The private sector and the NHS

There was an increasing role for the private sector as the NHS moved from a services provider to a commissioning organisation. This was opposed by Frank Dobson (at one time Secretary of State), substantial parts of the Labour Party, unions, NHS management and sometimes the medical profession. Previously used by the NHS as a pressure release valve, the private sector was becoming integral to all segments of the NHS. Commercial organisations tendered and supplied family practitioner services, hospital trusts increasingly contracted out services, and patients might have a choice of a private hospital. The private finance initiative funded hospital building, and privately managed independent treatment centres handled NHS patients. DHL took over the supply and transport of hospital supplies. Perhaps it was not surprising that the NHS decided to brand itself. In 1999, to imply focus and consistency of service, Frank Dobson told the NHS to adopt a single logo.

Yet the UK spent less than almost any other Western country on private health care. The number of those in the UK with private medical insurance had remained static for several years but increased again in 2000 to 5 million, about 12.6% of the population. More were insured in the south than the north and some used fixed cost ‘pay-as you go’ packages. Cataract removal for £2,000, knee replacement for £7,000 or a heart bypass for £10,000 might be a practical proposition.

Ethics and patient participation

Ethical problems abounded, particularly in genetic medicine and in-vitro fertilisation. Parliament considered issues such as the creation of ‘rescue babies’ whose stem cells could help a sibling. The General Medical Council (GMC) issued advice on consent and ethical problems; doctors must set aside their religious and other personal beliefs if these compromised the care of patients. Community Health Councils (CHCs) were replaced by the Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health in 2003, itself abolished in 2008 and replaced. Foundation Trusts provided members with other opportunities to participate.

Health service information systems and Internet

It was the decade of Google, Yahoo, Facebook, YouTube, Wikipedia, Blogs and Amazon. Apple gained market share; Microsoft stumbled. In 1998, 6 million in the UK had access to the web at home or at work and, within the decade, the majority had broadband access. The clinical knowledge on the web was so vast that doctors might find useful suggestions by using Google.

The US Government, the Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente were early in the field. The UK was initially cautious but, by 2000, the NHS, the Department of Health and the British Medical Association had effective websites and increasingly used them to publish their documents and reports. The NHS website was re-launched as NHS Choices in June 2007 to provide patients, carers and the public with accurate and up-to-date health information.

Education benefited. The National Electronic Health Library, a resource primarily for professionals, was followed by the National Library for Health. In 1998 the British Medical Journal (BMJ) became an open access journal, making the full text freely available. In 2003, the BMJ Publishing Group provided access to the evidence-based summaries available in Clinical Evidence. Journals increasingly offered online editions, sometimes free, and Stanford University’s Hire-Wire Press hosted several hundred electronic versions of scientific journals and provided a search system. The US National Library of Medicine’s free digital archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature – PubMed Central (PMC) – aimed to digitise a complete archive of medical journals, including the BMJ, some going back more than 125 years.

An effective NHS information system centred on clinical need was at last under development. Appropriate technology was becoming available. In 2002 the Audit Commission stressed the importance of accuracy in Data Remember: Improving the quality of patient-based information in the NHS.3 The assessment of the quality of care, and contracts that required information about who had done what for whom, and new services such as pharmacist prescribing and walk-in centres made a coherent IT system essential. An NHS Information Authority was established to manage the development of systems and oversaw the introduction of the NHS number, new numbers for babies, payments for GPs and national screening programmes. The strategy for NHS IT dated back to 1992, but recurrent problems reduced support for the programme. In 1998, a White Paper, Information for Health, created new momentum and shifted the emphasis to the clinical from the administrative.4 It committed the NHS to provide lifelong electronic health records for everyone with round-the-clock, online access to patient records and information about best clinical practice for all NHS clinicians. Every GP would be connected by 2000 – targets that were missed.

Further impetus followed a seminar in Downing Street in February 2002 and the Wanless Report in April 2002 which criticised NHS IT as “piecemeal and poorly integrated”. In July 2002, Delivering 21st century IT support for the NHS was published.5 An unprecedented investment began, some £18 billion over ten years. It was the world’s largest and most ambitious health programme, aiming to create comprehensive electronic health records to be made available to all providers.

Richard Granger was appointed National Director in 2002. Contracts stressed speed, competition and payment to contractors only if they delivered. In 2004, the Department of Health created a new body to deliver the programme renamed ’NHS Connecting for Health’. The programme was handled in a top-down fashion and was organised in two parts: a national spine; and five local providers covering five regional clusters. There was a habit of placing very large contracts, often outsourced. In retrospect, this hindered innovation and flexibility as issues changed, including the patterns of NHS organisation. In 2004, BT was awarded the contract to provide the national infrastructure and to be one of four Local Service Providers (LSPs). Three other firms won contracts to provide services in other areas. LSPs were responsible for IT systems such as GP and trust systems and would make sure local applications could share information with the national systems.

National contracts were also awarded to BT for the NHS Care Records Service, Atos Origin (formerly SchlumbergerSema) for Choose and Book, and BT for the New National Network. BT would act as a system integrator and BT Syntegra for information and payments under the Quality and Outcomes Framework. The system involved:

- A national network for the NHS – fast connections to all NHS sites, and an electronic referral service, ‘Choose and Book’, so patients could choose which hospital they would like to attend at a time to suit them, exercising choice. The programme fell two years behind, but by 2007/08 the system was increasingly reliable.

- There was also the NHS Care Records Service (NHS CRS) containing basic patient information and health details so people would be able to access their record and all their health information and be involved in making decisions about their own care and treatment. As a spin-off, data for research would be available. This fell grossly behind schedule.

- Electronic prescription service (EPS) – to enable prescriptions to be sent from the GP to the dispenser and then for reimbursement.

- Picture archiving and communications system (PACS) – an unexpected and rapid success that allowed X-rays and scans to be stored and transmitted electronically, completed in 2007.

- The National Electronic Library for Health (later Health Information Resources) designed with the NHS employee, doctor or nurse in mind.

The programme limped along and many hospitals had to upgrade ageing systems. GPs could continue to choose one of a range of existing systems as a national standard one was not available. Suppliers faced major losses and gave up contracts. Public anxiety about the security of personal information was increased by a series of alleged security breaches. Richard Granger left the programme in 2007, by which time the NHS spine was in place, covering basic data, name, address and NHS number, but the summary medical record and its transmission between providers remained far off. A Department review found failures at the top; no one seemed to ‘own’ the big picture on information, there was no system to translate policy into business requirements, and a shifting of responsibility for IT around the Department.

However, by 1996, 96% of general practices were computerised and about 15% ran ‘paperless’ consultations. In hospitals, computing was treated as a management overhead and doctors had few incentives to become involved. For 20 or more years GPs had used PCs; hospitals needed larger machines. The differing structure of patient records from specialty to specialty and security all made for problems.6

In 1995/96 a new NHS number was issued to all patients on GPs’ lists. These numbers were the basis or electronic patient medical records. By 2001, it provided online access to over 60 million records.

Health Service Policy

The decade saw an unparalleled level of change, organisational, clinical and financial. The ‘New Labour’ model of the internal market saw Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) selectively contracting with providers. There were several ‘reviews of the NHS’ and the succession of ‘reforms’, ‘modernisation’ and ‘reorganisation’ hardly bears repeating but included:

- dismantling GP fundholding and establishing practice-based commissioning

- abolishing district authorities and forming primary health care groups, then turning them into trusts, and later merging them into half the number

- demolishing regional health authorities to create 28 strategic health authorities and then merging these into ten authorities

- creation of Foundation Trusts

- the Darzi reforms.

Until the 1990s, the NHS tended to the paternalistic, with limited choice for patients. Public spending had been controlled firmly, NHS waiting lists had risen, and Kenneth Clarke and Alain Enthoven aimed for an internal market to improve allocation of resources. Purchasing and provision were separated and the aim was to give patients more choice of provider and the information to make that choice. Initially purchasers continued to enter into large bulk contracts, the accent being on activity rather than outcome. With temporary hesitations, these principles were adopted by Labour, which added a fourth element in 2003 – a better payment mechanism.

The complexity of these changes, often differing from place to place, presents a messy story hard to present coherently. Finance was initially tight, then much more money became available, and as the decade ended worldwide financial crises loomed. A plethora of policies, many individually sound, seemed to have been developed without regard to each other, did not always mesh together and produced unanticipated results. Each of the five Secretaries of State imposed (with the support of Downing Street, Tony Blair or Gordon Brown) his or her own approaches, so there were u-turns – for example, on private health care.

Frank Dobson (1997–1999). Apart from the elimination of fundholding, and the substitution of ‘commissioning’ for ‘contracting’, there was little change. Labour’s ten-year agenda was set out in the The New NHS - Modern, Dependable,7 and, during Dobson’s watch, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), a health inspectorate and national service frameworks were established.

Frank Dobson (1997–1999). Apart from the elimination of fundholding, and the substitution of ‘commissioning’ for ‘contracting’, there was little change. Labour’s ten-year agenda was set out in the The New NHS - Modern, Dependable,7 and, during Dobson’s watch, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), a health inspectorate and national service frameworks were established.

Alan Milburn (1999–2003) arrived “as the wheels were coming off” as a result of a financial crisis. Labour had assumed that, if it reversed Tory reforms and Alan Milburn smothered hospitals with affection, all would be fine. It now discovered that many Conservative reforms had merit. Milburn and his successors developed and refined the Conservative reforms, with a new and sometimes disruptive dynamism and a desire for massive change across a broad front, epitomised by his NHS Plan (2000)8. Other key documents were Shifting the Balance of Power (2001)9, Delivering the NHS Plan (2002)10 and The Wanless Report.

Alan Milburn (1999–2003) arrived “as the wheels were coming off” as a result of a financial crisis. Labour had assumed that, if it reversed Tory reforms and Alan Milburn smothered hospitals with affection, all would be fine. It now discovered that many Conservative reforms had merit. Milburn and his successors developed and refined the Conservative reforms, with a new and sometimes disruptive dynamism and a desire for massive change across a broad front, epitomised by his NHS Plan (2000)8. Other key documents were Shifting the Balance of Power (2001)9, Delivering the NHS Plan (2002)10 and The Wanless Report.

There was central command and control, although with some attempt at devolution; small increases in funding were replaced by major additions projected over many years. Milburn recognised that the NHS was underfunded and obtained more money to expand staff training and recruitment, an increase of 250,000 over the next six years. There was a start of a major building programme of hospitals under the Private Finance Initiative. Radical changes in organisation and funding took place. The idea of Foundation Hospitals was born, and Labour sought partnership with private health care to create new capacity and to provide a challenge to complacency in the NHS. It looked to the experience of other countries such as the USA.

Simon Stevens, the health advisor to the prime minister from 2001–2004, and the intellectual force behind many of Labour’s reforms, wrote that the attempt to increase capacity, improve quality and increase responsiveness while avoiding cost inflation was based on three parallel strategies.

- Supporting providers by increasing their number, modernising infrastructure, supporting learning and the improvement of the system. (Capacity would be increased through staff recruitment, public-private partnership projects and new providers.)

- Improving efficiency and reducing variation in performance by setting standards (cost effectiveness, tariffs, contracts, National Service Frameworks, inspection, regulation, publishing performance information and direct intervention when necessary).

- Using market incentives for change and local accountability (for example, patient focus and choice, star ratings, reforming financial flows, competition and commissioning).

John Reid (2003–2005) was deeply committed to Bevan’s vision of a national health service, but he eased the rapid pace set by Alan Milburn. He focused more narrowly on a few key things that might be delivered. At last there were improvements in waiting lists and staffing. Foundation Hospitals were a divisive issue, but Reid continued to develop them. GPs and consultants fought against new contracts and then accepted them, gaining far more money than the Department had predicted. Reid established a review of the many ‘arm’s-length bodies’ and continued the ‘modernisation’ policies of his predecessor, placing increasing emphasis on patient choice. The new market of financial flows (Payment by Results) came into effect, and there was increasing emphasis on chronic diseases and long-term care. Key documents were A patient led NHS: Delivering the NHS improvement plan11

Patricia Hewitt (2005–2007) continued these policies with progressive introduction of private sector services, moving to a more market-based approach. Her major initiative was the White Paper in 2006: Our Health, Our Care, Our Say - Community Care 12 on shifting care from hospitals to the community services.

Patricia Hewitt (2005–2007) continued these policies with progressive introduction of private sector services, moving to a more market-based approach. Her major initiative was the White Paper in 2006: Our Health, Our Care, Our Say - Community Care 12 on shifting care from hospitals to the community services.

Alan Johnson, (2007–2009) a former union general secretary appointed by Gordon Brown, took a fresh look. As part of his Government of All Talents (GOATS) Gordon Brown selected a high-profile surgeon, Professor Lord Darzi. Johnson was particularly committed to the reduction of health inequalities and published a review of the progress and next steps in reducing them. Yet another review of the NHS explored “the causes of dissatisfaction among staff and patients”. High quality care for all 13was published in June 2008.

Alan Johnson, (2007–2009) a former union general secretary appointed by Gordon Brown, took a fresh look. As part of his Government of All Talents (GOATS) Gordon Brown selected a high-profile surgeon, Professor Lord Darzi. Johnson was particularly committed to the reduction of health inequalities and published a review of the progress and next steps in reducing them. Yet another review of the NHS explored “the causes of dissatisfaction among staff and patients”. High quality care for all 13was published in June 2008.

The Incremental Policy Developments 1998–2007

The New NHS – Modern, Dependable

When Labour came to power in 1997, Frank Dobson (and his Minister Alan Milburn) found to their dismay that, while in opposition, the party had developed no health service policy ready for implementation. They were starting from scratch. In December, Labour issued The New NHS – Modern, Dependable,14 their initial vision, conceding that some of the features of the Conservatives’ internal market were worth keeping, while denouncing many. The government wanted to get things done fast and without necessarily relying on local management bodies. Watch-dogs, systems of audit, targets, and external and retrospective methods of control proliferated, as did ‘zones’, initiatives and ‘tzars’ with a responsibility for improving specific service.

The New NHS built on: current trends; better communication within the service; GP out-of-hours services increasingly using nurses to assess emergency calls; NHS Direct – the new nurse-led help line; and an accent on quality with new national supervisory bodies. Labour established a National Institute for Clinical Excellence – now the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) – to investigate and approve cost-effective pharmaceuticals and interventions for use in the NHS, and a Commission for Health Improvement (CHI) (later the Healthcare Commission) to see what was, in fact, happening.

The harder edges of the internal market were softened. Fundholding would go, co-operation replacing more extreme forms of competition. ’Partnership’ and ‘integration’ would replace the internal market. The jargon changed to that of New Labour; ‘seamless services’ became ‘joined-up thinking’. National guidance stressed the interdependence of health and social care, a return to the attempts by Barbara Castle and David Owen in 1974 to integrate health and social services planning. The NHS Act (1998) gave legislative authority for these changes and also the basis of professional self-regulation of the General Medical Council.

Main features:

- New services for patients including a 24-hour, nurse-led help line

- Connect every hospital and surgery to NHSnet

- NICE and Commission for Health Improvement to issue guidelines and oversee clinical quality locally

- Replace the internal market with ‘integration’

- Statutory duties of partnership to be placed on NHS bodies

- 500 primary care groups of GPs (later Trusts) to take control of most of the NHS budget subsuming fundholding.

The run-up to the NHS Plan

By autumn 1999 it was clear that the NHS needed a lot more money urgently. A Mori poll showed that public satisfaction with the NHS fell substantially between 1998 and 2000 from 72% to 58%. Alan Milburn, becoming Secretary of State, reversed one of Frank Dobson’s policies and encouraged co-operation with the private sector. Following a ’Panorama’ interview with Tony Blair on 16 January 2000, extra money was found for the NHS in the March 2000 budget, on condition that the service and the professions ‘modernised’ themselves. Burdens on GPs might be reduced by NHS Direct and walk-in clinics; GPs, dentists, opticians, pharmacists and physiotherapists might group to take on more hospital work; and old people might move out of big hospitals to convalesce in smaller ones. The extra money – a higher growth rate of some 7–9 per cent – was generous.

In May 2000, the government issued millions of questionnaires and established six service reviews. Richard Branson of Virgin Airways was to advise on how to make hospitals more consumer-friendly. While he and his team made a number of suggestions about abysmal patient care, they went well beyond their remit, concluding that the NHS was being undermined by poor management and promoting an increase in the use of private companies. The report suggested short stay specialist elective units, GP “poly-clinics” and extended into areas of regional pay, consultant contracts and staff salaries, elements that would later find their way into Labour’s NHS Plan.

A seminal analysis had been published in 1999 by Professor Alain Enthoven, who had earlier assisted thinking about the NHS in the mid-eighties. Enthoven analysed the 1991 reforms.15 He saw advantages in the competition and innovation and thought there had been a slight rise in productivity, although there had been higher ‘transaction costs’. Fundholding tilted the balance of power from secondary to primary care and in some trusts improvements had resulted from increased locally responsibility for performance. However, the information about costs and quality was often not available and incentives were sometimes perverse, with patients following the money allocated contractually, instead of money following patients to the hospital where they wished or needed to be treated. He argued for far greater attention to continuous quality improvement in the NHS. Could Labour make the NHS more responsive without introducing consumer choice, competition and needing substantially more money? Fundamental reform and examination of performance variation was required. He cautioned against ‘quick fixes’ and Labour’s tendency to centralise management and policy-making. He argued that consumer choice – to which the Conservatives had been moving – was essential. Labour was listening.

The NHS Plan

Labour’s second proposals for the NHS were issued in July 2000 – the NHS Plan16 set out to achieve a diagnosis of the problems, for example,. honesty about underfunding, an identification of priorities ( increasing capacity, improving responsiveness and dealing with major killing diseases), mechanisms to achieve change and a broad coalition of interested parties. Tony Blair MP, speaking to a meeting of the New Health Network Clinician Forum on Tuesday 18 April 2006 said:

We would first build up capacity and introduce new pay and conditions for staff and set strong central targets for improvement. However, the idea was then, over time, to move to a radically different type of service, abandoning the old monolithic NHS and replacing it with one devolved and decentralised with far greater power in the hands of the patient. The idea was and is to make reform self-sustaining; so that instead of relying on the necessarily crude and blunt instruments of centralised performance management and targets, there is fundamental structural change with incentives for the system and those that work within it, to respond to changing patient demand.

Labour consulted the public and the professions, the latter becoming became deeply and often enthusiastically involved. The doctors said that any plan had to be long term, if only because of the time it took to train staff. They could understand the political need for short-term fixes but this should not detract from the longer view. The British Medical Association (BMA) liked the government’s acceptance that the NHS was underfunded and there were too few doctors and nurses. Of more than 100 proposals, only one was unacceptable to the BMA in principle (debarring young consultants from private practice) and only a handful were questioned, (for example, that the staffing problems of the NHS might be solved at the expense of the Third World). The public wanted quicker access to a GP, an end to ‘trolley waits’ in A&E, booking systems for appointments and treatment, shorter waits for inpatient surgery and better food in cleaner wards. The Times believed that it was a coherent strategy, focusing on enhancing the numbers and function of nurses, addressing the role played by consultants, and increasing the number of beds that had fallen remorselessly for two decades. There were details and targets aplenty. Initiatives varied from “bringing back matron”, to the improvement of hospital food by consulting celebrity chefs. There would be guaranteed access to an Accident Department consultation within 4 hours, and a telephone and TV beside every hospital bed. Patients would not have to wait more than three months to see a specialist, or more than a further six months to have an operation. Central pressure was exerted on local management to meet waiting-time targets. The BMJ was similarly enthusiastic saying that “this is as good as it gets – make the most of it.”17

Main features of The NHS Plan

- More doctors, nurses and medical students by 2004

- Consultants to commit their first seven years to the NHS

- 7,000 more beds and 100 new hospital schemes by 2010

- All patients to see a GP within 48 hours by 2004

- Booking systems to replace waiting lists (later called “choose and book”)

- A patient advocacy service for each trust, replacing CHCs

- A UK council to co-ordinate the profession’s regulatory bodies (a reaction to perceived failures of the GMC after problems with heart surgery in Bristol and a determined attack on professional self-regulation)

- A new level of PCT to provide closer integration of health and social services.

The NHS Plan’s aspirations were not costed and, in the event, the same money was spent on several different things storing up a future crisis, for example, pay awards above inflation and poorly negotiated contracts, reducing the hours worked by junior doctors, the recommendations of NICE, the costs of National Service Frameworks for mental illness, cancer and heart disease and the costs of establishing PCTs. The NHS Plan raised expectations to an unsustainable level. Alan Maynard, professor of health economics at York, said it contained lots of words and good intent, but that the pearls among the manure had to be teased out. Even with enhanced budgets, the new agenda could not be afforded.

In spite of initial cynicism, patient waiting times declined, partly the result of trusts buying extra capacity by paying their consultants a premium rate to handle additional cases in the evenings or weekends. There was an assumption that there would be cash enough or, at least if government was rough enough with the NHS and its management, aspirations would somehow be delivered. Few Trusts had any chance of achieving all the targets and put finance at the top of their priorities. Chief executives might be warned that it would be ‘personally dangerous’ to make a fuss. The biggest threat to the Plan’s objectives was shortage of skilled staff. In some hospitals, the staffing level on wards was at crisis point and patients were not even being washed. David Hunter wrote that the evidence from successive reorganisations since 1974 was that altering the structure and configuration of health authorities invariably resulted in unrealistic expectations, for changing the culture of an organisation required stability, costs higher than forecast with a loss of irreplaceable skills and expertise, and failure to save money. Managers were unhappy, not because of the government’s goals, or its diagnosis of the problems of the NHS, but because of the way policy was implemented, the obsession with organisational restructuring, micro-management, short-term demands, ‘must do’ edicts, and a name and shame culture. Alan Milburn drove the high-profile and politically important Plan. In a series of documents, he set out his vision of a health service; who provided the service became less important than the service provided. Within a framework of common standards, subject to common independent inspection, power would be devolved to allow local freedom to innovate and improve services. Hospitals earning more autonomy would be subject to less monitoring and inspection, have easier access to capital, and be able to establish joint venture companies.

Legislation

The changes in The NHS Plan and Shifting the balance of Power within the NHS required legislation because of the alterations to the nature and duties of health authorities. Patient advisory and liaison services (PALS) would be established to provide assistance to patients, resolving problems where possible, but helping patients when a formal complaint seemed appropriate. In September 2001, the government established a Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health. The impetus owed much to Professor Sir Ian Kennedy who had chaired the Bristol report into heart surgery (2001)18. The Commission had the responsibility for establishing, funding, staffing and managing a network to take over the function of the CHCs. It was a complex structure and in 2004, when ‘arm’s-length bodies’ were reviewed, the Commission’s future was questioned. It was closed in March 2008 to be replaced by Local Involvement Networks (LINks) coterminous with local authorities.

Key Points of Legislation enacted as National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Act 2002:19

- Wider role and more independence for CHI

- CHCs axed: hospital-based PALS, patients’ forums and a national Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health

- Council for the Regulation of Healthcare Professionals

- Strategic Health authorities to be set up; old health authority powers devolved to PCTs

- Changes to prison service health care.

Delivering the NHS Plan (April 2002)

After the 2002 budget had increased funding, Alan Milburn, published Delivering the NHS Plan – next steps on investment, next steps on reform.20 This introduced important new ideas such as a change in the pattern of financial flows in the NHS moving to payment by results (PbR) using a tariff system. Health Resource Groups would establish a standard tariff on a regional basis for the same treatment regardless of provider.

- Foundation Hospital Trusts would be identified. They would be established as independent public interest companies, outside Whitehall control, and governed only by performance contracts and inspection by the Healthcare Commission. They would have greater freedom of decision-making.

- Patient choice would be encouraged. Patients would be given information on alternative providers and would be able to switch hospitals to have shorter waits. Patients who had waited more than six months would be offered services at an alternative hospital.

- PCTs would be free to purchase care from the most appropriate provider, public, private or voluntary.

- A new Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (CHAI) – this Healthcare Commission would be created by legislation, taking over the responsibilities of CHI, health audit responsibilities of the Audit Commission and the National Care Standards Commission, a body concerned with the private sector that had only been in operation for three week.

The wheel had turned full circle within a decade and was returning to something like the Conservatives’ market reforms. Alain Enthoven described the plan as a bold wide-open market, more radical than the previous Tory version of an internal market system. Kenneth Clarke agreed that it was the internal market re-written and oriented to patient choice and devolution. Clarke’s reforms had faced a barrage of criticism from medical organisations; now there was little protest.

Modernisation and the Modernisation Agency

Modernisation became the mantra. Many of its concepts had a transatlantic origin, and the new NHS Modernisation Agency worked on projects with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston. Changes in skills mix, including the use of nurses for triage and to replace medical staff, reflected the development in the USA of nurse practitioners in the 1980s. Treatment centres were similar to US ambulatory care centres. Health Resource Groups were akin to Diagnostic Related Groups. Even national service frameworks owed much to the US guideline and health care pathway movement. The enthusiasm of those outside government who had been involved in the NHS Plan’s construction was channelled into the Modernisation Agency and its taskforces to encourage transformation, change, improvement and innovation. Doctors might be antagonistic, partly because of the fear of the increasing power of management, and the acceptance that all clinical decisions had resource consequences. There was a need to balance clinical decisions with accountability and accept the power-sharing implications of teamwork.21

The NHS Modernisation Board included several Trust chief executives, a professor of surgery (Professor Ara Darzi), a senior nurse, and board members of the Alzheimer’s Society, the Citizens Advice Bureaux and the Commission for Racial Equality. The Modernisation Agency – part of the Department of Health – was established to drive change and grew like Topsy, attracting quality staff from trusts and authorities. It was about performance improvement. The Agency became involved in helping failing trusts, running some 60 different programmes. By 2004 it employed 760 people and had a budget of £230 million, but the Department decided to reign it in. Lessons were distilled into ten high-impact changes.22 For example, trusts should treat day surgery as the norm for elective surgery and avoid unnecessary follow-ups. The bulk of its work was devolved and the Modernisation Agency was closed in 2005, parts being integrated into a new NHS Institute for Improvement and Innovation.

The NHS Improvement Plan

In 2004, John Reid published the NHS Improvement Plan,23 four years after the publication of the NHS Plan itself. This stressed the importance of the care of chronic diseases and of public health. It described a vision for the future of patient choice of provider, a reduction in waiting times to a maximum of 18 weeks by 2008, maximum wait of eight weeks for referral to treatment for cancer patients by 2005, and delivering more care, more quickly through investment and reform, offering people more personalised care and a greater degree of choice, and greater concentration on prevention rather than cure.

Labour had not traditionally favoured choice in public services, although Alan Milburn had felt patient choice important and the ability of people to choose where they might be treated, and how, might improve the system.24 In December 2003, the government published a strategy paper Building on the Best: Choice, Responsiveness and Equity in the NHS.25

From autumn 2004, patients waiting more than six months for elective surgery were offered the choice of faster treatment in alternative hospitals. Some PCTs established referral management centres to influence and control patient referrals, predominantly those by GPs, either directly or indirectly, and to manage demand so that it stayed within financial limits. In general such schemes saved little money and might delay or reduce the quality of patient care. The alternative providers were often in the independent sector or new independent treatment centres or trusts with spare capacity. A Patient-led NHS, published in March 2005, allowed independent providers such as BUPA to be included on the list of choices. But if money flowed into private hospitals, there was a substantial threat to the budget of NHS ones. Competition was being encouraged.

Arm’s-length bodies

In October 2003, John Reid decided to review NHS arm’s-length bodies to save £500 million in staff costs. The number had risen substantially since the ‘Quango hunt’ of the 1980s (review of the quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations). Education and training, regulation, and service/back office functions, were handled by 42 bodies employing ten times the number in the slimmed-down Department of Health. In July 2004, the results of the review were published; some bodies were to be abolished (for example, the Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health, only established a year or so previously.) Others to be combined, (for example, the National Clinical Assessment Authority with the National Patient Safety Agency; and the Health Development Agency with the National Institute for Clinical Excellence).

Structural reorganisation (2002) ‘Devolution Day’ – 1 April 2002

Structural change was continuous. New organisations were formed, functions were redistributed, and soon they might be merged with others or abolished. The New NHS – Modern, Dependable began this process. The eight regional offices of the Department of Health’s Management Executive, said to be central to the system, were made redundant.

GP fund-holding was replaced by other methods of giving primary care influence over the hospital sector, Primary Care Groups and later PCTs. Like a pack of cards, other organisations had to change to fit in. As PCTs were given control over expenditure, the function of Health Authorities diminished and they were abolished. The organisational structure unwound until change affected every level – from the GP to the Secretary of State. Mr Milburn said that the NHS seemed top heavy, with the NHS Executive, eight regional offices, 99 health authorities and confused lines of reporting. Power would move to the front line.

The regional offices were reduced in number to four, as part of the Department of Health, and co-located with other government regional functions. The Health and Social Care Act (2001) allowed the Secretary of State to permit companies to provide services formerly provided by the NHS, and to employ doctors, nurses and other clinical staff. It also made possible a new form of Trust – Care Trusts – to provide closer integration of health and social services. Broadening the range of options for the delivery of integrated care, they could levy charges, in particular for ‘personal care’. Four new care trusts, in Northumberland, Bradford, Manchester and Camden & Islington, united mental health trusts and social care, but few were created.

On Devolution Day, major structural change took place. Some 20,000 people were affected as authorities merged, disappeared or were re-formed. Responsibilities were reallocated and the absence of clear guidance gave an impression of making things up as one went along.

The Department of Health

From 1985, when the Department of Health accepted the Griffiths Letter and created a management cadre within the NHS, it changed its own structure, dividing into an NHS Management Executive, while ‘wider’ departmental functions – for example, international health – remained within the remit of the Permanent Secretary. Increasingly, the Management Executive was staffed by people with managerial skills from the NHS or outside it, as opposed to career civil servants. The relocation of the Management Executive to Leeds in 1992/93 increased this, and progressively the running of the NHS came to seem the most important function of the Department – and one requiring great and continuing political influence.26In 2000, the top jobs of permanent secretary and chief executive of the NHS Executive were re-combined. The Department was now far smaller than previously, focused on delivering political objectives, and perhaps weaker on policy research capacity. The latter role would frequently be filled by political advisers, often brilliant but with a particular agenda. Rudolf Klein wrote that, “As of May 2006, only one of the top 32 officials in the DH [Department of Health] was a career civil servant, whereas 18 came from the NHS and six from the private sector. The shift has been from those who saw their role as being to save ministers from themselves, to those who saw it as being to deliver results. If the pathology of the former approach was conservative obstructionism, that of the latter was a readiness to run with even the silliest ministerial initiative.”27 The Department would set strategic direction, distribute resources and determine standards, ensure integrity of the system through information systems, staff training and support for development, develop values for the NHS through education, training and policy development, and secure accountability for funding and performance, including reports to Parliament.

Four new regional Directorates of Health and Social Care (DsHSCs) replaced the eight regional offices. The directorates – North, South, Midlands and East, and London – did not map the boundaries of the previous eight regional offices and, when they had only been in existence for nine months, the Department of Health reviewed functions to shrink its staff and move jobs away from London. Regional directorates disappeared, their work was redistributed to the 28 special health authorities (SHAs) or to new organisations, such as CHAI and the Health Protection Agency, that were being established.

Strategic health authorities (SHAs)

28 SHAs were created, taking some of the work of the erstwhile Regional Offices. They would “develop a coherent strategic framework. agree annual performance agreements and performance management agreements, build capacity and support performance improvement.”

They also replaced the 96 remaining Health Authorities and managed the local NHS translating national policy into local strategy. The CEOs were, as a group, board brush rather than detail people – charismatic, networking, political, and with a clear view of what they wished to achieve. They constructed plans, annual performance and delivery agreements and were not involved in operational management or revenue allocations. They shifted from being part of the provider system to regulation, to ensure that the recommendations of bodies such as CHI were acted upon. They ‘performance managed’ PCTs and NHS Trusts through local accountability agreements and prioritised major capital plans. SHAs related to between five and 19 PCTs. In London there were five SHAs, not unlike the inner parts of the old Regional Health Authorities (for the shire counties had been removed) reflecting the five-sector scheme of Turnberg.

SHAs – 2002

|

Avon, Gloucestershire and Wiltshire |

Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire |

|

Birmingham and the Black Country |

Cheshire and Merseyside |

|

County Durham and Tees Valley |

Coventry, Warwickshire, Herefordshire and Worcestershire |

|

Cumbria and Lancashire |

Essex |

|

Greater Manchester |

Hampshire and Isle of Wight |

|

Kent and Medway |

Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland |

|

Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire |

North and East Yorkshire and Northern Lincolnshire |

|

North Central London |

North East London |

|

North West London |

Northumberland, Tyne and Wear |

|

Shropshire and Staffordshire |

Somerset and Dorset |

|

South East London |

South West London |

|

South West Peninsula |

South Yorkshire |

|

Surrey and Sussex |

Thames Valley |

|

Trent |

West Yorkshire |

SHAs could associate to discharge functions better fulfilled together. The five London SHAs did so, dividing certain responsibilities – for example, children’s services, or the Ambulance service – between themselves.

Primary Care Groups and Trusts

The management of primary care had changed little over the years. Now there were radical and progressive alterations. Confusingly named as ‘Primary Care’ they had expanding responsibilities that spread into commissioning most hospital care. Labour had abolished fundholding, making the formation of primary care groups a centrepiece of its reforms. The knock-on effect on the rest of the NHS structure was only slowly appreciated. Money was increasingly disbursed through primary care groups and trusts. Only a minority of NHS managers had experience in primary care – most had gravitated to the hospital service. In April 1999, Family Health Services Authorities (FHSAs) disappeared, 481 Primary Care Groups (PCGs) were established in England, and fundholding ended.

GPs were brought organisationally together with community nurses within PCGs to integrate GPs, community health and social services. PCGs were a step for GPs into a corporate world. They had complex functions, including the provision and commissioning of care, and a lead role in improving health, reducing inequalities, managing a unified budget for the health care of their registered populations, improving quality, and integrating services through closer partnerships.

PCGs ran for a while in parallel with their health authorities while evolving, often by merger, to become PCTs with wider clinical and financial functions. The number of health authorities fell, driven by a progressive reduction in their responsibility for commissioning services. By 2002, there were 302 PCTs, each covering populations averaging about 170,000. Most PCT boundaries were set with coterminosity in mind, matching the boundaries with those of local authorities. In London there was always a match with local authority boundaries.

The advantages of being big – managing risk and economies of scale – clashed with the advantages of being small, adaptable to local needs, and being close to primary care. As Trusts grew bigger, their discussions were increasingly concerned with broad planning issues (for example, the commissioning of complex supra-regional hospital services), and less in details of individual practices and patients. PCTs were very expensive organisations and many merged for this reduced the transaction costs of contracting. When the first chief executives were recruited, there was no knowledge of the major role expansion about to happen – responsibility for the bulk of NHS funding. In April 2003, allocations were made directly to PCTs and the health authorities were wrapped into SHAs.

Four elements were used to set PCTs’ actual allocations:

- weighted capitation targets – a formula based on the age distribution of the population, additional need and unavoidable geographical variations in the cost of providing services

- recurrent baselines – representing the actual current allocation that PCTs receive

- Distance from target

- Pace of change policy – the speed of change was decided by Ministers for each allocation round.

PCTs placed an emphasis on planning. Service Level Agreements were succeeded by Joint Specific Needs Assessments on the basis of which contracting was organised. They had to answer the questions “What did an area need? What did the PCT want to buy? And what was available locally?” PCTs had to develop new and commercial commissioning skills, and it was important for the PCTs to work with providers, wherever possible, to ensure that nobody had a nasty surprise. No more than 10% of services were commissioned regionally or nationally (because they were highly specialised), and GPs were involved through practice-based commissioning, in which they had the right to advise the PCT on the services required. In 2006 it was announced that the number of PCTs would be reduced to 152 from October that year, making them larger and more strategic in nature, saving money and potentially strengthening their commissioning functions.

NHS Trusts

Hospital trusts were least affected by devolution day. Their lines of accountability changed repeatedly as the organisations around them shifted their functions, to regional offices and later to SHAs for their statutory duties, and to health authorities and later PCTs for the services they delivered. The number of Trusts fell through merger; 22 Trusts merged in 1998, and a further 49 in 1999.

NHS Foundation Trusts

The concept of Foundation Trusts is said to have emerged in 2001 when Alan Milburn visited a Madrid hospital that was freed from detailed bureaucratic control and able to borrow money from big banks, rather than using funds under tight public control. Two central ideas were: a new form of social ownership with services owned by and accountable to local people rather than to central government; and decentralisation and devolution. The concept was trialled in a speech to the New Health Network in January 2002, and several Trusts expressed an interest in piloting the proposals. In July 2002, acute hospital trusts were told they could apply to be Foundation Trusts. Legislation was necessary and details appeared in December in the circular The Guide to NHS Foundation Trusts.28 Each Trust would have a board of governors representing the interests of patients, staff, local partner organisations, local authorities and the local community. The Secretary of State for Health would not have the power to direct, nor be involved in appointing their board members. The Trust’s management board would be accountable to the governors, who would elect the chair and non-executive directors. It was a complex model – perhaps over complex – and not entirely to the liking of some managers. They had greater financial and managerial autonomy, including freedom to retain surplus finances, to invest in delivery of new services, and the flexibility to manage and reward their staff.

The idea split the Labour Party. Some MPs feared that foundation status would fragment the NHS and create a two-tier system in which the best hospitals could get more cash and poach staff, that it would denationalise the NHS and allow back-door privatisation. All parties had objections and Trusts’ freedom was progressively constrained. Their borrowing would be on the government’s balance sheet, and pay and conditions of service would be within The Agenda for Change, a national personnel policy. They would be accountable (through contracts) to PCTs. There would be an independent regulator (Monitor) to supervise them and decide what services should be provided and, if necessary, dissolve Trusts. There would be safeguards to prevent the sale of hospitals or their assets, and limit the extent to which Foundation Trusts could undertake private practice – a huge problem for some hospitals such as Great Ormond Street that had a massive international practice. Nevertheless, Foundation Trusts would be able to redevelop and re-equip themselves more easily and carry over surplus money year on year.

In March 2003, the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Bill was introduced. John Reid took the Bill through the House and many Labour MPs voted against it, and it was the votes of Scottish MPs, whose constituencies were unaffected by the legislation, which saved the government when the Bill first passed the Commons in July 2003. It was passed acrimoniously from the Commons to the Lords and back again. Foundation Trusts remained divisive. To the proponents, they would set the NHS free from the yoke of central government. To opponents, they were a back-door privatisation that would destabilise the NHS and introduce a two-tier service. Some claimed that they were in the teeth of Bevan’s vision for the NHS and destroyed concepts of equity and universality. Others believed that a varying quality of service from place to place was inevitable within such an immense health care system, that patient choice was required, and that more freedom encouraged development and improvement of the NHS to the benefit of all. The Bill eventually passed in November 2003.

NHS Foundation Trusts differed from existing NHS Trusts in three key ways: the freedom to decide at a local level how to meet their obligations; a constitution that made them accountable to local people, who could become members and governors; and authorisation, monitoring and regulation by Monitor. The Council of Governors, separate from the board of directors, was chaired by the Trust chair. Governors were elected by staff, patients and the public, along with representatives from the local PCT, (university) and local authority. Not responsible for the day-to-day management of the organisation, budgets, pay or other operational matters, they appointed the chair and non-executive directors and determined their pay.

Monitor, an independent regulatory body, was appointed under the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003 to assess, authorise and regulate Foundation Trusts. Chaired by Bill Moyes, previously the Director-General of the British Retail Consortium, it considered applicants. One of the first Foundation Trusts, Bradford Teaching Hospitals, moved rapidly into a large and unpredicted deficit. Monitor called in auditors and replaced the chairman and management team. Subsequent waves were delayed to ensure that PbR was taken into account. Monitor introduced systems of assessing Foundation Trust performance, their governance, the provision of mandatory services and financial performance.

The first wave of ten Trusts authorised on 1 April 2004

|

Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals |

Bradford Teaching Hospitals |

|

Countess of Chester |

Doncaster and Bassetlaw Hospitals |

|

Homerton University Hospital |

Moorfields Eye Hospital |

|

Peterborough and Stamford Hospitals |

Royal Devon and Exeter |

|

Royal Devon and Exeter |

The Royal Marsden |

|

Stockport |

In July 2005, the Healthcare Commission submitted its report on the first 20 Trusts. They had: increased the ability to plan and develop new services and relate to their local populations; used their financial freedoms for capital investment and improved services, for example, offering specialist services in the community; increased local public and patient involvement through governor membership; and maintained standards of care in terms of access to and quality of care and positive relationships with local commissioners and other local providers. They had not destabilised local health services by using unfair competition to attract staff; nor ‘cherry picked’ patients who were easier to treat; had continued to invest in staff education and training; and mostly worked in partnership with other NHS services and organisations in the local health community. By the 60th anniversary of the NHS in 2008, there were 103 Foundation Trusts. Some were adopting stratagems to increase their critical mass by associating with other hospitals, or, in the case of specialised Trusts such as Moorfields (eyes) and the Marsden (cancer), developing satellite units off-site. Mental health trusts, in particular, used their new freedoms to good effect.

Our Health, Our Care, Our Say

Published by Patricia Hewitt in January 2006, Our Health, Our Care, Our Say29 proposed a shift of resources from hospitals into the community. Community hospitals in areas of high population – perhaps with a different functional content and a range of clinical specialties – would be encouraged. Major hospital development should be reviewed, and 5 per cent of health resources should be shifted from hospital to community services over the next ten years. The White Paper envisaged bringing some specialties from the hospital nearer to people, for example, dermatology, ear, nose and throat (ENT), orthopaedics and gynaecology, and encouraging community hospitals that provide diagnostics, minor surgery, outpatient facilities and access to social services in one location.

A progress report in October 2006 discussed demonstration projects, GPs who were trained surgeons operating on hernias in upgraded surgery facilities, specialist nurses from hospital following up women who had been discharged early after mastectomy, and GPs with specialist interest seeing outpatients in place of consultants. The projects were worthwhile, but many required investment in premises or staff training, and did not seem likely to revolutionise health care or save much money.

Structural reorganisation 2006

Labour’s election manifesto in 2005 made a commitment to reduce management costs in the NHS by £250 million. This required a reduction in the number of organisations. Following the election, a further wave of organisational change began: Creating a Patient-led NHS 30 had promised to move money from management to the front line. There would be a reduction in the number of SHAs, PCTs and Ambulance Trusts. In December 2005, Patricia Hewitt published Healthcare Reform in England: Update and Next Steps31 and, in April 2006, announced a reduction of SHAs to ten. Coterminosity with Government Office of the Regions’ boundaries was almost complete. The role of the new SHAs, established in July 2006, was to develop plans for improving health services in their local area, make sure local health services were of a high quality and were performing well, increase the capacity of local health services – so they could provide more services and make sure national priorities (for example, programmes for improving cancer services) were integrated into local health service plans.

The Strategic Health Authorities, July 2006

|

East Midlands |

South Central |

|

East of England |

South East Coast |

|

London |

South West |

|

North East |

West Midlands |

|

North West |

Yorkshire and Humber |

SHAs consulted on the reduction of the number of PCTs to cut management costs and the new PCTs were established from 1 October 2006.

Source: Audit Commission 2008 – Is the Treatment Working?32

The Darzi developments

Professor Ara Darzi had worked at the Central Middlesex Hospital in the 1990s when it was developing a groundbreaking ambulatory care unit and had joined the NHS Modernisation Board. He was used as a flying ambassador to look at local health problems, became chair of the London Modernisation Committee and a trusted adviser on health issues to Labour. He was knighted in 2002 for services to medicine. In 2006, Sir Ara was asked by David Nicholson, Chief Executive of the NHS London (the London SHA) to review services, which appeared as A Framework for Action.33 One of its fundamental proposals was the establishment of polyclinics to integrate primary care, support services and specialist outpatient services. Wishing to involve clinicians, he hand-picked many for clinical working groups and received support both from the SHA and the management consultants, McKinsey’s.

Around the time he became Prime Minister in June 2007, Gordon Brown attended a presentation on health issues by Ara Darzi, and when Brown selected his Ministers, Darzi was one of the GOATS, outside people to take part in a “government of all talents”, and became a life peer in the House of Lords. His influence increased rapidly and it was rumoured he had the PM’s mobile phone number. His views and reports came to influence health service policy, hospital system restructuring and issues of quality. Darzi, a clinician, was driven by quality. He said: “I believe what I would like to be said is that I focused our minds on what matters most, with quality being the organising principle of any health care system. It is quality that wakes me up in the morning to come to work; it is quality that my patients expect from me.”

Lord Darzi of Denham took charge of a national review established by Alan Johnson when Secretary of State. The timescale was rapid – less than a year. Many SHAs were already reviewing their services. In October 2007, when a snap election was being discussed, Lord Darzi published an interim report setting out a ten-year vision, Our NHS, Our Future.34 Its principles should be:

- Fairness – equally available to all, taking full account of personal circumstances and diversity

- Personalised service – tailored to the needs and wants of each individual, especially the most vulnerable and those in greatest need, providing access to services at the time and place of their choice

- Effectiveness – focused on delivering outcomes for patients that are among the best in the world

- Safety – an NHS as safe as it possibly can be, giving patients and the public the confidence they need in the care they receive.

Darzi proposed a new distribution of services in primary and hospital care, including polyclinics, local hospitals, major acute hospitals, elective centres, specialist hospitals and academic health science centres. NHS London, the London SHA, established an agency, Healthcare for London, that consulted on the Darzi report and the London PCTs accepted its thrust. To allay misgivings, Darzi published a report, Leading Local Change35 that said that change would always be for patients’ benefit, clinically driven, locally led, subject to local comment, and that existing services would not be withdrawn until better ones were available. Nevertheless, there was the impetus, at least in London, to push polyclinics forward amid increasing controversy. Most seemed likely to be upgrades of units already in existence. Darzi’s work on London began to have national repercussions as he moved into government.

A NHS University

Labour’s 2001 election manifesto pledged to create an NHS University to assist in-house education and training of all staff. There was some hostility from existing educational bodies; medical schools and nursing departments had no wish to lose students to such an organisation. Established in December 2003 as a special health authority, it never developed a clear role. In December 2004, it was announced that it would merge with segments of the Modernisation Agency and the NHS Leadership Centre as an NHS Institute for Improvement and Innovation, assuming a role in the implementation and delivery of change in the NHS, and was established in 2005 as an England-only Special Health Authority, located in the campus at the University of Warwick.

Research strategy

Britain might be falling behind in research and its translation into clinical practice, inthe face of major centres in the USA, the west coast and Boston, let alone China and other countries. Imperial College, with its vast educational and clinical resources, planned the establishment of a biomedical research centre (BRC). In 2006/07 the Hammersmith Hospitals NHS Trust and St Mary’s NHS Trust integrated with Imperial College London, creating Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, the UK’s largest.

Following the report of the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology (Chair Lord Walton), a review by Sir David Cooksey (2006) and one by Professor Anthony Culyer in 1997 on UK health care research, all NHS Research and Development budgets were brought into a single funding stream. Professor Dame Sally Davies, the Department of Health’s Director of Research and Development and Chief Scientific Adviser, consulted on how a research strategy should be implemented within the NHS. Best Research for Best Health,36the government strategy published in January 2006, set the goals for research and development over five years and commitment to “creating a vibrant research environment that contributes to the health and wealth of England.” They were to improve the nation’s health and increase the nation’s wealth and develop a research system that focuses on quality, transparency and value for money.

The report was followed by the establishment of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and a move to a more open funding system, including international assessment of biomedical research centres to be supported at a national level. A panel of international experts chose centres in open competition as internationally excellent in research. In December 2006, the Secretary of State announced the selection of five comprehensive Biomedical Research Centres to be supported on a national basis – three in London (Kings, UCL and Imperial) plus Oxford and Cambridge, and a further six in particular clinical fields. UCL with Great Ormond Street, Moorfields Eye Hospital, The Royal Free and University College London Hospitals came together as UCL Partners. In London, selection as a centre was a guarantee that restructuring of the service would take research excellence into consideration.

Independence for the NHS?

Should the NHS have more independence from government? The clinching argument had always been that, as the NHS was funded almost entirely from taxpayers’ money, parliamentary accountability was essential. Tony Blair believed that independence would have major disadvantages, but others demurred, including the King’s Fund and the BMA. The Conservatives also called for an independent board to run the NHS and extension of the freedom of Foundation Trusts. A report for Nuffield37 outlined options – for example, a modernised NHS Executive within the Department of Health to separate policy from delivery, a commissioning authority, modelled on the Higher Education Funding Council for England and operating as a non-departmental public body at arm’s length from ministers or a corporation – a fully managed national service on the BBC model comprising all publicly owned assets, including Foundation Trusts.

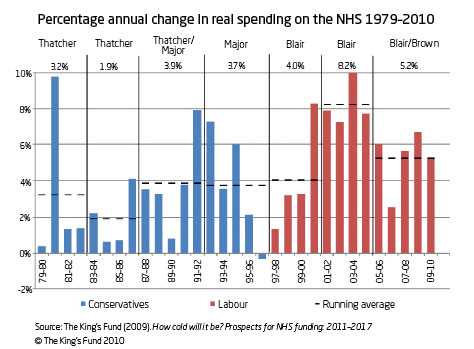

Finance

Parliamentary briefing – NHS Funding and Expenditure

Financial problems became a central issue and theprime ministers, Tony Blair and his successor Gordon Brown, were deeply involved. How much money should come to the NHS and how was it best distributed? A more commercial framework was introduced, particularly in the case of Foundation Trusts. Financial tricks that had enabled authorities to conceal deficits, such as the transfer of capital to revenue, or borrowing money from other Trusts, ceased. The system became more transparent. 38 The funds for the health service are the result of annual or bi-annual negotiation between the Department of Health and the Treasury. The NHS was pressured by pay rises, the pay structure of all NHS staff which was being ‘modernised’, new patterns of service, (for example, out-of-hours cover in primary care that raised costs), and a shortage of nurses and doctors because too few had been trained, making it hard to use additional money effectively. Capacity bought in from the private sector was at a high cost – costs of drugs and medical technology for NICE’s recommendations – creating an additional pressure, as was the rising mean age of the population.